ARCHIVE

Vol. 2, No. 1

JANUARY-JUNE, 2012

Research Articles

Research Notes and Statistics

Special Essay

Field Reports

Book Reviews

Land Reform and Rural Livelihood in South Africa:

Does Access to Land Matter?

Horman Chitonge* and Lungisile Ntsebeza†

*Centre for African Studies, University of Cape Town, horman.chitonge@uct.ac.za.

†Centre for African Studies, University of Cape Town, lntsebeza@gmail.com.

Abstract: This paper presents the main findings of a study conducted in 2009 and 2010 of land redistribution projects in the Chris Hani District Municipality (CHDM), focusing on the question of whether land transferred through the land reform programme in South Africa is making a contribution to improving the livelihoods of beneficiaries. The paper highlights three main findings of this study. First, the acquisition of land has improved, in some cases vastly, the socio-economic conditions of beneficiaries. Secondly, land reform beneficiary households and those who acquired land on their own in commercial farm areas are far better off (on average) than their counterparts in the communal areas, who have limited access to land. Thirdly, most land reform beneficiaries are able to improve their livelihoods with very limited or, in many instances, no support from the state. These findings contradict the gloomy picture painted by most studies on land reform and livelihoods, as well as recent pronouncements by some senior government officials and analysts that land transferred through land reform is not improving the livelihoods of beneficiaries, that it is not being used, and that black Africans are no longer interested in land as a means of livelihood.

Keywords: access to land, land reform, beneficiaries, non-beneficiaries, livelihoods.

Introduction

This paper focuses on the critical question of whether or not holdings of land, including by beneficiaries of the land reform programme in South Africa, contribute towards improving the livelihoods of landholders.1 We look at the contribution of landholding in general, and land gained through land reform in particular, to livelihoods. Understanding the role that land plays in the livelihoods of beneficiaries of land reform provides information and lessons not only on how they use the land, but also on how to improve the formulation and implementation of future land reform programmes. Land reform has assumed critical importance under President Zuma’s administration, which puts rural development as one of its top priorities. In this paper, the benefits of holding land is not restricted to quantifiable monetary or other improvements, but is taken to include qualitative gains, such as an enhanced sense of justice, self-esteem, security, dignity, and self-respect, as well.

Land

Reform Programmes and Rural Livelihoods:

The Background

The land reform programme in South Africa must be viewed against the backdrop of attempts by the African National Congress (ANC)-led Government of National Unity (GNU) to address the painful colonial and apartheid legacy of land dispossession and overcrowding experienced by the African people in particular (DLA 1997, p. 7). Land reform was introduced soon after the landslide victory of the ANC in the first democratic elections in 1994. In its election manifesto, the Reconstruction and Development Programme (RDP), the ANC identified land reform as key to rural development. Land reform entailed the provision of “residential and productive land to the poorest section of the rural population and aspirant farmers” (ANC 1994, p. 20). Building on these views, the White Paper on Land Policy saw land reform as “a cornerstone for reconstruction and development,” and argued that “a land policy for the country needs to deal effectively with: the injustices of racially based land dispossession of the past; the need for a more equitable distribution of land ownership; the need for land reform to reduce poverty and contribute to economic growth” (DLA 1997, p. 1).

Land reform in post-apartheid South Africa has three components: land restitution, land redistribution, and land tenure reform, all based on Section 25 (5), (6), and (7) of the South African Constitution of 1996. The land policy that evolved promised, inter alia, that land would be made available to the land-needy, including people residing in communal areas. The target of the land reform programme in the initial period, that is, between 1994 and 1999, was poor households that earned R1,500 per month or less. Each household was to be given a grant of R15,000 (later increased to R16,000). However, given the fact that land reform in South Africa is market-led, it required a number of households to be put together into groups in order to meet the price of commercial farms, a phenomenon that some scholars have referred to as a “rent-a-crowd syndrome” (Hall 2009, p. 179 and Hall and Cliffe 2009, p. 5–7).

In 2001, following a review of the Settlement/Land Acquisition Grant (SLAG), a new approach to land reform was introduced in the form of the Land Redistribution for Agricultural Development (LRAD) sub-programme. It was stated that “beneficiaries can access grants under LRAD on a sliding scale, depending on the amount of their own contribution” (DLA 2001, p. 4). However, as with SLAG, most aspirant beneficiaries could not afford to buy farms individually and ended up forming groups to increase the “own contribution” that determined the size of grant a beneficiary received. The LRAD sub-programme targeted individuals, unlike SLAG which gave grants to households. This led some scholars to conclude that the sub-programme aimed at creating a class of black farmers at the expense of the poor (Ntsebeza and Hendricks 2000 and Hall and Ntsebeza 2007).

The Debates on Land Reform

Debates on land reform in South Africa, particularly in the first decade of South Africa’s democracy, focused on the pace of delivery of land promised in the land reform programme (Ntsebeza and Hall 2007, Lahiff 2008, and Hendricks and Ntsebeza 2010). The overall conclusion was that the pace was painfully slow. The initial target of land reform was that 30 per cent of agricultural land would be transferred to black Africans by 1999, a date later changed to 2014. Despite this change, the ANC-led government is struggling to meet even this conservative target. Table 1 shows that, by the end of 2009–10, a total of 6.8 million hectares of land had been delivered through the three components of the land reform programme. This represents 26.9 per cent of the targeted 25.5 million hectares (30 per cent of arable land) to be delivered by 2014.

Table 1 Land redistributed in South Africa through land reform programmes, 1995–2010

|

Year |

Red & Tena (hectares) |

Restitution (hectares) |

Total (hectares) |

Total as % of target |

Red & Tena as % of target |

Restitution as % of target |

|

1995–2008 |

2748766.0 |

2265798 |

5014564 |

19.9 |

10.9 |

8.9 |

|

2007/08 |

346011.5 |

432226 |

778238 |

|||

|

2008/09 |

443600.5 |

394755 |

838356 |

|||

|

2009/10 |

239990.5 |

145498 |

385489 |

|||

|

1995–2010 |

3562378.0 |

3238277 |

6800656 |

26.9 |

14.2 |

12.7 |

Note: These figures are

based on the Annual Reports of the Department of Rural Development and Land

Reform (DRDLR), and are not independently verified.

a Red=land

redistribution programme; Ten=tenure reform programme. The figures are for the

combined programmes of land redistribution and tenure reform (these are

reported together).

Source: Annual Reports of the Department of Rural Development and Land Reform (DLA 2009 and DRDLR 2010, 2011).

The literature on the impact of land reform on the livelihoods of beneficiaries falls into two broad categories. There are those who argue that years of land dispossession and proletarianisation have transformed the lifestyle of indigenous people such that they are concerned more with non-farm wage employment than with making a living out of land. The Centre for Development Enterprise (CDE) is the most prominent and consistent proponent of this line of thinking: “Far fewer black South Africans want to farm than is commonly supposed; most blacks regard jobs and housing in urban areas as more important priorities. A national survey commissioned by CDE shows that “only 9 per cent of black people who are currently not farmers have clear farming aspirations” (CDE 2005, p. 14). A later CDE study suggested that land reform wastes productive land: “In many cases, productive land has stayed unoccupied for a year or more after DLA [Department of Land Affairs] acquisition. As a result, formerly high-quality land loses much of its value and productive potential” (CDE 2008, p. 14).

