ARCHIVE

Vol. 7, No. 1

JANUARY-JUNE, 2017

Research Articles

Research Notes and Statistics

Book Reviews

Recent Social Policies and Rural Development in Brazil:

The Family Allowance Programme in Rural Areas

*Universidad e Federal do Pampa, Campus Itaqui/Rio Grande do Sul, jonasanderson@ig.com.br

†Universidad e Federal do Rio Grande do Sul, Rio Grande do Sul.

‡Empresa Brasileira de Pesquisa Agropecuária (EMBRAPA), Petrolina.

§Universidad e Estadual do Rio Grande do Norte, Campus Assu/Rio Grande do Norte.

‖Universidad e Federal do Rio Grande do Sul, Rio Grande do Sul.

Abstract: Brazil won international renown in the first decade of the twenty-first century for reducing social inequalities and hunger, poverty, and extreme poverty. The Bolsa Família Programme played a significant role in this achievement. This article discusses public policy based on direct income transfer in Brazil and its role in poverty reduction, with special focus on outcomes in rural areas in the southern and north-eastern regions of the country. The article uses a theoretical framework that views development from the perspective of the social actors involved. The methodology of this research is based on data collected from the TABCad software of government departments responsible for the policies, as well as information gathered from fieldwork. The findings corroborate the importance of the Bolsa Família Programme in achieving advances in Brazil in the study period. They show that the impact of the Programme on rural populations and in the north-eastern region of the country has been notable, and can be attributed to a policy that focuses on social security as well as development.

Keywords: Bolsa Família, social policies, family allowance, Brazil, rural poverty, social development, inclusive development.

Introduction

The last 20 years have seen significant advances in rural development in Brazil, the results of which have not been sufficiently studied or understood as yet. Despite these advances, it is uncertain whether the policies that contributed to this progress will continue into the future. Since mid-2015, Brazil has been in the midst of an economic crisis that led to the impeachment of President Dilma Roussef in 2016. Similar proceedings were initiated against her successor, Michel Temer, the following year.

The period between 2005 and 2015 saw significant achievements in development in Brazil, which have been undermined by political, economic, and institutional crises in the country in the last two years. The foundations of macroeconomic stabilisation were laid in the 1990s and early 2000s, with the adoption of a new national currency and a greater regulatory role played by the state under the Fernando Henrique Cardoso (FHC) government (1994–2002). After the assumption of power by President Lula in 2003, the economic policy of the previous period continued, along with significant investment in social welfare policies. This intervention allowed the middle classes to increase their purchasing power through real increases in minimum wages. Moreover, lower-income sections of the population were included in direct cash payment schemes and food security policies. Public spending during the term of the Lula government was boosted by a boom in the commodity prices of soy, steel, and other goods, and the discovery of deep-sea oil reserves. As a result Dilma Roussef, the candidate of Lula’s governing party (the Workers’ Party), was elected to the Presidency for two consecutive terms, the second term being interrupted by her impeachment in 2015, when the model of economic growth based on wealth distribution and social policies collapsed. Analysts agree that the current economic crisis in Brazil is in part a delayed effect of the 2008 international crisis, aggravated by allegations of corruption in the financing of political campaigns. Since mid-2015, Brazil has faced economic stagnation combined with a loss of political legitimacy, which led to the impeachment of Dilma Roussef and a shift to right-wing policies under the Temer government.

The fact remains, however, that Brazil is one of the few countries of the world to have achieved the Millennium Development Goals set in 2000. Its efforts in the struggle against poverty met with success in the first decade of the twenty-first century, and have been recognised by the United Nations (FAO 2015; FAO et al. 2015a, 2015b) and other international organisations. This was achieved by a combination of factors: in particular, the role played by the state, and public policies that focused on inclusion and promotion of social protection. State action and public policies were fundamental to the development of a “Brazilian model” of inclusive social development (Amann and Barrientos 2015).

