ARCHIVE

Vol. 2, No. 1

JANUARY-JUNE, 2012

Research Articles

Research Notes and Statistics

Special Essay

Field Reports

Book Reviews

Debt of Rural Households in India:

A Note on the All-India Debt and Investment Survey

Pallavi Chavan*

This note critically evaluates the conceptual framework and sampling methodology of the All-India Debt and Investment Survey (AIDIS), the most important source of secondary data on the debt, assets, and savings of rural and urban households in India.

The note is organised in four sections. The first section provides some general information about the AIDIS. The second section discusses changes introduced in the sampling methodology of the AIDIS across different survey rounds. The third section examines the effects of these changes on the AIDIS estimates. The last section provides some concluding observations.

All-India Debt and Investment Survey: An Introduction

The All-India Debt and Investment Survey (AIDIS) is a sample survey that generates basic quantitative information on the assets, liabilities, and capital expenditure of the household sector in the economy. The AIDIS provides data on household debt by credit agency (formal and informal sectors), purpose (production- and consumption-related loans), interest rates, and security/collateral. It divides debt into two categories: cash debt (including loans on hire purchase) or debt taken in cash, irrespective of whether it is settled in cash or kind; and debt taken in kind, irrespective of whether it is settled in cash or kind. All the estimates of the AIDIS are based on cash debt. Debt in kind, along with dues payable to various agencies such as shopkeepers and schools, are termed as “current liabilities” and are classified separately.1

The AIDIS also provides data on the assets of households. Household assets include physical assets (such as land, buildings, livestock, farm and non-farm equipment, and durable household assets) and financial assets (such as shares, deposits, and loan receivables). They do not include crops standing in fields and stocks of commodities held by households. From the 1991–92 round onwards, cash held by households on the date of the survey was also included under financial assets. Thus it is perhaps more appropriate to refer to financial assets as “stock of financial savings” of households. The AIDIS values physical assets at their current market prices in their existing condition in the given locality.

Starting with the survey conducted in 1951–52 by the Reserve Bank of India (RBI), there have been six rounds of surveys in the AIDIS series till date. The first survey, called the All-India Rural Credit Survey (AIRCS), was designed primarily to provide a policy direction to the RBI on issues relating to rural credit. It not only collected data on the liabilities of rural households, but also undertook an extensive investigation of formal and informal credit agencies operating in rural areas. The next survey, conducted by the RBI in 1961–62, focussed on the assets and indebtedness of rural households. It was called the All-India Rural Debt and Investment Survey (AIRDIS).

The responsibility for studying the rural credit system in the country was statutorily assigned to the RBI (EPWRF 2006). This explains the RBI’s involvement in the AIRCS and AIRDIS. Section 54 of the RBI Act, 1934, stated that

the Bank may maintain expert staff to study various aspects of rural credit and development, and in particular it may –

(a) tender expert guidance and assistance to the National Bank;

(b) conduct special studies in such areas as it may consider necessary to do so for promoting integrated rural development.

However, on account of various “administrative and other attending problems” in conducting the AIRCS and AIRDIS, the RBI decided to hand over the responsibility of conducting the third round of the survey to the National Sample Survey Organisation (NSSO).

From this third round (1971–72) onwards, the coverage of the survey was extended to include urban households and it came to be called the All-India Debt and Investment Survey (AIDIS). Although the responsibility of conducting the survey was with the NSSO, the RBI contributed to the 1971–72 and 1981–82 rounds by pooling the Central and State samples.2 The RBI also contributed to the 1971–72 round by canvassing a separate RBI sample. From 1991–92, however, the survey results were based on the Central sample alone and the RBI ceased to play any role in the survey. There have been suggestions, since then, that the RBI should resume its contribution to the AIDIS. The Committee on Informal Financial Sector Statistics, for instance, suggested in 2001 that there should be “close collaboration” between the RBI and the NSSO in the organisation of the AIDIS.3

The results of the AIRDIS were made public within a relatively short period of time after completion of the survey, possibly because its coverage was limited to rural households (Table 1). Even the results of the AIRCS, which had a much wider scope, were published within two years of the survey. However, there was a lag of five to six years in the publication of results from the subsequent three rounds, conducted in 1971–72, 1981–82, and 1991–92. The results of the most recent round, of 2002–03, were again published within two years of the survey.

