CURRENT ISSUE

Vol. , No.

JULY-DECEMBER, 0000

Restructuring the Economy of Women’s Work

on the Assam-Dooars Tea Plantations

*Professor of Economics, Sikkim University, jeta_eco@rediffmail.com

Abstract: Colonial annexations in Northeast India opened the way for planter capital. Plantations needed a large permanent labour force for planting the new territories. In order to meet this demand, systems of indentured labour brought Adivasi families from central India to Assam and the Dooars.

Even after the end of indentured labour, the tea labour system tied entire families for several generations to plantation work. Recent reorganisations of the tea industry through fair trade initiatives for smaller plantations, which only produce and sell green leaf, are viewed as a desirable erosion of the tied labour system. Yet given the piece-rated form of payment for women’s plantation work, do these changes offer a fair solution for women pluckers, who constitute half of the tea labour force? This question is explored in the context of the complex labour history of plantations and recent organisational changes within the Assam-Dooars tea industry.

Keywords: tea, plantation, women workers, pluckers, piece-rate, Assam, Dooars, Northeast India, tea production, exports.

India in the Global Tea Enterprise

Tea entered the global economy during the period of mercantile rivalry between the Dutch Verenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie (VOC, chartered 1602) and the British East India Company (EIC, chartered 1600). Nevertheless, for more than 200 years, the sources of tea were confined to the traditional growing countries of China and Japan. In 1833, when the renewal of the EIC Charter ended the EIC monopoly on tea trade across Britain and the colonies, a Tea Committee appointed in 1834 recommended experimentation with planting tea in the newly-annexed territories of Assam and the Himalayas. When the experiment proved successful, the first shipment of 47 chests of Assam tea was auctioned for a promising price at the London Auction in 1839. Exports of Chinese black tea were outcompeted by Indian black tea in terms of average costs and quality within a period of 30 years. From that success onwards, as tea became an item of mass consumption in complementarity with cheap sugar, a strong role was established for Indian tea plantations in the global tea enterprise.

Table 1 Recent trends in global tea production and tea exports, 2012–2016 in million kg

| World tea production | World tea exports | ||||||||||

| Country | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 (P) | Country | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 (P) |

| China | 1,789.8 | 1,924.5 | 2,095.7 | 2,249 | 2,350 | China | 321.8 | 332.4 | 301.5 | 325 | 328.7 |

| India | 1,126.3 | 1,200.4 | 1,207.3 | 1,208.7 | 1,239.2 | India | 208.3 | 219.1 | 207.4 | 228.7 | 216.8 |

| Kenya | 369.6 | 432.5 | 445.1 | 399.2 | 474.8 | Kenya | 430.2 | 494.4 | 499.4 | 443.5 | 480.3 |

| Sri Lanka | 328.4 | 340 | 338 | 329 | 292.4 | Sri Lanka | 306 | 309.2 | 317.9 | 301.3 | 280.9 |

| Vietnam | 174 | 180.3 | 175 | 170 | 165 | Vietnam | 144 | 140.3 | 132 | 133.5 | 127 |

| Indonesia | 137.8 | 136.9 | 135.7 | 129.3 | 125.5 | Indonesia | 70.1 | 70.8 | 66.4 | 61.9 | 50 |

| Others | 769.5 | 781.3 | 802.7 | 796.4 | 815.9 | Others | 295.1 | 294.6 | 301.7 | 305.6 | 293.9 |

| Total | 4,695.3 | 4,995.8 | 5,199.6 | 5,281.5 | 5,462.7 | Total | 1,775.5 | 1,860.8 | 1,826.3 | 1,799.4 | 1,777.6 |

Note: P stands for provisional.

Source: Adapted from International Tea Committee (ITC) data.

Although China remained the largest global producer of tea on the strength of its large domestic tea market, the British colonies of India, Sri Lanka, and later Kenya became the dominant exporters of tea to British tea blenders, enabling the British beverage industry to rule global markets. Today, the situation has changed appreciably. Together, nearly 80 per cent of global tea exports are sourced from the four countries just mentioned, with Indian tea exports in 2014 being valued at USD 746 million (IBEF 2016). With China resurgent in global tea exports, a considerable squeeze has been applied on Indian tea exports despite major expansion in Indian tea production over the last 50 years. In the absence of increasing tea exports, the mass of Indian tea is now domestically consumed. By contrast, India’s major competitors in tea exports, Sri Lanka and Kenya, export nearly all the tea they produce. Kenyan and Sri Lankan tea are therefore more sensitive to global tea preferences, while Indian tea in large part caters to a less discerning domestic market. In terms of overall proportion, quality tea produced in India is a smaller share of the total than in Sri Lanka and Kenya.

Recent figures also show that Kenya exports more tea than it produces. This points to Kenya’s gradual emergence as the global centre for tea trade after the closure of the 300-year Mincing Lane Tea Auctions in London in 1998 (Talbot 2002). With the major international tea blenders all active in the Kenyan auctions, third-party teas are now increasingly dealt with at these auctions, pushing the tea auctions at Kolkata, Colombo, and elsewhere into subsidiary trading positions.

India now consumes domestically more than four-fifths of its annual tea crop, making the demand for tea highly sensitive to domestic tea prices. While tea exports remain a large foreign exchange earner for India, the rise of tea competition from other countries and the sluggishness of tea earnings as a result of a long-term decline in global tea prices have played increasing havoc with the Indian tea plantation industry over at least 20 years, disrupting production patterns and production relations. Tea workers, still the most powerless of all organised sector workers, must bear the brunt of commercial adjustments.

As women have traditionally constituted more than half the tea workforce, working in plucking operations as field-workers, the brunt of labour adjustments has been borne by income-poor plantation women, who have seen erosion in their status, social power, and earnings. The largest segment of the Indian tea labour force is deployed in the tea-growing regions of Assam and West Bengal, and the two States have seen dismal conditions in the tea sector. There has been worker distress, and starvation deaths over two decades, without adequate measures for restitution of worker rights.

The contexts prevailing in the Assam and West Bengal tea industry, their manifestations and proximate causes and reasons are outlined in reference to global and Indian tea trends in this study.

The Advent of Tea in Eastern and Northeastern India

Colonial annexations of territory in Northeast India, of Assam from Burma (1826), the Darjeeling hills from Sikkim (1835), and Bengal and the Assam Dooars from Bhutan (1865) opened the way for planter capital. Plantations needed a large permanent labour force to plant new territories. Just as Indian indenture system transported Indian coolie labour to colonial sugar colonies in the Caribbean and the Indian Ocean, internal indenture brought Adivasi families from central India to Assam. In a later phase, labouring families from the Nepal hills were brought to the Darjeeling hills after being recruited by labour sardars, while Adivasi labour for the Bengal and Assam Dooars was recruited from Jharkhand and Chhattisgarh through free labour agents or arkatis, Lutheran and Catholic missions, and Tea District Labour Boards.

The scale of labour migration into new tea territories during this period was immense. At the same time, it also encouraged voluntary migration and methods to resolve the inequities of enslaved plantation labour markets in the past era. The tea labour system tied entire families for several generations into a reproducible workforce for plantation work.

Reorganisation of plantations in India over a century and a half has been gradual and obscure. Changes have nevertheless occurred in the dominant modes of ownership and control of plantations, in the national and international markets supplied by plantation products and their marketing chains, and in the dominant scale of operation of plantations.

Women have always played a pivotal role as field workers in plantation production. Gradual changes in the plantation industry in Assam and northeastern India have brought about changes in forms of plantation labour deployment and organisation. The impact of recent changes on the engagement of women in the tea industry in the major growing regions of Assam and West Bengal is described and explored below.

Tea History and Tea Competition

The tea plantation boom in the nineteenth century that followed the successful marketing of Indian tea at the London Auctions has been characterised as “tea mania.” During this period easy land grants for plantation development under various Wasteland Acts brought in planters and planter capital on a large scale. Tea plantations rapidly spread from the upper Assam region (1840–60), to Darjeeling (1860–60), and the Dooars (1860–80), and through southern India and Ceylon, i.e. Sri Lanka (1880–90). The chief attractions of planter enterprise were the negligible costs of acquiring and running land estates, and the low capital component in the process of manufacturing vis-à-vis high expected profits. However, the principal constraint was the recruitment of a large plantation labour force, which was overcome in different regions by different means. In Assam where early recruitments were done in the Company period, the chief instrument was internal labour indenture – a system also used with success in recruiting Indian “coolie” labour for plantations in the Caribbean, the Indian Ocean, and Fiji. Recruitment of free labour for the Darjeeling and Dooars tea territories was made by labour agents and sardars, using inducements of land availability for cultivation. The kangany system used in south India to recruit Tamil workers for plantations in south India, Sri Lanka, and Malaysia was similar in nature, while plantations in the Cardamom Hills offered seasonal employment to labour drawn from the hill tribes (Wenzlhuemer 2007). This period of labour recruitment, during which some of the worst excesses occurred, has remained largely undocumented.