The Brazilian model of inclusive development combines policies of social protection and wealth distribution mechanisms. The 2012 report of the High Level Panel of Experts on Food Security and Nutrition (HLPE 2012) defines this process as one that creates a “social protection system” by establishing food security and reducing vulnerability (poverty and hunger) in order to safeguard the right to food. In this model, both agriculture and food production systems are strategic for linking smallholder farmers to markets and ensuring food supply (ibid., p.16). França et al. (2016) have described the approach as a combination of social protection policies, economic development, and wealth distribution.

The primary measure adopted to reduce absolute poverty among disadvantaged sections of the population was a policy of conditional cash transfers, known as the Bolsa Família Programme, instituted at the end of 2003.1 Souza et al. (2015) note the importance of the Programme in ensuring a minimum income for poor and extremely poor families. It ensures a minimum income or family allowance for poor families (monthly income per person between R$ 77 and R$ 154) and extremely poor families (monthly income per person of upto R$ 77), subject to the fulfilment of some conditions. The Bolsa Família Programme was integrated with the Brazil Without Extreme Poverty Plan (Plano Brasil sem Miséria or BsM) launched in 2011, which combined different social programmes that focused on extremely poor families. The BsM Plan has three components: access to services, guaranteed income, and inclusion, and is an extension of the Territories of Citizenship Programme (Programa Territórios da Cidadania), established in 2008 for promoting economic development, universal access to services, and other basic social rights. This was implemented using a sustainable territorial development strategy that focused on rural areas.

In 2013, a new scheme named Caring Brazil (Brasil Carinhoso) was launched. It supplemented the BsM Plan and had three components: income, education, and health. For income, an allowance aimed at alleviating extreme poverty in early childhood was allocated to families with infants and young children, and was paid in conjunction with family allowance; for education, the number of seats in day-care centres was increased; and for health, measures were taken to address the problem of diseases affecting infants.

The years between 2001 and 2011 were termed the “inclusive decade” in Brazil. In this period, the incomes of the poorest sections increased by about 90 per cent, and the income of the richest section by 16 per cent. This resulted in a fall in inequality (IPEA 2012). According to Campello (2014), chronic poverty in Brazil fell from 8.3 per cent in 2002 to 1.1 per cent in 2013.

Scholars have studied public policies and strategies undertaken for poverty alleviation in Brazil to better understand these results. They confirm that the Bolsa Família Programme has been instrumental in the reduction of poverty in the country (Lavergne and Beserra 2016; Paiva et al. 2016). Several studies have also analysed beneficiaries’ compliance with the requirements for school attendance (Brauw et al. 2015), the use of allowance money for purchasing food (Bortoletto 2013; Duarte et al. 2009), and its impact on nutrition and health (Rasella et al. 2013). All these indicate positive results.

Nevertheless, studies on and analyses of the relationship between agriculture and social policies, and especially the effects of social protection policies on beneficiary families in rural areas, are scarce. Devereux and Sabates-Wheeler (2004) and Tirivayi et al. (2014) indicate that various barriers hinder the beneficiaries of social protection policies from inclusion in rural development policies, and that compatibility between the two is not easy to achieve.

This article discusses the Bolsa Família Programme, and analyses its contribution to reducing poverty and inequality in Brazil in recent years, with special attention to results in rural areas in the southern and north-eastern regions of the country. The south shows the lowest levels of rural poverty while the highest levels are in the north-east.

This study is based on a theoretical approach that assumes coordination between social protection policies and development policies as being a condition for the advance of disadvantaged populations, especially in rural areas. The methodology of the analysis is based on data collected from the TABCad software of government departments in Brazil responsible for these policies, as well as information collected during fieldwork.

The article is organised into five sections, including the introduction. In the second section, we contextualise the main social policies implemented in Brazil in recent years, some aspects of the origin and evolution of the Bolsa Família Programme, the evolution of social indicators in Brazil, and limits to the effectiveness of the policy of income transfer because of its poor connection with other policies on inclusion. The third section analyses the scope of the Bolsa Família Programme in rural areas in the southern and north-eastern regions of Brazil. The fourth section discusses the outcomes of the policies, drawing lessons from the Brazilian experience of the relationship between social policy and development. In the final section, we outline new challenges posed by the current national political context.