This view has been supported by claims in the media that black South Africans are no longer interested in land as a source of livelihood. Makhanya, former editor of the Sunday Times (South Africa), argued that people need jobs, not land, and that the notion of land redistribution has been based on the “myth that there is a land-hungry mass out there dying to get its hands on a piece of soil. South Africans have very little interest in land” (Makhanya 2009). Additionally, since 2008, senior government officials, including ministers in charge of the Department of Rural Development and Land Reform (DRDLR, formerly the Department of Land Affairs or DLA), have repeatedly stated that over 90 per cent of the land transferred through the land reform programme is not productive (Nkwinti 2010a, 2010b, Phaahla 2010, and Hofstatter 2009). It has never been clear, however, on what basis these claims were made, and what criteria were used to measure success or failure with respect to transferred land.

The claim that jobs in the urban sector are the solution to South Africa’s problem of high rates of poverty and inequality has been made, ironically, at a time when unemployment has been running very high, with almost 40 per cent of the economically active population reportedly unable to find employment.2

The second broad stream in the debate is critical of the CDE position and takes note of the importance of land in improving the livelihoods of the rural people. While those who argue this way also believe that land reform has not improved the quality of life of the beneficiaries, they seek to explain why this is so, rather than draw the conclusion that the beneficiaries of land reform are not interested in land. Overall, these scholars are critical of the manner in which the South African land reform programme has been conceptualised and is being implemented (see Lahiff 2008, pp. 31–32). A significant part of this research has been conducted in Limpopo province.

At the heart of the critique of the land reform programme is its inflexibility with respect to the sub-division of commercial farms. The grant structure of both SLAG and the LRAD sub-programme forces beneficiaries to acquire land as groups. In some – perhaps most – cases the beneficiaries would not have known each other or worked together previously. Aliber et al. (2011) found that, in some instances, farmers who were desperate to sell land collaborated with estate agents, and hastily put together groups of farm workers and people from neighbouring areas. This is a sure recipe for conflict and does not make for good farm management.

Hall (2009, p. 26) has identified two broad categories of group-based farming. The first is “group-based ownership and production,” involving “not only joint ownership of the land but also the pooling of assets and labour.” The second category entails joint ownership of land with production occurring at the household level (ibid., pp. 26–27). Drawing from her research, she comes to the conclusion that the former category is more problematic than the latter. An earlier study conducted in Limpopo came to a similar conclusion, and had argued strongly for the “sub-division of land (even informal sub-division) and individualisation of agricultural production” (Lahiff 2007, p. 8).

Inadequate support for beneficiaries of land reform has also been identified as a major reason for the perceived failure of land reform projects (Hall and Cliffe 2009, p. 2). Hall and Cliffe have further observed that even where support has been given it has been problematic, in the sense that “business planning processes of commercial and capital-intensive production models inappropriate to the needs and capabilities of beneficiaries” have been imposed (ibid.).

While the studies cited above paint a bleak picture of the contribution of land reform to rural livelihoods, there are studies that have more positive conclusions (see, for example, Deininger and May 2000, May and Roberts 2000, May et al. 2002, Eastwood, Kirsten, and Lipton 2006, and Keswell, Carter, and Deininger 2009). Comparing the mean per capita expenditure of households that participated in the land reform programme and those that did not, Keswell, Carter, and Deininger (2009, p. 3) conclude that “the impact of the current programme of redistribution on household per capita consumption is positive, and remains positive and significant even when we have controlled for selection bias.” Other studies show that although the poverty head-count ratio of poverty is generally higher in rural areas than in urban areas, the incidence of poverty is highest among rural households without access to land (Carter and May 1997 and Deininger and May 2000). Related studies have also found that having access to land not only improves access to productive assets, but also generates sustainable livelihoods (CASE 2006 and HSRC 2003).

Research Design and Methodology

The origins of the study on which this paper is based can be traced to 2008, when the Cala University Student Association (CALUSA), an NGO (based at Cala in the Eastern Cape) that focuses on land questions in the Chris Hani District Municipality (CHDM), and the National Research Foundation (NRF) Research Chair in Land Reform and Democracy in South Africa at the University of Cape Town agreed to collaborate on a longitudinal study of what beneficiaries do with the land they receive through the land reform programme, and whether having access to land makes a difference to their lives.

In the first phase of that study, data were collected using the participatory poverty assessment (PPA) techniques. Land reform projects that were included in the study were drawn from a pool of projects that CALUSA and the Research Chair assessed in 2008. Particular attention was given to choose projects that were deemed to be very successful and those with no progress at all. A total of nine projects were chosen. The PPAs involved mapping of land, transect walks to identify land, wealth ranking, and making timelines of the livelihoods of beneficiary households.

In the second phase, data were collected through a census of all beneficiary households of the chosen projects, and of a selected group of non-beneficiary households with similar livelihood strategies and from the same areas where the land reform beneficiaries resided prior to getting land.

Sampling

Land Reform Beneficiary Households

It is noteworthy that the Department of Rural Development and Land Reform (DRDLR) list recorded individual members of projects and not households. This was mainly because the LRAD sub-programme, which the study focused on, targeted individuals and not households. In most cases, two or more members of a project belonged to the same household (often husband and wife). In some cases, the initial number of beneficiaries and households has declined due to death or conflict within the groups (see Anseeuw and Mathebula 2008, p. 38, and Aliber et al. 2011, p. 69, for experiences in Limpopo province). The census of beneficiary households covered all households that included at least one individual beneficiary.

In order to ensure that the beneficiary and non-beneficiary households were as comparable as possible, the non-beneficiary group was constituted by selecting households with similar livelihood strategies and from the same areas where the beneficiaries resided prior to getting land. Additionally, the non-beneficiary household had to be directly involved in land as the main source of livelihood or express interest in pursuing land-based livelihood if land was made available. Most of the non-beneficiary households included in the study had, with assistance from CALUSA, actually applied for land but had not received it, mainly because the slow pace of land redistribution in South Africa as outlined above.

Selecting non-beneficiaries from the same local environment as the beneficiaries increased the likelihood of a beneficiary and non-beneficiary household having similar livelihoods before and after the transfer of land. At the same time, households in communal areas are not homogenous. Also, despite having been selected from the same locality, there is a possibility that the differences between the two groups are on account of different initial conditions and other unobserved differences. In view of this, the differences observed between the groups should be cautiously interpreted.

Data were collected from a total of 255 households (99 beneficiary households and 156 non-beneficiary households), adding up to 1,457 persons. The questionnaire used to collect data at the household level included questions on household size, consumption/expenditure, landholding, agricultural production (mainly livestock and crops), labour supply, private and public remittances, agricultural support services, general public services, and non-agricultural activities. Since the study sought to establish the possible contribution of land to livelihood, the household was adopted as a unit of data collection and analysis, for the reason that the contribution that land makes is more aptly captured at the household level.

Using the household as the unit of analysis distinguishes this study from many land reform case studies which have evaluated projects and not households (see, for example, Aliber et al. 2011, and Anseeuw and Mathebula 2008). Focusing on households makes it possible to capture even the smallest contribution, which may be missed at the project level. Further, in trying to assess whether land makes any contribution to the livelihood of households, information on total production in the household (for sale and for own consumption) was collected and used to estimate gross household income.

As illustrated in Table 3 below, the majority of non-beneficiary households own plots of land in communal areas that are similar to plots owned by land beneficiaries before receiving land. The non-beneficiary households comprise four main groups according to the way they gained access to land. First, there are households that gained land by buying plots of land outside the state’s land reform programme; these are classified as “bought.” Secondly, some households have access to land inherited from deceased relatives, mainly in the former reserve areas. These households are referred to here as “inherited.” Thirdly, some households were allocated land by traditional authorities (usually the chief or village headman) in areas under these authorities. These are referred to as “chiefs”. Fourthly, there are households that do not own a plot of their own, though they may have access to common grazing land. These are referred to as “no land.”

