ARCHIVE

Vol. 2, No. 2

JULY-DECEMBER, 2012

Research Articles

Research Notes and Statistics

Review Articles

Field Reports

Book Reviews

Land Conflicts and Attacks on Dalits:

A Case Study from a Village in Marathwada, India

R. Ramakumar* and Tushar Kamble†

*Associate Professor, School of Development Studies, Tata Institute of Social Sciences, Mumbai.

†Research Assistant, School of Development Studies, Tata Institute of Social Sciences, Mumbai.

The right to own property is systematically denied to Dalits. Landlessness – encompassing a lack of access to land, inability to own land, and forced evictions – constitutes a crucial element in the subordination of Dalits. When Dalits do acquire land, elements of the right to own property – including the right to access and enjoy it – are routinely infringed (Centre for Human Rights and Global Justice 2007).

In 1996, a nongovernmental organization undertook a door-to-door survey of 250 villages in the state of Gujarat and found that, in almost all villages, those who had title to land had no possession, and those who had possession had not had their land measured or faced illegal encroachments from upper castes (Human Rights Watch 1999).

…the distinction and discrimination based on caste still prevails in Maharashtra. A slight provocation like a dispute at the water pump leads to polarization as Dalits and non-Dalits; non-Dalits attack Dalit bastis, destroy their houses and even kill them…The Dalits are not supposed to assert their rights and equality before the law. If they do, they have to pay a price (PUCL 2003).

Landlessness is a pervasive feature of Dalit households in rural India. Landlessness is foundational to the existence of Dalits as a distinct social group in the rural areas; it forms the material basis for the domination and exploitation of Dalits in the non-economic spheres as well. The caste system thus contains elements of both social oppression and class exploitation.

Caste discrimination has also acquired the status of an ideology. The conception and practice of caste as an ideology implies that a person is primarily perceived by another not on the basis of his or her capabilities, but on the basis of the caste that he or she is born into. In this context, it is no surprise that the efforts of upper caste groups to sustain “cultural differentiations” transgress into the non-cultural spheres, including the economic sphere.1 Thus, even Dalits who own land are subjected to discrimination and harassment by upper caste groups.

This note attempts to verify the hypothesis formulated in the preceding paragraph through a case study of a Dalit household from one village in rural Maharashtra. It is based on repeated visits to the village by the authors in May 2012 and July 2012.

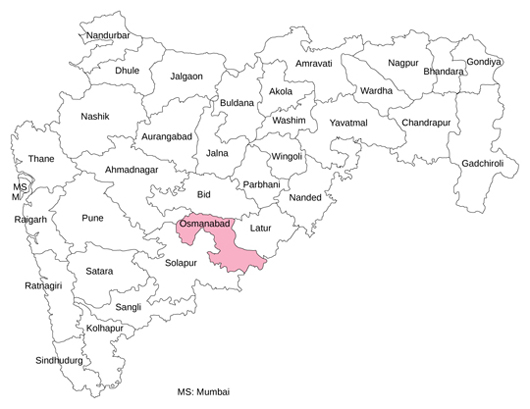

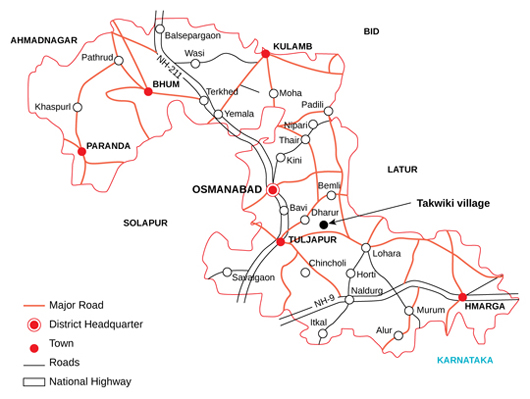

Takwiki is a village in the Osmanabad taluka of the Osmanabad district of Maharashtra (see Figure 1 and 2). The district belongs to the larger Marathwada region, which is a drought-prone region and relatively backward in social and economic indicators. According to the 2001 Census, Takwiki had a total population of 2396 persons, residing in 486 households. About 14 per cent of its population belonged to the Scheduled Castes. The overall literacy rate in the village was 54.5 per cent. Of all main workers in the village, 47 per cent were cultivators and 36 per cent were agricultural labourers.