Table 1 AIDIS rounds, years of enquiry and publication of results

|

AIDIS rounds |

Year of publication of first report |

|

1951–52 |

1954 |

|

1961–62 |

1963 |

|

1971–72 |

1977 |

|

1981–82 |

1987 |

|

1991–92 |

1998 |

|

2002–03 |

2005 |

Source: Compiled by the author.

Issues Related to Sampling Methodology

There are two major issues that emerge with regard to changes in the sampling methodology of the AIDIS since 1961–62: a reduction in the sample size of villages and households, and an increase in the size of the State sample. These are discussed below.

Reduction of Sample Size

There was a sharp reduction in the sample size of villages and households during the 1981–82 and 1991–92 rounds of the survey (Table 2, columns 4 and 5). These were followed, however, by an increase in the sample size during the 2002–03 round.

Table 2 Number of sample villages and rural households, AIDIS, 1961–62 to 2002–03

|

Year of survey |

Central sample |

State sample |

RBI sample |

Total sample size of villages used for estimation |

Total sample size of rural households used for estimation |

Number of sampled households per sample village |

|

(1) |

(2) |

(3) |

(4) |

(5) |

(6) |

|

|

1961–62 |

1,889 |

168 |

- |

2,057 |

82,280 |

40 |

|

1971–72 |

4,548 |

3,910 |

3,994 |

12,452 |

1,49,424 |

12 |

|

1981–82 |

3,755 |

3,963 |

- |

7,718 |

61,744 |

8 |

|

1991–92 |

4,321 |

4,731 |

- |

4,321 |

36,425 |

9 |

|

2002–03 |

6,552 |

- |

- |

6,552 |

91,192 |

14 |

Source: RBI (1965, 1977a, 1987); NSSO (1998, 2006).

The decline in the sample size of households in 1981–82 and 1991–92 was because fewer households were selected per village during those rounds (Table 2, Column 6). Narayana (1988) has argued that, between 1961–62 and 1981–82, there was a shift towards sampling a larger number of villages and smaller number of households per village. However, this shift held true only between 1961–62 and 1971–72; in the 1981–82 round, there was a reduction in both the number of sampled villages and households. There was a similar reduction both in the number of sampled villages and households during the 1991–92 round as well; and this trend was reversed only during the 2002–03 round.

I shall now discuss the sampling procedure of the AIDIS in greater detail. For the 1961–62 survey, each State was divided into a number of strata that were roughly equal in size and with relatively homogeneous agricultural conditions.4 The sample of villages was allocated to each stratum in proportion to its population size, and the villages were selected at random with probability proportional to the population size in 1951 (RBI 1963). Forty households were then chosen randomly from each of these sample villages (ibid.).

For the next two rounds of the survey (1971–72 and 1981–82) the NSSO used a two-stage stratified sampling method, with villages constituting the first-stage units and households the second-stage units. The all-India sample of villages was allocated among various States on the basis of various considerations, such as their rural population, area under cereal crops, and investigator strength, but ensuring that at least 180 villages were sampled in each State (Narayana 1988).5 The first-stage units were selected circular systematically with equal probability. In 1981–82, the sample of villages was chosen with probability proportional to population and with replacement. In 1971–72 and 1981–82, the population size was measured as per the population figures provided by the Census of 1961 and 1971 respectively.

From 1971–72 onwards, for selection of the second-stage units, all households in a sample village were arranged in ascending order of “land possessed” (operated) and divided into four strata (RBI 1977a).6 Those possessing land less than 0.005 acre (0.002 hectare) were considered as non-cultivators and formed the first stratum. In 1971–72, three households were drawn from each stratum, making a total of 12 households from each sample village. In 1981–82, two households were drawn from each stratum, making a total of only eight households from each sample village. In other words, the sample size of households per village in 1981–82 was only one-fifth of the sample size in 1961–62.

