ARCHIVE

Vol. 5, No. 2

JULY-DECEMBER, 2015

Research Articles

In Focus*

Review Articles

Tribute

Field Reports

Food Security in Brazil:

An Analysis of the Effects of the Bolsa Família Programme

Sabrina de

Cássia Mariano de Souza*, Niemeyer Almeida Filho†

and Henrique Dantas Neder‡

*Professor, Instituto Federal de Educação, Ciência e Tecnologia do Triângulo Mineiro

†‡Professor, Economics, Institute of the Universidade Federal de Uberlândia

Abstract: This

paper examines the impact of the Bolsa Família

Programme, an important anti-poverty policy in Brazil, on the food purchasing

power of low-income families. Microdata from the household-level Family Budget

Survey of 2008–9 are used to examine expenditure on different food items for

households below the poverty and extreme poverty cut-offs of the Bolsa Família Programme. We examined inflation

in food items that constituted the bulk of food expenditure of poor households

for the period 2000 to 2012, and found that domestic inflation followed

international price increases.

The data

presented in this paper suggest that while the programmes of the Lula

government represented significant political action towards combating hunger,

and led to major reductions in the number of poor and undernourished persons in

Brazil, the policies were insufficient to solve the problem of food

deprivation. Our estimates showed that even if all poor and extremely poor

families received the simulated benefits of the Bolsa Família Programme, this

would still not ensure access to the minimum food basket. Anti-poverty

programmes do not address issues of structural inflation, and in a period of

higher prices of foods, such as observed globally in recent years, access to

food can become critical.

Keywords: food inflation, food crisis, right to food, Bolsa Família Programme, Sao Paulo, Brazil, cash transfer, purchasing power, consumer basket, extreme poverty, poverty.

Introduction

The main cause of hunger, malnutrition, and food insecurity in Brazil is the lack of economic access to basic foods. This is a paradox, as Brazil has enormous potential for food production, much beyond the basic needs of its population. Access to food, however, is directly dependent on the market, at least in capitalist societies: on account of insufficient income, then, such access becomes difficult, resulting in undernutrition.

During the period 1996–8, on average, the undernourished population of Brazil comprised 10 per cent of the total population, or 15.9 million people.1 This figure accounted for 30 per cent of the undernourished population of Latin America, constituting the greatest absolute number of undernourished persons in the region (Belik 2003). These statistics led the FAO to assign Brazil to category three on a scale of one to five, where one is the least severe and five is the most severe in terms of the incidence of hunger. Brazil is thus characterised as a region of moderate to high incidence of hunger. According to the most recent data available, that is, for the period 2006–8, the place of Brazil in that classification remained the same, despite the fact that the number of undernourished persons fell to 11.7 million, or six per cent of the population (FAO 2011).

The reduction in the number of undernourished persons is a reflection of the change in government attitudes towards food security. Brazil is a pioneer in food security policy in Latin America.2 It is also the most advanced country in the region in terms of laws, institutions, and public awareness concerning the right to food (Vivero and Almeida Filho 2010). The improvements in undernourishment statistics arose from the Zero Hunger Programme implemented by the governments led by Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva (2003–11).3 One of the components of the Zero Hunger Programme, the Bolsa Família (Family Grant Programme), ensures a minimum income level to families vulnerable to food insecurity. According to data from the Ministry of Social Development and Combating Hunger (MDS), the resources allocated to income transfers, social protection, and food security have increased significantly in the 2000s. In 2002, R$8.5 billion (USD$4.3 billion) was spent on these programmes, a sum that went up to R$43 billion (USD$22 billion) in 2011. In 2010, allocations to Zero Hunger were R$19.5 ($9.9 billion) as compared to R$11.9 billion ($6 billion) in 2005 (Stangler 2011).

In 2010, there were 12.7 million families included in Bolsa Família, thus making it the largest income transfer programme in the world. The cost was R$14.37 billion ($7.3 billion), or 0.38 per cent of GDP. As a result, in 10 years, 26.1 million people were no longer in poverty. In 2000, there were 57 million people in poverty; this figure fell to 30.9 million by 2010 (Alves 2011).

Food security concerns have come to attract attention throughout the world after the recent increase in international food prices for items such as wheat, corn, rice, milk, meat, and soybeans — a period described as that of a “world food crisis.” A serious concern of policymakers and academics has been that the rise in inflation would erode the gains in income of the poorest sections of the population and, at least in the case of Brazil, lead to setbacks in the gains provided by increased employment, better salaries, and the other social policies of the Lula government (Ortega 2010).

As highlighted by the FAO (2009), the poorer a family is, the greater is the proportion of expenditure on food, and the greater the impact of higher prices on their purchasing power. Moreover, high food prices reduce the real income of poor groups in the short– and medium–term. Despite salaries being adjusted for inflation over time, empirical evidence shows that wage and salary changes usually either do not compensate for the full impact of increases in prices, or, if they do, are slow in responding to increases (Grosh, del Ninno, and Daniel, Tesliuc 2008).

Since 2003, increases in minimum real wages4 and the Bolsa Família have facilitated greater access to food. Greater control over inflation has also been a relevant factor.5 The mean annual inflation under the Lula governments up to 2009 was around 37 per cent less than the mean inflation under the eight years of the Fernando Henrique Cardoso (FHC) governments. In 2009, a minimum wage earning afforded the purchase of 2.2 consumer baskets,6 while in 2003, a minimum wage was only sufficient for 1.5 consumer baskets (DIEESE 2010).

The world food crisis has proven to be of a structural nature. According to a report from the World Bank (2008), the increase in prices of food items tends to persist in the medium term. The FAO’s own estimates suggest that domestic prices of food items have remained at relatively higher levels than those prior to the period of increase (Couto 2010), and various reports (FAO 2011, 2011a, 2012, 2012a) point to the rise in, and volatility of, prices as a long-term trend.

The world food crisis affected the Brazilian national inflation rate from 2007 onwards. In 2007, the rate of inflation of 4.46 per cent excluding the food component was 35 per cent less than the rate of inflation including the food component.7 Even so, Brazil is still a country in which the impact of the food crisis was dampened through successive record harvests and suitable public policies.

Considering all these elements, the purpose of this study is to assess food security in Brazil in the context of the world food crisis, with a focus on the impact of Bolsa Família, the main policy directed at confronting the problem. The hypothesis of this study is that the Bolsa Família Programme, although beneficial and effective, is not capable of resolving the problem of hunger in the country, because the causes of hunger and undernutrition are much deeper.

In the first section, we briefly present the role of Bolsa Família in the context of Brazilian food security policy as a whole. In the second section, we examine data from the Family Budget Survey (POF), classifying families by income ranges relevant to the cut-offs used as a criterion for selection of beneficiaries of the Bolsa Família Programme. The income classification used for Bolsa Família is based on the consumption profile of families: more specifically, it is based on per-capita household expenditure on food. The third section is a systematic analysis of variations in prices of food items that form the consumer basket from the beginning of the past decade, comparing them to the variations in the INPC (National Consumer Price Index), so as to see the effect of the global food crisis on Brazil.8 Finally, in the fourth section, we analyse the food purchasing power of the population at risk, in order to assess the potential impact of supplemental income from Bolsa Família on access to food.

In this paper, we define the term “food crisis” as a situation of dramatic reduction in access to food on account of rising commodity prices and reduced purchasing power in terms of a basic consumption basket for the population living in extreme poverty.

Bolsa Família and Zero Hunger: Contextualisation and Objectives

The Brazilian Government has an ambitious social policy programme to combat hunger. In a recent book, José Graziano da Silva wrote

Brazil is an international benchmark today when it comes to food security, rural development, and poverty eradication policies. This is so for three reasons. The first one is that eradicating hunger and fighting poverty have become key objectives on the domestic agenda. The fact that these objectives were included in the agenda as organising elements of Brazil’s macroeconomic policy is the second reason. And, finally, the third reason is that a national food and nutrition security policy and system have been created and consolidated based on a new legal and institutional framework and on a renewed set of public policies. (Silva et al. 2011, p. 9)9

Initially, social policy against hunger was identified with the Zero Hunger programme. José Graziano da Silva coordinated the design of the programme as a development programme in Lula’s campaign of 2002. Later, it was institutionalised as a federal programme comprising 30 different components.

Zero Hunger marked out the Workers’ Party (PT) government as socially progressive and seemingly more serious about dealing with poverty than any other previous regime. The programme itself was inspired by José Graziano da Silva, former professor of agrarian studies at the University of Campinas in São Paulo, appointed by Lula to head the newly created Ministry of Food Security and Fight Against Hunger. Zero Hunger was in practice an umbrella programme for initiatives already developed under the FHC (Cardoso) administration. These federal initiatives had in turn developed from localised projects started during the 1990s, replacing an earlier programme of distributing food parcels (cestas basicas — PRODEA)10 which operated from 1993 to 2000 and was designed to provide for the needs of a family for one month (Hall 2006, p. 694).

However, despite initial enthusiasm, the programme was heavily criticised for being ineffective. Many problems arose from the fact that each action or component of the programme operated independently of the other with no overall coordination. Each had separate administrative structures, beneficiary selection processes, and banking contracts for payment. The result was a focus on the most effective component, namely, Bolsa Família.

Overall, the Bolsa Família Programme has shown very good results. Data from the Ministry of Social Development (MDS) showed a significant reduction in poverty and income inequality in the 10 years since the implementation of the programme. Between 2001 and 2011, transfers from the federal government contributed about 15 to 20 per cent of the observed reduction in inequality of income, a significant factor in the context of Brazilian development (Campelo and Neri 2013, p. 18).

