ARCHIVE

Vol. 10, No. 2

JULY-DECEMBER, 2020

Editorials

Research Articles

Research Notes and Statistics

Review Articles

Agrarian Novels Series

Book Reviews

The Human Cost of Fresh Food:

Romanian Workers and Germany’s Food Supply Chains

*Zalau Museum of History and Art, Romania, valer.simion.cosma@gmail.com.

†Copenhagen Business School, Denmark, cba.ioa@cbs.dk.

‡University of West England, United Kingdom, daniela.gabor@uwe.ac.uk.

Abstract: Fresh food supply chains in Europe’s transnational agribusinesses depend on cheap, non-unionised, and privately managed labour from low-wage eastern European countries. The costs versus benefits of this phenomenon are under-studied. By examining seasonal farm migration from Romania to Germany, we argue that the Covid-19 pandemic is, for farmworkers, a Janus-faced event. On the one hand, it has worsened the precarity of migrant farmworkers. Changes in the German state’s pay legislation that excluded workers from social benefits, and the reluctance of the German state to enforce labour legislation to the full in the early stages of the pandemic sharpened what we have termed the structural disempowerment of migrant farmworkers. Romanian seasonal workers have had little choice but to implicitly subsidise the costs of German farm products. At the same time, the health crisis has made their work visible and led to processes that challenge the perception of migrant workers as passive agents. In this regard we refer specifically to (i) the supportive media coverage in Romania, Germany, and beyond and (ii) the assertion of union-affiliated farm and abattoir labour activism in Germany. These planted seeds of contestation, and collective action against abuses sprang up in several farms. Combined with a flare-up of Covid-19 in German abattoirs in the summer of 2020, these campaigns for visibility and improved working conditions led the German government to alter legislation so as to better protect seasonal labour in the fresh vegetable and meat sectors. Going forward, the tension between these two opposing sociopolitical drivers may shape the governance of seasonal labour in Europe.

Keywords: Romania, Germany, migrant agricultural workers, seasonal agricultural work, food supply chains, Covid-19, labour unions

Introduction

Europe’s food supply chains would fall apart without workers from eastern Europe. This reality has once again, and in a dramatic way, been highlighted by the Covid-19 pandemic. At least a million and a half farmworkers from “the East” are needed for these perishable-good supply chains. It was Brexit Britain that first announced that their country’s crops would rot in the fields if close to 100,000 farmworkers from eastern Europe – typically the object of Brexiteers’ xenophobic scorn – were not immediately airlifted to the United Kingdom.

Subsequently, the Netherlands, Germany, and Belgium organised air bridges to transport agricultural workers from Romania and Hungary through the months of April and May, when most of eastern Europe was in quarantine. While the Romanian army and police patrolled communities, handing out fines for the smallest breaches of lockdown, the Romanian government also effectively created a sector of exception within that state of quarantine by allowing tens of thousands of workers to return to the orbit of precarious seasonal migration to German (and other western European) farms. In the early stages of the pandemic, the German government expressed concerns regarding the supply of fresh food (Neef 2020, p. 642); these measures of the Romanian government addressed those concerns.1

Western European farms benefit from massive European Union (EU) and national subsidies, which crowd out agricultural exports from the global South (Bureau and Swinnen 2018). Yet the pay and working conditions in parts of Europe’s food supply chains that are not yet automated (such as those of fresh produce or meat) remain precarious. International supermarkets pit producers against each other and rely on wage suppression to retain the relatively small profit margins of these sectors.2 While the Eastern European workers, in theory, enjoy the legal protection awarded to formal labour by EU law, the Covid-19 pandemic has exposed, and in some cases sharpened, working conditions that are often exploitative. This was true not just of countries with large informal sectors, weak labour unions, and dual labour markets, such as Greece, Spain, or Italy (Ban 2012; Ban 2016; Durazzi, Fleckenstein, and Lee 2018), but also of countries like Germany, where informal-sector work in the economy is low and, despite the recent erosion, labour relations are tightly regulated by labour unions (Mummert and Schneider 2002).

Eastern Europe’s incorporation into the manufacturing chains of western Europe turned these countries into exporters of increasingly complex products, particularly in the automotive sector, with record low levels of unemployment as the main result (Ban 2019; Adăscălitei and Guga 2020). Furthermore, eastern Europe experienced significant increases in real wages, powered in part by an active industrial policy (Markiewicz 2019) and income policy (Ban and Adăscălitei 2020). In Romania, the average net wage increased by nearly 400 per cent between 2005 and 2020,3 and the net minimum wage rose by 300 per cent in a shorter period (2008–20).4 East-central Europe may be a periphery of European capital, but it has done much better than the countries of the region that did not become a part of the EU, with Ukraine, the more impoverished western Balkans, and Moldova serving as cautionary development pathways. Given this, why do such large contingents of eastern European workers continue to expose themselves to harsh, precarious labour and pandemic-related health risks?

This article, which is based on fieldwork, focuses on Romania, by far the largest source of intra-European migration in general, and seasonal farm labour in particular.5 The focus is on seasonal Romanian labour in Germany’s agriculture, a section of Europe’s labour market whose exploitative practices, high levels of informal work, and abusive working conditions have been relatively ignored by academic research published before the Covid-19 pandemic (most of the literature on this topic deals with southern Europe or the USA). Moreover, the studies published after the pandemic began are descriptive and based on desk research (García-Colón 2020; Neef 2020).

Post-Communist Enclosures and Push Factors of Migration

The large share of the rural population in the total population of Romania is the result of late urbanisation, a reliance on rural–urban commuting, and the comparative advantage of commuters having higher net incomes as a result of saving on housing and food costs. During the extensive de-industrialisation triggered by the market reforms of the 1990s (Gabor 2010), Romania even recorded some urban–rural migration as a survival option among sacked industrial workers. The shock therapy of 1997 raised the phenomenon of urban–rural migration to unprecedented levels (Sandu 1999, pp. 160–70; Sandu 2010, p. 52; Kideckel 2010, p. 150; Petrovici 2013, p. 46; Mateoc-Sîrb et al. 2014, p. 216; Ban 2014).

Nevertheless, beyond survival, a healthier natural environment, and tighter communities, rural life has little to offer in economic terms. After collective farming came to an end in 1989, the transformations of the 1990s dealt hard blows to prospects of living off the land in Romania. The dismantling of large, state-owned agribusinesses and the restitution of land to former owners and their heirs did not bring about a mass of profitable medium-scale farms as the advocates of reforms had promised (Petrovici 2013; Troc 2016). Instead, livestock was halved, irrigation systems fell apart, and large expanses of land were left fallow, with millions of owners deprived of modern means to work the land or institutionalised markets to sell the output (Fraser and Stringer 2009). In a short time, Romania turned from a net food exporter to a net food importer, and as the restraints on re-privatisation of land were lifted in 2005, most of the land was purchased at bargain prices by private agribusinesses and investment funds adept at land-grabbing (Popovici, Bălteanu, and Kucsicsa 2016, p. 337).