Between 1981–82 and 1991–92, there was a minor increase in the number of households selected per village – from eight to nine. In 2002–03, the number of households per village was increased to 14. More importantly, in 1991–92 and 2002–03, households were selected by applying two criteria: “land possessed” and “indebtedness status” (NSSO 1998).7

Increase in the Size of the State Sample

The second point that emerges with regard to the sampling methodology of the AIDIS is that, over successive rounds, there was a substantial increase in the size of the State sample of villages (Table 2). The survey of 1961–62 was carried out by field staff of the RBI, but in certain States such as Punjab, Gujarat, Assam, Orissa, and Rajasthan, State statistical bureaus were also involved in covering the matching samples of the State. The total size of the State sample was lower than the sample covered by the RBI field staff (RBI 1963). Moreover, the results were based on a pooling of the two samples.

In 1971–72, the NSSO covered 4,548 villages in the Central sample, and different State agencies covered 3,910 villages in the State sample (RBI 1977b). There was also an additional matching sample or an RBI sample of 3,994 villages (RBI 1977b). The estimates were prepared after pooling these three samples. In 1981–82 and 1991–92, the size of the State sample exceeded the Central sample. As there was no pooling of Central and State samples during the 1991–92 round, and the survey results of this round were entirely based on a relatively small Central sample.

Reliability of Debt Estimates

A number of questions have been raised about the reliability of the estimates provided by the 1981–82 survey. Narayana (1988) found that the total sampling variance in 1981–82, inclusive of both within- and between-village variance, was much greater than the corresponding figures from the 1961–62 and 1971–72 rounds. This pointed to the possibility of an unreliable estimation of indebtedness during the 1981–82 survey.

According to Narayana (ibid.), the estimate of the incidence of indebtedness of households (percentage of indebted households) was likely to be particularly unreliable. The reason was that the reliability of any estimate generally depends upon whether it shares any linear relationship with the stratification variable. From 1971–72, the AIDIS had used “land possessed” as its stratification variable. Narayana argued that it was difficult to trace any direct relation between the area of land possessed and the incidence of indebtedness. In other words, the proportion of indebted households was not likely to be higher among households with a greater size of landholding. Therefore, the change in the sampling methodology could be expected to affect the reliability of the estimate of incidence of indebtedness.

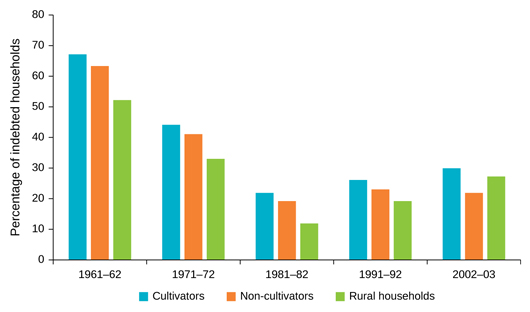

Narayana’s argument was supported by a study by Prabhu et al. (1988), which argued that there was a sharp reduction in the share of indebted cultivator households between 1971–72 and 1981–82 – a period that witnessed a significant expansion of credit from institutional sources. There were only 1,833 rural bank branches in 1969, and the number increased to 17,656 by 1981. As against this, there was a major fall in the incidence of indebtedness between 1971–72 and 1981–82 (Figure 1). According to Prabhu et al. (ibid.), the above paradox could be attributed largely to an underestimation of the incidence of indebtedness in 1981–82.8 From the low base of 1981–82, the incidence of indebtedness increased through the subsequent AIDIS rounds of 1991–92 and 2002–03 (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Incidence of indebtedness, rural households, AIDIS, 1961–62 to 2002–03 in per cent

Source: RBI (1977a, 1987); NSSO (1998, 2006).

Other studies have argued that the reliability of the AIDIS estimate of extent of indebtedness (average amount of debt) is also suspect. Gothoskar (1988) compared the supply-side estimates of the volume of debt outstanding (obtained from the records of cooperatives and commercial banks) with the demand-side estimates of the same (obtained from the AIDIS). He found an underestimation by the AIDIS of the volume of debt by about 50 per cent in 1981–82 and about 40 per cent in 1971–72.

Based on a quick test of 208 households in Maharashtra, the RBI compared the amount of debt from the AIDIS with the records of Primary Agricultural Credit Societies (PACS), and found under-reporting by the AIDIS ranging between 3 per cent and 37 per cent (RBI 1977b).

Some other studies have concluded that reduction in the sample sizes of villages and households was responsible for the underestimation of household debt by the AIDIS (Narayana 1988; Prabhu et al. 1988; Rao and Tripathi 2001).