Table 2 below shows that the majority (76 per cent) of households remained in the residences they had occupied before receiving land, and that most of them were still using the small plots of land they had before acquiring land through land reform. This suggests that, contrary to one of the objectives of land redistribution programme, the impact of redistribution on decongestion of the communal areas was small.3

Table 2 Location of residences of beneficiary and non-beneficiary households after land acquisition, 2010

|

Beneficiary |

Non-beneficiary |

|||

|

Number |

% |

Number |

% |

|

|

Remained in same residence |

75 |

76.2 |

141 |

85.5 |

|

Moved to acquired land |

10 |

11.0 |

3 |

2.0 |

|

Family relocated |

7 |

7.2 |

11 |

6.5 |

|

Other |

5 |

5.0 |

11 |

6.0 |

|

Total |

99 |

156 |

||

Note: Percentages may not add up to 100 due to rounding off.

Source: Land and Poverty Survey 2010.

Within the non-beneficiary group, 10 households had bought land of their own (some even before the land reform began in 1996), 29 had inherited land (mainly from relatives) in the communal areas, 49 had been allocated land by traditional leaders (chiefs) in the communal areas, and 66 households reported having no plot of land of their own. Table 3 suggests that renting of land was not a common practice among households in this study. Households in the “no land” category had access to common grazing land, especially in communal areas of former homelands, which made it possible for them to keep livestock.

Table 3 Landholdings of non-beneficiary households by type of acquisition and household size, 2010

|

Number |

% |

Household size (mean) |

|

|

Bought |

10 |

6.4 |

4.8 |

|

Inherited |

29 |

18.6 |

8.2 |

|

Allocated by Chiefs |

49 |

31.6 |

6.9 |

|

Renting |

1 |

0.6 |

- |

|

Other |

1 |

0.6 |

- |

|

No land |

66 |

42.0 |

6.3 |

|

Total |

156 |

6.5 |

Note: The category “other” refers to households using a borrowed plot of land.

Source: Land and Poverty Survey 2010.

Data Collection

Data for this study were collected through a single multi-topic household survey questionnaire, administered to both beneficiary (99) and non-beneficiary (156) households.

Calculations of poverty and of the ratio of poor households were based on household expenditure data collected through the consumption section of the questionnaire.

As already noted, apart from the household survey, data were collected through participatory poverty assessments at the project level, involving a number of exercises such as mapping, transect walks, wealth ranking, and timelines.

Study Area

The study was conducted in all the eight local municipalities that make up the Chris Hani District Municipality. Table 4 shows the distribution of the households in the study area.

Table 4 Distribution of beneficiary and non-beneficiary households in Chris Hani District Municipality, by local municipality, 2010

|

Municipality |

Beneficiary |

Non-beneficiary |

Total |

|

Emalahleni |

43 |

54 |

97 |

|

Nkwanca |

6 |

2 |

8 |

|

Intsika Yethu |

3 |

7 |

10 |

|

Inxuba Yethemba |

0 |

1 |

1 |

|

Lukanji |

15 |

24 |

39 |

|

King Sabata Delingebo |

3 |

4 |

7 |

|

Ngcobo |

1 |

1 |

2 |

|

Sakhisizwe |

26 |

53 |

79 |

|

Tsolwana |

2 |

10 |

12 |

|

Total |

99 |

156 |

255 |

Note: King Sabata Delingebo local municipality (KSD) is not part of the Chris Hani District Municipality (CHDM). However, it was included in this study because there are people who received land in CHDM but live in KSD.

Source: Land and Poverty Survey 2010.

The Chris Hani District Municipality (CHDM) covers large parts of the former Ciskei and Transkei homelands.4 Most of the beneficiary and non-beneficiary households chosen for this study come from the communal areas of these two homelands. CHDM is one of six district municipalities in the Eastern Cape province, stretching horizontally across the centre of the province from east to west. The district is largely rural, with a few centres classified as urban settlements.5 These are the administrative centres for the eight local municipalities. The larger part of the district lies in the Karoo, which is a relatively dry area with low rainfall. The district falls within the semi-arid agro-ecological zone, with average annual rainfall of below 600 mm. Because of these climatic conditions, the main agricultural activity in the district is rearing livestock, though rain-fed crops are grown, especially among small-scale farmers who do not have irrigation facilities. Irrigated crops are grown on commercial farms that have irrigation. According to the Community Survey 2007 conducted by Statistics South Africa (2007), CHDM has a total population of 798,449. The 2001 census estimated the population for CHDM at 799,134. The current population of CHDM, according to the information on the official district website, is about 810,000. The majority (89.6 per cent) of the population are Africans, followed by Coloureds (6.9 per cent), Whites (3.1 per cent) and Indians (0.2 per cent).

Findings

Land Holding

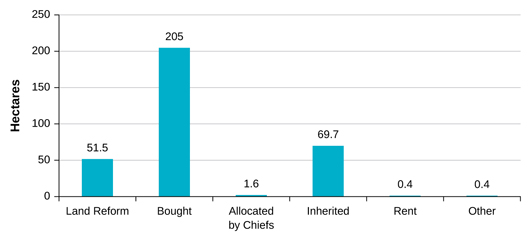

Almost three-quarters of the study households had access to a plot of land (either in the communal area or in newly acquired farms), owned either by the household or by a group to which at least one member of the household belonged. The remaining quarter of households had access to common land for grazing land (which was also open to those who had land of their own). Of the households that had access to land, 52 per cent received land through land reform, while the other 48 per cent received land by other means, including buying land outside of the state’s land reform programme, inheritance, from chiefs and by means of leases (see Table 3). Households that bought land outside the land reform programme had the largest sized plots, followed by land reform beneficiaries, though there are some households in the group with very small plots (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Average size of landholdings of households, by type of acquisition, 2010

Note: For land reform beneficiaries the average land size is smaller because most of the land reform projects are group projects, and so to estimate the average size of land per household, the land owned by a group was divided by the number of members in the group. The number of members in the group used to calculate the average land size for the beneficiaries is that given by the respondents, and is not the number given by the Department of Rural Development and Land Reform.

Source: Land and Poverty Survey 2010.

The key point is that more than 57 per cent of non-beneficiaries have access to land of their own. In terms of type of land ownership, the most diverse group is the land reform beneficiary group (Table 5). This is because the land redistribution programme has been delivered mainly through group projects. As mentioned earlier, land reform beneficiaries had to form groups to meet the “own contribution” requirements in order to get grants from the state (DLA 2001). Related to this is the fact that land reform policy has not encouraged the sub-division of farm land acquired through land reform into small plots that individual beneficiaries could afford to buy and manage on their own (see Lahiff 2008 and Aliber et al. 2011). Survey data on types of landholding are presented in Table 5.

Table 5 Types of landholding, 2010

|

Individual |

Group |

Cooperative |

CPA |

Other |

Total |

|

|

Beneficiary |

24 |

42 |

24 |

9 |

0 |

99 |

|

Bought |

10 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

10 |

|

Inherited |

29 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

29 |

|

Allocated by Chiefs |

48 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

49 |

|

No land |

0 |

1a |

0 |

0 |

1a |

68 |

|

Total |

112 |

43 |

24 |

9 |

1 |

255 |

aThe renting and “other” categories have been included in the “no

land” group, since there is only one household in each category, and also

because those renting and borrowing (“other”) land do not in fact have their

own land.

Notes: (1) CPA=common property

association.

(2) Group=family or non-family

members who belong to different households.

Source: Land and Poverty Survey 2010.

In the non-beneficiary group, most households had access to an individual plot of land, either in communal areas under chiefs, or land bought or inherited outside the communal areas. This was also the position of the beneficiary group before they acquired land through land reform.