The Expansion of a Welfare State in Brazil

Between 2000 and 2012, social policies in Brazil underwent a significant expansion, leading some scholars to characterise the process as the development of a “welfare state” (Campello et al. 2014; Neri 2010).

This led to a debate on the emergence of a “new middle class” in Brazil as a result of the interaction between social protection policies and policies aimed at promoting development – such as those that prepare workers for jobs, generate income, and provide access to credit. This interpretation, using income as an indicator of upward social mobility, was developed by researchers from the Institute for Applied Economic Research (IPEA). It was estimated that there was a 39 per cent increase in population in the R$ 1,276 to R$ 5,104 income range, in the period between 2004 and 2012 (Barufi 2012).2

Neri (2012) uses monetary income as a parameter of analysis, and points to a growth of 71.8 per cent in the income of the rural middle class in the period between 2003 and 2009. There is consensus among scholars (Castro 2011; Neri 2010; Neri 2013; Osório 2011) that the social mobility observed in the country during the first decade of the twenty-first century was a result of government initiatives aimed at increasing the minimum wage, boosting consumption by reducing taxes, facilitating access to credit, and income transfer programmes.

This definition of mobility has been criticised for disregarding important sociological elements in the definition of class, such as schooling and occupation (Souza 2006). Souza (2009, 2010) has challenged this approach, claiming that the Brazilian “new middle class” comprises a section of workers who have limited opportunities for upward social mobility as they generally perform low-skilled and poorly-paid work. By contrast, Singer (2015) suggests that the “new middle class” in Brazil would be the new proletariat, comprising skilled and educated workers engaged in formal work, despite receiving low salaries.

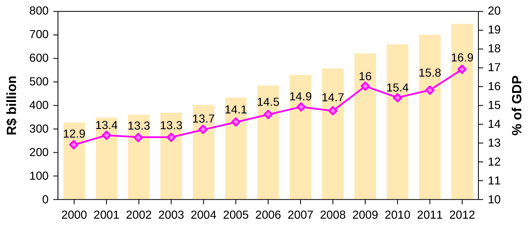

Figure 1 shows the substantial increase in social spending in Brazil between 2000 and 2012, when resources allocated to social policies grew both in real terms and as a percentage of GDP: from R$ 326 billion (12.9 per cent of GDP in 2000) to R$ 744 billion (16.9 per cent of GDP in 2012).

Figure 1 Growth in social spending in the Federal Government budget of Brazil in R$ billion at 2012 prices and as percentage of GDP

Source: SIOP/MP and ContaNacional/IBGE, and elaborated by CAISAN (2014).

The strategic growth in resources allocated to distributive policies during the period under study contributed to strengthening a “social protection network” that favoured the most disadvantaged sections in Brazilian society (França et al. 2016; Silveira 2016). This social protection network has had a positive impact on the living conditions of families while at the same time boosting the domestic market. In rural areas in particular, policies that contributed to improving the living conditions of the poorest sections were rural pensions and various programmes aimed at small family farmers. These include the National Programme for Strengthening Family Farming (PRONAF) and schemes under the BsM Plan, in particular the Bolsa Família Programme.3

The rural pension system in Brazil has been universal since the first half of the 1990s. It consists of the payment of a monthly cash allowance of at least one official minimum wage to elderly male and female family farmers.4 In terms of coverage, in 2012, the system paid 8.5 million pensions totalling R$ 60.9 billion, half of which benefited family farmers in peripheral areas of the north-eastern region, which perform the worst in Brazil’s social indicators (Silveira 2016).