“Tea mania” lasted till the 1890s, following which the tea glut emanating from the advent of new tea plantations in southern India, Sri Lanka, and Java led to market saturation and an inevitable price fall. In replacement of the old labour-intensive system of hand-manufacture of tea, which had required a huge complement of tea labourers, the first steps towards technical change and mechanisation were seen in the gradual introduction of rolling machines and roll-breaking machines for manufacturing orthodox tea, starting from Assam. While meagre capital investment has made mechanical innovation in the tea industry rather slow, the alternative approach applied for raising tea profitability and productivity has been through organisational change. Thus after the first tea crisis, a number of pioneer planters who had developed the original leases sold out to large corporate tea companies. The large tea estate and the multi-estate tea company were thus born.

Regulation of Tea Enterprise

The first tea regulation emerged in 1903 through the Indian Tea Cess Bill, which provided for a levy on Indian tea exports to be used for the promotion of Indian tea within the country. The Tea Cess Committee was redesignated in 1937 as the Indian Tea Market Expansion Board. Meanwhile, in the wake of worldwide crises in commodity markets during the Great Depression, India, Ceylon, and Java signed an International Tea Agreement in 1933, and effective regulation of the tea industry in India began under the Indian Tea Control Act of 1938, which established the Indian Tea Licensing Committee in order to limit the extent of land areas hitherto available for tea expansion. Succeeding this, a Central Tea Board was established after Independence under provisions of the Central Tea Board Act of 1949, and the Tea Board of India came into existence with the passing of the Tea Act in 1953 (Mukherjee 1978).

While the legislation under which the Indian Tea Board is constituted and the various regulations under Tea Marketing Control are the province of the Union Government in India, implementation of the Plantation Labour Act, 1951, and the plantation rules made thereunder lie within the province of respective State Governments in the tea-growing States. Besides exercising powers relating to grants of land made to plantations and the lease-terms for the same, the States also regulate tea plantations through the monitoring of labour standards.

Because of the isolation of plantation populations in arduous conditions of work, the Plantations Labour Act (PLA) has mandated that decent welfare benefits including drinking water and conservancy be provided by employers to all resident plantation workers compelled by work exigencies to reside within the plantation tea estates. Provision of healthcare with adequately-staffed hospitals and dispensaries with sickness and maternity benefits to workers, and provision of decent housing, worker canteens, and child crèches to working mothers with minor children, along with adequate educational and recreational facilities is also mandated. While these so-called “fringe” or “non-wage” benefits are often cited by planters as part of the obligatory “social costs” that have expanded investment outlays on plantation labour, making Indian tea plantations uncompetitive, their quantum is included notionally in the computation of tea-worker’s wages, thus reducing wage-payments made in cash. In the large tea-growing States of Assam and West Bengal, realisation of PLA benefits has been a major focus for plantation labour movements, while in Tamil Nadu and Kerala that have different state-mandated plantation labour rules, this has been less of an issue.

Several provisions of the PLA have direct implications for women workers. The hours of regular haziri (daily wage) work are limited to 48 hours per week for adults and to 27 hours for non-adults. Beyond these duty hours, thika or double wages are to be paid. Rest intervals of half an hour are mandated after every continuous five-hour work-stretch, while women workers with infant children are entitled to two nursing breaks a day till the child has attained the age of 15 months. In addition to statutory holidays, earned leave with full pay is to be provided to workers at the rate of one day of earned leave for 20 days of work, and all workers suffering illness are entitled to sickness allowance. Women workers were entitled to maternity allowances and benefits under the Maternity Benefit Act of 1961. Besides the statutory provisions of PLA 1951, tea-worker families in Assam and West Bengal under bipartite or tripartite agreement with labour unions, receive subsidised rations, free fuel and dry tea, as a consequence of which they draw lower money wages compared to their counterparts in southern India (GoI 1951).

Welfare benefits under PLA are accessible to permanent resident workers and their bonafide dependents. Subsidised rations are admissible to children of tea-worker families up to the age of 16, provided they depend fully on their parents and are not employed elsewhere. In a subtle gender distinction between dependents of male and female workers, ration benefits extend to the spouses and minor children of employed male workers, but are limited to the immediate family of women workers when their spouse is not a permanent tea worker. PLA medical benefits admissible for women workers are similarly restricted to women workers and their dependent children.

Progress in the implementation of PLA has been tardy both in Assam and West Bengal, because of major weaknesses in the infrastructure for plantation inspections, as well as non-compliance of planters in filing mandatory PLA returns, because of the very minor cash penalties for PLA violations. Shortfalls in decent work conditions as well as in the provision of statutory labour benefits continue to persist.

Gender Roles in the Assam-Dooars Plantations

The estate workforce engaged on large tea plantations in Assam and West Bengal is categorised into standard groups of field workers engaged for upkeep of tea bushes and plucking of tea leaves, and factory workers engaged for processing and manufacture of tea produced by the estate factory. By tradition, the factory workforce has been overwhelmingly male and the field workforce has been dominated by women workers engaged in large numbers for the manual plucking of tea. Although promotional literature extols this as the hallmark of gender equality prevalent on plantations, the truth of the story is quite different.

Women tea workers have been characterised paternalistically in the literature (Griffiths 1967) as “nimble-fingered,” more disciplined and compliant, but through much of plantation history were paid much less compared to male workers. The modes of wage-payment, by which men receive time-rated wages while women receive piece-rated wages upon fulfilling assigned plucking tasks, also create substantive gender discrepancies between male and female tea workers. Male tea workers can expect to progress into supervisory tasks offering higher wages in the course of their careers. Because of a piece-rate payment for their work, women cannot expect to progress to higher wage levels and remain pluckers drawing standard piece-rated wages for the duration of their engagement as workers.

A large number of women are engaged as field workers on labour-intensive tea estates. The attempted cost-cutting by plantation management through reduced engagement of permanent workers and progressive casualisation of fieldwork has inordinately hit women tea workers, who have faced significant reduction in their overall earnings.

Global Restructuring of Tea

Since the era of colonial plantations, the three major plantation crops in India have been tea, coffee, and rubber. There has been dramatic transformation within the ownership of plantations over the last five decades, particularly affecting coffee and rubber plantations, with a dynamic trend towards increase in smallholder units and the decline of large plantations. The smallholder sector has now emerged as the major stakeholder in coffee and rubber. Tea plantations have not undergone the same scale of transformation favouring smallholders, and large integrated tea estates continue to dominate the area under tea (72 per cent) and tea production (80 per cent) in India.

In 2008–09, tea accounted for o.6 million ha (36 per cent) of the total plantation area of 1.6 million ha under these three plantation crops (Viswanathan and Shah 2016), with 82 per cent of the total tea produced being consumed domestically. In contrast, 63 per cent of the coffee produced in India was exported. The share of smallholders in total area and production under tea stood at around 26–28 per cent, while smallholder share in total area and production under coffee was appreciably higher, between 70 to 75 per cent (ibid.). Assam and West Bengal respectively accounted for 56 per cent and 20 per cent of the area under tea in India, and 51 per cent and 24 per cent of the tea produced in India. The three other major tea-growing States in the country were Tamil Nadu (14 per cent area; 16 per cent production), Kerala (6 per cent area; 7 per cent production), and Karnataka (0.4 per cent area; 0.5 per cent production), all in southern India. Collectively, these five major tea-growing States accounted for more than 96 per cent of area under tea and 98 per cent of tea production in India (ibid.).

Restructuring Global Tea Markets

Restructuring within the Indian tea industry has inevitably been spurred by changes occurring in global tea markets, where global tea prices have declined in real terms since the 1970s. Since earliest times, the tea market had been dominated by large sterling tea companies that had secured their economies of scale by operating multiple estates in several tea territories. In close coordination with tea merchants, the large companies were able to protect tea prices by controlling the volume of tea entering the international market, through the consolidated agency of planters’ associations that set out plantation and marketing quotas for their members. This generally helped maintain international tea prices at reasonably high levels by tightly matching the quantity of tea produced to existing market demand. As long as major tea corporates ruled the roost, tea estates occupied the dominant rung of market organisation in the global tea industry, and many international tea corporates had combined business interests in plantation ownership and in global tea marketing. In India, all this began to change after Independence, bringing the tea-marketing chains of global beverage companies to the fore.

As noted earlier, promulgation of various State legislation for acquiring excess estate lands, such as the West Bengal Estates Acquisition Act, 1953 and enforcement of the Foreign Exchange Regulation Act (FERA), 1973, triggered the decline of sterling tea companies in India from the 1970s, followed by their mass exodus to Kenya and eastern Africa, where the new tea industry emerged as a dominant global player. Both Sri Lanka and India reacted variously to this change. Nationalisation of large tea estates in Sri Lanka by the Sri Lanka Freedom Party (SLFP) government under the land reform laws of 1972 and 1975 was reversed in 1992 by re-privatisation under the United National Party (UNP) government, following which the smallholder sector took off, emulating the success of small tea plantations in Kenya (Ganewatta and Edwards 2000).