Nevertheless, there is a domestic debate about Bolsa Família with respect to two issues. The first is about the nature of the social policy itself, considering that it was created initially as a development programme. Bolsa Família was considered an emergency measure, but it later became a permanent, structural programme. The original Zero Hunger programme is still in operation. In terms of the budget, there has been a slight increase in resources allocated. The problem is that, within the Zero Hunger programme budget, there has been a comparative growth of resources allocated to the Bolsa Família Programme. For this reason, some analysts argue that the social policy has been converted or reduced to an income transfer policy.

The second issue concerns the effectiveness of the programme: there is a discussion about the potential of Bolsa Família to promote social transformation and fulfill its goals.

The official evaluation of the programme is favourable:

Over these ten years, a broad agenda of improvements was fulfilled. The result was an overlap of importance and emphasis on just one of them, that among all demonstrated greater effectiveness, the Bolsa Família Programme Thus, the programme was consolidated and became central to Brazilian social policy. At the international level, it is a reference in conditional cash transfer technology and is among the most effective actions to fight poverty.

The programme serves nearly 13.8 million households across the country, which is a quarter of the population. Featuring a solid instrument of socio-economic classification and a wide range of benefits, Bolsa Família operates in relieving immediate material needs, transferring income according to the different characteristics of each family. Additionally, on the understanding that poverty does not reflect only the deprivation of access to monetary income, Bolsa Família supports the development of the capacities of its beneficiaries by strengthening access to health services, education, and social assistance, as well as integration with a wide range of social programmes (Campelo and Neri 2013, p. 13).

Of course, we treat this debate as domestic because it has a direct political impact on elections. At the domestic level, the debate is more intense and widespread than at the international level.11

Consumption Profile Of Families In Poverty And Extreme Poverty

To assess the impact of the food crisis on the social condition of individuals, we consider the consumption profile in Brazil. The DIEESE (Inter-Trade Union Department of Statistics and Socio-Economic Studies) calculates the value of the national consumer basket. The starting point is an Executive Order or Decree-Law (Decreto Lei) no. 399 of April 30, 1938, which established that the minimum wage is “the remuneration owed to an adult worker, without regard to sex, for a normal day of work, capable of satisfying, in a determined time and region of the country, his normal needs for food, housing, clothing, hygiene, and transport.” The same Executive Order carries a list of food items, with their respective quantities, that constitute the “minimum consumer basket.” These foods would be sufficient for the sustenance and well-being of an adult worker, and would contain balanced quantities of proteins, calories, iron, calcium, and phosphorus (DIEESE 2012). In DIEESE’s definition and calculation of the price of the consumer basket, there are three alternative combinations of foods, so as to pick up regional differences in consumption.

In addition, there are studies of family budgets conducted by the IBGE (Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics). In this paper, we use unit data from the Consumer Expenditure Survey (POF) of 2008–9 (the POF methodology is explained in Appendix 1).12 The expenditure survey data were analysed using STATA software. First, in order to identify foods on which a high share of expenditure was incurred, the data on individual food items were catalogued and grouped. The final level of aggregation resulted in 68 food items. Although we have data on each product, at that level of disaggregation, considering that the survey lists more than 8000 food items, comparisons would be impossible. Expenditure on these broad food categories was examined in relation to the total value of consumption, for specific income intervals, for the country and the state of Sao Paulo.13

The income intervals used in this study were based, first of all, on the criteria used by the Bolsa Família Programme itself to identify individuals or households in conditions of poverty and extreme poverty, namely, a per capita income of up to R$140.00 and R$70.00, respectively. An income interval for individuals exclusively in poverty and not extreme poverty (that is, those having per capita monthly income in the range R$70 to R$140) was also used. In addition, income intervals used in the analysis of the data related to food in the PNAD (National Household Sample Survey) were used.

For the purpose of analysis, we focus on the 25 items out of the 68 under consideration that accounted for the greatest expenditure among all those with per capita household income less than R$140 (which is the upper limit for receiving benefits from the Bolsa Família Programme: see Tables 8 and 9).

In Table 1, at the national level, the 24 items that accounted for the largest part of expenses of persons with per capita household incomes of upto R$140.00 were also in large part the items that accounted for the largest part of expenses of those with per capita household incomes of up to R$70.00 (extreme poverty). Only the “soft drink” item was not part of the expenses of persons in extreme poverty. In addition, the 10 most important items of expenditure were the same for the two poverty groups, although the rank of items (in terms of share of total expenditure) differed across the two groups.

Table 1 Items of food, the share of expenditure on each item, and the rank of each item in total food expenditure, by per capita income range, 2008–9

| Item | Per capita household income range | ||||||||||||

| ≤R$70.00 | ≤R$140.00 | >R$70≤R$140 | >R$140≤half a minimum wage | >half a minimum wage≤one minimum wage | >one minimum wage | ||||||||

| % | Rank | % | Rank | % | Rank | % | Rank | % | Rank | % | Rank | ||

| Lunch and dinner* | 10.08 | 1 | 13.15 | 1 | 13.96 | 1 | 16.00 | 1 | 21.06 | 1 | 41.70 | 1 | |

| Rice | 8.20 | 2 | 7.06 | 2 | 6.77 | 2 | 6.00 | 3 | 4.66 | 3 | 2.11 | 9 | |

| Chicken | 7.03 | 3 | 6.59 | 3 | 6.48 | 3 | 6.13 | 2 | 4.90 | 2 | 2.63 | 3 | |

| Other meats | 4.97 | 4 | 4.39 | 4 | 4.24 | 5 | 4.38 | 4 | 3.89 | 4 | 2.38 | 5 | |

| Low-quality beef | 4.01 | 6 | 4.29 | 5 | 4.36 | 4 | 4.27 | 5 | 3.63 | 6 | 1.96 | 11 | |

| Beans | 4.33 | 5 | 4.08 | 6 | 4.02 | 6 | 3.51 | 7 | 2.65 | 10 | 1.17 | 23 | |

| Bread | 3.51 | 9 | 3.90 | 7 | 4.01 | 7 | 3.95 | 6 | 3.73 | 5 | 2.05 | 10 | |

| Fresh fish | 3.74 | 7 | 3.72 | 8 | 3.71 | 8 | 2.75 | 10 | 1.86 | 16 | 0.91 | 27 | |

| Processed meat and fish | 3.23 | 10 | 3.40 | 9 | 3.45 | 9 | 3.14 | 8 | 2.98 | 9 | 2.30 | 6 | |

| Other foods | 3.62 | 8 | 2.95 | 10 | 2.77 | 10 | 1.96 | 15 | 2.50 | 12 | 2.29 | 7 | |

| Crackers | 2.86 | 11 | 2.68 | 11 | 2.63 | 11 | 2.35 | 12 | 1.99 | 14 | 1.23 | 21 | |

| Other flours | 2.84 | 12 | 2.48 | 12 | 2.38 | 14 | 1.97 | 14 | 1.46 | 22 | 1.01 | 25 | |

| Cow’s milk | 2.39 | 15 | 2.46 | 13 | 2.48 | 12 | 2.94 | 9 | 3.13 | 8 | 2.23 | 8 | |

| Soybean oil | 2.81 | 13 | 2.38 | 14 | 2.26 | 16 | 1.95 | 16 | 1.56 | 19 | 0.75 | 30 | |

| Other sugars | 2.79 | 14 | 2.36 | 15 | 2.24 | 17 | 2.07 | 13 | 1.82 | 17 | 1.71 | 14 | |

| High-quality beef | 2.03 | 19 | 2.33 | 16 | 2.41 | 13 | 2.72 | 11 | 3.35 | 7 | 3.42 | 2 | |

| Manioc flour | 2.36 | 16 | 2.32 | 17 | 2.31 | 15 | 1.53 | 23 | 0.94 | 33 | 0.31 | 45 | |

| Ground coffee | 2.30 | 18 | 2.15 | 18 | 2.10 | 18 | 1.82 | 19 | 1.52 | 21 | 0.87 | 29 | |

| Powdered milk | 2.33 | 17 | 2.00 | 19 | 1.92 | 19 | 1.62 | 21 | 1.22 | 25 | 0.62 | 33 | |

| Pasta | 1.55 | 21 | 1.46 | 20 | 1.44 | 21 | 1.22 | 28 | 0.99 | 31 | 0.52 | 37 | |

| Other milk | 1.56 | 20 | 1.46 | 21 | 1.44 | 22 | 1.61 | 22 | 1.66 | 18 | 1.49 | 16 | |

| Beer, draught beer, and other drinks* | 1.18 | 24 | 1.40 | 22 | 1.46 | 20 | 1.85 | 18 | 2.14 | 13 | 1.73 | 13 | |

| Snacks | 1.20 | 23 | 1.39 | 23 | 1.44 | 23 | 1.88 | 17 | 2.59 | 11 | 2.58 | 4 | |

| Hen’s eggs | 1.53 | 22 | 1.38 | 24 | 1.34 | 25 | 1.24 | 25 | 1.05 | 29 | 0.58 | 35 | |

| Soft drinks | 1.07 | 27 | 1.33 | 25 | 1.40 | 24 | 1.68 | 20 | 1.95 | 15 | 1.74 | 12 | |

Notes: The first column for each income interval is the per cent of expenditure on an item as a proportion of total monetary expenditure on all food. The items marked with * refer to food consumption outside the home (POF4). The second column ranks foods in descending order of share of expenditure.

Source: Unit data from POF 2008–9.

Of the first 10 items, eight (excluding “lunch and dinner” — an item that refers to food consumption outside the home — and “other foods”)14 are elements of the national consumer basket. There is also a significant overlap with foods that comprise the consumer basket when the 25 items on which we focused are considered. For all the income groups, the “lunch and dinner” item was responsible for the greatest percentage of food expenditure, showing the current trend for consumption outside the home.