Alongside rural social security, another important instrument that contributed to the expansion of social spending in Brazil was PRONAF. This Programme was created in 1996 with the aim of promoting the sustainable development of Brazilian family farmers who, according to the latest Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatistica (IBGE) survey, comprise 4.4 million small farming units and represent 84 per cent of the 5.2 million agricultural establishments in the country (Aquino and Schneider 2015). According to Silveira (2016), PRONAF awarded nearly 1.8 million agricultural contracts for financing operational costs and investments at subsidised interest rates that, taken together, amount to almost R$ 25 billion.

The largest concentration of PRONAF’s resources lies in the southern region in Brazil, where organised and capitalist family farmers are located (Aquino and Bastos 2015). This can be better understood by examining the structure of agricultural production in Brazil. Two distinct segments coexist here: the first is agri-business based on large entrepreneurial estates, and specialising in the production of commodities for export and domestic consumption; the second is family farming, comprising farmers who own small plots of land – and whose production is diversified and focused on both domestic consumption and export, and integrated with agro-industrial systems.

Among the public policies recently adopted in Brazil, the Bolsa Família Programme stands out as the third most important source of income for poor families in the countryside (Silveira 2016). The Programme benefits poor and extremely poor populations that have been historically excluded from social progress. Its intervention strategy, discussed below, complements the role played by other government schemes, thus strengthening the social protection network that serves millions of disadvantaged families especially in rural areas.

The Bolsa Família Programme was created at the end of 2003, with the objective of reducing poverty in the medium and long term through a system of cash transfer and opportunities for the socio-economic inclusion of beneficiaries (Castilho e Silva 2014). It operates on the basis of four pillars: (i) direct cash transfers to beneficiaries (there are no middle agents, either public or private); (ii) payment via a financial system that has been adapted to serve millions of families previously excluded from the banking system; (iii) priority for payments accorded to women, who function as their families’ referees for accessing resources; and (iv) compliance by families with conditions related to education and health in order to remain in the Programme and access basic social rights (Campello and Neri 2013).

In 2016, the basic allowance under the Bolsa Família Programme was R$ 85, paid to families whose monthly per capita income did not exceed R$ 85. Variable benefits add to the basic allowance and are limited to five children (up to the age of 15), nursing mothers or pregnant women who receive a payment of R$ 39 each, and families whose monthly per capita income does not exceed R$ 170 receive R$ 46 each. If a family remains in extreme poverty despite the allowances, it receives a further benefit earmarked for overcoming extreme poverty that is calculated on an individual basis.

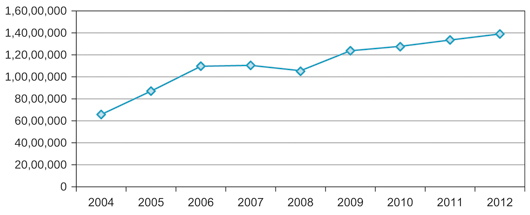

There was an increase in the coverage of the Bolsa Família Programme between 2004 and 2012 (Figure 2). In 2004, the Programme granted a total of 6,571,839 family allowances. In 2012, this figure reached 13,900,733, representing an increase of 111.5 per cent.

Figure 2 Growth in the number of beneficiaries of family allowances in Brazil, 2004–12

Source: Computed by the authors from data from IPEADATA (2014).

Owing to the wide reach of the income transfer programme, Castro et al. (2011) argue that it can be understood as a development strategy, since the resources invested in it have had a significant return in the form of increase in gross domestic product (GDP) and decrease in social inequality. Similarly, Kerstenetzky (2009) attributes a strategic character to the Programme with regard to opportunity costs, as future returns from current investments in the population exceed present costs. Thus, the sum of all outcomes tends to result in a cumulative process of improvement in the quality of life of the targeted population.

Despite the significant advances in social development that the Bolsa Família Programme has achieved, Hall (2008, 2012) suggests that its political implications should be taken into account. The author highlights the electoral use of the Programme, which feeds into clientelistic relationships and increased economic dependence of beneficiaries on it. This slows down the process of promoting citizenship and creating productive jobs for the population. Originally intended to address poverty and extreme poverty, the Programme has assumed the nature of the sole policy instrument with which to resolve social problems in the country.