Smallholder tea operations in India, long in existence in the Nilgiris, initially proliferated through the grant of small land leases to Indian Tamil tea workers repatriated from Sri Lanka under the Shastri-Sirimavo pact, followed by adoption of the small tea garden-bought leaf factory (STG-BLF) model that has since been replicated across many tea-growing areas in India. However, in a peculiarity that separates it from smallholder tea cultivation elsewhere, the Indian STG-BLF model has expanded on non-tea lands culled from crop-farming operations and replanted with tea, while the traditional estate mode of manufacture continues to coexist. Based on the principle that “many hands make light work,” the STG model has been instrumental in expanding virtual tea productivity because of the invisibility of the many hands engaged in tea-plucking. However, its emphasis on maximising quantity of green leaf production does not translate immediately into tea quality, where estate production continues to hold its own.

The price-impetus for such changes has been provided by restructuring within international tea markets, caused by the declining importance of estate companies in favour of tea corporates and international tea blenders. Along with changes in international tea marketing, these have changed the hierarchical importance of different tea-producing countries, and placed Kenya at the fore.

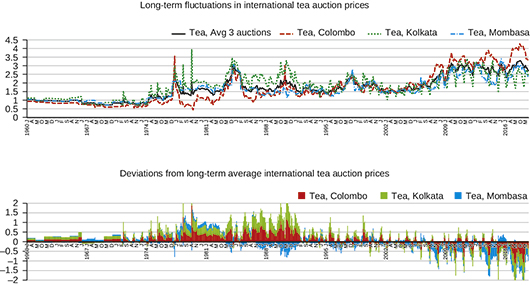

Commodity trade trends in global tea from the World Bank commodity database are illustrated in Figure 1, which compares prices in the Mombasa, Colombo, and Kolkata tea auctions. From 1706 to 1998, global price trends for tea were set at the London Tea Auction, with quick price responses from the Calcutta Tea Auction, followed by the auctions at Colombo and Mombasa. Mombasa was a relatively late addition to the global tea auction system, with Kenya Tea Auctions initially established in 1956 at Nairobi, and shifted to the port-city of Mombasa in 1969 (EATTA 2018). From 1992, the Mombasa Tea Auction became dollar-denominated with full convertibility, driving it into a position of price leadership over global tea prices. Sensitivity analysis thereafter indicates that Mombasa tea auction prices were followed in suit by the Colombo Auction, while the Calcutta Tea Auction followed at a distant third.

Figure 1 Long-term fluctuations and deviations from the long-term average in international tea auction prices in USD per kg

Source: Data drawn from the World Bank Commodity Price Data, The Pink Sheet (2018).

Restructuring of Plantations and the Plantation Workforce

Tea grants and attached waste land grants during the colonial era were held under extremely favourable long-lease terms. In Darjeeling district in West Bengal, nearly half the tea estates in 1951 were held under freehold or revenue-free terms. Attachment of additional land grants to tea estates were made to provide homesteads and marginal farmland to migrating tea labour communities. In 1953, along with rationalisation of land rents, the West Bengal Estates Acquisition Act sought to replace these varying land dispensations with a uniform renewable lease of 30 years, besides resuming such lands within the grant that were being used for purposes other than growing tea. The intention was to prevent tea estates from functioning as “mini zamindaris” (Ghosh 1987, p. 84). This was vigorously contested by the sterling estates, as this stripped them of residual power as landlords, turning them into tenants of the Government.

Based on a survey of tea estate lands executed by the Settlement Directorate in the 331 tea estates in existence in the 1950s, the original Tea Garden Advisory Committee constituted under the West Bengal Estates Acquisition Act, 1955 had recommended the resumption of surplus lands in the case of 225 tea estates (ibid., p. 81). Implementation of this recommendation was delayed by 16 years till the Calcutta High Court judgment on the Malhati Tea Syndicate case cleared the way in 1970. Combined with regulations under the Foreign Exchange Regulation Act (FERA), which diluted foreign equity in the tea industry to 40 per cent, the period following the mid-1970s saw the departure of the London-incorporated sterling companies that had dominated the Indian tea sector for over 100 years, as well as the advent of new Indian tea-group companies.

After the removal of legal encumbrances and resumption of surplus tea estate lands during the mid-1970s, the tea industry in West Bengal and Assam often sought additional land grants from the Government for expanding tea cultivation. Following the tea boom from the mid-1980s onwards, the tea industry again sought releases of additional Government land for expanding plantations. In acknowledging the difficulty of securing forest lands for plantation purposes after the Forest Conservation Act, 1980 (ITA 1986, p. 2), the industry noted in reference to Assam that estate lands allotted to local farming populations in the State were unsuited to paddy cultivation. To circumvent legal problems that would arise if these lands were given over to tea estates, the idea of parcelling out such lands to small growers for tea cultivation was conceived.

In the old tea-growing regions of Assam and northern West Bengal where large tea estates were concentrated, the presence of small tea growers (STG) is relatively new. Progressive assignment of ceiling-surplus homestead lands to landless farmers under the land redistribution policy of West Bengal from the late 1970s had left little land in non-traditional areas to be granted for new tea leases. In the traditional growing areas of the Darjeeling hills, the Terai and the Dooars, conversion of forests into revenue lands had reached a standstill after Independence. All large tea estates had been established well before the 1930s.

Three-fourths of the 49,397 ha of vested lands transferred for homesteads and cultivation to 0.2 million landless beneficiaries in Darjeeling and Jalpaiguri were located in Jalpaiguri district. While the unit size of redistributed land was small (less than 0.3 hectare), the land units transferred in Jalpaiguri were twice as large as the average land transfer under land reforms across the State, providing an impetus to rural migration to Darjeeling and Jalpaiguri districts. By 1996, nearly 70 per cent of the farmers in the two tea-growing districts were marginal farmers cultivating an average plot of 0.5 ha. Nearly 56 per cent of land transfers in the two tea-growing districts had been made in the later phase of land reforms between 1980 and 1990 (Chakraborti et al. 2003). During this period of aggressive land reforms after 1977, assignment of government-held vested land for other non-agricultural and commercial purposes was not an alternative.

Issues of Tea-Worker Deployment and Wages

Plantation wages in Assam and West Bengal are determined by bipartite wage agreements between employers’ associations and labour unions, or tripartite agreements with additional Government arbitrage according to the Plantation Labour Rules made by the respective State, under provisions of the Plantation Labour Act, 1951. Even though tea wages are a State subject, the Minimum Wages Act, 1948 had provided for fixing minimum wages for tea labour. Not until 2006 were minimum wages for tea workers actually fixed by the State Governments of Tamil Nadu, Karnataka and Kerala, which now stand at Rs 310, Rs 263, and Rs 241, respectively. Meanwhile, the respective State Governments of the large tea-growing States of Assam and West Bengal, where tea wages are lowest, are in the process of negotiating minimum wages for tea workers.

The modes of formulation for wages have been subject to longstanding debate, from the Royal Commission on Labour, 1931 to the First and Second National Commission of Labour (1969 and 2002). Since by definition, minimum wages are applicable to unskilled casual labour, two alternative wage concepts that have received some attention are fair wages and living wages (National Commission on Rural Labour 1991).

While a fair wage would provide for a modicum of education, healthcare, and amenities over and above the statutory minimum wage, the living wage would be at a level that provided standards of comfort over and above necessities like food, shelter, and clothing to workers (ibid.,

In tea plantations where family labour has been the prevalent practice since inception, the standard mode of wage fixation by the agreements has been to fix the joint earnings of two working spouses within a family at a level that will collectively provide for a family of four. Each earning spouse has thus been paid enough support for one and one-half consumption units per family. Wage stresses emerge particularly in labour households headed by widowed or single women whose wage earnings prove inadequate to support their family. Non-wage benefits such as subsidised food rations are also given for dependent children, but are unavailable to male spouses who do not work on the plantation. Other members from tea labour households engaged temporarily for seasonal plucking as casual or bigha/bustee labour are also not entitled to non-wage benefits.