Most importantly, the combined outcome of highly unequal class relations at the time of nationalisation (1950s) and contemporary market-based agricultural reforms was a highly polarised land structure, with 52 per cent of arable land occupied by farms of over 100 hectares, 4.5 per cent of land owned by middle farmers (10–50 hectares), and the rest being highly fragmented small farms of less than 10 hectares each. Most of this land is used to cultivate cereal, cattle feed, and monocropped sunflower. In contrast, the potentially profitable medium-sized farms provide income to a smaller share of the rural population in 2020 than they did during the neo-feudal early 1900s. The rural middle class (whose holdings are between 10 and 50 hectares) constituted 3.7 per cent of the rural population in the early twentieth century and owned 8.9 per cent of arable land. The share of this section in the rural population today, 4.7 per cent, is roughly the same as it was a hundred years ago (Mihăilescu 2018, pp. 26–27).

To this day, the prospects for the rural masses breaking out of subsistence farming and the associated low incomes are limited. While permanent farmers’ markets proved to be resilient in urban Romania, local farmers have been edged out of these markets by semi-formal food sellers who are agents of local agribusinesses or importers. The success of legislative attempts in 2017–18 to force supermarkets to purchase a part of the food from local producers was short-lived. The income from farming, even in the best of cases (rural producers of organic or semi-processed foods for sophisticated consumers), hovers slightly above the gross earnings from wage work at the minimum wage.6

The long-term consequences of neoliberal restructuring unmediated by social bargaining (Ban 2020a) and combined with a weak state prevent small farms from generating sustainable and decent incomes. There is thus a strong and rational impetus for seasonal migratory work, even at the peak of a pandemic. Migration is further enhanced by the thin safety nets that exist in Romania, a reflection of it being a country with fragile finances (Ban and Rusu 2020).7

Most informants describe the work on German farms as extremely demanding. This account as told to Alexandra Voivozeanu by one of our respondents is typical:

We were paid according to the boxes of vegetables harvested. We worked from dawn until 7 p.m. Sometimes we worked at night, with tractor headlights illuminating the fields. It was tough. No toil, no gain. They paid 60 cents for each box of carrots and 1 euro and 80 cents for a box of onions. No way could you earn anything if you dragged your feet. You had to push on and on. They never gave us any paid holidays. We worked Sundays. We worked on Easter. The Germans observed the holidays, but they sent us into the fields. We were probably between 300 and 400 people from Romania alone, most of us from the villages of Maramures and the Salauta Valley.

The overall income differentials between Romania and Germany explain much of the willingness of Romanian workers to engage in this kind of seasonal activity, including taking health risks during a pandemic. Taking an entire year, the gap between monthly net income from seasonal work in Germany for periods averaging six months (€6000) and the net minimum wage in Romania for two months (€3300) is hardly dramatic.8 There is also the physical stress from the extremely long 15-hour work days of a migrant worker. The decision to migrate makes more sense when one accounts for the fact that transnational seasonal work is often combined with flexible work arrangements at home. Some of the seasonal workers have full-time contracts in Romania and negotiate a two-month leave of absence (we even found a policeman among them), with employers accepting this arrangement due to a tight labour market and worker leverage. Thus, the income from seasonal work is a net addition to incomes earned at home. So, it is not merely the wage differential between Germany and Romania but the overall income differential that explains the willingness of seasonal migrants to cope with the additional toil. These findings reinforce Ágota Ábrán’s (2016, 2018) insight that transnational capital in areas as diverse as medicinal plant picking and fresh food appropriates the outcome of bespoke yet low-paid skills for maximising productivity.

Drivers of Seasonal Farm Work: A Review of the Literature

There is a rich literature that explains why the demand for low-wage, highly insecure labour in European food harvesting and processing shifted from domestic/local to global/migrant labour. Despite labour market deregulation and welfare trimming since the 1990s, the flexible pool of farmworkers in high-income EU member-states shrank as villages were depopulated (Kasimis, Papadopoulos, and Pappas 2010), rural women joined non-farm labour markets (Rye 2014; Kasimis, Papadopoulos, and Pappas 2010), and low-skilled rural youth took up better-paid jobs in the growing service sector, whose expansion in the countryside was in part ushered by the same deregulatory processes that facilitated the expendability of these workers (García-Colón 2020).

The post-2008 austerity-based macroeconomic regime failed to reverse this structural trend, despite a drastic increase in the numbers of employed and underemployed persons (Helgadóttir 2016; Perez and Matsaganis 2018). In Germany, farm work pays a minimum wage (€1555 per month), which is almost four times the level of unemployment benefits (€432 per person per month). Nevertheless, the fact that housing and child benefits are not paid in cash, as well as the demanding physical strain involved and, often, the skills necessary for work in greenhouses or abattoirs (Voivozeanu 2019) keep the local precariat away from the labour-starved parts of the food chain. The result has been employer preference for international labour (Kasimis 2008; Rye and Scott 2018), particularly the “just-in-time” migrant workforce demanded by vertically integrated food chains and agribusinesses (Rye and Scott 2018).

Critical factors powering the dependence on Romanian labourers are their higher productivity, willingness to work longer hours, willingness to cope with sub-par working and living conditions, and at the same time being easy to replace (García-Colón 2020). An important source of consensus in the literature that suggests that these features of the workforce are due to structural disempowerment (acceptance of informal work arrangements, lack of language competence, and very limited integration into labour unions are typical of rural populations) and a dual frame of reference (low wages and poor working conditions in the home country makes seasonal labour in the richer country relatively tolerable, and even appealing) (Rye and Andrzejewska 2010; Rye and Scott 2018; García-Colón 2020). Consequently, “employers see the results of this through the presence of migrant workers who appear motivated, reliable, and attractive to employ, especially relative to would-be domestic workers” (Rye and Scott 2018).

This article probes the analytical value of the structural disempowerment and dual frame of reference theses in the case of seasonal migration of Romanian workers to Germany, a country where 700,000 Romanians form a veritable army of essential workers in areas as diverse as healthcare and agriculture.9

Methodology and Data

Our methodology is that of a qualitative case study. We draw on 25 in-depth interviews with seasonal workers in several high-migration sites in Romania (Bistrita-Nasaud, Maramures, and Salaj). The interviews were carried out by one of the authors in May and August, 2020. Additionally, the same author carried out personal observation of transport activities in these areas in Romania. All the authors undertook a close reading of Romanian, German, and British media reports; institutional social media posts; statistical registries; and secondary literature. In addition to interviewing the seasonal workers themselves, we also exchanged e-mails and had telephone conversations with German labour organisers working with seasonal workers and with members of a Romanian producer cooperative from northern Romania (Produs in Bistrita-Nasaud).