When the expenditure of those in the per capita household income interval greater than one minimum wage earning was analysed, seven of the products that made up the first 25 items of expenditure of those in the lowest income range no longer appeared in the list. In addition, as per capita income increased, the share of some products in food expenses fell. This was the case with hen’s eggs, which occupied the 22nd position in the lowest per capita household income group and moved to the 35th position in the group with earnings more than one minimum wage. The same was true for powdered milk, ground coffee, manioc flour, beans, pasta, and soybean oil.

The data presented in Table 1 show the change in the composition of food expenditure at different income levels. We cannot interpret these changes in terms of food security without examining the nutritional aspects of each food item. For those in the higher per-capita household income group, items such as “snacks” and “sandwiches and individual snack pastries” emerge as important, reflecting the greater possibility of choice in their consumption basket. As income levels rise, eating outside the home becomes an ever greater part of expenses.

Nevertheless, the most notable feature of the data is that the main items that make up expenses on food for families with income up to R$140.00, i.e., potential beneficiaries of the Bolsa Família Programme, coincide greatly with the foods listed in the consumer basket, both at the national level and for the city of São Paulo.

Effects of the Food Crisis on Prices

In this section, we analyse the evolution of the food crisis arising from inflation in foods that make up the group of items in the consumer basket. Although monitoring of prices of items in the consumer basket does not allow precise inferences regarding the degree to which the population has access to nutrition, the exercise allows us to estimate variations in such access (Lavinas 1998). The monitoring of prices of items in the consumer basket is useful because the consumer basket has been the standard diet in use for more than 70 years, and also because there is a systematic mechanism for monitoring. Changes in the consumer basket can be taken as a consistent and representative proxy for the evolution of purchasing power in the country for those at lower income levels. The foods contained in the consumer basket account for the greatest volume of Brazilian consumption within all the major food categories (cereals, tubers, foods that provide energy, carbohydrates and fats, fruit, and meats) and they exhibit low income-elasticity (Lavinas 1998).

Table 2 shows prices of items in the consumer basket between January 2000 and July 2012. As national values are not published by DIEESE, we have used data for the city of São Paulo. The cost of the consumer basket nearly tripled over the last 10 years. This increase was continuous, but occurred especially in 2008, a mark of the global food crisis. The cost of the consumer basket rose from R$186.98 in July 2007 to R$229.39 in July 2012. Important components of the price rise over this period were increases in the price of meat, from R$56.70 to R$74.64, and of beans, from R$13.46 to R$32.40. These are products that are among the main food expense items of lower income families, as seen in the data from the POF.

Table 2 Prices of selected products in the consumer basket for the city of São Paulo, January 2000 to July 2012 in R$

| Period | Meat | Milk | Beans | Rice | Flour | Potato | Tomato | Bread | Coffee | Banana | Sugar | Oil | Butter | Basket |

| January 2000 | 37.26 | 6.00 | 7.38 | 2.58 | 1.54 | 4.86 | 10.17 | 15.54 | 5.03 | 9.62 | 2.01 | 1.20 | 2.96 | 112.22 |

| July 2000 | 35.94 | 7.88 | 6.34 | 2.37 | 1.47 | 5.70 | 8.46 | 16.62 | 4.55 | 10.05 | 2.31 | 1.04 | 8.68 | 111.43 |

| January 2001 | 37.68 | 7.95 | 7.65 | 2.49 | 1.50 | 7.68 | 13.14 | 17.22 | 4.23 | 11.48 | 2.73 | 1.07 | 8.54 | 123.36 |

| July 2001 | 37.02 | 8.02 | 9.36 | 2.82 | 1.74 | 8.22 | 12.24 | 19.86 | 4.11 | 10.12 | 2.40 | 1.20 | 8.55 | 125.68 |

| January 2002 | 41.88 | 8.02 | 9.04 | 3.33 | 1.90 | 6.42 | 11.79 | 20.58 | 3.76 | 10.28 | 2.55 | 1.54 | 8.09 | 129.21 |

| July 2002 | 38.58 | 8.55 | 10.98 | 3.21 | 1.98 | 8.70 | 13.95 | 23.04 | 3.73 | 9.52 | 2.37 | 1.66 | 8.36 | 134.64 |

| January 2003 | 47.04 | 8.77 | 14.26 | 4.59 | 3.15 | 7.98 | 13.23 | 29.16 | 4.95 | 10.88 | 4.17 | 2.66 | 11.92 | 162.79 |

| July 2003 | 44.64 | 9.45 | 13.36 | 5.52 | 2.76 | 8.10 | 13.05 | 28.92 | 5.17 | 12.22 | 3.96 | 2.30 | 12.68 | 162.15 |

| January 2004 | 52.08 | 9.52 | 11.25 | 5.94 | 2.38 | 6.06 | 19.62 | 27.90 | 5.42 | 13.12 | 3.21 | 2.54 | 11.96 | 171.03 |

| July 2004 | 48.72 | 10.28 | 11.12 | 5.25 | 2.73 | 9.06 | 21.78 | 28.44 | 5.86 | 13.95 | 3.03 | 2.48 | 11.25 | 173.95 |

| January 2005 | 52.68 | 10.42 | 12.42 | 4.29 | 2.44 | 9.72 | 15.48 | 28.32 | 5.94 | 13.65 | 3.69 | 2.18 | 11.62 | 172.87 |

| July 2005 | 50.40 | 10.95 | 15.57 | 3.99 | 2.40 | 9.24 | 18.36 | 30.12 | 6.52 | 13.20 | 3.51 | 1.94 | 12.02 | 178.22 |

| January 2006 | 52.32 | 10.88 | 11.97 | 3.99 | 2.31 | 13.08 | 14.76 | 29.04 | 7.10 | 14.02 | 4.29 | 1.93 | 11.85 | 177.45 |

| July 2006 | 49.62 | 10.88 | 12.42 | 3.93 | 2.26 | 8.70 | 13.50 | 29.40 | 6.27 | 15.08 | 4.92 | 1.93 | 11.68 | 170.50 |

| January 2007 | 55.02 | 10.88 | 11.48 | 4.41 | 2.50 | 7.02 | 22.95 | 30.12 | 6.95 | 15.00 | 4.47 | 2.19 | 11.72 | 184.72 |

| July 2007 | 56.70 | 13.12 | 13.46 | 4.26 | 2.55 | 9.78 | 16.11 | 29.70 | 7.71 | 14.92 | 3.96 | 2.08 | 12.61 | 186.98 |

| January 2008 | 66.12 | 13.58 | 32.40 | 4.56 | 2.91 | 10.98 | 21.60 | 32.16 | 7.51 | 17.78 | 3.45 | 2.73 | 13.30 | 229.09 |

| July 2008 | 74.64 | 14.10 | 28.89 | 6.42 | 3.75 | 11.46 | 29.25 | 38.04 | 7.47 | 17.78 | 3.51 | 3.15 | 13.67 | 252.13 |

| January 2009 | 80.28 | 14.10 | 18.81 | 6.00 | 3.18 | 11.52 | 23.94 | 37.74 | 7.78 | 17.70 | 3.81 | 2.50 | 14.17 | 241.53 |

| July 2009 | 74.82 | 19.28 | 13.14 | 5.79 | 2.90 | 12.84 | 21.78 | 36.06 | 6.35 | 14.78 | 4.35 | 2.34 | 12.74 | 227.17 |

| January 2010 | 75.60 | 15.30 | 10.58 | 6.06 | 2.61 | 14.88 | 20.61 | 36.60 | 6.33 | 15.37 | 5.88 | 2.38 | 12.81 | 225.02 |

| July 2010 | 78.84 | 16.50 | 18.76 | 6.15 | 2.64 | 14.82 | 21.06 | 37.86 | 6.11 | 16.20 | 5.46 | 2.20 | 12.77 | 239.38 |

| January 2011 | 98.10 | 16.80 | 13.72 | 5.97 | 3.18 | 10.74 | 24.66 | 40.62 | 6.62 | 17.78 | 6.99 | 2.72 | 13.34 | 261.25 |

| July 2011 | 92.40 | 18.15 | 15.39 | 5.28 | 3.18 | 11.82 | 29.70 | 41.10 | 6.98 | 17.10 | 6.30 | 2.74 | 13.24 | 263.38 |

| January 2012 | 102.60 | 18.30 | 19.62 | 5.76 | 3.15 | 11.34 | 30.87 | 43.08 | 8.02 | 18.90 | 6.87 | 2.78 | 14.25 | 285.54 |

| July 2012 | 95.16 | 18.60 | 24.75 | 6.12 | 3.04 | 12.54 | 42.48 | 44.10 | 8.12 | 20.48 | 6.51 | 3.23 | 14.25 | 299.39 |

Notes: Prices are in nominal values, and refer to quantities stipulated in Executive Order (Decreto Lei) no. 399/1938.

Source: Prepared from data from DIEESE (2012a).

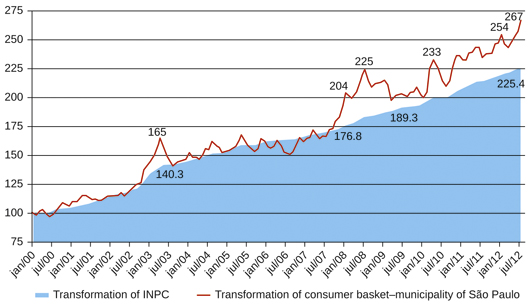

Figure 1 shows the increase in prices of items in the consumer basket as compared to the National Consumer Price Index (INPC). Till 2007, the two indicators registered a slight increase (in spite of a peak for the consumer basket in the middle of 2003). Till 2008, there were even periods in which the evolution of the cost of the consumer basket was below the INPC. However, from 2008 onwards, there was a clear separation of the two indicators, with the price increase of items in the consumer basket being above that of the general price index. There was a fall in prices thereafter upto August 2010, after which prices began to climb again and diverge from the general price index.