Household Incomes and Expenditure

Household income and expenditure are two commonly used measures of well-being. Both assume that income in monetary terms reflects the ability of a household to satisfy its nutritional and other basic requirements (Oosthuizen 2009, Statistics South Africa 2007 and 2008, and Ravallion 1992).

Household income came from various sources, including agricultural production, public transfers (grants), and private remittances, mainly from relatives. Only nine households in the sample reported having a regular salary or wage earner. Net income from agriculture production could not be estimated due to the difficulty in gathering credible information about the various input costs, chiefly costs of labour, feed, seed, and fertilizer (where applicable). Production for own consumption was imputed and forms part of the reported gross income. Total household expenditure figures were estimated from the reported household consumption expenditure data. In this paper, while both household income and expenditure for beneficiaries and non-beneficiaries are reported, household expenditure is used to estimate the poverty ratios for the different groups.

In terms of income and expenditure, it is clear that an average beneficiary household fares much better than a non-beneficiary household, and the difference between the two groups was statistically significant, as suggested by the p-values in Table 6. If we consider income without adding state and private remittances, an average non-beneficiary household has a monthly income which is almost half that of an average beneficiary household. Although this difference cannot entirely be attributed to the influence of land reform, levels of productivity within these households do suggest that having access to land through land reform accounts for a large part of the difference.

Table 6 Monthly household income and expenditure of beneficiary and non-beneficiary households in Rands

|

Beneficiary |

Non-beneficiary |

Gap (per cent) |

p-value |

|

|

Total expenditure |

2548.24 |

2016.29 |

26.4 |

0.0070 |

|

Income (Production value) |

3445.60 |

1733.23 |

99.0 |

0.0000 |

|

Total income + Social grants |

4575.46 |

2938.94 |

56.0 |

0.0000 |

|

Total income + Private remittances |

4663.64 |

3030.60 |

54.0 |

0.0001 |

Notes:

(1) p-value=t-test for group, beneficiary (n=99) and non-beneficiaries

(n=156).

(2) The Rands

(ZAR) reported here are in 2010 prices; the dollar exchange rate that year was about

USD=ZAR7.50

Source: Land and Poverty Survey 2010.

Two major points emerge from Table 7, below. First, the worst group in terms of both income and expenditure were households without land of their own, suggesting that those who have land are better off than the others. In terms of imputed value of agricultural production, it is also clear that households without land had the lowest value, mostly from the sale of livestock and related products. Although the lower average income for households without own land is affected by the fact that they may rely on incomes from non-agricultural sources (which were not captured here), the average monthly household expenditure (which captured all expenditure items) for this group is also the lowest.

Table 7 Monthly agricultural value, income, expenditure and grants of households, 2010 in Rands

|

Agricultural value |

Income |

Expenditure |

Grant |

Grant as % of income |

Grant as % of expenditure |

|

|

Beneficiary |

2710.46 |

3920.59 |

2548.24 |

1130.40 |

41.7 |

60.9 |

|

Bought |

1796.69 |

3032.85 |

2398.99 |

1022.85 |

56.9 |

51.2 |

|

Inherited |

1365.05 |

2969.28 |

2484.85 |

1567.93 |

114.9 |

88.0 |

|

Allocated by Chiefs |

1446.92 |

2918.57 |

1903.63 |

1326.94 |

91.7 |

84.6 |

|

No land |

315.86 |

1383.61 |

1841.37 |

990.88 |

313.7 |

59.6 |

Note: Agriculture value refers to the imputed Rand value from agricultural production. Not all agricultural produce were sold on the market to realise income; most produce were consumed at home.

Source: Land and Poverty Survey 2010.

Secondly, land reform beneficiaries on average had the highest score among the sub-groups on agricultural value, income, and expenditure, suggesting that they produced more than the other groups. It is also interesting to note that the share of social grants in income was lower for beneficiary households and those who bought land outside of land reform than for other sub-groups, suggesting that they were less dependent on social grants as a means of livelihood. These figures do not support the findings of other studies which show that the only major source of income for most land reform beneficiaries are social grants (see Bradstock 2006), although there were beneficiary households who relied largely on social grants.

Since those who had land may have had an advantage with regard to monthly income because our income figures were estimated mainly from reported agricultural production, we also estimated the mean monthly expenditure for the groups. As Table 8 below shows, though the gap in the mean monthly household expenditure fell about 25 per cent when we added social grants, it still remained a substantial difference and was statistically significant at the 5 per cent level. An average beneficiary household spent approximately 26 per cent more than an average non-beneficiary household.

Although the income per capita among land reform beneficiary households was lower than the average income of those who had bought land (due mainly to the larger household size), the average per capita expenditure for land reform beneficiaries was still higher than for all other sub-groups.

Table 8 Monthly per capita income and expenditure of households and household size, 2010 in Rands

|

Income |

Expenditure |

Household size |

[n] |

|

|

Beneficiary |

763.18 |

417.68 |

8.4 |

99 |

|

Bought |

1011.1 |

631.31 |

4.8 |

10 |

|

Inherited |

585.32 |

393.77 |

8.2 |

29 |

|

Allocated by Chiefs |

642.75 |

335.53 |

6.9 |

49 |

|

No land |

426.45 |

353.70 |

6.3 |

68 |

|

Total |

642.51 |

389.03 |

7.4 |

255 |

Source: Land and Poverty Survey 2010.

The monthly per capita income and expenditure of beneficiary households were higher than that of other groups, other than households that had bought land outside of land reform. As is the case with other indicators, the groups with the lowest per capita income and expenditure were households that had no land of their own. However, it is interesting to note that income dispersion among beneficiary households was wider than among non-beneficiaries.

Although the observed difference in income and expenditure between beneficiary and non-beneficiary groups cannot entirely be attributed to the impact of land reform, there is a strong case that land contributes significantly to the livelihoods of landholders in general.

Poverty Head-Count

Differences in economic status among households are also shown by the head-count ratio of poverty, which was higher for non-beneficiary households at all three poverty lines, namely, lower, middle, and upper (Table 9).

Table 9 Poverty head-count ratio and gap between beneficiary and non-beneficiary households, 2010 per cent

|

Without rent |

With rent |

||||

|

Head-count (P0, %) |

Poverty gap (P1, %) |

Head-count (P0, %) |

Poverty gap (P1, %) |

(n) |

|

|

Lower poverty line |

|||||

|

Beneficiary |

67.7 |

54.6 |

57 |

57.6 |

604 |

|

Non-beneficiary |

72.1 |

56.4 |

58 |

58.9 |

853 |

|

Middle poverty line |

|||||

|

Beneficiary |

73.0 |

50.1 |

66 |

55.5 |

604 |

|

Non-beneficiary |

76.8 |

51.4 |

75 |

57.4 |

853 |

|

Upper poverty line |

|||||

|

Beneficiary |

76.3 |

46.9 |

72 |

52.3 |

604 |

|

Non-beneficiary |

83.2 |

48.6 |

75 |

53.3 |

853 |

Note: The upper poverty line (R555.55 per capita) is as used by Statistics South Africa (2008) in the Household Income and Expenditure Survey. The lower poverty line (R416.27) is as proposed by Woolard and Murray (2006). These are at 2006 prices. The middle poverty line is arrived at by calculating the average of the upper and lower poverty lines. There are two sets of calculations: one is without rents because most households did not pay rent and therefore no rent value was captured; the other indicates the imputed value of rent, using the Income and Expenditure Survey’s 2005/2006 proportion for rent, which is 21 per cent of household expenditure for the lower quintile (see Statistics South Africa 2008). Poverty gap ratio (P1) = the average income of those below the poverty line expressed as a percentage of the poverty line.

Source: Land and Poverty Survey 2010.