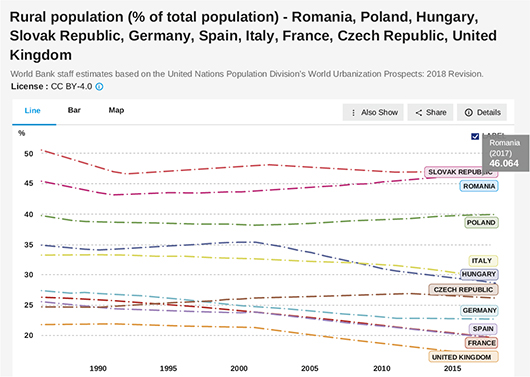

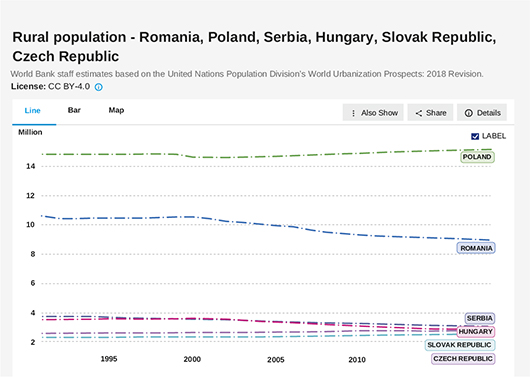

Romania is an interesting case because it has Europe’s largest pool of rural labour, with 46 per cent of the population living in rural areas in 2017 (Figure 1) and with agricultural employment accounting for 22 per cent of the active labour force in 2020 (though down from 31 per cent in 2010). Indeed, in eastern Europe, Romania, Slovakia, and Poland (in this order) have the largest proportions of rural population in total population. However, in absolute numbers, Poland and Romania together have a total rural population of about 25 million people (Figure 2), a number that dwarfs newer EU member-states, and between the two countries, the share of rural to total population is higher in Romania. We calculated that, in 2017, about four million Romanians were experienced farmers. Of these, a large number were from mountainous areas with scarce cultivable land and having decades of experience of internal migration for farm or forestry work (Petrovici 2013, pp. 43–44), going back to the period of state socialism and the early transition years (Troc 2016, p. 59). It was from these regions that we selected our informants: Oas, Maramures, and Tara Năsăudului.

Figure 1. Rural population as a proportion of total population, Romania, Poland, Hungary, Slovak Republic, Germany, Spain, Italy, France, Czech Republic, and United Kingdom, 1990–2015

Source: UN (2018), as processed by World Bank data mapper.

Figure 2. Rural population, Romania, Poland, Serbia, Hungary, Slovak Republic, and Czech Republic, 2018, in million

Source: UN (2018), as processed by World Bank data mapper.

All three authors were born and raised in these regions, and this enabled them to reduce the social distance with the interviewed workers. In terms of selection criteria, these fieldwork sites are particularly interesting also because their history of familiarity with the German-speaking world (the region was a part of the Austro-Hungarian empire until 1918) gave their inhabitants a rich horizon of expectations about working for and interacting with German speakers (Cosma 2008, 2009, 2011).

Structural Disempowerment

Our interviews and analysis of relevant media reports suggest that Romanian seasonal workers continue to migrate for seasonal work even during a pandemic for different reasons: the possibility of higher wages, the paucity of wage work within commutable distances (rents for a family of four on minimum wage can take up more than half the wage income), the aspiration to fund expenses of children’s higher education in expensive college towns, and the need to build homes that ensure privacy and have bathrooms.10 However, structural disempowerment was sharpened by the pandemic crisis, as the German state accommodated the structural pressures to lower labour costs in the farming sector.

Before the pandemic, coalitions of trade unions, farmers’ associations, NGOs, and church groups had emerged to address the informal working conditions of eastern European seasonal workers. With funding from the German state and the DGB (Deutscher Gewerkschaftsbund, the German Trade Union Confederation) union, coalitions such as Faire Mobilität (Fair Mobility) sought to enforce fair wages and working conditions in line with German law. The pandemic complicated these, however, allowing German farmers to exploit the weakening of the German state’s ability to enforce labour regulations (Baccaro 2015; Baccaro and Howell 2017) and its willingness to relax these amidst the crisis to allow farmers to address the chronic labour shortages.11

While some of the workers received contracts before leaving Romania, most of them signed contracts only upon arrival. The terms were opaque, and farmers tended to not provide the workers with copies of the contracts.12 Perhaps more importantly, employers often disregarded the formal terms, particularly those concerning hourly pay, resorting instead to informal agreements and quotas. They could do so by exploiting the long-term hollowing out of the bureaucratic infrastructure that enforces labour rules. This situation was not something new, it was only made visible due to the pandemic. Faire Mobilität reported that labour standards such as payment of the German minimum wage or pandemic-time housing standards (one person per room, except for families) in farming could not be adequately enforced because of the understaffing of labour inspectorates (less than 10 per cent of farms were inspected in 2019).13 Similarly, the German government admitted that it lacked the staff to enforce work and health safety rules in slaughterhouses, a problem compounded by the existence of myriad subcontracting arrangements engaging in complex blame games that are hard to adjudicate.14 Structural disempowerment also manifested itself in the lack of legal support for workers who had to face employers for breach of contracts or other measures with legal consequences, which were used to intimidate poorly educated non-German-speaking farmworkers.15

There were, however, new developments brought by the pandemic. According to German media reports, the frequency of inspections checking on health standards fell further in the first months of the pandemic,16 with the German Labour Ministry taking six months to step up controls, and that too only in response to a flare-up of infections during the summer of 2020 and under pressure from the media and labour union activists working amongst farmworkers.17 There have also been reports of quarantine conditions being observed loosely, with cases of infected workers being made to live in close quarters in containers with bunk beds and even compelled to work in the field while sick.18 Furthermore, the German state extended the employer exemption for social security contributions from 70 to 115 days, which left seasonal farmworkers even more vulnerable to the health arrangements made by each employer. In effect, this meant that they were tied to the farms where they started work upon arrival. Surprisingly, the German state did not seek to enforce the terms under which pandemic-time work could be organised. Although a concept paper of the German Agriculture and Interior Ministries clearly stipulated that transportation costs had to be assumed by the farms, our informants and Faire Mobilität pointed out that the opposite was often the case in practice, with bus fares subtracted from the workers’ pay. The German state also made little effort to set up formal coordination mechanisms with the Romanian state. The Romanian government made symbolic gestures such as token ministerial farm visits. Even these were undertaken only in response to a great deal of international media coverage, which led to media coverage in Romania.19 This included even conservative and private TV stations otherwise insensitive to labour issues, adding to the chorus in the home country.20 All this, however, had no impact on the actual working conditions until a second outbreak of the pandemic, which hit German abattoirs in the summer of 2020 and led to a change in German law banning labour subcontractors in large abattoirs and farms. A similar passivity was true of the Romanian labour confederations, which remained unresponsive to the initiative of their German peers to unionise seasonal workers so that they could be better protected via transnational labour union deals.