This situation continued upto 2012. The cost of the consumer basket in the middle of 2012 exhibited a growth of 167 per cent in relation to January 2000, while the INPC grew around 125 per cent in the same period.

Figure 1 Evolution of the prices of items in the consumer basket for the city of São Paulo, shown with the National Consumer Price Index (INPC) (January 2000=100)

Notes: The nominal value of the consumer basket and its products calculated by the DIEESE for the city of Sao Paulo, and the transformation of the INPC calculated by the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE). Values use January 2000 as base (Jan. 2000=100).

Source: Prepared through the use of data calculated by the DIEESE and the IBGE.

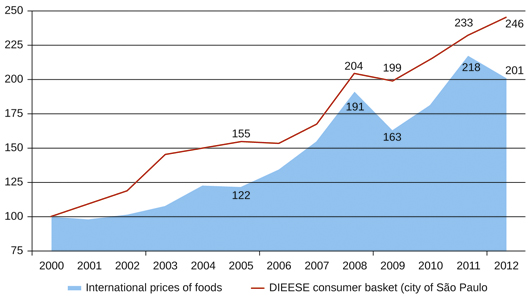

Figure 2 shows the evolution of prices of the consumer basket compared to the evolution of international prices of foods. It can be observed that the price changes of items of the consumer basket followed variations in international prices, with peaks in the years 2008 and 2011. In spite of the slight fall in 2009 and 2012 (only in the international indicator), it appears that there was a trend toward higher levels of prices, both domestically and internationally.

Figure 2 Evolution of the mean annual price of the consumer basket for the city of São Paulo, shown with international prices of food commodities (January 2000=100)

Notes: The consumer basket index corresponds to the annual mean of the nominal value calculated monthly by the DIEESE for the city of Sao Paolo. The international prices correspond to the Commodity Food Price Index, which includes price indices of cereals, vegetable oils, meat, shellfish, sugar, bananas, and oranges, calculated by the International Monetary Fund (World Economic Outlook Database, April 2012). Both indices are presented using January 2000 as base (Jan. 2000=100).

Source: Prepared using data provided by the DIEESE and the International Monetary Fund (IMF).

It is noteworthy that the increase in prices of the consumer basket was, in general, even greater than the increase in the international prices of foods. In addition, considering the two periods of price fall, in 2009, the costs of the consumer basket fell much less than the international prices of foods. From 2011 onwards, after a fall in the value of the basket, domestic prices continued to rise.

Bolsa Família and the Food Crisis

The Bolsa Família Programme (Decree no 5.209 of September 17, 2004) provides benefits to households classified as being in extreme poverty and poverty. The level of benefits depends on the composition of the family (such as the presence and number of pregnant women, children between the age of zero and 12, and adolescents). The levels of poverty and extreme poverty are established on the basis of the per capita income level of the family, as stated in the Decree that regulates the programme.15

The relevant per capita income intervals are shown in Table 3. Since the creation of the programme, those in extreme poverty have been guaranteed a minimum benefit, which rises by variable amounts depending on the presence of expectant mothers, nursing women, children up to the age of 12, adolescents up to the age of 15, and sixteen– or seventeen–year–old adolescents. Families in poverty have a right only to the variable benefits (and not to a minimum benefit).

Table 3 Per capita income intervals for households classified as being in poverty and extreme poverty under Bolsa Família in R$

| Period | Households in extreme poverty | Households in poverty |

| September 2004 | up to R$50 | R$50–100 |

| April 2006 | up to R$60 | R$60–120 |

| April 2009 | up to R$69 | R$69–137 |

| June 2009 | up to R$70 | R$70–140 |

Source: Based on Decree no. 5.209/2004 and its amendments.

Table 4 shows the minimum and maximum values of the programme benefits for families classified as being in poverty and in extreme poverty.

Table 4 Monthly benefits paid through the Bolsa Família Program, by classification and year in R$

| Period | Households in extreme poverty | Households in poverty | ||

| Minimum value | Maximum value | Minimum value | Maximum value | |

| September 2004 | 50 | 95 | 0 | 45 |

| July 2007 | 58 | 112 | 0 | 54 |

| June 2008 | 62 | 122 | 0 | 60 |

| July 2009 | 68 | 200 | 0 | 132 |

| June 2011 | 70 | 306 | 0 | 236 |

Notes: The maximum values assume the presence of three (five, from June 2011) pregnant women (since July 2007) or lactating mothers (since July 2007) or children between zero and 12 or adolescents up to 15 years; after July 2009, the family should also have two teenagers (aged 16 to 17) enrolled in schools.

Source: Based on Decree no. 5.209/2004 and its amendments.

To simulate the potential impact of the Bolsa Família Programme on access to food by families in poverty and extreme poverty, the standard family unit is assumed to have two adults and two children, and is assigned two quotas of the variable benefit of the programme.

Table 5 Simulated values of monthly Bolsa Família benefits for a standard family unit, different years in R$

| Period | Households in extreme poverty | Households in poverty |

| September 2004 | 80 | 30 |

| July 2007 | 94 | 36 |

| June 2008 | 102 | 40 |

| July 2009 | 112 | 44 |

| June 2011 | 134 | 64 |

Notes: The standard family unit comprises two adults and two children.

Source: Prepared by the authors.

Table 5 shows that, in September 2004, according to regulations of the programme at that time, the standard family would receive two variable quotas each of R$15, amounting to a total benefit of R$30. A family in a situation of extreme poverty would receive, in addition to these two quotas, the basic value of the benefit, which at that time was R$50 (or a total of $80).

Table 6 shows the simulated values of programme benefits payable to a standard family from January 2000 till the regulation by Decree no. 5.209 of September 17, 2004.

Table 6 Simulated values of monthly benefits of the income transfer programme for a standard family unit, at constant prices in R$

| Period | Households in extreme poverty | Households in poverty |

| January 2000 | 52.74 | 19.78 |

| July 2000 | 53.75 | 20.16 |

| January 2001 | 55.61 | 20.85 |

| July 2001 | 57.92 | 21.72 |

| January 2002 | 61.04 | 22.89 |

| July 2002 | 63.18 | 23.69 |

| January 2003 | 71.01 | 26.63 |

| July 2003 | 74.76 | 28.03 |

| January 2004 | 77.12 | 28.92 |

| July 2004 | 79.47 | 29.80 |

Notes: 1. The standard family unit comprises two adults and two children.

2. The values of the September 2004 benefits (R$80.00 and R$30.00)

to a standard eligible family were deflated by the INPC index (09/2004=100).

All prices are deflated to September 2004 levels using the INPC index.

Source: Prepared by the authors.

Table 7 shows the purchasing power of individuals with respect to the consumer basket, with and without Bolsa Família transfers. The standard per capita income cut-offs are used to identify those in poverty and extreme poverty. For those eligible to receive Bolsa Família benefits, the benefits for a standard family of four are added; the total is then divided by four to get the per capita contribution of Bolsa Família.

Table 7 Purchasing power of individuals in poverty and extreme poverty, with and without income transfers from the Bolsa Família Programme in R$ and per cent

| Period | Households in extreme poverty | Households in poverty | ||||||

| Without Bolsa Família | With Bolsa Família | Without Bolsa Família | With Bolsa Família | |||||

| Income (R$) | Share of basket that can be purchased with (2) (%) | Benefit amount (R$) | Share of basket that can be purchased with (2)+(4) (%) | Income (R$) | Share of basket that can be purchased with (6) (%) | Benefit amount (R$) | Share of basket that can be purchased with (6)+(8) (%) | |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

| January 2000 | 32.96 | 29 | 52.74 | 41 | 65.92 | 59 | 19.78 | 63 |

| July 2000 | 33.59 | 30 | 53.75 | 42 | 67.19 | 60 | 20.16 | 65 |

| December 2000 | 34.49 | 29 | 55.18 | 40 | 68.98 | 58 | 20.69 | 62 |

| July 2001 | 36.20 | 29 | 57.92 | 40 | 72.40 | 58 | 21.72 | 62 |

| January 2002 | 38.15 | 30 | 61.04 | 41 | 76.30 | 59 | 22.89 | 63 |

| July 2002 | 39.49 | 29 | 63.18 | 41 | 78.97 | 59 | 23.69 | 63 |

| January 2003 | 44.38 | 27 | 71.01 | 38 | 88.76 | 55 | 26.63 | 59 |

| July 2003 | 46.72 | 29 | 74.76 | 40 | 93.44 | 58 | 22.03 | 62 |

| January 2004 | 48.20 | 28 | 77.12 | 39 | 96.41 | 56 | 22.92 | 61 |

| July 2004 | 49.67 | 29 | 79.47 | 40 | 99.33 | 57 | 29.80 | 61 |

| January 2005 | 50.00 | 29 | 80.00 | 40 | 100.00 | 58 | 30.00 | 62 |

| July 2005 | 50.00 | 28 | 80.00 | 39 | 100.00 | 56 | 30.00 | 60 |

| January 2006 | 50.00 | 28 | 80.00 | 39 | 100.00 | 56 | 30.00 | 61 |

| July 2006 | 60.00 | 35 | 80.00 | 47 | 120.00 | 70 | 30.00 | 75 |

| January 2007 | 60.00 | 32 | 80.00 | 43 | 120.00 | 65 | 30.00 | 69 |

| July 2007 | 60.00 | 32 | 94.00 | 45 | 120.00 | 64 | 36.00 | 69 |

| January 2008 | 60.00 | 26 | 94.00 | 36 | 120.00 | 52 | 36.00 | 56 |

| July 2008 | 60.00 | 24 | 102.00 | 34 | 120.00 | 48 | 40.00 | 52 |

| January 2009 | 60.00 | 25 | 102.00 | 35 | 120.00 | 50 | 40.00 | 54 |

| July 2009 | 70.00 | 31 | 112.00 | 43 | 140.00 | 62 | 44.00 | 66 |

| January 2010 | 70.00 | 31 | 112.00 | 44 | 140.00 | 62 | 44.00 | 67 |

| July 2010 | 70.00 | 29 | 112.00 | 41 | 140.00 | 58 | 44.00 | 63 |

| January 2011 | 70.00 | 27 | 112.00 | 38 | 140.00 | 54 | 44.00 | 58 |

| July 2011 | 70.00 | 27 | 134.00 | 39 | 140.00 | 53 | 64.00 | 59 |

| January 2012 | 70.00 | 25 | 134.00 | 36 | 140.00 | 49 | 64.00 | 55 |

| July 2012 | 70.00 | 23 | 134.00 | 35 | 140.00 | 47 | 64.00 | 52 |

Notes: 1.