Source: Adapted from www.mapsofindia.com.

This is a case study of a household headed by Dhondiba Raut. The authors learned of the predicament of this household when a household member approached one of the authors (Ramakumar) of this article for help.

Source: Adapted from www.mapsofindia.com.

The Raut household, belonging to the Chambhar caste, has been living in Takwiki village for more than a century. Until recently, Takwiki and the surrounding villages were dominated by Muslim landlords. The Marathwada drought of 1971-72, and the acute squeeze on incomes that it inflicted on peasants at large, forced some Muslim landlords in the region to sell a part of their land. In consequence, Tulsiram Raut (Dhondiba’s father) purchased 7.5 acres of land in 1972 from Taher Khan Lal Khan Pathan, who owned a large area of land in Takwiki.2 Tulsiram was a cobbler; he used his savings and a loan to purchase the plot at the relatively low cost of Rs 250-500 per acre. While the transfer of land had taken place in 1972 itself, the official transfer of land in the village land records (fer far nondani) took place only in 1979. The 7.5 acres of land were part of Block Number (gut kramank) 133 in the land records. In Block Number 133 in the village map, Tulsiram’s plot formed three pieces of about 4 acres each (see the area with red borders in Figure 3).

Source: Google earth.

Tulsiram had three sons when he purchased the land: Kondiba Tulsiram Raut, Dhondiba Tulsiram Raut, and Vithoba Tulsiram Raut. The land that he purchased was equally divided among the three sons, with one rectangular piece of land going to each. In 2012, all these plots were irrigated by a well dug at the western side of Block Number 133. The Rauts grew sugar cane in these plots.

In 1988, Dhondiba and his brother Vithoba pooled savings and purchased some more land in Takwiki.3 The plots of land newly purchased were geographically fragmented, and a one-acre plot was located just across the eastern bund (marked yellow in Figure 3) of Block Number 133. At the time of purchase, this one-acre plot, belonging to Block Number 132, was registered in the name of Vithoba. In 2007, Vithoba transferred the ownership of this one-acre plot to Dhondiba, in exchange (no extra cash was paid) for another one-acre plot owned by Dhondiba located elsewhere. Thus, Dhondiba came to own the one-acre plot in Block Number 132 from 2007. This plot was valued at between Rs 6 and 8 lakhs in 2012, and was registered in the name of Dhondiba’s wife, Hirabai Raut.

Much of the land in Block Number 132 belonged to the Kedar household, a large landowning upper caste (Maratha) household from Patoda, the village adjacent to Takwiki. According to the residents of Takwiki, the Kedar household owned more than 120 acres of land in 2012. They also leased in large areas of land from others on a long-term basis, about which no estimate was available. Before the 1970s, according to the village people we interviewed, the Kedar household owned only about 10-15 acres of land. In those days, the household mainly ran a tempo-transport business. Being the only tempo-owning household in the region allowed the Kedars to accumulate substantial savings, which were channeled into purchasing land after the 1972 drought. According to some accounts, since the Kedar household members were also the local moneylenders in the 1970s, the widespread default on loans during and after the 1972 drought enabled them to attach additional areas of land. However, it was not possible independently to verify these accounts.

In 2011-12, the Kedar household enjoyed considerable economic clout. They were the largest landowners in Takwiki and Patoda. They owned two tractors, which were partly rented out, a dairy farm, a jaggery-making unit, a timber agency, and an electrical rewinding shop in Patoda and Takwiki. They continued to own tempo vans, which plied on rent, and involve themselves in moneylending. Many Takwiki villagers assert that with all this clout, the Kedar household effectively had the right of first refusal in any land transaction that took place in the region. They cited a number of cases where the Kedar household bid up the land price to such high levels that no one else stood a chance of buying the land going on sale.