Official data indicate a substantial improvement in Brazilian social indicators between 1992 and 2012 (CAISAN 2014; Campello et al. 2014). Poverty and extreme poverty in the country fell to less than half of levels in 1992. In 2002, extreme poverty affected 8.8 per cent of the population; the corresponding figure for 2012 was 3.5 per cent. In 2002, poverty affected 24.2 per cent of the population, a figure that decreased to 8.5 per cent in 2012.

Alongside the decrease in poverty, significant upward social mobility was also observed among the poorest sections of the population. The factors behind this were a rise in the minimum wage above the rate of inflation, an increase in labour income, greater formalisation of the labour market, and a rise in the value of family allowances – all of which contributed towards reducing the Gini coefficient of Brazil’s income distribution (Neri 2013) from 0.553 in 2002 to 0.5 in 2012 (CAISAN 2014).

In addition, Severe Food Insecurity, as measured by Escala Brasileira de Insegurança Alimentar (the Brazilian Food Insecurity Scale, an index that measures the perception of families regarding their access to food),5 fell from 6.9 per cent in 2004 to 5 per cent in 2009, while food security, which was 65 per cent in 2004, increased to 69.7 per cent in 2009 (CAISAN 2014). Though food deprivation remains a problem, the living conditions of the population improved during this period, contrary to what Souza et al. (2015) have noted on the relation between a hike in food prices and incomes.

These results describe the history of food and nutritional security in Brazil, especially from the mid-1990s, when the Brazilian state began to address this problem. The establishment of the National Food Security Plan and the creation of the National Council for Food Security (CONSEA) in 1993 marked the beginning of a new strategic approach to food security. This was subsequently reinforced by the Zero Hunger Programme in 2003, and the Food and Nutrition Security System (SISAN) in 2006.

These policies marked the strategic nature of the government’s approach to the problem and the concern of the state in addressing a historical social ill. A combination of social assistance and inclusion policies became the primary method to tackle poverty. The initiatives developed the ideas of Josué de Castro, renowned Brazilian physician who, in 1946, had noted that access to adequate food was a sine qua non for the development of a country. Castro, who later became the Director-General of the Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) of the United Nations, had realised how persistent malnutrition and hunger, even if hidden, could make development unattainable (Castro 1984).

It is worth emphasising that food and nutrition security constitutes an important dimension of the Bolsa Família Programme. Access to it has played a central role in the progress related to social indicators in Brazil by guaranteeing a minimum income for the poorest sections. This in turn has meant greater access to food as well as an improvement in the nutritional quality of diets (Bortoletto 2013). However, a study conducted after 12 years of the Programme’s implementation concluded that the beneficiaries remain dependent on it instead of rising above the threshold of poverty. This observation was based on a slight increase in extreme poverty in the country, from 3.6 per cent to 4 per cent between 2012 to 2013 (IPEA 2015), but can be attributed to the fact that at the time of research, the value of the allowance had not been adjusted for and there was a decrease in labour income due to an economic slowdown.

Despite considerable advances in development since the inception of direct income transfer policies in Brazil, especially since the integration of these policies with the Bolsa Família Programme, issues surrounding implementation have received scant attention. These relate to the targeting of beneficiaries, lack of inter-ministerial coordination, difficulties in monitoring the Programme, and the political and economic implications of the Programme (Hall 2006, 2008, 2012).

Moreover, few studies have evaluated the effects of the Bolsa Família Programme on rural beneficiaries. Some information on the effects of the Programme on schooling, educational performance of children, and integration in the job market is available in a study by Mello and Duarte (2010), and shows how the Programme has had a positive effect on enhancing children’s school attendance, especially among girls. Another study (Nunes and Mariano 2015) points to a fall in the search for non-agricultural work by beneficiary families. This includes younger members who are enrolled in school and no longer seek jobs outside the household, and heads of households who prioritise work within their agricultural units to meet the conditions for continuance of the supplementary income.