Prior to the Equal Remuneration Act, 1976 and the Child Labour (Abolition and Regulation) Act, 1986, women, adolescents, and child workers from Indian plantation labour families constituted a cheap labour pool available to estate managements for engagement as field workers, in direct continuity with the family mode of labour common on tea plantations. While daily-rated permanent or hazira workers were available for work around the year, other casual workers were engaged during seasons of peak labour demand. By securing statutory non-wage benefits for worker families residing in labour lines within the plantation, the Plantation Labour Act, 1951 gave rise to a new work category of “outside” workers. As outside workers only drew wages and no non-wage benefits, they quickly became a low-cost option for tea plantations. As temporary bigha workers engaged from outside the plantation were engaged at prevailing wages only during peak plucking seasons and did not draw PLA non-wage benefits for themselves or their dependents, they became a low-cost labour option for plantations. Creation of labour categories of different descriptions among plantation workers encouraged the development of a highly segmented labour market. Performing the same tasks as resident workers, the increased employment of casual labour in increasing numbers significantly reduced wage costs on tea plantations. Temporary workers drawn from outside the plantation are not entitled to regular work engagement and have thus become a floating labour reserve that can be engaged and laid-off at will.

Table 2 Changes in the deployment of the workforce in tea plantations, by region and type of employment, 1996–2004 in number

| Region | 1996 | 1997 | 1998 | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 |

| All workers in tea estates | |||||||||

| Assam | 590,968 | 591,036 | 598,825 | 596,943 | 602,531 | 611,063 | 619,663 | 619,322 | 617,518 |

| West Bengal | 293,093 | 282,806 | 286,967 | 251,012 | 253,459 | 255,569 | 259,182 | 260,336 | 262,672 |

| Northern India | 903,204 | 892,556 | 904,654 | 864,916 | 873,058 | 883,450 | 895,900 | 896,272 | 896,717 |

| Tamil Nadu | 132,703 | 143,378 | 145,183 | 245,379 | 255,790 | 267,665 | 275,723 | 268,351 | 266,027 |

| Karnataka | 5,885 | 4,642 | 281 | 3,680 | 3,789 | 3,837 | 3,953 | 4,403 | 4,508 |

| Kerala | 99,235 | 97,592 | 96,465 | 74,496 | 77,086 | 77,198 | 79,524 | 87,184 | 90,358 |

| Southern India | 237,827 | 245,612 | 241,929 | 323,555 | 336,665 | 348,700 | 359,200 | 359,938 | 360,893 |

| All India | 1,141,031 | 1,138,163 | 1,146,583 | 1,188,471 | 1,209,723 | 1,232,150 | 1,255,100 | 1,256,210 | 1,257,610 |

| Resident workers in tea estates | |||||||||

| Assam | 449,981 | 446,288 | 451,896 | 423,473 | 423,437 | 426,807 | 432,839 | 457,942 | 464,755 |

| West Bengal | 255,140 | 243,887 | 247,289 | 198,724 | 198,849 | 199,757 | 202,579 | 216,090 | 220,332 |

| Northern India | 716,123 | 700,467 | 709,352 | 632,929 | 633,036 | 637,049 | 646,052 | 684,914 | 696,119 |

| Tamil Nadu | 109,331 | 119,200 | 120,532 | 131,157 | 132,212 | 133,114 | 137,122 | 154,012 | 160,406 |

| Karnataka | 5,602 | 4,366 | 4,345 | 3,440 | 3,464 | 3,485 | 3,591 | 3,980 | 4,123 |

| Kerala | 81,753 | 79,333 | 78,400 | 67,093 | 67,515 | 67,541 | 69,576 | 79,411 | 83,102 |

| Southern India | 196,685 | 202,899 | 203,277 | 201,690 | 203,191 | 204,140 | 210,289 | 237,403 | 247,631 |

| All India | 912,809 | 903,366 | 912,629 | 834,619 | 836,227 | 841,189 | 856,341 | 922,317 | 943,750 |

| Outside workers in tea estates | |||||||||

| Assam | 140,987 | 144,748 | 146,929 | 173,470 | 179,094 | 184,256 | 487,670 | 512,790 | 519,635 |

| West Bengal | 37,989 | 38,919 | 39,678 | 52,288 | 54,610 | 55,812 | 214,715 | 228,317 | 232,532 |

| Northern India | 187,081 | 192,089 | 195,302 | 231,987 | 240,022 | 85,701 | 714,138 | 753,098 | 764,305 |

| Tamil Nadu | 23,372 | 24,178 | 24,651 | 114,222 | 123,578 | 134,551 | 149,446 | 166,362 | 172,782 |

| Karnataka | 283 | 276 | 0 | 240 | 325 | 352 | 3,591 | 3,980 | 4,123 |

| Kerala | 17,386 | 18,259 | 18,065 | 7,403 | 9,571 | 9,657 | 75,498 | 138,662 | 89,032 |

| Southern India | 41,141 | 43,613 | 42,716 | 121,865 | 133,474 | 144,560 | 228,535 | 255,678 | 265,937 |

| All India | 228,222 | 234,802 | 238,018 | 353852 | 373496 | 390961 | 942673 | 1008776 | 1030242 |

| Outside permanent workers in tea estates | |||||||||

| Assam | 48,750 | 50,519 | 51,261 | 54,187 | 54,463 | 54,568 | 432,839 | 457,942 | 464,755 |

| West Bengal | 10,756 | 10,808 | 10,980 | 12,036 | 12,083 | 12,110 | 202,579 | 216,090 | 220,332 |

| Northern India | 61,686 | 63,017 | 63,951 | 67,298 | 67,674 | 67,804 | 646,052 | 684,914 | 696,119 |

| Tamil Nadu | 9,256 | 10900 | 11,108 | 12,066 | 12,215 | 12,292 | 137,122 | 154,012 | 160,406 |

| Karnataka | — | — | — | — | — | — | 3,591 | 3,980 | 4,123 |

| Kerala | 8,835 | 9242 | 9,130 | 5,655 | 5,948 | 5,928 | 69,576 | 79,411 | 83,102 |

| Southern India | 18,091 | 21042 | 20,238 | 17,721 | 18,163 | 18,220 | 210,289 | 237,403 | 247,631 |

| All India | 79,777 | 83,159 | 84,189 | 85,019 | 85,837 | 86,024 | 856,341 | 922,317 | 943,750 |

| Outside temporary workers in tea estates | |||||||||

| Assam | 92,237 | 94,229 | 95,668 | 119,283 | 124,631 | 129,688 | 54,831 | 54,848 | 54,880 |

| West Bengal | 27,233 | 28,111 | 28,698 | 40,252 | 42,527 | 43,702 | 12,136 | 12,227 | 12,200 |

| Northern India | 125,395 | 129,072 | 131,351 | 164,689 | 172,348 | 17,897 | 68,086 | 68,184 | 68,186 |

| Tamil Nadu | 14,116 | 13,278 | 13,543 | 102,156 | 111,363 | 122,259 | 12,324 | 12,350 | 12,376 |

| Karnataka | 283 | 276 | — | 240 | 325 | 352 | — | — | — |

| Kerala | 8,551 | 9,017 | 8,935 | 1,748 | 3,623 | 3,729 | 5,922 | 59,251 | 5,930 |

| Southern India | 23,050 | 22,571 | 22,478 | 104,144 | 115,311 | 126,340 | 18,246 | 18,275 | 18,306 |

| All India | 148,445 | 151,643 | 153,829 | 268,833 | 287,659 | 304,937 | 86,332 | 86,459 | 86,492 |

| Bonafide dependents of resident workers | |||||||||

| Assam | 651,014 | 658,660 | 668,629 | 652,562 | 652,393 | 653,175 | 131,993 | 106,532 | 97,883 |

| West Bengal | 361,265 | 346,528 | 351,376 | 326,214 | 325,814 | 326,054 | 44,467 | 32,019 | 30,140 |

| Northern India | 1,023,399 | 1,016,251 | 1,031,141 | 989,351 | 988,777 | 989,788 | 181,762 | 143,174 | 132,412 |

| Tamil Nadu | 188,203 | 157,833 | 161,189 | 162,427 | 163,173 | 163,422 | 126,277 | 101,989 | 93,245 |

| Karnataka | 589 | 666 | 672 | 680 | 682 | 684 | 362 | 423 | 385 |

| Kerala | 62,636 | 65,606 | 65,035 | 65,993 | 65,873 | 65,930 | 4,026 | 1,848 | 1,326 |

| Southern India | 251,428 | 224,105 | 226,896 | 229,100 | 229,728 | 230,036 | 130,665 | 104,260 | 94,956 |

| All India | 1,275,827 | 1,240,356 | 1,258,037 | 1,218,451 | 1,218,505 | 1,219,824 | 312,427 | 247,434 | 227,368 |

| Resident workers and dependents | |||||||||

| Assam | 1,241,982 | 1,249,696 | 1,267,454 | 1,249,505 | 1,254,924 | 1,264,238 | 751,656 | 725,854 | 715,401 |

| West Bengal | 654,358 | 629,334 | 638,343 | 577,226 | 579,273 | 581,623 | 303,649 | 292,355 | 292,812 |

| Northern India | 1,926,603 | 1,908,807 | 1,935,795 | 1,854,267 | 1,861,835 | 1,873,238 | 1,077,662 | 1,039,446 | 1,029,129 |