Organisations like Faire Mobilität are not state agents and are too few in number to deal with the flow of hundreds of thousands of workers. In other words, while one can see some of the institutional elements of a state–labour union partnership that one would expect from Germany’s social solidarity traditions, when it comes to the systematic enforcement of labour standards for seasonal workers, the German state was not the strong state one would have expected, at least for the duration of the lockdown.

Structural disempowerment is magnified by Romanian workers’ reluctance to join labour unions despite information campaigns organised by the latter.21 This is not surprising. First, rural workers are not used to labour unions. The labour union movement in Romania is a shadow of what it was during the first transition decade, with the 2011 neoliberal reforms leading to a major collapse in membership and institutional leverage (Adăscălitei and Muntean 2019; Adăscălitei and Guga 2020); but even in its heyday in the 1990s and early 2000s, it never penetrated in the countryside, where independent farms dominate and the share of landless population is relatively small. No social bloc with political representation for farmers exists in Romania, so the socio-economic problems of the countryside are not articulated in the political agenda in organised ways as historically observed elsewhere (Ban 2020b). Though both social democratic and socialist unions have been active on German farms and have deployed Romanian and Polish-speaking organisers (with one of the unions managing to coordinate a strike), their reach has been limited due to the fact that workers often mistook labour activists for agents of the German state, leading to mistrust.22 Secondly, even in the neo-corporatist systems of north-western Europe,23 the idea of labour union representation for seasonal workers is new and the resources dedicated to this line of work remain relatively low.24

Nevertheless, a combination of renewed flare-ups of the pandemic during the summer of 2020, media attention, and renewed labour union efforts led the Bundestag (the German federal parliament) to plug a loophole that enabled German meatpacking firms and farms to hire subcontractors accused of abusive labour practices (undercounted work hours, charges for equipment, unhygienic and cramped accommodation). Although these changes have been on the labour agenda for decades, the abattoir lobby in particular had prevailed before the pandemic. The changes, which make farms and abattoirs directly responsible for housing standards and equipment for electronic recording of hours, will nevertheless not come into effect until January 2021.25

Dual Frame of Reference

Romanian seasonal workers in German agriculture are keen to push their labour to maximum productivity levels. They are paid by quotas based on verbal agreements, have to navigate precarious working conditions, and have little access to health security when they get injured on the job. Their work and living conditions at home are often comparable, and for some, conditions are worse in Germany than at home. Many of them come from communities that had engaged in domestic seasonal work away from home for many decades and under even more demanding terms.

In the work culture of internal migration from Romania’s mountainous areas to the plains during the periods of socialism and early transition, “performance pay” (piece-rated work, paid by quantity harvested), based on oral agreements, was standard. Moreover, payment was mostly in kind, with workers transporting corn back to their villages by train to feed pigs and cattle, which they then sold.26 A respondent from the village of Telciu said that the housing was basic and overcrowded (58 persons to a room), sanitation was non-existent, and working hours lasted from dawn to sunset. Many of the seasonal workers are over 50 years of age and have not known any other kind of working conditions. Compared to this, living in gender-separated containers, six to a room and with some access to bathrooms (however squalid), may seem like an improvement. Other researchers have confirmed the difficult working conditions of domestic seasonal work during the years of socialism and the 1990s (Troc 2016, pp. 59–60).

By law, and in contrast to European countries such as Spain, seasonal workers in Germany do not receive benefits in addition to net wages. This passes the burden of social welfare to the Romanian state and the sending communities – another aspect of East–West asymmetries. Our fieldwork confirmed that highly vulnerable rural populations, and particularly rural women with no history of formal employment, were culturally accustomed to the idea of not having access to pensions or proper health insurance (workers carried medicine with them and seemed to take pain-relief medicine to cope with heavy labour), having lived for decades in an informal subsistence farming regime where free healthcare ceased to be a reality after the end of socialism. But while old-age care used to be provided by traditions of intergenerational solidarity in the family, the erosion of these traditions makes seasonal migrants even more socially vulnerable.

Romania has a low unemployment rate, and the main complaint of both the manufacturing and service sectors before the pandemic was shortage of labour (Ban 2019). This led the government to issue 40,000 work permits for migrant workers from Asia in 2019. One may wonder why the shortage of labour in Romania could not be addressed by the population surplus in the countryside. Our interviews and consultation of official wage statistics suggest that, for most of this population, the choice is between an industrial job in urban areas for a net wage of 300–400 euros a month (plus pension, health insurance, and unemployment benefits) and seasonal migration for six months a year that leaves one with at least twice that amount on a monthly basis but without benefits. The latter option entails much higher work intensity (12-hour days with no weekends off are typical) for two seasons of nearly three months each. If incomes from migration were taxed, the net income from seasonal migration would shrink to hover slightly above a typical industrial job in Romanian towns, making it less attractive. Indeed, if they were to provide benefits and keep the net wages attractive, current pay levels for farmworkers in Germany effectively would have to be nearly twice as high as at present.

In this way, since the German state assumes no responsibility for old age support and healthcare, these two critical items will most likely be passed on to the budgets of the families of these workers and the meagre social security budget of the Romanian state. Thus, German supply of fresh food at current prices depends on the German state shrinking the social wage (mean income after allowing for redistribution through taxes and transfers in money and real terms) to workers such as Romanian farm labourers.

Interviews with the workers suggest that, in many cases, German farmers did not provide housing and transportation conditions that could enable minimum social distancing, whereas the provision of sanitation facilities was minimal.27 Indeed, informants said they lived in the same tenements as they did before the Covid-19 pandemic. Beyond wearing masks and being banned from leaving the farm premises, no other measures seem to have been taken on a systematic basis. These loose health standards had consequences: one asparagus picker died of Covid-19 without receiving medical care, and in a German slaughterhouse, 500 Romanian workers became infected because of cramped housing conditions. Romanian hospitals, which had 1,500 respirators for a resident population of 19 million, would be left to take care of the migrant workers’ parents and grandparents if the latter were exposed to the virus upon workers’ return from the job.

Beyond economic motivations, there are transformational cultural factors at work as well. In the Romanian countryside, the transition to adulthood tends to be intermediated by early participation in the labour market (Horváth 2008, p. 782). Indeed, participation of children and adolescents in the toils of the family farm or informal farm employment with other families is the norm, albeit decreasingly so. It is on the back of this cultural structure that the transformations ushered by transnational seasonal work manifest themselves.