Apart from the shift in the sampling methodology, an increase in the State sample relative to the Central sample was also considered to be a factor influencing the quality of the AIDIS data. Bell (1990) argued that State government agencies were likely to be less equipped in conducting surveys than the NSSO, and that it was therefore desirable to allot a larger Central sample to be canvassed by the NSSO. Gothoskar’s (1988) findings corroborated this point: he showed that the estimates obtained from the State sample were lower than those obtained from the Central sample across different States.

An Exercise to Test Reliability of Debt Estimates from 1991-92 and 2002-03 Rounds

I have attempted a small exercise to test the reliability of the AIDIS estimates of amount of debt in the 1991–92 and 2002–03 rounds. I have compared the AIDIS estimates on debt outstanding to commercial banks with the data from the Basic Statistical Returns (BSR) on bank credit outstanding from commercial banks. My study differs from Gothoskar’s study (1988). Gothoskar took the total credit outstanding from rural branches of commercial banks, while I have taken credit to only specific sections. I have left out the bank credit that goes to the cooperative sector, the public sector, the private corporate sector, joint sector undertakings, and foreign governments, as this may not go directly to households. Thus the comparison here is between the BSR data on credit outstanding reported by the rural branches of commercial banks and regional rural banks (RRBs) to individuals, proprietorship and partnership firms, joint families, and self-help groups, with the AIDIS data on debt outstanding of rural households from commercial banks.

My exercise shows that the AIDIS underestimated household debt by about 46 per cent and 35 per cent respectively in its 1991–92 and 2002–03 rounds (Table 3). If I had followed Gothoskar’s method, the magnitude of underestimation would have been even greater.

Table 3 Comparison

of AIDIS and BSR credit data on commercial banks, 1991 and 2002

in Rs lakh

|

Variable |

1991 |

2002 |

|

|

1 |

Debt outstanding of rural households from commercial banks as per the AIDIS |

7,48,510 |

27,30,960 |

|

2 |

Credit outstanding from rural branches of commercial banks as per the BSR |

18,59,897 |

66,68,190 |

|

3 |

Credit outstanding from rural branches of commercial banks to selected sections as per the BSR* |

13,94,923 |

42,00,960 |

|

4 |

Extent of underestimation (in per cent) [(3–1)/3] |

46 |

35 |

|

5 |

Extent of underestimation following Gothoskar’s method (in per cent) [(2–1)/2] |

60 |

59 |

Notes: * Selected sections include individuals, proprietorship and partnership firms, joint families, and self-help groups.

Source: NSSO (1998, 2006); RBI, Basic Statistical Returns of Scheduled Commercial Banks in India, various issues.

Such a comparison needs to be treated with caution, as the definition of “rural” in the Census is different from the one used in the BSR. In the BSR, credit from rural branches refers to credit from branches located at centres having a population of less than 10,000. The Census definition of rural areas uses not just population, but also population density and occupational structure as defining criteria. In other words, the definition of rural areas by the Census may be much broader, and therefore the extent of underestimation by the AIDIS may be even greater than what is presented in Table 3.9

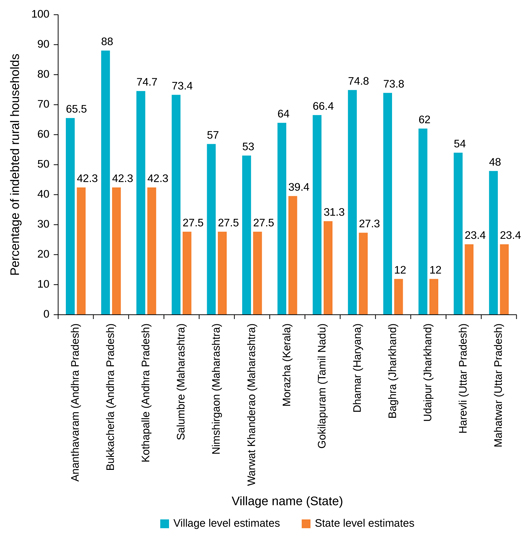

Another way to test the reliability of the AIDIS estimates is to compare them with estimates available from village surveys. In Figure 2, I have presented State-level estimates of incidence of household debt provided by the AIDIS of 2002–03 alongside estimates obtained from village surveys conducted by the Foundation for Agrarian Studies (FAS) in 2007 and 2008. This comparison is, of course, indicative.