| Tamil Nadu | 320,906 | 301,211 | 306,372 | 407,806 | 418,963 | 431,087 | 402,000 | 370,340 | 359,272 |

| Karnataka | 6,474 | 5,308 | 953 | 4,360 | 4,471 | 4,521 | 4,315 | 4,826 | 4,893 |

| Kerala | 161,871 | 163,198 | 161,500 | 140,489 | 142,959 | 143,128 | 83,550 | 89,032 | 91,684 |

| Southern India | 489,255 | 469,717 | 468,825 | 552,655 | 566,393 | 578,736 | 489,865 | 464,198 | 455,849 |

| All India | 2,416,858 | 2,378,519 | 2,404,620 | 2,406,922 | 2,428,228 | 2,451,974 | 1,567,527 | 1,503,644 | 1,484,978 |

| Dependency ratio among resident workers | |||||||||

| Assam | 1.102 | 1.114 | 1.117 | 1.093 | 1.083 | 1.069 | 0.213 | 0.172 | 0.159 |

| West Bengal | 1.233 | 1.225 | 1.224 | 1.300 | 1.285 | 1.276 | 0.172 | 0.123 | 0.115 |

| Northern India | 1.133 | 1.139 | 1.140 | 1.144 | 1.133 | 1.120 | 0.203 | 0.160 | 0.148 |

| Tamil Nadu | 1.418 | 1.101 | 1.110 | 0.662 | 0.638 | 0.611 | 0.458 | 0.380 | 0.351 |

| Karnataka | 0.100 | 0.143 | 2.391 | 0.185 | 0.180 | 0.178 | 0.092 | 0.096 | 0.085 |

| Kerala | 0.631 | 0.672 | 0.674 | 0.886 | 0.855 | 0.854 | 0.051 | 0.021 | 0.015 |

| Southern India | 1.057 | 0.912 | 0.938 | 0.708 | 0.682 | 0.660 | 0.364 | 0.290 | 0.263 |

| All India | 1.118 | 1.090 | 1.097 | 1.025 | 1.007 | 0.990 | 0.249 | 0.197 | 0.181 |

Source: Computed from Tea Statistics, Tea Board of India, various years.

The tea industry in India has been comprehensively documented between 1955 and 2004, when the Tea Board of India regularly published its twin compendia, Tea Statistics and Tea Digest. From 1998 onwards, the Tea Board began to include production data for small STG tea gardens below 25 acres (10.2 ha), and as the tea databases grew in size, regular publication of the data compendia soon ceased. In 2004, the last year for which the Tea Board’s Tea Statistics are available, the total field workforce on Indian tea plantation numbered around 1.3 million, with a 9.3 per cent increase over the workforce strength in 1996. Of the total tea workforce, 71 per cent was engaged on plantations in northern India, primarily Assam and West Bengal, while 39 per cent was engaged on plantations in southern India. However, in comparative terms, absolute attrition in the tea workforce in northern India was led by a 12 per cent decline in the tea workforce in West Bengal. The 8-year decline was most marked in the case of resident tea workers, which declined by 35 per cent over the period, even as the all-India figure increased by 3.3 per cent, with most of the accretion occurring in southern India. This was followed by increases of over 90 per cent in the deployment of outside permanent workers throughout India, with the accretion in West Bengal alone amounting to over 95 per cent.

In sum, the casual workforce engaged on tea plantations in India increased by over 0.8 million workers between 1996 and 2004, with the bulk of labour casualisation occurring in southern India (0.2 million) and West Bengal (0.2 million). On account of an overall decline in resident permanent workers in plantations in northern India, the number of bonafide dependents also fell from 1 million in 1996 to 0.1 million. Thus at an all-India level, the number of resident workers and bonafide dependents entitled to receive PLA non-wage benefits was curtailed in absolute terms from 2.4 million to 1.5 million between 1996 and 2004, while in Assam and West Bengal alone, the number of PLA non-wage beneficiaries was slashed by nearly 0.9 million consumption units.

In the late 1980s, before the advent of globalisation, resident workers comprised over 80 per cent of the total tea labour force. By 2004, their overall proportion within the aggregate labour force had come down to half through 75 per cent attrition in resident labour positions, while the remainder of the aggregate tea workforce comprised outside workers, among whom 90,000 were enagaged on casual contracts. Thus, although the aggregate tea labour force in India grew by more than 0.27 million in the 15-year period between 1985 and 2000, the increase in resident tea workers amounted to only around 59,000, indicating the massive scale of labour casualisation that occurred in the tea sector after liberalisation.

In tea plantations in Assam and West Bengal, which are generally located at a distance from urban settlements and dominated by the large-scale tea estates sector, the impact of labour casualisation on the tea workforce has been particularly marked. The proportion of outside bigha workers engaged has risen from 12 per cent to nearly 89 per cent on tea estates in West Bengal, and from 22 per cent to 84 per cent on plantations in Assam, between 1985 and 2004. Keeping in mind that tea estates in northern India are very large and located on forest peripheries at immense distances from the sites of general habitation, workers engaged in casual employment on tea plantations do not have other local sources of alternative work. Meanwhile, although money wages in the Assam and West Bengal tea plantations are negotiated by bipartite or tripartite agreements, their levels continue to be much lower than wages paid to tea workers in southern India. Tea workers in Assam and West Bengal are entitled instead to non-wage benefits under PLA 1951, such as subsidised fuel and rations. On the other hand, tea workers on plantations in southern Indian are paid a scalable dearness allowance in lieu of non-wage benefits in addition to the basic worker wage, that is, the allowance is scaled upwards periodically to compensate for increases in the cost of living.

Plantation workers recruited from outside the tea estates and their dependents are not entitled to these non-wage benefits. Hence, attrition of the permanent tea workforce through reorganisational devices such as mass casualisation has drastically brought down social costs previously borne by the tea industry, unmatched by any long-term increase in average tea prices. In a classic characterisation of the Prebisch-Singer hypothesis, the estate owners secure profits by cutting down on the wage bill, rather than through aggressive marketing and better price realisation. The inability of tea labour to resist attrition in numbers and real wages has even led, in times of great financial stringency, to starvation deaths.

Reorganisations in the Indian Tea Sector

Evoluion of Plantations in India

Large-scale changes in ownership in the India tea industry occurred after the enactment of legislation such as the Plantation Labour Act in 1951 and the Foreign Exchange Regulation Act (FERA) in 1973. Many sterling tea companies had already departed Indian shores for greener pastures in East Africa (Wickizer 1957) while persuading others to find Indian partners to buy out a part of their equity. While growing tea might technically be described as a monocultural tree-farming operation, the estate sector also represents a mode of commercial organisation for large-scale cultivation of tea. Not designed specifically for commercial tea plantations, the organisational system was borrowed from the nineteenth century sugar and cotton plantations of the New World. The estate system underwent a process of continuous evolution on the large tea plantations of Assam and the Dooars, before settling into a model of rigorous supervision of tea labour on plantations, coupled with a tightly controlled agronomy. Once this was set, the new estate model was rapidly replicated in many other tea areas in India and abroad. Essentially, the estate model worked splendidly in minimising labour costs, fostering a highly exploitative labour system over which early planters exercised coercion through quasi-legal powers. On account of the sheer size of the tea tracts, remnants of this coercive planter power survive on large tea plantations today, with little civil restitution available.

During its most regressive period, tea production was undertaken on an industrial scale through internal indenture in Assam, to supply the needs of distant colonial metropoles. Eventually the early pioneer tea plantations evolved into a large corporatised model, in which the relative positions of the estate owners versus plantation labourers were highly uneven. Rather than being “paternalistic” as colonial writers have pointed out (Griffiths 1967), planters were ruthless in coercing labour in their pursuit of profit. Labour regulation through legislations enacted after Independence failed to achieve desired results, because of huge disparities between the powers of planters versus labour unions. Instead of achieving minimum wages as provided for under the Minimum Wages Act of 1948, tea workers had to settle for vastly inferior wage agreements where social welfare components were priced notionally as wages in kind, considerably reducing the money wage to be paid. Tea estate workers thus received the lowest organised sector wages, compared to other plantation crops as well as the mining sector, which was subsequently nationalised.

Compared to the small tea grants made to pioneer planters in Assam and the Dooars, tea grants became progressively larger as investor interest increased, prompting planters who had pooled their resources to form registered tea associations (GoWB 2000). This is particularly visible in the Dooars, where a large land tract annexed from Bhutan was specifically dedicated to tea grants. As the capital of tea companies expanded and estate areas also grew, some of them began to buy out individual planters in order to consolidate their lease, particularly during tea slumps. Cross-holding of tea estates in multiple tea regions was first found when the consolidated Assam Dooars Tea Company acquired several tea leases in the Dooars. New leases thereafter were generally taken out by tea corporates.