Politically, the Kedar household attached itself to the Nationalist Congress Party (NCP) in the region and generally enjoyed a close relationship with the party’s district leadership. Members of the Kedar household were also regularly chosen as members on the gram panchayat as well as the boards of the local credit societies in Patoda.4

The one-acre plot that Dhondiba had swapped with Vithoba in 2007 was located within a series of land plots owned by the Kedar household beyond the eastern bund of Block Number 133 (these plots belong, according to the village land records, to Block Numbers 126, 130, 131, 134, 135, 147, 149, 150, 151, 155, 156, 157, 167, and so on). If the Kedar household were to annex the one-acre plot owned by Dhondiba, the advantages would be many. First, they would get to own a large piece of contiguous land area totally under their possession on the eastern side of the bund. In fact, the Kedar household had made an offer to Dhondiba in 2011 to buy out all his land, including the one-acre plot, but Dhondiba had refused; the convenience of owning all his land at one place was paramount for him too. Secondly, the newly established dairy farm and the jaggery-making unit of Kedar household were situated close to Dhondiba’s plot. If the Kedars possessed this plot, they could build a direct approach road to these units; in the absence of it, they were obliged to reach these units over a longer route from the Patoda village.

While the economic advantages of taking Dhondiba’s land were substantial for the Kedars, another dimension was too evident to be missed. Dhondiba was a Chambhar, who owned an irrigated plot cultivated with sugar cane right under the nose of the powerful Maratha household. Apparently, the Kedars believed that their social prestige was lowered by the Dalit ownership of the plot in their midst. Getting rid of the Dalit from the plot would thus raise the social prestige of the Kedar household.

When efforts to persuade Dhondiba to sell the plot failed, encroachment began.5 From the beginning of 2011, the Kedars began to drive tractors and tempos through Dhondiba’s plot to travel to their dairy farm and jaggery-making unit. In Figure 4, this encroachment is depicted pictorially; it was in the form of driving from Point A to Point B, and then proceeding to Point C. The objective, according to the Raut household, was constantly to harass them to the point of forcing them to sell the land to the Kedars and move out.

Figure 4 Aerial photograph of the disputed land plots with the nature of encroachment, Takwiki village, Maharashtra, 2012

Source: Google earth.

After tolerating the encroachment for a few days, Dhondiba’s son, Bharat Raut, confronted some of the Kedars and asked them to stop driving through their plot. However, Bharat was greeted with a flurry of abuse, including the use of caste names.6 The caste dimension of the encroachment now came out into the open. According to Bharat, some of the abusive language went like this:

“हे चाम्भारड्या, तुम्हाला शेताची काय गरज आहे? खेतर शिवून खाणारी जात तुमची” (You Chambhar, what business do you have in farming? Your caste is to work with animal skin).

“हे चाम्भारड्या, मस्ती चढली आहे का तुला? तुम्ही चांभार हे शेत कसे कसता आम्ही पाहून घेऊ” (You Chambhars appear to be enjoying [cultivation]. We will see how you Chambhars cultivate this land).

Bharat says he was afraid to approach the police at this stage. The encroachment continued on a regular basis after this incident. A few days later, while the Kedars were driving through the plot, they ran the tractor over the irrigation pipeline on the eastern side of Kondiba Raut’s plot.7 The pipeline was destroyed. Kondiba confronted the Kedars over this action. The reaction from members of the dominant household, according to a police complaint filed by Kondiba, was to hurl abuse at him with caste names and severely assault him with wooden sticks.