In both cases (without rent and imputed rent) the poverty head-count (P0) for beneficiary households was lower than for non-beneficiary households. However, the poverty gap was higher for beneficiary households at the middle and upper poverty lines, suggesting that average incomes at the lower end of the beneficiary group were very small. This is confirmed by the large standard deviation reported for the beneficiary groups. When the poverty lines were adjusted for inflation to reflect 2010 prices, the lower poverty line head-count ratio for beneficiaries increased to 74.3 per cent and for non-beneficiaries to 79.4 per cent. For the upper poverty line head-count ratio there was little difference between the two groups (beneficiaries = 88.7 per cent, non-beneficiaries = 89.7 per cent), suggesting that, in both groups, very few households had incomes above the upper poverty line.

When the poverty head-count ratio was disaggregated across non-beneficiary sub-groups, it was apparent that, on average, the poverty ratios were lower among those who bought land outside of land reform than among any other group, including land reform beneficiaries (Table 10). However, the poverty ratios for land reform beneficiaries were lower than for the other groups at all three poverty lines. These differences may also reflect the differences in dependency ratios between the groups (see Table 7 above).

Table 10 Poverty head-count ratio of households, 2010 per cent

|

Lower poverty line |

Middle poverty line |

Upper poverty line |

|

|

Beneficiary |

67.7 |

73.0 |

76.3 |

|

Bought |

23.7 |

31.6 |

47.4 |

|

Inherited |

77.0 |

77.0 |

84.7 |

|

Allocated by Chiefs |

74.1 |

83.5 |

86.0 |

|

No land |

73.7 |

77.1 |

84.5 |

Source: Land and Poverty Survey 2010.

When the beneficiaries group was disaggregated by type of land ownership, households with individual plots were seen to have higher incomes and expenditures (Table 11). Other indicators such as livestock ownership, crop production, and growth in agriculture production since land was transferred also showed that beneficiary households with individual plots performed better than others. One of the main reasons given for the better performance of individual family farms vis-à-vis group projects was that there were conflicts in group projects that sometimes affected production activities (Hall and Cliffe 2009).

Table 11 Monthly income and expenditure of beneficiary households, 2010

|

Individual plot |

Group plot |

|

|

Income |

4991.16 |

3472.46 |

|

Expenditure |

3245.47 |

2236.32 |

|

Per capita income |

941.73 |

560.07 |

|

Per capita expenditure |

604.74 |

362.10 |

Source: Land and Poverty Survey 2010.

Agricultural Production

In terms of the production activities of households that owned land, we first looked at livestock and crop production within beneficiary and non-beneficiary households, and then disaggregated the groups.

With regard to livestock, land reform beneficiaries had more cattle and sheep on average than other groups (Table 12). Households without landholdings had the lowest numbers of livestock in every category. This is most probably because the latter did not have access to additional land for grazing and relied exclusively on communal grazing land. Given that livestock has become a major source of income as a result of the demand generated by a range of anniversaries, funerals and ceremonies in the study area, it was not surprising that the land reform beneficiaries had higher incomes on average than other groups.

Table 12 Livestock ownership of households, 2010 in numbers

|

Cattle |

Sheep |

Goats |

Pigs |

|

|

No land |

4.5 |

11.0 |

3.0 |

0.45 |

|

Beneficiary |

29.9 |

71.4 |

11.4 |

0.48 |

|

Bought |

14.7 |

32.7 |

13.7 |

0.60 |

|

Inherited |

13.8 |

30.9 |

8.2 |

0.17 |

|

Allocated by Chiefs |

8.4 |

23.3 |

4.4 |

0.97 |

Source: Land and Poverty Survey 2010.

Households with ownership holdings of land had more livestock on average, though the extent of the holding did not correlate with the number of livestock (see Figure 1 above). As Table 13 shows, figures for growth in livestock numbers over the past 10 years suggest that households with holdings of land recorded the highest growth in livestock numbers, with land reform beneficiary households recording the highest numbers with respect to cattle, sheep, and goats, while those without land recorded the lowest growth in all livestock categories.

Table 13 Mean growth in livestock ownership of households, 2001–10 in numbers

|

Cattle |

Sheep |

Goats |

Pigs |

|

|

Beneficiary |

16.6 |

51.4 |

4.7 |

0.2 |

|

Non-beneficiary |

3.0 |

10.9 |

1.8 |

0.3 |

|

Bought |

10.2 |

13.9 |

9.0 |

0.6 |

|

Inherited |

4.2 |

7.8 |

6.2 |

0.13 |

|

Allocated by Chiefs |

2.4 |

15.2 |

–1.8 |

0.7 |

|

No land |

2.0 |

9.2 |

2.2 |

0.3 |

Note: The mean growth figures exclude livestock jointly owned.

Source: Land and Poverty Survey 2010.

Livestock ownership and sale constituted an important livelihood source for rural households in the study area, mainly because the area is semi-arid, which is not ideal for crop production. Livestock production may explain the higher incomes among land reform beneficiaries reported in this study as compared to those reported in studies conducted in provinces such as Limpopo and Mpumalanga, where crop production was the main source of livelihood and livestock holdings were low. For example, a study of land reform projects in Limpopo reported that the average annual household income from agricultural production was R307 (Anseeuw and Mathebula 2008, p. 34), which is less than 10 per cent of the estimated average monthly income for land reform beneficiary households in our study (Table 7 above).

Higher growth in livestock on average among beneficiary households can be attributed to the fact that land reform beneficiaries moved their livestock from the communal grazing land where the livestock was vulnerable to disease, theft, impoundment, and poor grazing due to overstocking. Most of the respondents confirmed this during the participatory poverty analysis (see Table 14).

Table 14 Land reform programme livestock profile

|

Farm |

Vukuzenzele |

Chewu |

Funokuhle |

Siyafuya |

Amaxisibe |

Delindlala |

Mukoena |

Magobotiti |

Koffifontein |

|||||||||

|

Year |

2004 |

2010 |

2004 |

2010 |

2004 |

2010 |

2004 |

2010 |

2004 |

2010 |

2004 |

2010 |

2004 |

2010 |

2004 |

2010 |

2004 |

2010 |

|

Livestock |

||||||||||||||||||

|

Cattle |

37 (10) |

28 (9) |

78 |

76 |

42 |

49 |

78 |

86 |

8 |

39 |

-- |

339 (278) |

27 |

27 |

|

|

-- (19) |

93 (23) |

|

Goats |

(3) |

(10) |

0 |

25 |

0 |

0 |

54 |

86 |

5 |

57 |

0 |

0 |

8 |

8 |

|

|

(63) |

(40) |

|

Sheep |

0 |

0 |

311 |

147 |

190 |

400 |

90 |

147 |

12 |

85 |

-- |

906 |

14 |

14 |

|

|

(0) |

(8) |

|

Size (Ha) |

|

172 |

|

326 |

|

527 |

|

731 |

|

8 |

|

2029 |

|

745 |

|

453 |

|

731 |

|

Number of People |

|

5 |

|

5 |

|

Family |

|

4 |

|

Family |

|

36 |

|

14 |

|

5 |

|

27 |

|

Notes |

No crop production, animals died of diseases, a few sold over the years |

Limited crop production. Some animals were sold, others stolen |

A variety of crops produced, mainly maize. Livestock sold over the years. |

No crop production. Individual livestock sold over the years. |

Various crops produced. Livestock sold over the years |

Group crops are grown. Individual livestock sales over the years |

Recently acquired farm |

Recently acquired farm |

Limited individual crop production. No livestock sales except chicken |

|||||||||

Notes: The figures in brackets indicate the number of livestock that belong to individual members out of the total for the group. The “start” and “now years refer to the year when the farm was transferred and the time when the time line was drawn . Because there are no records on what is produced or sold on the farms, the figures recorded here are entirely based on the recollection of the PPA participants for each project. In most of the projects, participants indicated that they sold livestock to buy farm equipment, inputs or for other household goods. The exact number of sales could not be established. For groups that are producing crops, the survey data estimated the annual production.