Consolidation of tea holdings in the early phase allowed the achievement of production economies of scale, and expanded marketing economies by limiting transaction costs of the tea trade. Similar size and scale dynamics, which are also noticed in several plantation commodities produced in other parts of the world, including cotton and sugarcane (Shlomowitz 1984), represented the ability of the producing industry to meet the changing demands of world trade. For tea plantations in India, this process was so successful that by the late 1880s Indian-made tea had supplanted Chinese tea from the London market. By producing tea at a low cost, the large-scale estate system in India also standardised the quality of Indian tea, enabling tea to become a commodity for mass consumption.

Besides organisational innovations in the scale of ownership and production, the process of tea manufacture essentially remained the same. Beyond mechanisation of processing at tea factories, tea production remained labour-intensive. This allowed the use of artisanal processes of plucking that maximised product quality. Such processing and production methods remain substantially untransformed in the Assam and West Bengal tea estates even today, even though the corporate ownership of the estates has grown substantially after Independence.

During the departure of sterling tea companies, several diversified Indian corporate houses made their forays into tea, expanding their interests by setting up semi-independent tea divisions and affiliates. Even so, most Indian tea corporates are closely-held and even those with market-listed shares see little trading in those shares. An overwhelmingly large number of tea companies in northern India are closely-held private limited operations, indicating that their corporate status is more a business convenience than a device for mobilising additional capital. With more capital being deployed for corporate mergers and acquisition, very little planter capital today is applied to improve agronomic conditions in the Indian tea industry.

Intra-Industry Innovation: Tea Estates Versus Small Tea Growers

While organised tea corporates in India may hold periodic increases in tea wage and non-wage benefits as responsible for falling profits in the tea sector (Tharian 1984), this is a largely circular argument. As plantation production has been highly labour-intensive from its inception, the plantation workforce is necessarily large, while capital outlays are traditionally low. Although tea companies invariably declared high dividends regardless of price buoyancy, they failed to build adequate cash reserves out of profits, relying excessively instead on bank finance (Mukherjee op. cit.). Financial situations are even more stringent on estates in Assam and the Dooars, where tea production reaches a standstill for four months in the winter. To tide the estate over during the lean season, tea companies hypothecate their expected first flush tea crop to commercial banks in lieu of bridge credit. Whenever financial expectations fail to materialise because of inclement weather or low price realisation, tea corporates point out that Indian tea has progressively become uncompetitive because of “social burdens” placed on planters in the form of non-wage payouts to workers.

Large tea estates in Assam and the Dooars form contiguous fiefdoms, with tea cultivated over huge land tracts. Open labour markets have not developed as a result. With tea workers bound to servitude on tea estates, even rudimentary healthcare, housing, and education depend on the whims of the estate management. By the 1980s, when the sterling tea companies that were part-controlled by big international tea blenders had departed from India, global tea prices began to drift downwards in real terms. Unlike in the past when corporate dividends and their forward linkage with the global beverage industry had continuously buoyed tea companies, tea bottom lines started slipping. With their new corporate owners more occupied in skimming tea profits for business investment elsewhere, perceptions grew that the archetypal integrated tea estate was beginning to outlive its utility.

The changes that followed were of an organisational kind. While the tea boom during the 1980s had centred around the provision of additional plantation lands, the focus was now on revenue lands that had previously been resumed from the estates. The idea of parcelling out these lands for smallholder tea cultivation, preferably by ex-tea workers living on the estate fringe, hence took shape. By organising “project gardens” in close vicinity through transfers of technology and supply of planting materials, large estates were able to secure outside sources of green leaf on buy-back terms for processing at their factories, without having to increase social payouts to their own workers. Thus the small tea growers (STG) co-opted by the estate sector became yet another low-cost segment for increasing tea production in India.

A major cause of the commercial crisis in the Indian tea sector has been the inability of tea exports to increase in tandem with tea production. Over seven decades since 1948–49, tea production in India has multiplied manifold, but Indian tea exports have stagnated at about 200 million kg per annum. The creation of the Tea Board of India under the Tea Act in 1953 for tea promotion has achieved very little in terms of augmenting tea exports. With stagnant tea exports, the bulk of Indian tea is absorbed by the domestic market that has grown phenomenally over the same period.

Sluggishness in Indian tea exports has been mistakenly attributed to the inability of Indian tea production to keep up with the needs of the domestic market, thus limiting the quantity of tea available for export. Other limiting factors, such as tea quality, chemical constituents of processing, market imperfections, and emergence of new international tea competition are ignored. Unlike the era of sterling tea companies when competitive international pricing was preserved through careful regulation of annual tea output, the Tea Board has ascribed the sluggishness of tea exports to the crisis of underproduction. Constant efforts have been made to raise tea output in the country (Bhowmik 1991). In 1983, for instance, the Tea Development Plan formulated by the Tea Board projected a minimum production target of 950 million kg to be realised in 15 years, based on a projected 28 per cent share for India in the global tea trade, with per capita domestic tea consumption projected at 0.6 kg per annum (ITA 1983). Provisional tea export figures of 216.8 million kg in 2016 would put India’s share in global tea exports much lower, at 12.2 per cent. The size of the domestic tea market that year would thus be estimated at 1,022.4 million kg.

Appropriate questions might be asked about whether shortfalls in Indian tea exports can be legitimately attributed to the aggressive growth of domestic tea demand, or whether the growth of the domestic tea market is actually the fait accompli through which non-exportable tea output is absorbed. With low realisation of export earnings, and because domestic tea consumers are more price conscious and less quality conscious, the quality of tea produced in India has undergone a commensurate decline in a bid to keep production costs at a minimum in order to preserve levels of corporate profits.

The STG model therefore emerged as a solution to persisting problems of the tea industry. By outsourcing green tea from independent tea farming operations located outside the plantations, tea producers were able to delink tea production from the tea workforce. Engagement with STG growers enabled tea producers to generate profits on a new bottom line, in which “social costs” were considerably low. The fallouts of this new “profitability” were passed down to the working class, with tea workers across India experiencing a major fall in real wages. The engagement with STGs offered another strategy for tea manufacturers to expand profits by delinking wages from work and working around PLA provisions. Under the terms of the Plantation Labour Act (PLA), 1951, smallholder tea gardens below 25 acres (10.2 ha) in size, which employ less than 15 workers are not classified as plantations. The STGs therefore operate beyond the pale of PLA provisioning for housing, healthcare, education, and other non-wage benefits to plantation workers. Further, STG operations have very low production costs as they fall under the category of farming operations outside the organised sector. Many are small-sized family farming enterprises, with minimal engagement of wage workers from outside. By operating within the traditional ambit of family labour where all family members jointly contribute to work, the STG model reinforced the use of family-based labour for tea production, while lowering attendant costs. Even gross rights violations such as labour exploitation and use of child labour go unnoticed on smallholder tea gardens.

Restructuring the tea sector in India on the lines of the STG model thus brought the misery of plantation labour into conflict with the misery of the poor peasantry. Because of the adverse impact on real earnings of workers, one of the most pressing demands of the labour movement, that is, the fulfilment of PLA provisions, was accorded low priority on corporate plantations. With more than half the estimated 2 million strong tea workforce in India comprising women tea pluckers, it is this section of plantation women that has been particularly hard hit.

Fallouts for Plantation Women

The high level of female work participation in tea plantations is a historical relic of the plantation system based on employment of the family labour unit. The switch to the smallholder mode of tea production invisibly drew the family labour unit into the tea production chain without formally engaging its labour. Family-based application of labour had traditionally served to tie plantation families to the plantation. As women plantation workers legally drew a lower wage than their male counterparts until 1976, use of plantation women for field labour indicated labour substitution through the employment of cheaper women’s labour. The practice also helped the estate management in bidding down wage demands made by workers.

In view of the Tea Board’s projections for augmented tea production in India, there was a pressing need to raise tea productivity on the large plantations of Assam and the Dooars. However, because of the high labour intensity of plucking operations, wage costs on the estates would expand commensurately with their need for women pluckers. Two modes of manual plucking have usually been resorted to on the Assam and Dooars tea estates. Fine-plucking by skilled hands had traditionally ensured better tea quality and higher price realisations for the orthodox tea produced on large plantations. For the more price-conscious market segment, coarse-plucking was undertaken, which took in more of the stem and leaves. While tea produced though coarse-plucking process was of lower quality and would fetch lower prices, estate managements could maximise green leaf output without engaging the same number of pluckers. Alternatively, since the hiring of outside workers not on the permanent estate payroll reduced wage costs, permanent women workers who retired were not replaced. As a new generation of temporary and casual pluckers stepped into their place, women’s work on the tea estates became marginalised.

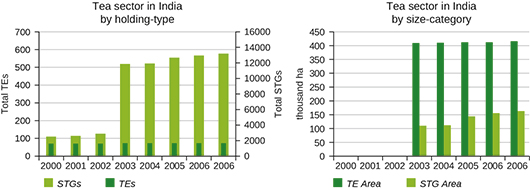

Figure 2 Growth of smallholder tea gardens in India, by type of holding and aggregate land-size, 2000–06 in number and thousand ha

Notes: 1. TE stands for tea estates.