Deciding that enough was enough, Kondiba and Bharat approached the Bembili police station to file a complaint under The Scheduled Castes and The Scheduled Tribes (Prevention of Atrocities) Act, 1989 (henceforth, Atrocities Act). In the beginning, the Head Constable at the police station (the exact date is not available) refused even to accept the complaint from Kondiba and Bharat.8 However, forced by Bharat’s insistence, the police accepted their complaint on a piece of paper. Kondiba’s statement was recorded and he was asked to leave. Bharat insisted on filing the case under the Atrocities Act. But the Head Constable at the police station refused and told him: “All that cannot be done. You do not know what the Atrocities Act is. This incident does not fall under its purview.”9

The next day, Bharat went to the police station and demanded to be shown the statements recorded the previous day. The demand was first refused, but eventually he was given a duplicate copy of the FIR. To his surprise, Bharat found that Kondiba’s statement was recorded incompletely: only the instance of physical attack was recorded, and there was no mention of the verbal abuse using caste names.10 Evidently, the statement was recorded in such a way that no complaint could be filed under the Atrocities Act. Kondiba’s complaint was being considered a non-cognizable offence.

For more than two weeks after the attack, no action was taken on the complaint filed by Bharat. No arrests were made, and there was no questioning of the Kedars. On the 29th of January 2011, Dhondiba’s younger son, Karan Raut, approached the police station to press for lodging the complaint under the Atrocities Act. Karan was also told that no case under the Atrocities Act could be registered against the Kedars for several reasons.11 First, he was told, land encroachment issues did not fall under the purview of the Atrocities Act: “this is a civil case, we cannot register the case as a criminal offence.” Secondly, special permission was required from the Superintendent of Police (SP) of the district to file such a case. Thirdly, a person from the caste of the accused persons (that is, a person from the Maratha caste) was to present himself as a witness for such a case to be filed under the Atrocities Act.

Every reason cited for not registering a case under the Atrocities Act was wrong.12 First, the Atrocities Act clearly states in Chapter II that the list of offences under the Act includes “whoever, not being a member of a Scheduled Caste or a Scheduled Tribe… wrongfully dispossesses a member of a Scheduled Caste or a Scheduled Tribe from his land or premises or interferes with the enjoyment of his rights over any land, premises or water.” The Act also clearly states that offences are to be treated as criminal, under the Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973. Secondly, no permission from the SP is required to register a case under the Atrocities Act. According to the guidelines, a case can be independently registered at the local police station; after registering the case, the investigation has to be handed over to an officer not below the level of a Deputy Superintendent of Police (DySP). Thirdly, the caste of the witness is nowhere a consideration under the Atrocities Act.

The absence of police action further encouraged the Kedar household to proceed with aggressive encroachment. On the 18th of January 2011, according to a complaint filed by Bharat Raut at the Bembili police station, four brothers of the Kedar household reached Dhondiba’s plot with a bulldozer. Coming in from the northern end of Dhondiba’s plot (Point A in Figure 4), they first leveled the bund on the eastern side of Block Number 133. After leveling the bund, they encroached about 10 feet into Dhondiba’s plot and cleared the land for a road on its western side (from Point A to Point B; north to south) and then, bending eastward, on the southern side (from Point B to Point C; west to east). The levelling ended once the encroached pathway reached Kedar household’s jaggery-making unit (Point D in Figure 4). During the encroachment, the Kedars broke Dhondiba’s irrigation pipeline and threw it away to one side. A tree that stood on the bund was also felled.

Photographs of the encroachment were taken by Dhondiba’s family the same day; one of these, given to us by Bharat, is presented as Exhibit 1. The photographs show that the newly built road was wide enough to allow a truck or tempo van or a tractor to pass through.

That very night, Bharat went to the Kedars to question their latest act of violent and lawless encroachment.13 However, according to Bharat, he was again abused with caste names and threatened with dire consequences if he resisted further.