Thus, our personal observations and interviews confirm that there is a culture of migration emerging amongst rural youth in which the acquisition of status in the community hinges on the acquisition of real estate, consumer goods, and used but prestigious brand automobile purchases. Such purchases cannot be made in the short term by transitioning to adulthood via education or minimum-wage jobs in factories. Our interviews with the school inspectorate in Bistrita (county capital of the Bistrita Nasaud region) revealed that, although plumbers, welders, builders, chefs, and bakers formally trained for free in the county’s schools could draw much higher wages and enjoy superior working conditions in Germany than seasonal farmworkers, the prospect of yielding to the cultural pressure to acquire such status markers is far stronger than completing formal education in vocational schools. In the long term, this means that an entire generation of rural youth will have their working lives bedevilled by the vagaries and inequities of seasonal work in agriculture and will not have old-age and health insurance.

Though our informants agreed that long hours are standard and accepted as such for the sake of high levels of pay at the end of the season, there was disagreement on working conditions, with some of them reporting satisfactory conditions on farms, whereas others complained about unsanitary, overcrowded container housing, lack of heating, and inadequate food.28

Before the pandemic, access to health services was often irregular and arranged on an informal basis. Contestation and organised struggle to demand fair treatment was often made difficult by concerns about upholding the networks of solidarity amongst seasonal workers:

I worked for several years (2015, 2016, and 2017) on a farm in Germany, where I was making around €2200 a month – money in hand after food and accommodation. But they worked us like slaves. I would work between 12 and 15 hours a day, waking up at 4 a.m., in the field until 9 or 10 p.m., and then loading the trucks till 12 midnight. There were nights where I got three to four hours of sleep. And when I had to go to the hospital, it had to be on someone else’s health insurance, even if they had charged me for one. I threatened that I would call the Romanian Embassy and the German labour inspectors so they could see how we were mistreated. The owners got a bit scared, but I didn’t want to call because there were many people from my home town working on the farm and I was worried about endangering them. The owners finally decided to pay for the days in hospital, but there, if you don’t work, you don’t earn.

The Covid-19 pandemic, however, made organised responses possible and more visible via social media. It made precarious working conditions worse, since choosing another employer was, at least in the first months of the pandemic, almost impossible if an employer broke the terms of the agreement.29 During the summer of 2020, evidence emerged of a farm resorting to violence and neglecting quarantined workers to such a point that they had to be fed by the Red Cross.30 Denied the possibility of moving between farms, some seasonal workers turned to collective organising. Faire Mobilität noted cases where workers were paid less than agreed upon, which sometimes led to conflict, mass layoffs, and protest.31

At the same time, our August 2020 interviews and our review of Romanian media investigations revealed, for the first time, that there was deep disappointment with working conditions in Germany and the very idea of labour migration there. Most importantly, however, the institutional context of the German labour market proved to be richer in terms of opportunities for solidarity that qualify for inclusion in the conventional scope of the dual frame of reference thesis. Faire Mobilität has Romanian speakers, and it set up mobile information centres, ran information sessions, and used the local media to name and shame with respect to abuses in working conditions.

By June 2020, the critical German and international media coverage of Covid-19 in German slaughterhouses, combined with strikes and pressures enforced by labour activists regarding work conditions yielded some results, with the German government deciding to limit the presence of intermediaries in meatpacking.32 When a farm in the Bornheim area that was being shut down offered to pay only 360 euros a month (the minimum wage in Romania) and offered stale food, its workers, assisted by a socialist German labour union, organised a strike that enabled them to extract a fairer deal.33 Faire Mobilität also reported to us that in some labour conflicts, workers joined the unions that helped them deal with the dispute. To us, these are forms of class solidarity organised by formal institutions of the German society that belong to the dual frame of reference; given the absence of a Romanian institutional counterpart, they do not yet qualify as a form of transnational solidarity of the institutional kind.

All these offshoots of class solidarity may or may not be a game changer moving towards institutional forms of transnational solidarity involving Romanian and German unions, and future research could follow up to what extent the labour activism of these exceptional times proved to be a systemic challenge to the dual frame of reference. At any rate, our research suggests that in national institutional contexts such as Germany, where labour unions still play an important role and labour legislation has not been thoroughly liberalised, the dual frame of reference concept should not be read as precluding the possibilities for transnational collective action.

Conclusions

In her research on Euroscepticism, Dutch scholar Catherine de Vries argues that for all their differences, the Eurosceptical parties of north-western Europe share two main agenda points: they want less intra-EU migration and lower monetary contributions. Yet the Covid-19 pandemic highlighted the reality that seasonal farmworkers, nurses, doctors, and home caregivers are essential to Europe’s food chains and care sectors.

Going further, this article shows that the security and competitiveness of food supply chains in Germany, the engine of the European economy, do indeed run on structural disempowerment and dual frames of reference of eastern European workers, such as those coming from Romania.

Emerging collective action in Germany and the assertion of labour union activity on farms and in abattoirs induced pro-worker legislative action by the German state and introduced important qualifications to these approaches to our understanding of migrant labour. Moreover, the article uncovers cultural aspects of the dual frame of reference that have not been previously explored.

Both the German state and labour unions have viable institutional infrastructures in place to uphold labour standards. Nevertheless, even if one assumes that the farm and meat lobbies do not always get their way in the legislative arena, existing institutional structures may be far from adequate to deal with widespread informal labour and even criminal practices in this sector (the sector itself often depends on the existence of multiple exceptions to the law).34 Indeed, during the first months of the pandemic, the German state appeared less mighty institutionally and more influenced by Big Food lobby power than conventionally understood.

The East–West asymmetries highlighted in the analysis, the low-wage growth model that prevails in Romania, and the general, though uneven, exclusion of the countryside from the benefits of this country’s integration into the EU underpin the extensive social vulnerability faced by hundreds of thousands of rural Romanians who consider seasonal work as a way of life.

Notes

1 Craciun (2020), Neef (2020), Yapici (2020), García-Colón (2020), Costi and Gabor (2020), and Ban (2020b).

2 In contrast, cereal farms have double-digit margins; see European Commission (2019). For a ranking of profit margins by agricultural activities in a north-western European setting, see Van Galen and Hoste (2016).

3 See INS (2020).

4 See Anghelută (2018).

5 At 3.181 per 1,000 population, Romania’s migration rate in 2020 is one of the highest in the world, on par with the Dominican Republic. According to the International Organisation for Migration, Romania is one amongst the countries in Europe with the largest population losses due to migration (alongside Bulgaria, Croatia, Latvia, and Lithuania). In terms of sheer numbers of emigrants, Romania ranks fourth after Russia, Ukraine, and Poland with 3.5 million migrants (IOM 2019).