Source: Data from participatory poverty assessment (PPA)

A higher proportion of beneficiary households is involved in crop production than other groups (Table 15).

Table 15 Crop and vegetable production by households, 2010

|

Household crop production (per cent) |

Average units |

|||

|

Beneficiaries |

Non-beneficiaries |

Beneficiaries |

Non-beneficiaries |

|

|

Maize |

55.5 |

36.5 |

20.0 (50 kg) |

4.2 (50 kg) |

|

Potato |

42.4 |

33.9 |

10.0 (10 kg) |

17.9 (10 kg) |

|

Cabbage |

40.4 |

25.0 |

||

|

Spinach |

39.9 |

22.5 |

||

|

Beans |

32.3 |

22.4 |

||

|

Vegetables |

26.2 |

12.8 |

||

|

Onion |

33.3 |

27.5 |

6.8 (10 kg) |

8.9 (10 kg) |

|

Fodder |

32.3 |

6.4 |

5.8 (bale) |

0.5 (bale) |

|

Tomato |

17.1 |

14.23 |

||

|

Squash |

4.0 |

2.5 |

||

|

Citrus |

4.0 |

0.6 |

||

|

Peas |

3.0 |

6.4 |

||

|

Sorghum |

3.0 |

0.0 |

||

|

Lettuce |

2.0 |

5.1 |

||

Note: [10 Kg]=10 kilogram sac or pocket; [50 Kg]=50 kilogram sac. These sacs may not exactly weigh 10 Kg or 50 Kg, but that is the unit used to measure the particular produce.

Source: Land and Poverty Survey 2010.

In the case of maize, a beneficiary household produced almost five times more on average than a non-beneficiary household. However, non-beneficiary households produced more potato and onion than beneficiaries. This has been attributed to the fact that potatoes and onions are labour-intensive crops requiring individual focus, which the beneficiary households were not able to provide because most of them stayed far away from their farms.

Post-Transfer Support

The proportion of households that reported receiving agricultural support from the state was surprisingly small, particularly since land reform beneficiaries were expected to receive state support to enable them to fully utilise the acquired land. Only 16 per cent of beneficiary households received livestock support after land was transferred (Table 16). None of these households was given special training in farming skills or agricultural management.

Table 16 Agricultural assistance received from the state by beneficiary and non-beneficiary households, 2001–10 per cent

|

Beneficiaries |

Non-beneficiaries |

|

|

Livestock |

16.1 |

1.9 |

|

Farm equipment |

4 |

1.9 |

|

Seeds |

9 |

3.2 |

|

Fertilizer |

1 |

0.6 |

|

Farming skills |

0 |

0.6 |

|

Fencing |

2 |

0.0 |

|

Irrigation infrastructure |

1 |

0.0 |

|

Credit |

1 |

0.0 |

|

Soil testing |

1 |

0.6 |

|

Other |

0 |

1.2 |

|

Agriculture management |

0 |

0.0 |

|

Dipping infrastructure |

2 |

0.0 |

|

None |

61.6 |

89.7 |

Source: Land and Poverty Survey 2010.

A similar picture emerged with respect to access to credit (Table 17). Only four land reform beneficiary households reported having received an agriculture loan in the past 10 years. Interestingly, about three-quarters of the beneficiary households indicated that they would like to secure an agriculture loan in the future, if the opportunity arose. Lack of access to credit constrains the production potential of these households.

Table 17 Access to credit for beneficiary and non-beneficiary households, 2001–10

|

Beneficiaries |

Non-beneficiaries |

|

|

General loan |

9 |

2 |

|

Agricultural loan |

4 |

2 |

|

Plans for future loan |

74 |

35 |

|

Loan provider |

||

|

Land bank |

2 |

0.6 |

|

Dept of Agriculture |

0 |

0.6 |

|

Cooperative |

1 |

0.0 |

|

Other |

1 |

0.6 |

|

No loan |

96 |

98 |

Source: Land and Poverty Survey 2010.

Sustained and coordinated state support can help these households produce much more than they are producing at the moment. The production levels reported above were accomplished despite inadequate or, in most cases, no support.6

Our survey data also suggest that land reform beneficiaries had a more positive assessment of life in general. When asked how they would rate their lives over the past 10 years, more land reform beneficiaries (66 per cent) reported positive improvements in their lives than non-beneficiaries (43 per cent) (Table 18).

Table 18 General assessment of life over the past 10 years by beneficiary and non-beneficiary households, 2001–10

|

Beneficiaries |

Non-beneficiaries (per cent) |

|

|

Greatly improved |

26.0 |

13.4 |

|

Slightly improved |

40.2 |

29.6 |

|

No improvement |

11.3 |

32.4 |

|

Worsened |

6.2 |

6.4 |

|

Slightly worsened |

4.1 |

5.6 |

|

Greatly worsened |

10.3 |

12.6 |

Source: Land and Poverty Survey 2010.

Table 18 summarises the data from the participatory poverty assessments. Most land reform beneficiaries said that their lives had improved since they received land, while the non-beneficiary groups indicated that lack of access to land made it difficult for them to improve their lives.

Concluding Remarks

This paper, based on a study conducted in the Chris Hani District Municipality (CHDM), Eastern Cape, establishes three main points. First, having access to land has made a difference to the lives of rural households in general. Although there was unevenness across the land reform programmes, the data show that the living conditions of beneficiaries of land reform were better than that of those without land. Secondly, households of beneficiaries of land reform and those who acquired land on their own were far better off (in all aspects) than those who owned little or no agricultural land. The difference between these groups of households stands out most apparently in respect of livestock production. This is not surprising, given the overcrowded conditions in the rural areas of the former Bantustans where grazing land is periodically converted into residential land whenever there is a need for housing. As we indicate in the paper, the issue of livestock production is perhaps crucial in explaining the glaring differences between the conclusions of our study and the conclusions of studies discussed in section 2, most of which were conducted in Limpopo province where crop production is central.

On the matter of support from the state, we agree with the conclusion of most analysts that little or no support was provided to the beneficiaries of land reform. However, unlike other analysts, we argue that those who had access to land were able to improve their livelihoods despite this lack of support. We further argue that with more coordinated and sustained post-land transfer support, the beneficiaries can use their land better and thus make better gains in the struggle against poverty.

Finally, we argue that many of the poor households in rural areas pursue livelihoods that are neither entirely dependent on subsistence agriculture (crop or livestock) nor entirely divorced from farming. Most rural households use land as a base from which to launch other livelihood strategies (Chimhowu 2006), including vending, small-scale retail, brick-making and selling wood fuel. As such, access to land remains the main safety net when other strategies fail.

Acknowledgements: We are grateful to Professor Murray Lebbrandt (School of Economics, University of Cape Town) for his advice on imputing income from agricultural production, and also for assisting with the data analysis. We are also grateful to two anonymous reviewers for useful comments and suggestions.

Notes

1 The study does not include restitution projects of land reform. This is mainly because there are very few land claim cases in the area where the study is located, but also because most of the settled claims are in urban areas where the beneficiaries have opted for cash payments and not land (see DLA 2009, pp. 49-50).

2 The official unemployment rate for the third quarter of 2011, was estimated at 25 per cent. But this figure under reports the actual unemployment by excluding the discouraged job seekers, who are effectively characterised as being out of the labour market (see Chitonge 2010). If the discouraged job seekers are included, the real unemployment figure for the third quarter of 2011 is 37.9 per cent (this calculation is based on data from Statistics South Africa 2011, p. 6).