The village surveys consistently showed a much higher incidence of indebtedness than the AIDIS. In 2002–03, State-level AIDIS estimates for incidence of debt rarely exceeded 40 per cent, and for most States were between 20 per cent and 30 per cent. On the contrary, the village surveys showed debt incidence ranging between 50 per cent and 75 per cent.

Figure 2 Incidence of indebtedness, AIDIS and village surveys in per cent

Source: Compiled from various FAS surveys and NSSO (2006).

Hence, even after an increase in the sample size, to an extent, the likelihood of underestimation of household debt during the 1991–92 and 2002–03 rounds cannot be ruled out. Therefore there is a need to re-examine the sampling methodology in general, and the sample size in particular, of the AIDIS. The Committee on Informal Financial Statistics (2001) has recommended an increase in the sample size of villages and households, as well as pooling of estimates from the Central and State samples, to improve the quality of the AIDIS estimates.

Though the AIDIS can be used to understand broad trends in rural credit over time, village surveys can provide useful insights into the rural credit system and can capture the magnitude of household debt more accurately.

Conclusions

The following are the major conclusions of this note:

- Data available on the incidence of rural indebtedness from the AIDIS, which is the most important secondary data source on rural credit, are significant underestimates owing to problems in the sampling methodology of the AIDIS.

- When AIDIS data on household debt were compared with data on credit outstanding from commercial banks, the extent of underestimation by the AIDIS was, by my computations, in the region of 46 per cent and 35 per cent respectively in the 1991–92 and 2002–03 rounds.

- State-level estimates of incidence of debt obtained from the AIDIS were consistently and substantially lower than the figures obtained from village surveys across various States.

- There is a need to re-examine the sampling methodology of the AIDIS in order to improve the accuracy of its estimates. This refers to both increasing the sample size, and pooling the Central and State samples of the AIDIS.

- Though secondary sources of large-scale data are important in providing broad trends in rural credit over time, intensive village surveys can play an important – and, indeed, essential – role in capturing the magnitude of household debt and diversity in household debt portfolios across space.

Keywords: AIDIS, rural credit, sample size, village surveys.

Acknowledgements: The author thanks V. K. Ramachandran, S. L. Shetty and R. Ramakumar for comments on an earlier draft of this note, and Niladri Sekhar Dhar and Partha Saha for processing data from village surveys conducted by the Foundation for Agrarian Studies for this note. A version of this note was presented at “Studying Village Economies in India: A Colloquium on Methodology,” held at Chalsa in December 2008. The author thanks the participants of the colloquium for useful comments. The views expressed in this note are those of the author and not of the organisation to which she belongs.

Notes

1 From the 1991–92 round onwards, AIDIS estimates of household debt have been based on cash debts. During the earlier rounds, debt in kind was included in estimating household debt. As a result, the figures on household debt from the 1991–92 round onwards are not strictly comparable with the corresponding figures from the earlier rounds. However, this difference is not expected to be significant, as debt in kind formed only about 1.5 to 2.5 per cent of total outstanding debt in the earlier rounds.

2 The Central sample was canvassed by the NSSO field staff and the State sample was canvassed by various State statistical bureaus.

3 See www.iibf.org.in for the Report of the Committee. The Report submitted by the Committee to the RBI in 2001 became a part of the Report of the National Statistical Commission.

4 A stratum is defined as a contiguous group of tehsils within a region with similar cropping pattern and geographical features (NSSO 1978). These strata are by and large of the same size, where size is measured in terms of population.

6 A similar criterion was employed earlier by the AIRCS. This was because the AIRCS regarded every household possessing/operating some land as an agricultural enterprise, and the operations of an agricultural enterprise were expected to provide an insight into credit requirements in rural areas (RBI 1956).