7 The lack of tax capacity accompanied by high fiscal deficits is termed a “weak fiscal state” by Ban and Rusu (2020).

8 See Eurostat (2020) for Romanian labour statistics.

9 See Jacobs (2020).

10 One can see the results over time. If, in 2005, 85 per cent of rural homes had no indoor plumbing, in 2018, the share fell to 50.1 per cent (Voicu 2006, p. 15; INS 2018). The size and quality of housing in the villages with large migrant labour improved dramatically, with more than one-fourth of the housing stock rebuilt anew. Most villages now have a small service sector and car ownership has boomed. In some areas, status competition took the shape of building large luxury homes and doing away with centuries-old vernacular architecture (Troc 2016, pp. 59–60). Only the share of rural youth in university has not increased, which is hardly a secondary issue.

11 Authors’ correspondence with Faire Mobilität; see also German press reportage on this issue (Pitu and Schwartz 2020).

14 See Peine (2020).

15 Cosma (2020).

16 Sandt (2020).

17 See Spotmedia (2020).

18 For video, see Digi24 (2020b).

19 For video, see Pitu (2020), Tenter (2020), Nahoi (2020), Digi24 (2020a), and Stoica (2019).

20 See Digi24 (2020b) and Forbes (2020).

21 Post by Marius Hanganu, labour activist at Faire Mobilität. See also Hessenschau (2020).

25 See Solomon (2020).

28 Kühnel (2020).

29 Research conducted by Romanian media outlets and our own fieldwork revealed reports of workers not receiving medical care or having their IDs taken away for the duration of the season.

30 Cosma (2020).

32 Palzer (2020).

34 In September 2020, the German state uncovered a network of labour intermediaries issuing fake papers to citizens of Belarus, Ukraine, Kosovo, and Georgia, placing them in abattoirs and effectively stealing large chunks of their wages under the threat of turning them out. See Hecking and Klawitter (2020).

References

| Ábrán, Ágota (2016), “‘I Was Told to Come Here in the Forest to Heal’: Healing Practices Through the Land in Transylvania,” Transylvanian Review, vol. 25, no. 1, pp. 91–106. | |

| Ábrán, Ágota (2018), “Unwrapping the Spontaneous Flora: On the Appropriation of Weed Labour,” Studia Universitatis Babes-Bolyai Sociologia, vol. 63, no. 1, pp. 55–72. | |

| Adăscălitei, Dragos, and Guga, Stefan (2020), “Tensions in the Periphery: Dependence and the Trajectory of a Low-Cost Productive Model in the Central and Eastern European Automotive Industry,” European Urban and Regional Studies, vol. 27, no. 1, pp. 18–34. | |

| Adăscălitei, Dragos, and Muntean, Aurelian (2019), “Trade Union Strategies in the Age of Austerity: The Romanian Public Sector in Comparative Perspective,” European Journal of Industrial Relations, vol. 25, no. 2, pp. 113–28. | |

| Andrzejewska, Joanna, and Rye, Johan Fredrik (2012), “Lost in Transnational Space? Migrant Farm Workers in Rural Districts,” Mobilities, vol. 7, no. 2, pp. 247–68, March 12. | |

| Anghelută, Bogdan (2018), “Evolution of Minimum Wage in the Economy (2008-2019),” Business Magazin, Oct 29, available at https://www.businessmagazin.ro/actualitate/evolutia-salariului-minim-pe-economie-2008-2019-17571795, viewed on October 10, 2020. | |

| Baccaro, Lucio (2015), “Weakening Institutions, Hardening Growth Model: The Liberalisation of the German Political Economy,” Scholar in Residence Lectures 2015–16, Max Planck Institute for the Study of Societies, Köln. | |

| Baccaro, Lucio, and Howell, Chris (2017), Trajectories of Neoliberal Transformation: European Industrial Relations Since the 1970s, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. | |

| Ban, Cornel (2012), “Economic Transnationalism and its Ambiguities: The Case of Romanian Migration to Italy,’ International Migration, vol. 50, no. 6, pp. 129–49. | |

| Ban, Cornel (2014), Dependenţăşi dezvoltare: economia politică a capitalismului românesc. Tact, Cluj-Napoca. | |

| Ban, Cornel (2016), Ruling Ideas: How Global Neoliberalism Goes Local, Oxford University Press, New York. | |

| Ban, Cornel (2019), “Dependent Development at a Crossroads? Romanian Capitalism and Its Contradictions,” West European Politics, vol. 42, no. 5, pp. 1041–68. | |

| Ban, Cornel (2020a), “Scandinavian Social-Democracy and the Economics of Reformism (1890–1940),” Revista Transilvania, no. 5, May 1. | |

| Ban, Cornel (2020b), “Trods Lukkede Grænser Flyves Landarbejdere til Europa” [Despite Closed Borders, Farmworkers are Flown to Western Europe], Politiken, May 2. | |

| Ban, Cornel, and Adăscălitei, Dragos (2020), “The FDI-Led Growth Regimes of the East-Central and the South-East European Periphery,” CBDS Working Paper, no. 2020/2, Copenhagen Business School, Frederiksberg. | |

| Ban, Cornel, and Rusu, Alexandra (2020), “Romania’s Weak Fiscal State: What Explains It and What Can (Still) Be Done About It,” Ebert Stiftung Romania, Bucharest, pp. 1–50. | |

| Bureau, Jean-Christophe, and Swinnen, Johan (2018), “EU Policies and Global Food Security,” Global Food Security, no. 16, pp. 106–15. | |

| Cosma, Valer Simion (2008), “Imaginea „neamţului" în sensibilitatea intelectualităţii năsăudene,” Caiete de Antropologie Istorică, no. 12–13, pp. 187–207. | |

| Cosma, Valer Simion (2009), “Clerul ardeleanşi aspiraţiile naţionalismului modern din veacul al XIX-lea,” Caiete de Antropologie Istorică, no. 14, pp. 181–200. | |

| Cosma, Valer Simion (2011), “Clerul român din Transilvania şi proiectul identitar national,” Caiete de Antropologie Istorică, no. 18, pp. 42–50. | |

| Cosma, Valer Simion (2020), “The Nightmare of some Romanian Workers on a Farm in Germany: Beaten and Without All the Money Paid,” Libertatea, Aug 19, available at https://www.libertatea.ro/stiri/cosmarul-muncitori-romani-ferma-focar-germania-batuti-fara-bani-platiti-3096113?fbclid=IwAR0bA2QqKdEdl2taT2r5N8-h10BLKu8rR51k9dDSDLAGR_U3U2BB9Se7VJ8, viewed on October 22, 2020. | |

| Costi, Rogozanu, and Gabor, Daniela (2020), “Are West European Food Supplies Worth More Than the Workers’ Health?” The Guardian, April 16. | |

| Craciun, Maria (2020), “Migration of Romanians for Work During Restrictions Imposed by the Covid-19 Pandemic. Case Study: Romanians Leave to Pick Asparagus in Germany,” Revista Universitara de Sociologie, vol. XVI, no. 1. | |