Faced with encroachment and regular threats to life, Dhondiba and Bharat approached the court of the Taluk Judicial Magistrate (First Class) for justice. The court, on March 10, 2011, stayed the encroachment and restrained the Kedar household from using the newly built pathway. Dhondiba Raut was to collect the official stay order after two days.14

Confident of their rights over the plot, Hirabai and Bharat went to work on the land on the morning of March 11, 2011.15 What greeted them was a shower of abuse and a violent physical attack. Angry over Dhondiba’s victory in the court of the Taluk Judicial Magistrate (First Class), members of the Kedar household came in with wooden poles and began to hit Hirabai and Bharat. Hirabai was hit on the back of her head, leaving her bleeding. Bharat was beaten up by more than one person for over 10 minutes, and suffered a fracture of his left arm and bruises all over his body.

Throughout the physical attack, the Kedars also abused Hirabai and Bharat severely, using caste names.16 For instance, Bharat was told through the attack: “हे चाम्भारड्या, असले स्टे मी बांधून हिंडतो” (“You Chambhar, we wear such stay orders like a garland and roam around”).

Bleeding profusely, Hirabai and Bharat rushed to the Bembili police station to file a complaint. However, the Assistant Police Inspector refused to accept a formal complaint against the Kedar household.17 Instead, they asked Hirabai and Bharat to go to the hospital and get treated. Bharat had no choice but to agree, as his mother was bleeding. They went to the Primary Health Centre at Bembili village, from where they were referred to the Civil Hospital, Osmanabad. At the Civil Hospital, they were admitted the same day.

The next day Bharat got himself discharged, went to the court of the Taluk Judicial Magistrate (First Class), and obtained an official copy of the order staying the encroachment. Armed with a copy of the court order, Bharat approached the Bembili police station once again. Once again, the police refused to consider Bharat’s complaint under the Atrocities Act. Just as Kondiba was told in January 2011, Bharat was informed that the attack on him did not come under the purview of the Atrocities Act. His complaint too was being treated as a normal case of alleged assault.18

The attack on Hirabai and Bharat was not without witnesses. Razak Pathan, a middle peasant who owned a plot of land close to Dhondiba’s, was a witness to the attack on Hirabai and Bharat on March 11th. Razak Pathan’s name was specifically cited in Bharat’s police complaint at a witness, and he personally appeared at the police station to give a statement against the Kedars. Razak Pathan’s son, Imran Pathan, was the police patil of Takwiki village. Yet the Pathan family faced a severe backlash from the Kedar household. According to Imran, his father was first asked by the Kedars to withdraw the statement given to the police: “Why are you interfering in favour of the Chambhars?” Razak Pathan was asked.19 Imran told us in an interview that his family decided to stick to their statement because “If it is the Rauts today, tomorrow it may be us. So we have to unitedly move against this big landlord. Otherwise, he will eat us all one day.”20

When Razak Pathan refused to withdraw his statement, it was his family’s turn to face harassment.21 First, according to Imran, the Kedars arranged to send a complaint to the District Collector demanding the removal of Imran as the police patil. When Imran came to know of the complaint, he approached every village person whose signature appeared in the complaint. All of them denied having ever signed such a complaint; it turned out that the complaint contained forged signatures. But that was not all. The approach to Razak Pathan’s plot of land passed through the bunds of a few plots owned by the Kedar household. Razak Pathan used to take a tractor and other implements to his field through this rather wide bund. Soon after the incident, the Kedars closed down this path by fencing it off (a photograph of the fence is given as Exhibit 2). The Pathans had to travel to their field by taking another road, which meant a detour of about one km. “What to do?” Imran said dejectedly when we spoke to him.22

With the matter reaching a dead end, Karan Raut decided to take external help. He brought the matter to the notice of a few leaders of the All India Kisan Sabha in Solapur and a leading journalist based in Mumbai. The journalist spoke personally to the District Collector, who promised swift action on the case. Karan sent a direct complaint to the Collector by email, of which we have a copy. Based on the email, the Collector, a Dalit himself, instructed the Superintendent of Police of the district to file a case under the Atrocities Act. On the Superintendent’s orders, a case was finally filed under the Atrocities Act at the Bembili police station. A Deputy Superintendent of Police visited the village and the encroached land, as per the requirements, and took the statements of all concerned. Further, two officials from the State Social Welfare department visited Dhondiba’s house and recorded their statements.23