All simulated values are deflated to September 2004

levels using the INPC index (the official inflation index).

2. To calculate the value of benefits, a standard family of four

with two adults and two children and which met the eligibility criteria of the

programme was considered.

3. The value of the consumer basket calculated by the DIEESE (2012a)

for the city of São Paulo was used.

4. Per capita incomes correspond to cut-offs used to characterise families as being in poverty and extreme poverty.

5. In cases where the families received the Bolsa Família benefits,

the per capita value of the benefit was added (for a standard family).

Source: Prepared by the authors.

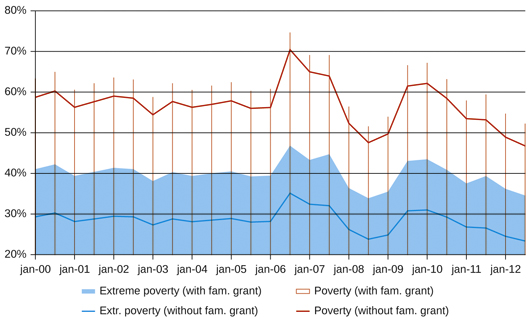

The most significant finding of this analysis is that neither people classified to be in extreme poverty nor those classified to be in poverty were capable of purchasing the consumer food basket, even with benefits from the Bolsa Famìlia. Over the years, the purchasing power ranged from 23 per cent to 35 per cent of the consumer basket for individuals in extreme poverty and from 47 per cent to 70 per cent for those in poverty. As noted earlier, the consumer basket refers to a “Minimum Essential Allowance” sufficient for feeding an adult person. These estimates show that even if one spent the entire available budget only on foods in the consumer basket, it would not be possible for all individuals to have economic access to all the essential commodities.

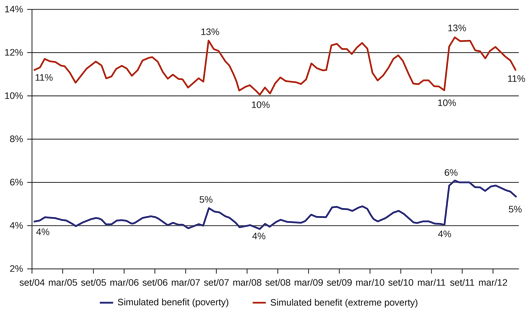

The following figure shows that if we add the values of the simulated benefits received under Bolsa Família to the per capita income, the ability to purchase the consumer basket expands, at most, to 47 per cent (extreme poverty) and 75 per cent (poverty).

Figure 3 Ability to purchase the consumer basket by individuals in a situation of poverty and extreme poverty including simulated benefits of the Bolsa Família Program, São Paulo

Notes: 1. The values of the income ranges and the benefits for the period

prior to the Family Grant Programme were obtained through deflation of the

value of September 2004 using the INPC.

2. For calculation of the value of the benefit, a family with four

people, that is, two adults and two children that fit within the eligibility

criteria of the programme, was considered.

3. The value of the consumer basket calculated by the DIEESE (2012a)

for the city of Sao Paulo was considered.

4. To calculate purchasing power, the per capita incomes at the cut-offs

for characterisation of the situations of poverty and extreme poverty were

taken into account. In situations of receiving the Family Grant, the per capita

value of the benefit was added (considering a standard family of four people).

Source: Prepared by the authors.

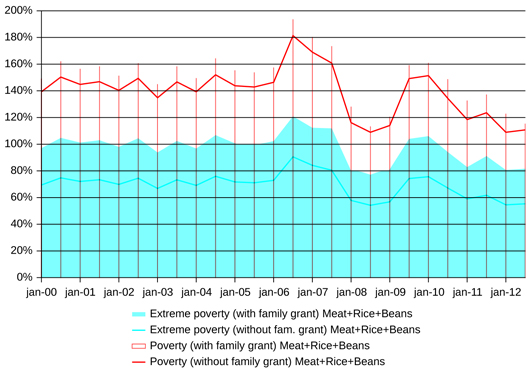

Figure 4 and Table 8 show data on the purchasing power of individuals for three products: rice, beans, and meat. These are the typical food items consumed by most Brazilians, and represent, according to the POF data examined in this study, the major components of food expenses of families living in poverty and extreme poverty.

Figure 4 Ability to purchase three food items (meat, rice, and beans) by individuals in a situation of poverty and extreme poverty including simulated benefits of the Bolsa Família Programme, São Paulo

Notes: See Table 8.

Source: Prepared by the authors.

Figure 4 shows that individuals in extreme poverty would not be capable of acquiring even these three items of food. Even if the simulated value of the Bolsa Família benefits were added, a person in extreme poverty would lack the required purchasing power. Of course, consumption only of these three foods would not ensure the daily quantity of micronutrients necessary for bodily maintenance (especially vitamins and minerals) (News.Med.Br 2007).

Table 8 Ability of individuals to buy requirements of meat, rice, and beans in situations of poverty and extreme poverty, with and without Bolsa Família transfers in R$ and per cent

| Period | Individual in extreme poverty | Individual in poverty | ||||||

| Without Bolsa Família | With Bolsa Família | Without Bolsa Família | With Bolsa Família | |||||

| Cut-off income (R$) | Requirement of Meat+Rice+Beans that can be purchased with (2) (%) | Simulated benefit (R$) | Requirement of Meat+Rice+Beans that can be purchased with (2)+(4) (%) | Cut-off income (R$) | Requirement of Meat+Rice+Beans that can be purchased with (6) (%) | Simulated benefit (R$) | Requirement of Meat+Rice+Beans that can be purchased with (6)+(8) (%) | |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

| January 2000 | 32.96 | 70 | 52.74 | 98 | 65.92 | 140 | 19.78 | 150 |

| January 2005 | 50.00 | 72 | 50.00 | 101 | 100.00 | 144 | 30.00 | 155 |

| July 2012 | 70.00 | 56 | 134.00 | 82 | 140.00 | 111 | 64.00 | 124 |

Notes: 1. The values of the income intervals and the benefits for the

period prior to the Bolsa Família Programme were obtained through deflation

with of the value of INPC for September 2004.

2. For calculation of the value of the benefit, a family with four

people (i.e., two adults and two children, that fit the eligibility criteria of

the program) was considered.

3. The values and quantities of the foods “meat,” “rice,” and

“beans” in the form calculated by the DIEESE (2012a) for the consumer basket in

reference to the city of São Paulo were used.

4. Per capita incomes correspond to cut-offs used to characterise families as being in poverty and extreme poverty. In cases where the family received Bolsa Família benefits, the per capita value of the benefit for a standard family was added.

Source: Prepared by the authors.

Even after the recent period of expansion of the value of the benefit of the Programme, incomes in July 2012, for example, for an individual in extreme poverty, would only be adequate to purchase 82 per cent of the requirement of meat, rice, and beans (Table 8).

The data in Figures 3 and 4 show that individuals in extreme poverty and individuals in poverty experienced a sharp fall in purchasing power in the period 2008–10 — a period characterised in this paper as one of global food crisis — and that this capacity remained at relatively lower levels after 2010 as compared to previous years.

Figures 5 and 6 attempt to assess the contribution of the Bolsa Família Programme to individuals in situations of poverty and extreme poverty, in terms of their ability to maintain their purchasing power. Figure 5 shows a reduction in the ability to purchase the consumer basket in 2008 when compared to the period immediately prior to the crisis, but the transfer of income through Bolsa Família allowed individuals to maintain approximately the same purchasing power as before, especially for those living in poverty (but not for those in extreme poverty).

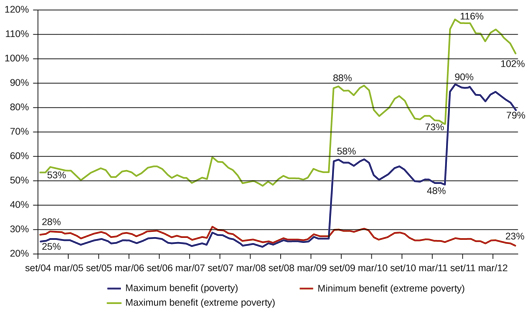

Figure 5 Ability to purchase the consumer basket from benefits of the Bolsa Família Programme (simulated per capita benefit)

Notes: For calculation of the value of the benefit, a standard family of four (i.e., two adults and two children, that fit the eligibility criteria of the Programme) was considered. The benefit value was then divided among the four people to obtain benefit per capita. The value of the consumer basket calculated by the DIEESE for the city of Sao Paulo was used.