2. STG stands for smallholder tea gardens.

Source: Tea Board of India, 2008.

Another important factor that has marginalised economic rewards to plantation women is the practice of paying piece-rated wages to women pluckers as against the time-rated wages paid to male workers. Each estate plucker has to fulfil an assigned plucking task each working day, without receiving any benefits for the length of her experience. While male tea workers can expect to progress through the ranks to the level of sub-staff, no seniority dividends accrue to plantation women. Once recruited as a plucker, the woman remains a plucker, performing the same task and earning the same wage through the duration of her working life.

Takahashi and Mani (2004, p. 4) estimate that a woman tea plucker has to complete 900 plucking movements with her hands, in order to assemble a kilogram of green tea leaf. This would vary according to the quality of plucking demanded, with fine plucking requiring many more hand movements. Women pluckers also have to traverse uneven terrain carrying loads of 24-26 kg per day. The wages paid to women plantation workers do not reflect the arduousness of their work.

With identical piece-rates applying to women pluckers, irrespective of whether they are hazira (permanent) or bigha (temporary) workers, wages on the Assam and Dooars plantations have been designed to extract the maximum time contribution per women worker, automatically translating into higher plantation productivity, without meaningfully compensating her for the additional work-time she contributes. Meanwhile, since the number of women pluckers deployed varies according to season, it is meaningless to speak of worker productivity as a universal attribute of efficiency for all plantations.

Information on the growth of smallholder tea plantations across various tea regions of India remained opaque till the Tea Board began to include data on the STG sector from 1998. Nevertheless, establishment of the first smallholder plantations supplying green tea to estate factories in the Nilgiris district of Tamil Nadu has been recorded from the 1920s. After the repatriation of Indian Tamil tea workers from Sri Lanka in the 1960s, a new round of tea expansion occurred in traditional non-tea areas in Tamil Nadu, with processing support from independent bought-leaf factories (BLFs). Following the tea boom of the 1980s and the resulting Tea Development Plan, the STG-BLF cluster model began to spread to other tea-growing States, albeit slowly at first. In the large tea tracts of Assam and the Dooars where the alternative “project garden” approach had evolved by centering around existing estate factories, the expansion of BLFs was slow until the post-liberalisation policies of the 1990s. Thereafter, the growth of the STG sector increased rapidly, particularly in Assam.

Changes in the tea workforce over the post-liberalisation period from 1996 to 2004 – the last year for which Tea Board data are publicly available – are documented in Table 3. The aggregate tea workforce in Assam has grown in marked opposition to the downscaling of the workforce in West Bengal. Similar opposite trends are seen in the expanded tea workforce in Tamil Nadu versus the marked downscaling in Kerala and Karnataka. However, as the growth of the tea workforce in southern India was strong enough to counteract the decline in northern India, the overall tea workforce in India grew over this period. Significantly, the growth of hazira workers in Assam was more than offset by their decline in West Bengal. In southern India, despite the steep decline in Kerala, the permanent tea workforce as a whole grew because of marked growth in the Nilgiris in Tamil Nadu.

Table 3 Changes in tea workforce on plantations in India, by type of worker and region,1996–2004 in number

| All tea workers | Change | |||||||||

| Tea regions | 1996 | 1997 | 1998 | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 1996–2004 |

| Northern India | ||||||||||

| Assam | 590,968 | 591,036 | 598,825 | 596,943 | 602,531 | 611,063 | 619,663 | 619,322 | 617,518 | 26,550 |

| West Bengal | 293,093 | 282,806 | 286,967 | 251,012 | 253,459 | 255,569 | 259,182 | 260,336 | 262,672 | −30,421 |

| Others | 19,143 | 18,714 | 18,862 | — | — | — | 17,055 | 16,614 | 16,527 | −2,616 |

| Northern India | 903,204 | 892,556 | 904,654 | 864,916 | 873,058 | 883,450 | 895,900 | 896,272 | 896,717 | −6,487 |

| Southern India | ||||||||||

| Tamil Nadu | 132,703 | 14,337 | 145,183 | 245,379 | 255,790 | 267,665 | 275,723 | 268,351 | 266,027 | 133,324 |

| Karnataka | 5,885 | 4,642 | 281 | 1,945 | 1,958 | 1,952 | 2,011 | 2,381 | 2,464 | −3,421 |

| Kerala | 99,235 | 97,592 | 96,465 | 3,680 | 3,789 | 3,837 | 3,953 | 4,403 | 4,508 | −94,727 |

| Southern India | 237,827 | 245,612 | 241,929 | 323,555 | 336,665 | 348,700 | 359,200 | 359,938 | 360,893 | 123,066 |

All India | 1,141,031 | 1,138,163 | 1,146,583 | 1,188,471 | 1,209,723 | 1,232,150 | 1,255,100 | 1,256,210 | 1,257,610 | 116,579 |

| Permanent workers | Change | |||||||||

| Tea regions | 1996 | 1997 | 1998 | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 1996-2004 |

| Northern India | ||||||||||

| Assam | 498,731 | 496,807 | 503,157 | 477,660 | 477,900 | 481,375 | 487,670 | 512,790 | 519,635 | 20,904 |

| West Bengal | 265,860 | 254,695 | 258,269 | 210,760 | 210,932 | 211,867 | 214,715 | 228,317 | 232,532 | −33,328 |

| Others | 13,218 | 11,982 | 11,877 | — | — | — | 11,753 | 11,991 | 12,255 | −963 |

| Northern India | 777,809 | 763,484 | 773,303 | 700,227 | 700,710 | 865,553 | 714,138 | 753,098 | 764,305 | −13,504 |

| Southern India | ||||||||||

| Tamil Nadu | 118,587 | 1,059 | 131,640 | 143,223 | 144,427 | 145,406 | 149,446 | 166,362 | 172,782 | 54,195 |

| Karnataka | 5,602 | 4,366 | 281 | 1,933 | 1,926 | 1,921 | 1,975 | 2,234 | 2,335 | -3,267 |

| Kerala | 90,684 | 88,575 | 87,530 | 3,440 | 3,464 | 3,485 | 3,591 | 3,980 | 4,123 | −86,561 |

| Southern India | 214,777 | 223,041 | 219,451 | 219,411 | 221,354 | 222,360 | 228,535 | 255,678 | 265,937 | 51,160 |

| All India | 992,586 | 986,520 | 992,754 | 919,638 | 922,064 | 927,213 | 942,673 | 1,008,776 | 1,030,242 | 37,656 |

| Temporary workers | Change | |||||||||

| Tea regions | 1996 | 1997 | 1998 | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 1996-2004 |

| Northern India | ||||||||||

| Assam | 92,237 | 94,229 | 95,668 | 119,283 | 124,631 | 129,688 | 131,993 | 106,532 | 97,883 | 5,646 |

| West Bengal | 27,233 | 28,111 | 28,698 | 40252 | 42,527 | 43,702 | 44,467 | 32,019 | 30,140 | 2,907 |

| Others | 5,925 | 6,732 | 6,985 | — | — | — | 5302 | 4,623 | 4,272 | −1,653 |

| Northern India | 125,395 | 129,072 | 131,351 | 164,689 | 172,348 | 17,897 | 181,762 | 143,174 | 132,412 | 7,017 |

| Southern India | ||||||||||

| Tamil Nadu | 14,116 | 13,278 | 13,543 | 102,156 | 111,363 | 122,259 | 126,277 | 101,989 | 93,245 | 79,129 |

| Karnataka | 283 | 276 | — | 12 | 32 | 31 | 36 | 147 | 129 | −154 |

| Kerala | 8,551 | 9,017 | 8,935 | 240 | 325 | 352 | 362 | 423 | 385 | −8,166 |

| Southern India | 23,050 | 22,571 | 22,478 | 104,144 | 115,311 | 126,340 | 130,665 | 104,260 | 94,956 | 71,906 |

All India | 148,445 | 151,643 | 153,829 | 268,833 | 287,659 | 304,937 | 312,427 | 247,434 | 227,368 | 78,923 |

Source: Compiled from Tea Statistics, Tea Board of India, various years.

Overall engagement of temporary tea workers on plantations in India, however, grew much more strongly, driven by sharp growth in Tamil Nadu and positive increases in Assam and West Bengal, particularly in tea areas in Darrang district in Assam. In West Bengal, growth in the temporary tea workforce was greatest in the Terai and the Dooars regions. Attrition of the permanent workforce and resulting casualisation of plantation labour has been most severe on the Dooars estates; nearly 22,000 permanent worker positions have been lost over the reference period.