Just as it appeared that some positive action was forthcoming, the Assistant Police Inspector and the Head Constable at the local police station began to intervene again in favour of the Kedars. According to a complaint letter written by Karan to the District Collector, The day after the visit of the Deputy Superintendent to the village,

…my brother and mother were called to the Police Station. At the Police Station, a constable, in the absence of an officer, tried to record a statement of my mother that suggested that we would appeal in the court, though in the meantime would allow the Kedar family to use the road illegally constructed across our field. We refused to sign the statement. [email to Mr Pravin Gedam, District Collector, Osmanabad dated 9th April 2011]

Even after the visit of the Deputy Superintendent and the government officials to the village, no arrests were made. Dhondiba Raut’s family sent another complaint to the Collector, and managed to get the supporting journalist to speak to the Collector once again. Finally, on repeated orders from the Collector and the Superintendent of Police, an arrest warrant was issued in the names of the four accused members of the Kedar household. Now facing heat, the four accused members of the Kedar household absconded. After about 20 days in hiding, they appeared in the court of the Taluk Judicial Magistrate (First Class) to surrender, but the police recorded their arrest before they could surrender. The accused remained in custody for about 18 days. After 18 days in custody, the court granted them bail. At the time of writing this note, the arrested members of the Kedar family were in Takwiki village itself. No further action was taken from the side of the police, and it appeared that the case would drag on. There has been no further hearing in the case.

But if anyone thought that the arrests would restrain the Kedars from harassing the Raut family any further, they were mistaken. According to Bharat, there was no end to the harassment even after the arrests. In fact, the acts of distressing oppression extended from farm to home, and were continuing at the time of writing this note.

First, according to Bharat, there were continuing efforts to harass him on the farm by trying to divert surplus water into his field.24 Topographically, the fields of the Kedar household were at an elevation from where excess water drained down through a canal by the side of Dhondiba’s fields. After the arrests, the Kedars had reduced the height of the bund that separated the plots of the Kedars and the Rauts. As a result, excess water, instead of flowing into the canal by the side, spilled over the bund and flowed into the plots owned by the Rauts. According to Bharat, this presented a constant threat to their standing crop of sugar cane.

Secondly, going by informally laid-out village rules, all plots of land lying within the boundaries of one village should be reachable by a pathway that originates from the same village. In Takwiki, these pathways were roughly about 7 feet wide. While laying such pathways, an equal extent of land (i.e., 3.5 feet each) was to be given away by every landowner whose land lay on the way. The village road from Takwiki (marked as an orange line in Figure 3) was constructed by acquiring 3.5 feet each from the plots of the Rauts (on the northern side) and the Kedars (on the southern side). However, after the conflict, the Kedar household recaptured their share of 3.5 feet of the road and began to insist with the panchayat that if a road had to be built, all 7 feet had to be acquired from the plot of the Rauts. According to Bharat, there was constant tension in the field after this act by the Kedars.25

The Rauts were also subjected to new forms of harassment inside the village residential area. Bharat alleged that a tough, with criminal antecedents, had been contracted to harass his family inside the village.26 Widely known and feared for his thuggish acts, including his alleged recent involvement in a case of burning the house of a Pardhi household, this man, who had no locus standi in the matter, had begun to threaten Dhondiba and Bharat and ask them to vacate the concerned plot to the Kedars.

The threats aside, according to Bharat, the tough was harassing the Raut family in less direct ways.27 First, there was a common village plot that the Raut family has used for many years as a dumping ground for garbage. However, according to Bharat, the tough had recently fenced off that land for himself, and prevented the Rauts from dropping garbage there. Secondly, there was a well in a vacant and commonly held plot that the Rauts used to draw water. More recently, according to Bharat, the tough had fenced off that plot of land too, claiming he had leased it in from the government.