In one of the few studies on the functioning of the Bolsa Família Programme in rural areas with high poverty rates, Favero (2011) shows how cash transfers affect the dynamics of the local market and the daily life of the community with regard to improvement in consumption. The region under study here is the Territory of Identity of Jacuípe Basin (TIBJ), a semi-arid region in north-eastern Brazil. Having experienced a prolonged spell of drought, income from the Bolsa Família Programme has served as a guarantee for the purchasing power of poor families in the TIBJ.

Some analysts have pointed out that the Bolsa Família Programme could have had more robust results if it had been linked to other policies on inclusion. Parsons (2015) claims that despite its cost-effectiveness, the Programme has not responded effectively to the needs of a population living in persistent poverty in remote rural municipalities, where services are either non-existent, or difficult to access and of low quality.

A recent work on the compatibility between the rural credit policy, PRONAF, and inclusion strategies in the BsM Plan finds “strong suggestions of possible synergies between a rural credit programme and a cash transfer programme” (Garcia et al. 2016, p. 109). The authors note that rural families that simultaneously benefited from the Bolsa Família Programme and credit from PRONAF performed better in terms of productivity and agricultural income than families that benefited from only one policy or neither. Only a small proportion of low-income rural producers in the country, however, enjoy the benefits of such integration.

The Reach of the Bolsa Família Programme in Rural Areas in the North-East and the South

In this section, we present some results from an analysis of two regions that are representative of Brazil’s geographic and social diversity. The north-east of the country registers a higher incidence of poverty, whereas the southern region is one of the richest in the country, but has a significant number of families living in poverty and extreme poverty.

Data from CadÚnico (Unified Register for Social Programmes) show the reach of the Bolsa Família Programme across the country.6 In December 2014, the Programme supported 13.9 million families, most of which were concentrated in the north-eastern region (Table 1). The percentage of urban families under the Programme in all regions is higher than that of rural families, following the pattern of population distribution in the country. The urban–rural difference is more evident in the south-east and the central-western regions. Overall, the number of rural families covered by the Programme amounted to 3,786,645 or 27.1 per cent of the total number of beneficiary families. For the northern and north-eastern regions, this percentage was higher than the national average, with beneficiaries comprising over 30 per cent of rural families in both regions, whereas only 19.9 per cent of beneficiary families in the southern region lived in rural areas.

Table 1 Distribution of beneficiary families (urban and rural) under the Bolsa Família Programme in December 2015 in number and per cent

| Region | Total number of families under the Programme | Urban allowances | Rural allowances | No answer | |||

| Number of families | Percentage of families | Number of families | Percentage of families | Number of families | Percentage of families | ||

| North | 1,715,911 | 1,170,810 | 68.2 | 544,761 | 31.7 | 340 | 0.02 |

| North-east | 7,029,486 | 4,536,287 | 64.5 | 2,489,921 | 35.4 | 3,278 | 0.05 |

| South-east | 3,559,909 | 3,072,494 | 86.3 | 458,818 | 12.9 | 28,597 | 0.8 |

| South | 937,572 | 745,303 | 79.5 | 186,409 | 19.9 | 5,860 | 0.6 |

| Centre-west | 726,267 | 618,042 | 85.1 | 106,736 | 14.7 | 1,489 | 0.2 |

| Brazil | 13,969,145 | 10,142,936 | 72.6 | 3,786,645 | 27.1 | 39,564 | 0.3 |

Source: MDS/CadÚnico/TABCAD (2016). Computed by the authors.