Source: Prepared by the authors.

In 2011, with another rise in the prices of the consumer basket, the increase in the benefits of the Bolsa Família Programme permitted an expansion in food purchasing power, from 10 per cent to 13 per cent for individuals in extreme poverty and from 4 per cent to 6 per cent for those in poverty. Nevertheless, it is necessary to look at the manner in which the increase in benefits occurred.

The increases in the maximum value of the Bolsa Família benefits (Figure 6) in 2009 and 2011 are fundamentally due to the expansion of the variable benefits component, which depends on the composition of the family group. In 2009, benefits were created for adolescents (aged 16 and 17), with the possibility of up to two additional quotas; in 2011, the number of variable quotas of the benefit was expanded from five to seven.

Figure 6 provides an indication of the distortions in purchasing power created by the Programme. To be able to obtain the maximum benefit, which was sufficient to buy a consumer basket in March 2012, a family in extreme poverty would have required a member profile that permitted it to be eligible for all the variable quotas and benefits distributed by the Bolsa Família. On the other hand, the minimum benefit, corresponding to 28 per cent of the consumer basket when the Programme was created, is currently capable of buying only 23 per cent of the consumer basket. To put it differently, our simulations show that the degree of purchasing power was linked to family composition, and for households that did not have the desired profile, the purchasing power of the minimum benefit fell.

Figure 6 Ability to purchase the consumer basket from the benefits of the Bolsa Família Programme (maximum and minimum benefits) for families in poverty and extreme poverty

Notes: The basic benefit is for families in extreme poverty. The variable benefits considered were those that depend on the presence in the family of up to five expectant mothers, nursing mothers, children upto 12 years old or adolescents upto 15 years old, and of two adolescents of 16 or 17 years old. The value of the consumer basket calculated by the DIEESE for the city of Sao Paulo was used.

Source: Prepared by the authors.

Thus, even with the increases in the benefits paid by the Programme, the purchasing power provided was not able to expand correspondingly. We observed a sharp decline in the purchasing power of basic food for families whose profile allowed access only to the minimum benefit. Such a situation is likely to worsen in a period of structural inflation with respect to food items.

Conclusion

Economic access to food depends on both income and food prices. While food security has improved in Brazil in recent years, a considerable section of the population is still living in vulnerable conditions. The lower the income of individuals, the more critical their situation in terms of access to a minimum food basket.

The data presented in this paper suggest that while the programmes of the Lula government represented significant political action towards combating hunger, the policies were insufficient to solve the problem of food deprivation. Our estimates showed that even if all poor and extremely poor families received the simulated benefits of the Bolsa Família Programme, this would still not ensure access to the minimum food basket. In other words, such families and individuals would not be defined as food secure. Access to food is likely to be critical in a period of higher prices of foods such as observed globally in recent years.

In spite of the prominence of the Bolsa Família Programme, an initiative now strongly recommended by multilateral organisations like the FAO, the World Bank, and the IMF as potentially easing the impact of food inflation, the evidence from this paper is that hunger is a universal social problem within the system of capitalism, with a much greater incidence in underdeveloped and dependent countries. Specific policies such as the Bolsa Família are structurally incapable of ensuring adequate food security, as they do not address the sources of structural inflation emerging from capitalist development in countries at the periphery.

Furthermore, programmes like Bolsa Família are government-led programmes, and their continuity depends on political decisions as well as the economic conditions of each country. In Brazil, the current government in 2001 introduced “Brazil without Misery,” a new plan to combat poverty, This plan was implemented in 2012, combined with “Brazil Caring,” another programme for income supplementation. These initiatives suggest that the present government recognised the insufficiency of the actions taken by the Lula governments. These policies are income transfers, which, as shown in this study, cannot ensure adequate access to foods in the context of a global food crisis.

Acknowledgements: An earlier version of the paper was presented at the Tenth Anniversary Conference of the Foundation for Agrarian Studies, Kochi, January 9-12, 2014. We are grateful to two referees of this journal for their detailed comments and editorial advice.

Appendix

A1. The Bolsa Família Program

The Bolsa Família Programme promotes food and nutritional safety and contributes towards achieving citizenship for sectors of the population most vulnerable to hunger. The Bolsa Família is a conditional cash transfer programme with conditionalities, which serves poor families (monthly income per person between R$77.01 and R$154) and extremely poor (monthly income per person upto R$77). It has several types of benefits.

These benefits are based on family profiles. The criteria are: monthly income per person, the number of members, the total number of children and adolescents up to the age of 17 years, and the presence of pregnant women. There is currently a basic benefit of R$77 granted only to extremely poor families (defined as households where the monthly income per person is under $77). To this can be added several variable benefits: 1) R$35 is granted to families with children or adolescents between the ages of 0–15 years; 2) R$35 is granted to families with pregnant women; and 3) R$35 is granted to families with children aged between 0 and 6 months (Mourão and Jesus 2011, p. 44).16

The programme has three main components: income transfers, conditionalities or eligibility conditions, and supplementary programmes. The management of Bolsa Família is decentralised and shared between the Union, States, and Municipalities. These three federal entities work together to implement and monitor the programme. The list of beneficiaries is public and can be accessed by any citizen (MDS 2011). The conditions that make families eligible to the right to receive the Bolsa Família financial benefits are: (a) monitoring of the vaccination cards and the growth and development of children under seven; (b) attendance of women in the age group 14–44 years at medical check-ups and, if pregnant or breastfeeding, at prenatal sessions, and health check-ups for mother and baby; (c) all children and teenagers between 6 and 15 years old must be registered with a school and attend a minimum of 85 per cent of classes in the scheduled time-table per month; (d) students between 16 and 17 years old must have a minimum attendance of 75 per cent; (e) children and teenagers upto 15 years old at risk of child labour or those rescued by the Child Labour Eradication Programme must participate in the Cohabitation and Strengthening of Bonds Services and attend a minimum of 85 per cent of scheduled classes per month.

The eligibility criteria for participating in the Bolsa Família programme are based on per capita family income. Bolsa Família selects families based on information provided by municipalities to the Single Social Programme Register (MDS 2011). Registered people are selected by means of an automated process, and registration does not imply the immediate entry of families into the programme (Mourão and Jesus 2011).

A2. Technical Note on the Brazilian Survey of Family Budgets

The most recent Household Budget Survey (POF) was conducted in Brazil in the year 2007–8; the survey immediately preceding it was undertaken in 2002–3. The sample design of the last two POFs (budget surveys) was structured in such a way that results could be published at the following levels: Brazil, major regions (North, Northeast, Southeast, South, and Centre–West), and by urban and rural areas. At the Federation level, results are reported for all regions and for urban regions. In nine metropolitan areas and for the capital of the Federative Units, results correspond to urban areas.

The POF data are collected over a period of 12 months, and the reference period is up to 12 months. Therefore, the data span a total period of 24 months. During this 24-month period, absolute and relative price changes occur, thus creating a need for the amounts collected in the survey to be valued at a suitable price. The individual food intake data is collected for persons aged 10 years or above, for two non-consecutive days in a subsample of households, providing an evaluation of the nutritional status of the population. The date fixed for the compilation, analysis and presentation of results of POF 2008–9 was January 15, 2009.

POF 2008–9 adopted a two-stage cluster sampling method with geographical and statistical stratifications of primary sampling units that corresponded to census sectors on the geographical basis of the 2000 Population Census. A sub-sample of sectors for the 2008–9 POF was selected by simple random sampling in each stratum. In the plan adopted, the secondary sampling units were the permanent households, which were selected by simple random sampling without replacement within each of the selected sectors. The sectors were distributed over the four quarters of the survey, ensuring that, in every quarter, the geographic and socio-economic data were represented by the selected households.

The effective sample size was 4696 census sectors, corresponding to an expected number of 59,548 households. More detailed information on the methodology of POF can be obtained from IBGE (2011).

A3. Legislation

In Brazil, unfortunately, the government does not have objective, scientific criteria for its definitions of the poverty and extreme poverty lines. There are academic studies that determine more consistent values, but these are not followed by the authorities and government policies. Definitions of poverty and extreme poverty were based on legal decrees and changed over the years as noted below.

Extreme poverty:

- Decree no 5.209 of September 17, 2004 — per capita monthly family income of up to R$50.00

- Decree no. 5.749 of April 11, 2006 — per capita monthly family income of up to R$60.00

- Decree no. 6.824 of April 16, 2009 — per capita monthly family income of up to R$69.00

- Decree no. 6.917 of July 30, 2009 — per capita monthly family income of up to R$70.00

Poverty:

- Decree no. 5.209 of September 17, 2004 — per capita monthly family income up to R$100.00

- Decree no. 5.749 of April 11, 2006 — per capita monthly family income up to R$120.00

- Decree no. 6.824 of April 16, 2009 — per capita monthly family income up to R$137.00

- Decree no. 6.917 of July 30, 2009 — per capita monthly family income up to R$140.00

The eligibility criteria and benefits of the Bolsa Família programme underwent the following changes:

- Decree no 5.209 of September 17, 2004 — for families in extreme poverty, the basic benefit was set at the value of R$50.00; for them and for families in poverty, a variable benefit of R$15.00 per child up to 15 years of age was created, with a maximum limit of R$45.00.

- Decree no. 6.157 of July 16, 2007 — changed the basic benefit to R$58.00 and the variable benefit to R$18.00, up to the limit of R$54.00. This is now directed to family units that include expecting mothers, nursing women, children between 0–12 years of age, or adolescents up to fifteen years old.