| Digi24 (2020a), “After a Month of Hard Work on a Farm in Germany, a Romanian Woman Returns Home for Only 100 Euros: Ancuta’s Story,” July 20, available at https://www.digi24.ro/stiri/externe/dupa-o-luna-de-munca-grea-la-o-ferma-germana-o-romanca-se-intoarce-acasa-cu-doar-100-de-euro-povestea-ancutei-1340579, viewed on November 25, 2020. | |

| Digi24 (2020b), “The Drama of the Romanian Seasonal Workers from a Farm in Bavaria: ‘People with Coronavirus, Taken to Work with Japca. He Said There Was No Hotel for Him’,” Aug 19, available at https://www.digi24.ro/stiri/actualitate/drama-sezonierilor-romani-de-la-o-ferma-din-bavaria-oameni-cu-coronavirus-dusi-la-munca-cu-japca-a-spus-ca-nu-i-hotel-la-el-1355628, viewed on November 25, 2020. | |

| Durazzi, Niccolo, Fleckenstein, Timo, and Lee, Soohyun Christine (2018), “Social Solidarity for All? Trade Union Strategies, Labor Market Dualisation, and the Welfare State in Italy and South Korea,” Politics and Society, vol. 46, no. 2, pp. 205–33. | |

| European Commission (2019), “Income of EU Cereal Farms Increased in 2017,” Agriculture and Rural Development, European Commission, Brussels, Dec 20, available at https://ec.europa.eu/info/news/income-eu-cereal-farms-increased-2017-2019-dec-20_de, viewed on November 25, 2020. | |

| Eurostat (2020), “Disparities in Minimum Wages Across the EU,” Feb 3, available at https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/products-eurostat-news/-/DDN-20200203-2, viewed on October 10, 2020. | |

| Filip, Răzvan, and Vorreyer, Thomas (2020), “Prin ce trec muncitorii români în Germania, ca să aibă o viață decentă în România,” Vice, May 26, https://www.vice.com/ro/article/ep4n4w/joburi-pentru-muncitorii-romani-in-germania, viewed on November 24, 2020. | |

| Forbes Romania (2020), “Germany: Hundreds of Romanians at Risk of Being Infected with Covid-19. The Farm He Works on Has Been Quarantined,” July 27. | |

| Fraser, Evan D. G., and Stringer, Lindsay C. (2009), “Explaining Agricultural Collapse: Macro-Forces, Micro-crises and the Emergence of Land Use Vulnerability in Southern Romania,” Global Environmental Change, vol. 19, no. 1, pp. 45–53. | |

| Gabor, Daniela (2010), Central Banking and Financialization: A Romanian Account of How Eastern Europe Became Subprime, Palgrave Macmillan, Hampshire. | |

| García-Colón, Ismael (2020), “The Covid-19 Spring and the Expendability of Guestworkers,” Dialectical Anthropology, July 29, pp. 1–8. | |

| Hecking, Claus, and Klawitter, Nils (2020), “The Weissenfels Swamp,” Der Spiegel, Sept 23, available at https://www.spiegel.de/wirtschaft/soziales/razzia-in-der-fleischindustrie-der-sumpf-von-weissenfels-a-c82d7da6-7352-45ca-995b-61379778a966?fbclid=IwAR0kT12NQ7hh2cp7YPHFKOm1ir4JGIDSmcK5EesP6gnxJb2-7jUlf-ETnH4, viewed on October 16, 2020. | |

| Helgadóttir, Oddný (2016), “The Bocconi Boys Go to Brussels: Italian Economic Ideas, Professional Networks and European Austerity,” Journal of European Public Policy, vol. 23, no. 3, pp. 392–409. | |

| Hessenschau (2020), “Visiting Harvest Workers,” May 23, available at https://www.hessenschau.de/tv-sendung/zu-besuch-bei-erntehelfern,video-122784.html?fbclid=IwAR0qDVMG5qJQ54PNpV8wvfqTFZkcmrryvt9LbXpmT2z9v3uQKOGdK-juDzs, viewed on October 22, 2020. | |

| Horváth, István (2008), “The Culture of Migration of Rural Romanian Youth,” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, vol. 34, no. 5, pp. 771–86. | |

| International Organization for Migration (IOM) (2019), World Migration Report 2020, available at https://publications.iom.int/system/files/pdf/wmr_2020.pdf, viewed on October 10, 2020. | |

| Jacobs, Louisa (2020), “Und Wer Rettet die Erntehelfer?” Die Zeit, June 4. | |

| Kasimis, C. (2008), “Survival and Expansion: Migrants in Greek Rural Regions,” Population, Space and Place, vol. 14, no. 6, pp. 511–24. | |

| Kasimis, C., Papadopoulos, A. G., and Pappas, C. (2010), “Gaining from Rural Migrants: Migrant Employment Strategies and Socioeconomic Implications for Rural Labour Markets, Sociologia Ruralis, vol. 50, no. 3, pp. 258–76. | |

| Kideckel, David A. (2010), “România Postsocialistă. Munca, Trupul si Cultura Clasei Muncitoare,” Iasi, Polirom. | |

| Kühnel, Alina (2020), “Romanian Seasonal Workers: Not Everyone Is Welcome in Germany,” Deutsche Welle, May 18, available at https://www.dw.com/ro/sezonierii-rom%C3%A2ni-nu-to%C5%A3i-sunt-bineveni%C5%A3i-%C3%AEn-germania/a-53477080?maca=ro-Facebook-sharing&fbclid=IwAR1EiKzt5FVxMmj-r6AVG-s5uoIUp-HiqINgEl5jTI2_BgDesHe_07_BBo0, viewed on October 22, 2020. | |

| Markiewicz, Olga (2019), “Stuck in Second Gear? EU Integration and the Evolution of Poland’s Automotive Industry,” Review of International Political Economy, vol. 27, no. 5, pp. 1–23. | |

| Mateoc-Sîrb, Nicoleta, Mateoc, Teodor, Mănescu, Camelia, and Grad, Ioan (2014), “Research on the Labour Force from Romanian Agriculture” Scientific Papers Series Management, Economic Engineering in Agriculture and Rural Development, vol. 14, no. 1, pp. 215–18. | |

| Mihăilescu, Vintilă (2018), Etnogeneză si Tuică, Polirom, Iasi. | |

| Mummert, Annette, and Friedrich Schneider (2002), “The German Shadow Economy: Parted in a United Germany?” Finanz Archiv/Public Finance Analysis, vol. 86, no. 3, March, pp. 286–316. | |

| Nahoi, Ovidiu (2020), “When Germany Discovers the Exploitation of Seasonal Workers,” RFI Romania, July 28, available at https://www.rfi.ro/politica-123488-cand-germania-descopera-exploatarea-sange-sezonieri, viewed on October 22, 2020. | |

| National Institute of Statistics (INS) (2018), Anuarul Statistic al României [Romanian Statistical Yearbook], Bucharest. | |