7 During the 1991–92 round, households were divided into four strata after arranging them in ascending order on the basis of size of land possessed, with the first stratum having households possessing no land or land less than 0.005 acre. The remaining three strata were constituted such that the total area of land possessed was almost equal in all three. In 2002–03, the formation of these three strata was modified as below:

|

Stratum |

Size-class of land possessed |

|

1 |

Land < 0.005 ha |

|

2 |

0.005 ha < Land< X |

|

3 |

X < Land < Y |

|

4 |

Y < Land |

where X and Y were the two cut-off points determined at the State level in such a way that 40 per cent of the households possessed land less than X, 40 per cent possessed land between X and Y, and 20 per cent possessed land greater than Y. Later, the first and second strata were each further divided into “indebted” and “not indebted”. The third and fourth strata were merged and classified into “indebted to institutional and non-institutional sources,” “indebted to non-institutional sources alone,” and “not indebted.” These, in total, gave rise to seven classes. From these, 1, 1, 1, 2, 1, 1, and 2 households were chosen respectively, making a total sample of nine households in the 1991–92 round (ibid.). During 2002–03, two households were chosen from each of these seven classes, making a total of 14 households.

8 See also Rao and Tripathi (2001) for a further discussion on underestimation of the incidence of debt.

9 There are certain reasons for an underestimation of the data on debt collected directly from households, as compared to data collected from banks. First, given that debt is a sensitive issue, households may not reveal the exact extent of their debt and hence there is bound to be some underestimation. Secondly, there could be a problem of memory lapse among households. For instance, households may not be able to recall and describe the exact details of loans that have been taken in the past and were outstanding at the time of a survey. In the books of the banks, however, the debt charge is expected to be reflected accurately. Thirdly, any estimate of total debt outstanding requires a correct calculation of principal and interest outstanding. Unless the reporting household and investigator are very systematic, there is likely to be some bias – either upward or downward – in the estimation of debt outstanding.

References

| Bell, Clive (1990), “Interactions between Institutional and Informal Credit Agencies in Rural India,” World Bank Economic Review, vol. 4, no. 3, pp. 297–328. | |

| Economic and Political Weekly Research Foundation (2006), “All-India Debt and Investment Surveys – A Pragmatic Look,” available at http://www.epwrf.res.in | |

| Gothoskar, S. P. (1988), “On Some Estimates of Rural Indebtedness,” Reserve Bank of India Occasional Papers, vol. 9, no. 4, December, pp. 299–325. | |

| Narayana, D. (1988), A Note on the Reliability and Comparability of the Various Rounds of the AIRDIS and AIDIS, unpublished paper, Centre for Development Studies, Thiruvananthapuram. | |

| National Sample Survey Organisation (1978), Glossary of Technical Terms Used in National Sample Survey, New Delhi. | |

| National Sample Survey Organisation (1998), “Note on Household Assets and Liabilities as on 30.06.91: NSS 48th Round (Jan–Dec 1992),” Sarvekshana, vol. 22, no. 2, October–December. | |

| National Sample Survey Organisation (2006), Household Assets Holdings, Indebtedness, Current Borrowings and Repayments of Social Groups in India – Report No. 503, New Delhi. | |

| Prabhu, Seeta K., Nadkarni, Avadhoot, and Achuthan, C. V. (1988), “Rural Credit: Mystery of Missing Households,” Economic and Political Weekly, vol. 23, no. 50, 10 December, pp. 2642–2646. | |

| Rao, K. S. Ramachandra, and Tripathi, A. K. (2001), “Indebtedness of Households: Changing Characteristics,” Economic and Political Weekly, 12 May, pp. 1617–1626. | |

| Reserve Bank of India (1956), All India Rural Credit Survey –The Survey Report (Part III: Rural Families) Volume I, Mumbai. | |

| Reserve Bank of India (1963), “All India Rural Debt and Investment Survey 1961–62,” Reserve Bank of India Bulletin, vol. 17, no. 12, December. | |

| Reserve Bank of India (1965), “All India Rural Debt and Investment Survey 1961–62,” Reserve Bank of India Bulletin, vol. 19, no. 9, September. | |

| Reserve Bank of India (1977a), All India Debt and Investment Survey – Cash Dues Outstanding against Rural Households as on 31st June, 1971, DESACS, Bombay. | |

| Reserve Bank of India (1977b), All India Debt and Investment Survey, 1971–72 – Indebtedness of Rural Households and Availability of Institutional Finance, Bombay. | |

| Reserve Bank of India (1987), All India Debt and Investment Survey 1981–82, Assets and Liabilities of Household as on 30th June 1981, DESACS, Bombay. |