- Decree no. 6.491 of June 26, 2008 — the values of the basic benefit were changed to R$62.00, and the values of the variable benefit to R$20.00, up to a limit of R$60.00.

- Decree no. 6.917 of July 30, 2009 — the values of the basic benefit were changed to R$68.00, of the variable benefit to R$22.00, up to a limit of R$66.00, and the benefit for the adolescent at the value of R$33.00 up to a limit of R$66.00.

- Decree no. 7.447 of March 1, 2011 and Decree no. 7.494 of June 2, 2011 — the values of the basic benefit were changed to R$70.00, of the variable benefit to R$32.00, up to a limit of R$160.00, and of the benefit for the adolescent to R$38.00 up to a limit of R$76.00.

Notes

1 Individuals with an average consumption of less than 1900 calories are defined as undernourished. The average consumption among undernourished persons was 1650 calories.

3 The Zero Hunger Programme has come to attract ever-greater international recognition. In 2011, the Brazilian José Graziano da Silva, the former minister driving the programme and the then President of the regional headquarters of the FAO in Latin America and the Caribbean, where he had served since 2006, came to hold the post of Director General of the FAO. Also in this year, Brazil received two international distinctions for efforts in combating hunger: the non-governmental organisation ActionAid identified Brazil as the country most prepared for combating hunger from a list of 28 less-developed countries, and the World Food Prize award was given to former President Lula for his efforts to end hunger (Stangler 2011).

5 Inflation is an important issue considering the levels observed in the 1980s, before the Real Plan. Then, the real purchasing power of the poor was much more affected than that of other social groups because they did not have access to protective mechanisms such as financial instruments. There are studies showing the positive effect of stabilisation on equality, although it is a one-time effect. See Cardoso (1992) and Cardoso et al. (1995).

6 The basic consumer basket, is defined as a group of the most commonly bought food and household items. Currently, the minimum salary allows the purchase of 2.24 consumer baskets, the highest registered since 1979 (DIEESE 2012).

7 The index number covering all of 2007 (not taking account of food products) was 35 per cent less than the index number including food products.

8 The choice of the consumer basket has two reasons. The first is the impossibility of setting up a specific consumer basket based on expenses identified by the Family Budget Survey (POF). The second is that the items that form this consumer basket are among the main expenses of families, especially those with lower incomes.

10 PRODEA (Portuguese: “Programa de Distribuição Emergencial de Alimentos”; English: “Emergency Food Distribution Programme”) was a programme created in 1994 under the Fernando Henrique Cardoso government, and thus was an antecedent to the Bolsa Família Programme.

11 For examples of the international debate, see FAO (2006, 2009), Rosegrant and Cline (2003), and Mittal (2009).

12 POF 3 (“Sheet of Collective Acquisition”) is a questionnaire that includes information on monetary and non-monetary acquisition of foods, drinks, personal care products and cleaning products, fuels for domestic use, and other products that tend to be purchased frequently and, in general, serve all dwellers. The POF 4 questionnaire (“Questionnaire of Individual Acquisition”) collects data on the type of acquisition of products and respective monetary and non-monetary expenses on products and the monetary expenses made on services and characterises the data by individual use or purpose, such as communications, transport, education, eating out, tobacco products, games and betting, recreational activities, use and purchase of cell phones, pharmaceutical products and health services, perfumery articles and skin and hair products, hairstyling services and others, stationery and reading items and subscriptions to periodicals, clothing and shoes, fabrics and bathing wear, travel, vehicle purchase and maintenance. The survey also investigated individual expenditure on banking and professional services, ceremonies and parties, jewellery, expenses on other properties, labour contributions and pensions. In the questionnaire of individual expenses, just as in the collective expense questionnaire and record, information was gathered regarding establishments in which products and services were acquired and the manner of obtaining the acquisition made, by units of consumption.

13 São Paulo is one of the 27 Brazilian federative units and is the most populous of them. We selected this unit arbitrarily, only to be able to conduct the analysis at a sub-national level.

14 Observing the database at the lowest level of aggregation made available, the item “Other foods” refers, in fact, to nine sets of foods: Easter Basket, Christmas Basket, Breakfast Basket, Consumer Basket, Open-Air Market, Fruit and Vegetable, Shop and Aggregate, and two others defined only in Portuguese. These are Feirinha and Sacola COBAL (COBAL is the Portuguese abbreviation for the Brazilian Enterprise for Food, a state company that is responsible for food distribution).

16 Values based on April 2011 figures. See http://www.mds.gov.br/bolsafamilia/noticias, viewed on August 25, 2011.

References

| Alves, Maria Magdalena (2011). “Fome, Não dá pra Esquecer (Hungry, You Cannot Forget),” Webartigos, available at http://www.webartigos.com/articles/56300/1/FOME-NAO-DA-PRA-ESQUECER/pagina1.html, viewed on April 7, 2015. | |

| Belik, Walter (2003), Segurança Alimentar: a Contribuiçäo das Universidades (Food Security: The Contribution of Universities), Instituto Ethos, Curitiba. | |

| Campello, Tereza, and Neri, Marcelo (2013), Programa Bolsa Família : Uma Década de Inclusão e Cidadania (Bolsa Família Program: a Decade of Inclusion and Citizenship), Instituto de Pesquisa Econômica Aplicada (Applied Economic Research Institute) (IPEA), Brazil. | |

| Cardoso, Eliana (1992), “Inflation and Poverty,” Working Paper, no.406, National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge, available at http://www.nber.org/papers/w4006.pdf, viewed on April 7, 2015. | |

| Cardoso, Eliania, Paes de Barros, Ricardo, and Urani, Andre (1995), “Inflation and Unemployment as Determinants of Inequality in Brazil: The 1980s,” in Dornbusch, Rudiger and Edwards, Sebastian (eds.) (1985), Reform, Recovery, and Growth: Latin America and the Middle East, available at http://www.nber.org/chapters/c7655.pdf, viewed on April 7, 2015. | |

| Couto, Ebenézer Pereira (2010), “Economia Política dos Preços de Alimentos, Instabilidade Econômica e Regulação no Capitalismo Contemporâneo (The Political Economy of Food Prices, Economic Instability and Regulation in Contemporary Capitalism),” in Almeida Filho, Niemeyer, and Ramos, Pedro (eds.) (2010), Segurança Alimentar: Produção Agrícola e Desenvolvimento Territorial (Food Security: Agricultural Production and Territorial Development), Editora Alínea, Campinas, pp. 279–304. | |

| Departamento Intersindical de Estatística e Estudos Socioeconômicos (Inter-Trade Union Department of Statistics and Socio-Economic Studies) (DIEESE) (1993), “Cesta Básica Nacional: Metodologia (National Basic Food Basket: Methodology),” available at https://www.dieese.org.br/metodologia/metodologiaCestaBasica.pdf, viewed on April 7, 2015. | |

| DIEESE (2012), “Nota Tecnica: Política de Valorização do Salário Mínimo: Considerações Sobre o Valor a Vigorar a Partir de 1º de Janeiro de 2012 (Technical Note: Minimum Wage Enhancement Policy: Considerations on the Value Effective as of January 1, 2012),” no. 106, Dec 2011, revised Jan 2012, available at http://www.dieese.org.br/notatecnica/notatec106PoliticaSalarioMinimo.pdf, viewed on April 7, 2015. | |

| Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) (2006), “Policy Brief: Food Security,” no. 2, Jun, available at ftp://ftp.fao.org/es/esa/policybriefs/pb_02.pdf, viewed on April 7, 2015. | |

| FAO (2009), “Declaration of the World Summit on Food Security,” available at http://www.fao.org/fileadmin/templates/wsfs/Summit/Docs/Final_Declaration/WSFS09_Declaration.pdf, viewed on April 7, 2015. | |

| FAO (2011), “Global Statistics Service — Food Security

Indicators: Brazil,” available at http://www.fao.org/fileadmin/templates/ess/documents/food_security_statistics/ monitoring_progress_by_country_2003-2005/Brazil_e.pdf, viewed on April 7, 2015. | |

| FAO (2011a), The State of Food Insecurity in the World: How does International Price Volatility Affect Domestic Economies and Food Security?, FAO, Rome, available at http://www.fao.org/docrep/014/i2330e/i2330e.pdf, viewed on April 7, 2015. | |

| FAO (2011b), The Millennium Development Goals Report: 2011, United Nations, New York, available at http://www.un.org/millenniumgoals/pdf/%282011_E%29%20MDG%20Report%202011_Book%20LR.pdf, viewed on April 7, 2015. | |

| FAO (2012), “The FAO Hunger Map 2014: Interactive Hunger Map,” available at http://www.fao.org/hunger/en/#jfmulticontent_c130584-2, viewed on April 7, 2015. | |

| FAO (2012a), “World Food Day, 16 October 2012,” available at http://www.fao.org/world-food-day/history/wfd2012/en/, viewed on April 7, 2015. | |

| Grosh, Margaret, del Ninno, Carlo, and Daniel Teslquc, Emil (2008), Guidance for Responses from the Human Development Sector to Rising Food and Fuel Prices, Washington, DC: World Bank, viewed on August 5, 2011. | |

| Hall, Anthony (2006), “From Fome Zero to Bolsa Família: Social Policies and Poverty Alleviation under Lula,” Journal of Latin American Studies, vol. 38, no. 4, pp. 689-709. | |