| National Institute of Statistics (INS) (2020), “Earnings - Since 1991, the Monthly Series,” available at https://insse.ro/cms/ro/content/c%C3%A2%C8%99tiguri-salariale-din-1991-serie-lunar%C4%83, viewed on October 10, 2020. | |

| Neef, Andreas (2020), “Legal and Social Protection for Migrant Farm Workers: Lessons from Covid-19,” Agriculture and Human Values, no. 37, pp. 641–2. | |

| Palzer, Kerstin (2020), “Heiß, Laut und Aggressive,” Tagesschau, May 24. | |

| Peine, Hubertus Heil (2020), “Current Hour: Working Conditions in the Meat Industry,” Speech by Federal Minister for Labour and Social Affairs, The Bundestag, Bonn, May 13, available at https://www.bundestag.de/mediathek?videoid=7445329&fbclid=IwAR2fSjzex-MoY6Hx61YQaucDmekYz_jYWn2WgZkSpIdGP6lVEjUujCHOgoQ#url=L21lZGlhdGhla292ZXJsYXk/dmlkZW9pZD03NDQ1MzI5&mod=mediathek, viewed on November 25, 2020. | |

| Perez, Sofia A., and Matsaganis, Manos (2018), “The Political Economy of Austerity in Southern Europe,” New Political Economy, vol. 23, no. 2, pp. 192–207. | |

| Petrovici, Norbert (2013), “Neoliberal Proletarisation Along the Urban-Rural Divide in Postsocialist Romania,” Studia UBB Sociologia, vol. LVIII, no. 2, pp. 23–54. | |

| Pitu, Lavinia (2020), “Video: System Operation,” Deutsche Welle, July 27, available at https://www.dw.com/ro/exploatare-cu-sistem-%C3%AEn-germania/a-54330087, viewed on November 25, 2020. | |

| Pitu, Lavinia, and Schwartz, Robert (2020), “Germany’s Exploited Foreign Workers Amid Coronavirus,” Deutsche Welle, July 29, available at https://www.dw.com/en/germanys-exploited-foreign-workers-amid-coronavirus/a-54360412, viewed on October 22, 2020. | |

| Popovici, Elena Ana, Bălteanu, Dan, and Kucsicsa, Gheorghe (2016), “Utilizarea terenurilor si dezvoltarea actuală a agriculturii,” in Bălteanu, D., Dumitraşcu, M., Geacu, S., Mitrică, B., and Sima, M. (eds.), România: Natură si Societate, Romanian Academy Publishing House, Bucharest, pp. 329–374. | |

| Rye, Johan Fredrik (2014), “The Western European Countryside from an Eastern European Perspective: Case of Migrant Workers in Norwegian Agriculture,” European Countryside, vol. 6, no. 4, pp. 327–46. | |

| Rye, Johan Fredrik, and Andrzejewska, Joanna (2010), “The Structural Disempowerment of Eastern European Migrant Farm Workers in Norwegian Agriculture,” Journal of Rural Studies, vol. 26, no. 1, pp. 41–51. | |

| Rye, Johan Fredrik, and Scott, Sam (2018), “International Labour Migration and Food Production in Rural Europe: A Review of the Evidence,” Sociologia Ruralis, vol. 58, no. 4, pp. 928–52. | |

| Sandt, Julika (2020), “Süddeutsche Zeitung: FDP Calls for Better Hygiene Controls,” May 12, available at https://jsandt.mdl.fdpltby.de/suddeutsche-zeitung-fdp-fordert-bessere-hygienekontrollen?fbclid=IwAR1XgYThWu5KlWtFGou5brSMfiPRXFqtkIwLjAm02QXz3ZBdvf8a6DmmvUY, viewed on November 25, 2020. | |

| Sandu, Dumitru (1999), Spatiul Social al Tranziriei, Polirom, Iasi. | |

| Sandu, Dumitru (2010), Lumile Sociale ale Migraiei Românesti în Străinătate, Polirom, Bucharest. | |

| Solomon, Erika (2020), “Germany Tightens Abattoir Laws Following Virus Outbreaks,” Financial Times, July 29, available at https://www.ft.com/content/7b207e88-13d2-461e-8e5a-7884de34b40f, viewed on November 25, 2020. | |

| Spotmedia (2020), “Germany Announces Checks and Fines on Companies That Have Romanian Employees: All Workers Should Benefit from Fair Working Conditions,” Aug 13, available at https://spotmedia.ro/stiri/economie/germania-anunta-controale-si-amenzi-la-firmele-care-au-angajati-romani-toti-lucratorii-sa-beneficieze-de-conditii-corecte-de-munca, viewed on October 22, 2020. | |

| Stoica, Daniela (2019), “Dozens of Romanian Agricultural Workers Revolted on a Farm in Germany: ‘We Were Fooled’,” Rotalianul, July 31, available at https://www.rotalianul.com/zeci-de-muncitori-agricoli-romani-s-au-rasculat-la-ferma-din-germania/, viewed on October 22, 2020. | |

| Tenter, Oana (2020), “Exploitation from the Plate: How Romanians Work on Farms in Great Britain,” Scena9, June 22, available at https://www.scena9.ro/article/muncitori-sezonieri-pandemie-exploatare-migratie, viewed on October 22, 2020. | |

| Troc, Gabriel (2016), “Transnational Migration and Post-Socialist Proletarianisation in a Rural Romanian Province,” Studia UBB Europaea, vol. LXI, no. 3, pp. 51–66. | |

| United Nations (UN) (2018), World Urbanization Prospects: The 2018 Revision, Online Edition, Population Division, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, available at https://population.un.org/wup/Download/, viewed on December 2, 2020. | |

| Van Galen, Michiel, and Hoste, Robert (2016), “Profit Analysis in Animal Product Supply Chain: Exploratory Research and Proposal for a Generic Approach,” Memorandum No. 2016-052, LEI Wageningen UR, Wageningen, available at https://edepot.wur.nl/382676, viewed on November 25, 2020. | |

| Voicu, Bogdan (2006), “Satisfactia cu viata în satele din România,” in Sandu, Dumitru (ed.), Euro Barometrul Rural: Valori Europene în Sate Românesti, Open Society Foundation, Bucharest, pp. 7–20. | |

| Voivozeanu, Alexandra (2019), “Precarious Posted Migration: The Case of Romanian Construction and Meat-Industry Workers in Germany,” Central and Eastern Europe Migration Review, vol. 3, pp. 1–15. | |

| Westbrock, Sven, and Meurer, Christoph (2020), “Spargel Ritter Verweigert Gewerkschaftern den Zutritt,” General Anzeiger, May 18. | |

| Yapici, Sebile (2020), “Labour and the Love of Asparagus: A German Panic,” Gastronomica, vol. 20, no. 3, p. 97. |