3 One of the reasons why beneficiaries do not leave their areas is that most of the farms are far away from social services including schools, clinics, water services, and markets. Thus most land reform beneficiaries go to work on the farm, leaving the rest of the family in the communal areas.

4 In one project, out of an initial number of 49 members only 3 members belonging to 2 households were involved in the land reform project (see Aliber et al. 2011, p. 69).

5 There are several reasons why most of the land reform beneficiaries have not moved to the newly acquired land, but the two most important ones are that, first, in most cases, farms are acquired as a group and subdivision of the farms is not allowed, and, secondly, most farms are far away from social services, including schools, clinics, water services, and markets. Thus, most land reform beneficiaries go to work on the farm and come back to stay in the communal areas.

6 There are now many examples of how coordinated government support to subsistence farmers has not only increased food production, but has also improved the food security of the subsistence households as the nation at large. The fertiliser subsidy programme in Malawi and the Farmer Input Support programme in Zambia are just two current examples.

References

| ANC (African National Congress) (1994), The Reconstruction and Development Programme: A Policy Framework, Umanyano Publications, Johannesburg. | |

| Aliber, M., Maluleke, T., Manenzhe, T., Paradza, G., and Cousins, B. (2011), “Livelihoods after Land Reform: Trajectories of Change in Limpopo Province, South Africa,” Institute for Poverty, Land and Agrarian Studies (PLAAS), University of the Western Cape, Bellville. | |

| Anseeuw, W., and Mathebula, N. (2008), “Evaluating Land Reform’s Contribution to South Africa’s Pro-Poor Growth Pattern,”paper presented at the TIPS Annual Forum. | |

| Beinstein, A. (2005), “Rethinking Reform: Twelve Steps to Land Reform,” Business Daily, June 14, 2005. | |

| Bigsten, A., Kebede, B., Shimeles, A., and Taddesse, M. (2003), “Growth and Poverty Reduction in Ethiopia: Evidence from Household Panel Surveys,” World Development, vol. 31, no. 1, pp. 87–106. | |

| Bradstock, Alastair (2006), “Land Reform and Livelihoods in South Africa’s Northern Cape Province,” Land Use Policy, 23, pp. 247–59. | |

| Bryceson, D. F. (1999), “Sub-Saharan Africa Betwixt and between: Rural Livelihood Practices and Policies,” De-Agrarianisation and Rural Employment (DARE), Afrika –Studiecentrum (ASC) Working Paper No. 43, available at www.asc.leidenuniv.nl/general/dare.htm, viewed on May 13, 2009. | |

| Bryceson, D. F. (2002), “The Scramble in Africa: Reorienting Rural Livelihoods,” World Development, vol. 30, no. 5, pp. 725–39. | |

| Carter, Michael, and May, Julian (1997), “Poverty, Livelihood and Class in Rural South Africa,” Agricultural and Economics Staff Paper Series, no. 408, University of Wisconsin. | |

| Community Agency for Social Enquiry (CASE) (2006), Assessment of the Status-quo of Settled Land Restitution Claims with a Developmental Component Nationally, study conducted by CASE for the Monitoring and Evaluation Directorate of the Department of Land Affairs (DLA). | |

| Centre for Development and Enterprise (CDE) (2005), Land Reform in South Africa: A 21st Century Perspective, research report no. 14. | |

| Centre for Development and Enterprise (CDE) (2008), “Land Reform in South Africa: Getting Back on Tract,” research report no. 16, available at www.cde.org.za/article.php?a_id=284, viewed on June 17, 2010. | |

| Chimhowu, Admos (2006), “Tinkering on the Fringes? Redistributive Land Reforms and Chronic Poverty in Southern Africa,” Chronic Poverty Research Centre Working Paper No. 58. | |

| Chitonge, Horman (2010), “The State of KwaZulu-Natal Labour Market,” in N. Nzimande (ed.), State of the Population of KwaZulu-Natal: Demographic Profile and Development Indicators, KZN Provincial Department of Social Development, Pietermaritzburg. | |

| Deininger, Klaus (2003), Land Policies for Growth and Poverty Reduction, Oxford University Press, New York. | |

| Deininger, Klaus, and May, Julian (2000), “Can There be Growth with Equity? An Initial Assessment of Land Reform in South Africa,” World Bank Policy Research Working Paper No. 2451, available at www.worldbank.org, viewed on February 19, 2009. | |

| DRDLR (Department of Rural Development and Land Reform) (2010), Annual Report 2008/2009, DRDLR, Pretoria, available at www.info.gov.za/view/downloadFileAction=125561, viewed on October 12, 2011. | |

| DRDLR (Department of Rural Development and Land Reform) (2011), Annual Report 2009/2010, DRDLR, Pretoria, available at www.info.gov.za/view/downloadFileAction=125561, viewed on October 12, 2011. | |

| DLA (Department of Land Affairs) (1997), White Paper on South African Land Policy, Government Printers, Pretoria. | |

| DLA (Department of Land Affairs) (2001), Land Redistribution for Agricultural Development, Government Printers, Pretoria. | |

| DLA (Department of Land Affairs) (2009), Annual Report 2007/2008, DRDLR, Pretoria, available at www.info.gov.za/view/downloadFileAction=125561, viewed on October 12, 2011. | |

| Eastwood, Robert, Kirsten, Johann, and Lipton, Michael (2006), “Can Land Redistribution Help Reduce Rural Dependency in South Africa?” Journal of Development Studies, vol. 42, no. 8, pp. 1325–49. | |

| Expert Group on Poverty Statistics (EGPS, Rio Group) (2006), “Compendium of Best Practice in Poverty Measurement,” Economic Development and Cultural Change, vol. 49, no. 1, Rio de Janeiro, pp. 197–211. | |

| Finan, Frederico, Sadoulet, Elisabeth, and de Janvry, Alain (2005), “Measuring the Poverty Reduction Potential of Land in Rural Mexico,” Journal of Development Economics, vol. 77, pp. 27–51. | |

| Hall, R. (2009), “Land reform for what? Land use, production and livelihoods,” in R. Hall and L. Cliffe (eds.), Another Countryside? Policy Options for Land and Agrarian Reform in South Africa, Institute for Poverty, Land and Agrarian Studies, Bellville, pp. 23–62. | |

| Hall, R., and Cliffe, L. (2009), “Introduction,” in R. Hall and L. Cliffe (eds.), Another Countryside? Policy Options for Land and Agrarian Reform in South Africa, Institute for Poverty, Land and Agrarian Studies, Bellville, pp. 1–22. | |

| Hall, R., and Ntsebeza, L. (2007) “Introduction,” in L. Ntsebeza and R. Hall (eds.), The Land Question in South Africa: the Challenge of Transformation and Redistribution, HSRC Press, Cape Town. | |

| Hazel, Peter (2005), “The Role of Agriculture and Small Farms in Economic Development,” Proceedings of a workshop on “Future of Small Farms” held in Wye, Kent, 26–29 June 2005. | |

| Hendricks, Fred, and Ntsebeza, Lungisile (2010), “Black Poverty and White Property in Rural SA,” in Brij Maharaj, Ashwin Desai, and Patrick Bond (eds.), Zuma’s Own Goal: Losing South Africa’s ‘War on Poverty’, Africa World Press, Trenton. | |

| Hofstatter, Stephan (2009), "Minister Warns Land Reform Beneficiaries," Businessday, March 5, available at http://allafrica.com/stories/printable/200903050078.html, viewed on November 14, 2010. | |