The nature and pattern of these acts led the Raut household to conclude that the tough was unleashed on them by some members of the Kedar household. According to Bharat, a member of the Kedar household had told him, in a recent threatening conversation, that “10 एक्कर जमीन गेली तरी हरकत नाही, पण तुला जीवंथ सोडणार नाही” (“even if we lose 10 acres of land, it does not matter; we will not leave you till you die”).28 Bharat and other villagers have reasonably interpreted this threat as implying an instruction to the tough not to worry about the consequences of physically harming Dhondiba or Bharat, and that they were ready to spend an equivalent of the value of 10 acres of land (about Rs 30-40 lakhs) on the cases that might follow.

The oppression of the Raut household shares elements of one of the most gruesome cases of caste-related violence in recent times: the Khairlanji massacre on the September 29, 2006, in the Bhandara district of Maharashtra. On that day, four members of the family of Bhaiyalal Bhotmange (belonging to the Dalit community) were brutally murdered by an upper-caste Hindu mob in the Khairlanji village (for reports on the massacre, see Dhawale 2006 and Teltumbde 2007). There again, it was encroachment into the land owned by the Bhotmange family that culminated in the killings. Dhawale (2006) notes that the “the immediate cause of the massacre” was that “whatever little land they had was also sought to be taken away from them.” According to Teltumbde (2007), “the dispute over the passage through Bhotmange land provided a backdrop to the incident.” Teltumbde further notes:

The land, which was used as a common passage by the villagers as long as it was uncultivated, became unavailable to villagers [after the Bhotmange household purchased it for cultivation]. The matter had gone to revenue court, but eventually Bhaiyalal Bhotmange emerged unscathed…The injury to the caste pride of the caste Hindus simmered and grew with the increasing assertiveness of Bhotmanges, which was perceived to be partly due to their upward economic mobility and cultural progress, the latter in terms of the educational achievements of the Bhotmange children…While the origin of dispute thus appears to be land, the caste prejudice of the caste Hindu villagers played a major role, right from the articulation of dispute through the development and eventual precipitation in to a heinous crime (2007, p. 1019).

Basing his argument on different cases of atrocities on Dalits in Maharashtra, including Khairlanji, Teltumbde argues that the most important problem is the “complicity of the state machinery.”

…the record of atrocities on Dalits reflects the utter failure of the state in the discharge of its constitutional responsibility…The state’s complicity has manifested even in its post-atrocity dealings in refusing to register the case, or, if registered, in not conducting proper investigation, and thereby weakening the case in the court of law…The very process of Dalits registering a crime with the police is fraught with hurdles…The case gets counted in the statistics of crimes against SCs only after it gets past these hurdles. More often than not, the local police clearly take sides with the perpetrators of the crime against the Dalit victims and do everything possible to suppress the crime at the first instance…Even if the crime is registered, it is the police who investigate the crime and collect evidence for prosecution. The shoddy investigation by the police in such cases is legion, as evidenced by the extremely paltry rate of conviction. There is a tacit assurance to the upper castes that the official protectors of the law would not come in their way in their dealings with Dalits. This assurance has played a key role in sustaining the growth of atrocities year after year (2007, p. 1020).

The case of the Raut household studied here exemplifies each of the hurdles that Teltumbde lists.29 The harassment of the household is a continuing one, and though it has not yet grown into the extreme form of violence inflicted on the Bhotmange household, the commonalities in the methods of oppression are revealing.