Changes in the deployment of male and female tea workers in India between 1995–2004, as depicted in Tables 4 and 5, show opposing trends between tea plantations in north India and south India. The figures in the tables represent the rise or decline in the number of workers in each category. While the aggregate tea workforce grew in Assam and West Bengal for both male and female tea workers, the male and female tea workforce in the southern Indian States of Kerala and Karnataka experienced a very sharp decline. The tea workforce in India has characteristically been categorised into resident and outside workers. As mentioned above, plantation workers who reside within the tea estate with their bonafide dependents are entitled to receive PLA non-wage benefits. Conversely, tea workers who reside outside the estate receive only wages. The category of outside workers comprise both outside permanent workers who are entitled to haziri employment around the year and outside temporary (bigha) workers who are recruited as casual labour for short durations during plucking cycles. The tea workforce also comprises field workers who are engaged for plucking and plantation maintenance and factory workers who perform various processing tasks at the estate factories. Table 5 only shows the figures for resident and outside field workers.

Table 4 Change in the number of tea workers, by sex and region, 1995–2004 in number

| Tea region | Male workers | Female workers | Total workers |

| Northern India | |||

| Assam | 30,897 | 29,491 | 50,120 |

| West Bengal | 3,057 | 5,751 | 4,493 |

| Others | 1,310 | −434 | 335 |

| Northern India | 35,264 | 34,808 | 54,948 |

| Southern India | |||

| Tamil Nadu | 72,452 | 82,854 | 1,55,278 |

| Karnataka | −29,307 | −37,557 | −67,774 |

| Kerala | −48,009 | −47,650 | −96,660 |

| Southern India | −3,27,023 | −2,86,675 | −6,67,894 |

All India | 5,97,835 | 6,20,750 | 12,57,610 |

Source: Computed from Tea Statistics, Tea Board of India, various years.

Table 5 Changes in field workforce, by type of worker and sex, 1995–2004 in number

| States | Resident males | Resident females | Resident field workers | Outside males | Outside females | Outside field workers |

| Northern India | ||||||

| Assam | 12,039 | 41,280 | 47,668 | 5,130 | −14,093 | −12,317 |

| West Bengal | 1,503 | 17,243 | 18,344 | 258 | −12,589 | −16,122 |

| Others | 948 | 333 | 1,034 | 159 | −400 | −530 |

| Northern India | 14,490 | 58,856 | 67,046 | 5,547 | −27,082 | −28,969 |

| Southern India | ||||||

| Tamil Nadu | 24,993 | 35,735 | 60,592 | 46,351 | 46,255 | 92,711 |

| Karnataka | −294 | 714 | 414 | 122 | 39 | 137 |

| Kerala | 1,974 | 14,564 | 15,791 | 1,726 | 126 | 1,977 |

| Southern India | 26,673 | 51,013 | 76,797 | 48,199 | 46,420 | 94,825 |

All India | 41,163 | 1,09,869 | 1,43,843 | 53,742 | 19,338 | 65,856 |

Source: Computed from Tea Statistics, Tea Board of India, various years.

Between 1995 and 2004 there has been a substantial decline in the field workforce engaged from outside for plantations in Assam and West Bengal. The decline has been sufficiently marked for outside female field workers, although the numbers of outside male field workers has grown. Conversely, in the plantations in southern India, where non-wage benefits are generally not paid out, the outside male and female workforce has grown.

The Indian retail tea market has been dominated by Hindustan Lever Limited (HLL) and Tata Tea, both of which had a strong vertically integrated presence in tea blending and in running their own tea plantations. After the commercial crisis in the 1990s, both corporates divested their ownership of tea plantations to concentrate on the retail end of the tea value chain, where profits were secure. While the erstwhile HLL estates were sold en masse to other tea majors such as McLeod Russell, the Tata-owned plantations (formerly Tata-Finlay) were restructured into two new entities comprising the Kanan Devan Hills Plantation Company in south India and the Amalgamated Plantations Private Limited (APPL) in Assam and the Dooars (CULS 2014). Both new entities were created to run the tea plantations on principles of worker-ownership, by which means the risks of running plantation operations could be transferred to plantation workers, while the profits from the retail segment were secured firmly with the blending companies. Two comprehensive studies document the fallout of labour distress among estate workers (CULS 2014 op. cit.; FIAN 2016), along with evidence of widespread gender inequality and discrimination.

Although disaggregated data after 2004 have not been published by the Tea Board, growth of small tea garden (STG) plantations has burgeoned in Assam and the Dooars over the subsequent 14-year period. However, this did not represent the conversion of existing plantation estates into smallholder tea plantations. The area brought under STG plantations has thus been a sizeable addition to the large area under tea cultivation that already existed on the Assam and Dooars tea estates. This was achieved through the conversion of farmlands where agricultural cropping was abandoned for perennial tea cultivation. The incentive to convert revenue lands to tea plantations was provided by high buyback prices for green tea that prevailed for a short time. Subsequently, when green leaf prices drastically fell, the profitability of STG operations saw extreme fluctuations.

This problem principally arose because of the lack of stable pricing for green leaf sales by STG producers to bought leaf factories (BLFs). As smallholder tea plantations are essentially farming operations with no fixity in wage payments, STG growers depended exclusively on BLF tea producers for their earnings. Whenever green tea prices crashed, they resorted to even greater volumes of tea plucking to make up for shortfalls in earnings. This had the effect of magnifying price volatility in the STG sector. Secondly, as green leaf prices were paid after the realisation of market prices by the BLFs, the latter were able to transfer their market risks entirely to STG growers.

Over the last 14 years, a cloak of invisibility has been thrown over working conditions of women workers on STG plantations. Women pluckers, who were field workers and wage earners in their own right on the large estate plantations, were now only able to add an informal helping hand to family labour applications on smallholder plantations. While it appears that the ills of the estate system disappeared from oversight in the STG segment, gender inequality and discrimination became far more embedded. Women on STG plantations once again substituted male family labour by unremunerated women’s work.

In the wake of deepening distress caused by juxtaposing two categories of poor tea workers against one other, competitiveness has weakened in labour markets. Tea corporates are able to cite the low productivity of their workers to further casualise their workforce, reduce wage-costs, and increase the magnitude of plucking tasks assigned to women workers. Since under the prevailing system of productivity-linked wages, overtime wage payouts are only made after completion of daily plucking tasks, worker productivity can be raised without incurring additional labour costs.

The rates of casualisation displayed in the above tables have grave implications. Women workers are marginalised on the Assam and West Bengal tea plantations, where their expanded presence indicates they are increasingly substituting for male work. The growth of casual plantation work opportunities for women comes at the cost of reduction of permanent earning opportunities for other family members. Meanwhile, the growth of smallholder tea operations outside the estate periphery is transforming small peasant holdings into new plantations. STG tea plantations have invisibly captured the labour that farm women and children had previously devoted to food production. This has been accomplished without arbitration by a formal labour market or a formal labour wage. Restructuring of the tea sector in Assam and West Bengal has worked in favour of sustaining the development and growth of Indian tea through innovations in labour reorganisation. However, this has not liquidated the large estates, but has further bolstered their market power.

Importance of Plantation Restructuring

The plantation economy in India, since its inception, has retained its early attributes of low levels of capital, high labour absorption, and labour unfreedom perpetuated through family wage-determination and piece-rated work in Assam and the Dooars. High absorption of women’s labour on tea plantations persists as a means for tying tea labour to plantations and lowering labour costs rather than as a progressive indicator of gender equity in plantation work. Despite multiple legislation to alleviate the exploitation of plantation workers after Independence, labour conditions on tea plantations have not changed fundamentally. Phenomenal growth in the domestic market for tea has not resulted in increased prices and profitability of the Indian tea industry, which still remains a passive player in the global tea value chain where the bulk of profits accrue at the upper end to international tea blenders and the beverage industry. While the large tea estates of Assam and the Dooars have sought to preserve competitiveness by seeking dilution of plantation labour benefits, the burgeoning small tea grower sector in India has been used to play off one section of poor plantation workers against another. In the absence of comprehensive policy initiatives to understand and engage with the changing character of global tea marketing, the long-term prognosis for the Indian tea industry remains poor.

Glossary

bigha worker: literally, casual tea workers engaged for limited periods/tasks on the Assam plantations, also known as faltu workers.

hazira workers: literally, daily-rated permanent tea workers entitled to payment of the haziri wage-rate when daily work is assigned to them.

haziri: literally, the daily wage payable to a permanent tea-worker when s/he shows up for work.

Kangany: overseer-cum-labour contractor.

mini-zamindari: a system of notional subinfeudation whereby the leaseholder of an estate leases out unutilised estate lands to tenant farmers on consideration of cash rental payment.

thika: literally, the minimum daily plantation task to be fulfilled by daily-rated tea workers to earn the task-wage. For women pluckers, the plucking thika is tasked at the given daily wage. Under the system of productivity-linked wages, any surplus of leaves plucked after the completion of the thika task is remunerated at the higher extra-task rate.

References