| Human Science Research Council (HSRC) (2003), Land Redistribution for Agricultural Development (LRAD): Case Studies in Three Provinces, HSRC, Pretoria. | |

| Johnston, Bruce, and Mellor, John (1961), “The Role of Agriculture in Economic Development,” The American Economic Review, vol. 51, no. 4, pp. 556–93. | |

| Johnston, D. Gale (1993), “The Role of Agriculture in Economic Development Revisited,” Agricultural Economics, vol. 8, pp. 421–34. | |

| Keswell, M., Carter, M., and Deininger, K. (2009), “Poverty and Land Ownership in South Africa,” draft, available at www.saldru.uct.ac.za, viewed on February 20, 2011. | |

| Lahiff, E. (2007), “Land Redistribution in South Africa: Progress to Date,” paper prepared for the workshop “Land Redistribution in Africa: Towards a common vision,” Regional Course, Southern Africa, July 9–13, 2007. | |

| Lahiff, E. (2008), “Redistribution, Land Reform and Poverty Reduction in South Africa,” a Working Paper for the research on “Livelihoods after Land Reform.” | |

| Lewis, Arthur (1954), “Economic Development with Unlimited Supplies of Labour,” Manchester School, vol. 22, pp. 139–91. | |

| Liebenberg, F., and Pardey, P. G. (2010), “South Africa Agricultural Production and Productivity Patterns,” in The Shifting Patterns of Agricultural Production and Productivity Worldwide, Ames, Iowa. | |

| Lipton, Michael, Ellis, Frank, and Lipton, Merle (1996), “Introduction,” in M. Lipton, M. de Klerk, and M. Lipton (eds.), Land Labour and Rural Livelihoods in South Africa (Vol. 1), University of Natal Press, Durban, pp. v–xxii. | |

| López, R., and Valdés, A. (2000), “Fighting Rural Poverty in Latin America: New Evidence of the Effects of Education, Demographics and Access to Land,” Economic Development and Cultural Change, vol. 49, no. 1, pp. 197–211. | |

| Lyne, Mike, and Darroch, Mag (2003), “Land Redistribution in South Africa: Past Performance and Future Policy,” BASIS CRSP research paper, available at www.basis.wisc.edu, viewed on November 22, 2008. | |

| Makhanya, Mondli (2009), “This isn’t Zimbabwe, So Let Us Ditch the Myth of Land-hungry Masses,” Timeslive, October 17, 2009, available www.timeslive.co.za/opinion/columnist, viewed on September 23, 2010. | |

| May, Julian, and Roberts, Benjamin (2000), “Monitoring and Evaluating the Quality of Life of Land Reform Beneficiaries: 1998/1999,” Summary Report prepared for the Department of Land Affairs (DLA). | |

| May, Julian, Steven, Thild, and Stols, Annareth (2002), “Monitoring the Impact of Land Reform on Quality of Life: A South African Case Study,” Social Indicators research, vol. 58, pp. 293–312. | |

| Moyo, Sam, Walter, Chambati, Murisa, Tendai, Siziba, Dumisani, Dangwa, Charity, Mujeyi, Kingston, and Nyoni, Ndabezinhle (2009), Fast Track Land Reform Baseline Survey in Zimbabwe: Trends and Tendencies 2005/06, African Institute for Agrarian Studies, Harare. | |

| National

Planning Commission (NPC) (2011), National Development Plan: Vision 2030,

available at http://www.npconline.co.za/medialib/downloads/home/NPC%20National%20 Development%20Plan%20Vision%202030%20-lo-res.pdf, viewed on November 22, 2011. | |

| Nkwinti, G. (2010a), “Use Land or Lose it—Nkwinti,” News, March 24, 2010. | |

| Nkwinti, G (2010b), “Speech by the Minister of Rural Development and Land Reform: Budget Vote for 2010/11,” March 24, 2010, http://www.ruraldevelopment.gov.za, viewed on August 19, 2010. | |

| Ntsebeza, L., and Hall, R., (eds.) (2007) The Land Question in South Africa: the challenge of transformation and redistribution, HSRC Press, Cape Town. | |

| Ntsebeza, L., and Hendricks, F. (2000), “The Paradox of South Africa’s Land Reform Policy,” SARIPS Annual Colloquium, Harare, Zimbabwe. | |

| Oosthuizen, Morne (2009), “Estimating Poverty Lines for South Africa,” Development Policy Research Unit Discussion Paper, University of Cape Town. | |

| Phaahla, J. (2010), “Speech by the Deputy Minister of Rural Development and Land Reform,” Budget Vote for 2010/11, March 24, 2010, http://www.ruraldevelopment.gov.za, viewed on May 19, 2010. | |

| Ranis, Gustav, and Fei, John (1961), “A Theory of Economic Development,” American Economic Review, vol. 51, no. 4, pp. 533–65. | |

| Ravallion, Martin (1992), “Poverty Comparisons: A Guide to Concepts and Methods,” Living Standards Monitoring Survey (LSMS) Working Paper No. 133, World Bank, available at http://www.worldbank.org/LSMS/research/wp/wptitle.html, viewed on July 12, 2005. | |

| Ravallion, Martin (2001), “The Mystery of the Vanishing Benefits: An Introduction to Impact Assessment,” World Bank Economic Review, vol. 15, no.1, pp. 115–40. | |

| Ravallion, Martin (2008), “Evaluating Anti-Poverty Programmes,” in T. P. Schultz and J. Strauss (eds.), Handbook of Development Economics, volume 4, Elsevier, Amsterdam, pp. 3788–846. | |

| Republic of South Africa (1970), Subdivision of Agricultural Land Act 70 of 1970, available at http://www.plato.org.za/pdf/legislation/Subdivision%20of%20Agricultural%20Land%20-%20Act%2070%20of%201970.pdf, viewed on September 21, 2011. | |

| Rigg, Jonathan (2006), “Land, Farming, Livelihoods, and Poverty: Rethinking the Links in the Rural South,” World Development, vol. 34, no. 1, pp. 180–202. | |

| Schultz, Theodore (1964), Transforming Traditional Agriculture, Yale University Press, New Haven. | |

| Statistics South Africa (2007), “A National Poverty Line for South Africa,” available at www.treasury.gov.za, viewed on June 18, 2011. | |

| Statistics South Africa (2008), Incomes and Expenditure of Household 2005/0, Statistical Release P0100, available at www.statssa.gov.za, viewed on May 29, 2011. | |

| Statistics South Africa (2011), Quarterly Labour Force Survey: Quarter 3, 2011, Statistical Release P0211, available at http://www.statssa.gov.za/publications/P0211/P02113rdQuarter2011.pdf, viewed on November 29, 2011. | |

| Valdes, Alberto, and Foster, William (2005), “Reflections on the Role of Agriculture in Pro-poor Growth,” Proceedings of a Workshop on “Future of Small Farms,” held in Wye, Kent, June 26–29, 2005. | |

| van den Brink, Rogier, Thomas, Glen, Bruce, John, and Byamugisha, Frank (2006), “Consensus, Confusion and Controversy: Selected Land Reform in Sub-Saharan Africa,” World Bank, Washington DC, available at www.worldbank.org, viewed on February 13, 2009. | |

| Vink, Nick, and van Rooyen, Johan (2009), “The Economic Performance of Agriculture in South Africa since 1994: Implications for Food Security,” working paper series no. 17, Development Planning Division, Development Bank Southern Africa. | |

| Woolard, Ingrid, and Leibbrandt, Murray, (2006), “Towards a Poverty Line for South Africa: A Background Note, available at http://www.treasury.gov.za, viewed on September 18, 2010. | |

| World Bank (2006), World Development Report 20006: Equity and Development, The World Bank, Washington D. C. |