In May 2012, when we interviewed members of the Raut household, they were living a life of fear and growing stress. They had fought oppression bravely, resorting to nothing but the law and claiming what was theirs by right. But even Bharat appeared to be tired of fighting the case. He told us:

In the field, Kedar harasses us. At home, [the tough] harasses us. We live our lives to be happy and joyous. But there has been no happiness or joy in my life for about two years now. At the same time, I cannot sell all my land and go away. That is exactly what the Kedars want me to do, and I will not let them win this game. However, I will not deny that I often have doubts about what to do.30

Keywords: Dalit households, rural Maharashtra, Scheduled Caste and Scheduled Tribe (Prevention of Atrocities) Act.

Notes

1 As Guru (2012) notes on the caste system in India, “cultural difference may subsume within itself elements of both material and social hierarchy.” In the Marxist literature, there is appreciation of what Hobsbawm (2011) calls the “relative autonomy of…super-structural elements” in the evolution of society. In his famous letter to Mehring in 1893, Frederick Engels criticized the argument that “ideological spheres” do not have “independent historical development” or “any effect upon history.” Engels wrote that “the basis of this is the common undialectical conception of cause and effect as rigidly opposite poles, the total disregarding of interaction; these gentlemen often almost deliberately forget that once an historic element has been brought into the world by other elements, ultimately by economic facts, it also reacts in its turn and may react on its environment and even on its own causes” (Engels 1893, emphasis added).

12 Interview, Uddhav Kamble, Formerly Special Inspector General of Police (Protection of Civil Rights), Maharashtra, July 2012.

28 Interview, Bharat Raut, July 2012. There are similarities between this statement from the Kedar household and the statements of upper caste landlords in other States. In a recent article in Indian Express, a land surveyor in Siwan in Bihar reports a quote from an upper caste landlord illegally holding Bhoodan land thus: “When we are born, our parents keep a big bundle of currency notes wrapped in a red cloth so that we are able to fight land-related cases” (Singh 2012).

29 For Maharashtra as a whole, there were 304 cases registered under the Atrocities Act in 2011 (NCRB 2012). According to a news report in 2010, “Maharashtra’s conviction rate in caste atrocity cases is one of the lowest in India”. For the year 2007, the share of convictions in offences against the SCs was 2.9 per cent only. This share had declined between 2005 and 2007, from 6.3 per cent to 2.9 per cent.

References

| Centre for Human Rights and Global Justice (2007), Hidden Apartheid, NYU School of Law and Human Rights Watch, New Delhi. | |

| Dhawale, Ashok (2006), “The Khairlanji Massacre and after,” People’s Democracy, December 10. | |

| Engels, Frederick (1893), “Engels to Franz Mehring,” in Marx and Engels Correspondence, International Publishers, London, available at http://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1893/letters/93_07_14.htm, viewed on July 5, 2012. | |

| Gaikwad, Rahi (2010), “Maharashtra’s Record in Conviction Rate in Caste Atrocity Cases Dismal,” The Hindu, June 20. | |

| Guru, Gopal (2012), “Conversation on Caste Today,” Seminar, issue 633, May. | |

| Hobsbawm, Eric (2011), How to Change the World: Reflections on Marx and Marxism, Abacus, London. | |

| Human Rights Watch (1999), Broken People: Caste Violence Against India’s Untouchables, New York, available at http://www.hrw.org/reports/1999/india/index.htm, viewed on July 5, 2012. | |

| National Crime Records Bureau (2012), Crime in India 2011, Ministry of Home, New Delhi. | |

| People’s Union for Civil Liberties (PUCL) (2003), “The Caste Cauldron of Maharashtra,” A Report by the Fact Finding Team, Mumbai, November. | |

| Singh, Santosh (2012), “No Half Measures,” Indian Express, July 8. | |

| Teltumbde, Anand (2007), “Khairlanji and Its Aftermath: Exploding Some Myths,” Economic and Political Weekly, vol. 35, no. 12, March 24. |

Exhibit 1 Photograph of the encroachment into Dhondiba Raut’s plot, taken in 2001 from near Point B in Figure 3, facing Point C

Photograph courtesy: Bharat Raut