| Instituto Brasileiro de Geografica e Estatica (Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics) (IBGE) (2010a), “PNAD — Segurança Alimentar 2004–9: Insegurança Alimentar Diminui, mas Ainda Atinge 30.2 per cent dos Domicílios Brasileiros (National Household Survey — Food Security 2004–9: Food Insecurity Decreases, but Still Reaches 30.2 per cent of Brazilian Households),” Nov 26, available at http://www.ibge.gov.br/home/presidencia/noticias/noticia_impressao.php?id_noticia=1763, viewed on April 7, 2015. | |

| IBGE (2010b), “Pesquisa de Orçamentos Famíliares 2008–9 (Consumer Expenditure Survey 2008–9),” available at http://www.ibge.gov.br/home/estatistica/populacao/condicaodevida/pof/2008_2009/POFpublicacao.pdf, viewed on April 7, 2015. | |

| IBGE (2010c), “Pesquisa de Orçamentos Famíliares 2008–9: Microdados (Consumer Expenditure Survey 2008–9: Microdata),” available at http://www.ibge.gov.br/home/estatistica/populacao/condicaodevida/pof/2008_2009/microdados.shtm, viewed on April 7, 2015. | |

| IBGE (2010d), “Pesquisa Nacional por Amostra de Domicílios: Segurança Alimentar 2004–9 (National Survey of Households: Food Security 2004–9),” available at http://www.ibge.gov.br/home/estatistica/populacao/seguranca_alimentar_2004_2009/pnadalimentar.pdf, viewed on April 7, 2015. | |

| IBGE (2010e), “Pesquisa Nacional por Amostra de Domicílios: Síntese de Indicadores 2009 (National Survey of Households: Summary of Indicators 2009),” available at http://www.ibge.gov.br/home/estatistica/populacao/trabalhoerendimento/pnad2009/, viewed on April 7, 2015. | |

| IBGE (2011), “Pesquisa de Orçamento Famíliar 2008–9

(Family Budget Survey 2008–9) (POF): Análise do Consumo Alimentar Pessoal no

Brasil (Analysis of Individual Food Consumption in Brazil),” available at http://www.ibge.gov.br/home/estatistica/populacao/condicaodevida/pof/ 2008_2009_analise_consumo/pofanalise_2008_2009.pdf, viewed on April 7, 2015. | |

| Lavinas, Lena (1998), “Acessibilidade Alimentar e Estabilização Econômica no Brasil nos Anos 90 (Food accessibility and Economic Stabilization in Brazil in the ‘90s),” Discussion Text, no. 591, available at http://www.ipea.gov.br/pub/td/td0591.pdf, viewed on April 7, 2015. | |

| Ministerio do Desenvolvimento Social e Combate à Fome (Ministry of Social Development and Combating Hunger) (MDS) (2011), “Bolsa Família,” available at http://www.mds.gov.br/bolsafamilia, viewed on April 7, 2015. | |

| Mittal, Anuradha (2009), “The 2008 Food Price Crisis: Rethinking Food Security Policies,” G-24 Discussion Paper, no. 56, Jun, available at http://unctad.org/en/Docs/gdsmdpg2420093_en.pdf, viewed on April 7, 2015. | |

| Mourão, Luciana, and Jesus, Anderson Macedo de (2011), “Bolsa Família (Family Grant) Programme: An Analysis of Brazilian Income Transfer Programme,” Field Actions Science Reports, Special Issue 3: Brazil, available at http://factsreports.revues.org/1314, viewed on April 8, 2015. | |

| News.Med.Br (2007), “Prato dos Brasileiros: no Arroz

com Feijão e Carne Sobram Carboidratos, Proteínas e Gorduras, mas Faltam Vitaminas

e Minerais (The Brazilian Dish Rice with Beans and Meat Abounds in Carbohydrates,

Proteins and Fats, but Lacks Vitamins and Minerals),” available at http://www.news.med.br/p/saude/11862/prato-dos-brasileiros-no-arroz-com-feijao-e-carne-sobram- carboidratos-proteinas-e-gorduras-mas-faltam-vitaminas-e-minerais.htm, viewed on April 7, 2015. | |

| Ortega, Antônio César (2010), “Segurança Alimentar, Desenvolvimento e Enfoque Territorial Rural: Uma Proposta (Food Security, Rural Development, and Territorial Approach: A Proposal),” in Almeida Filho, Niemeyer, and Ramos, Pedro (eds.) (2010), Segurança Alimentar: Produção Agrícola e Desenvolvimento Territorial (Food Security: Agricultural Production and Territorial Development), Editora Alínea, Campinas, pp. 193–224. | |

| Rosegrant, M. W., and Cline, S. A. (2003), “Global Food Security: Challenges and Policies,” Science, vol. 302, no. 12, Dec, pp. 1917–9. | |

| Stangler, Jair (2011), “Brasil Sem Miséria: Passados

dez Anos, Fome Zero Quintuplica Investimento e Serve de Modelo Para Outros Países

(Brazil Without Poverty: After Ten Years, Zero Hunger Quintuples Investment and

Serves as a Model for Other Countries),” Estadao:

Radar Politico, Oct 16, available at http://politica.estadao.com.br/blogs/radar-politico/passados-dez-anos-fome- zero-quintuplica-investimento-e-serve-de-modelo-para-outros-paises/, viewed on April 7, 2015. | |

| Vivero, José Luis, and Almeida Filho, Niemeyer (2010), “A Consolidação do Combate à Fome e do Direito à Alimentação nas Agendas das Políticas da América Latina (The Consolidation of the Fight against Hunger and the Right to Food in the Policy Agenda in Latin America),” in Almeida Filho, Niemeyer, and Ramos, Pedro (eds.) (2010), Segurança Alimentar: Produção Agrícola e Desenvolvimento Territorial (Food Security: Agricultural Production and Territorial Development), Editora Alínea, Campinas, pp. 29–54. | |

| World Bank (2008), “Rising Food Prices: Policy Options and World Bank Response,” available at http://siteresources.worldbank.org/NEWS/Resources/risingfoodprices_backgroundnote_apr08.pdf, viewed on April 7, 2015. |

Decrees of the Government of Brazil

| Decreto Lei no. 399, de 30 de Abril de 1938 (Decree-Law no. 399 of April 30, 1938), available at http://www2.camara.gov.br/legin/fed/declei/1930-1939/decreto-lei-399-30-abril-1938-348733-publicacaooriginal-1-pe.html, viewed on April 7, 2015. | |

| Decreto no. 5.209, de 17 de Setembro de 2004 (Decree no. 5.209 of September 17, 2004), available at http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_ato2004-2006/2004/decreto/d5209.htm, viewed on April 7, 2015. | |

| Decreto no. 5.749, de 11 de Abril de 2006 (Decree no. 5.749 of April 11, 2006), available at http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_ato2004-2006/2006/Decreto/D5749.htm, viewed on April 7, 2015. | |

| Decreto no. 6.157, de 16 de Julho de 2007 (Decree no. 6.157 of July 16, 2007), available at http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_Ato2007-2010/2007/Decreto/D6157.htm, viewed on April 7, 2015. | |

| Decreto no. 6.491, de 26 de Junho de 2008 (Decree no. 6.491 of June 26, 2008), available at http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_Ato2007-2010/2008/Decreto/D6491.htm, viewed on April 7, 2015. | |

| Decreto no. 6.824, de 16 de Abril de 2009 (Decree no. 6.824 of April 16, 2009), available at http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_Ato2007-2010/2009/Decreto/D6824.htm, viewed on April 7, 2015. | |

| Decreto no. 6.917, de 30 de Junho de 2009 (Decree no. 6.917 of June 30, 2009), available at http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_Ato2007-2010/2009/Decreto/D6917.htm, viewed on April 7, 2015. | |

| Decreto no. 7.447, de 1 de Março de 2011 (Decree no. 7.447 of March 1, 2011), available at http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_Ato2011-2014/2011/Decreto/D7447.htm, viewed on April 7, 2015. | |

| Decreto no. 7.494, de 02 de Junho de 2011 (Decree no. 7.494 of June 2, 2011) available at http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_Ato2011-2014/2011/Decreto/D7494.htm#art1, viewed on April 7, 2015. | |

| Lei no. 10.836, de 9 de Janeiro de 2004 (Law no. 10.836 of January 9, 2004), available at http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_ato2004-2006/2004/lei/l10.836.htm, viewed on April 7, 2015. | |

| Lei no. 11.346, de 15 de Setembro de 2006 (Law no. 11.346 of September 15, 2006), available at http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_ato2004-2006/2006/lei/l11346.htm, viewed on April 7, 2015. | |

| Lei no. 8.742, de 7 de Dezembro de 1993 (Law no. 8.742 of December 7, 1993), available at http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/leis/l8742.htm, viewed on April 7, 2015. | |

| Medida Provisória no. 132, de 20 de Outubro de 2003 (Interim Measure no. 132 of October 20, 2003), available at http://www010.dataprev.gov.br/sislex/paginas/45/2003/132.htm, viewed on April 7, 2015. |

Additional Resources

| FAO (2012b), “High Food Prices: The Food Security Crisis of 2007–8 and Recent Food Price Increases — Facts and Lessons,” available at http://www.fao.org/fileadmin/user_upload/ISFP/High_food_prices.pdf, viewed on April 7, 2015. | |

| FAO (2012c), “Social Safety Nets and the Food Security Crisis,” available at http://www.fao.org/fileadmin/user_upload/ISFP/Social_safety_nets.pdf, viewed on April 7, 2015. | |

| Plano Brasil Sem Miséria: 1 ano de resultados (Brazil Without Poverty Plan: One-Year Results) (2012), Government of Brazil, available at http://www.mds.gov.br/brasilsemmiseria/arquivos/BSM.pdf, viewed on April 7, 2015. |