While rural Brazil registers a higher incidence of poverty, it also presents some special features. A study by Soares found that poverty and extreme poverty had a greater impact on households headed by women and young persons, and where members did not fall under the categories of employer, employee, or self-employed. The study also showed how poverty and extreme poverty are more persistent in pluriactive households, whose members are included in the “other” category, i.e. day labourers or informal workers. The highest rates of poverty and extreme poverty in Brazil occur mainly among non-farming households in rural areas. Thus, data on the nature of rural poverty in Brazil are representative of the precarious situation of daily labourers and informal workers, and indicate a need for policies designed for this section of the population.

The north-eastern region in Brazil has the highest rates of poverty. The reasons for this are partly natural: large tracts of land that cannot be used for agriculture, problems of irrigation and irregular rainfall; and partly the history of occupation and exploitation of the territory. It is not surprising that over half the number of families under the Bolsa Família Programme reside in this region, although these factors add to the difficulty in overcoming poverty. The Programme covers 40.1 per cent of the population in the region, of which 37.4 per cent live in rural areas (Table 2). This high proportion is evidence of the importance of the Programme in the region.

Table 2 Distribution of beneficiaries under the Bolsa Família Programme in rural and urban localities in north-eastern States, in July 2016 in number and per cent

| State | Total number of beneficiaries | Programme beneficiaries as a percentage of total population | Number of rural beneficiaries | Rural beneficiaries as a percentage of all beneficiaries | Number of urban beneficiaries | Urban beneficiaries as a percentage of all beneficiaries | Rural population (in number) | Rural population as a percentage of total population | Total population |

| Alagoas | 1,330,775 | 39.6 | 485,131 | 36.5 | 845,49 | 65.5 | 822,634 | 24.5 | 3,358,963 |

| Bahia | 5,869,238 | 38.4 | 2,299,768 | 39.2 | 3,568,594 | 60.8 | 3,914,430 | 25.6 | 15,276,566 |

| Ceará | 3,511,848 | 39.2 | 1,382,899 | 39.4 | 2,127,691 | 60.6 | 2,105,824 | 23.5 | 8,963,663 |

| Maranhão | 3,388,532 | 48.7 | 1,410,391 | 41.6 | 1,977,950 | 58.4 | 2,427,640 | 34.9 | 6,954,036 |

| Paraíba | 1,681,613 | −42 | 547,733 | 32.6 | 1,133,771 | 67.4 | 92,785 | 23.2 | 3,999,415 |

| Pernambuco | 3,536,967 | 37.6 | 1,040,952 | 29.4 | 2,495,486 | 70.6 | 1,744,238 | 18.5 | 9,410,336 |

| Piauí | 1,482,274 | 46.1 | 649,476 | 43.8 | 832,658 | 56.2 | 1,067,401 | 33.2 | 3,212,180 |

| Rio Grande do Norte | 1,162,584 | 33.4 | 380,312 | 32.7 | 781,864 | 67.3 | 703,036 | 20.2 | 3,474,998 |

| Sergipe | 862,293 | 38.1 | 330,876 | 38.4 | 531,189 | 61.6 | 547,651 | 24.2 | 2,265,779 |

| Total | 22,826,124 | 40.1 | 8,527,538 | 37.4 | 14,294,693 | 62.6 | 14,260,704 | 25 | 56,915,936 |

Source: MDS/CadÚnico/TABCAD (2016). Elaborated by the authors.

In contrast, the southern region has the lowest coverage under the Programme in proportion to its population. While this points to better living conditions in the region, the social precarity that persists among a significant section of the population cannot be disregarded.

An examination of States in the north-eastern region shows that at least one-third of the population in all States depended on the allowance, notably in Maranhão, where 48.7 per cent of the residents rely on income transfer (Table 2). More than meeting the multiple needs of disadvantaged populations, the Bolsa Família Programme plays the role of supporting an “economy without production” in the north-east (Maia Gomes 2001). This is especially true for rural populations, as beneficiary families comprise 37.4 per cent of total beneficiaries in the region but account for 59.8 per cent of its rural population (8,527,538 rural beneficiaries for a total rural population of 14,260,704).

The dependence of this population on social benefits should not be understood as indolence or reluctance to work; rather, it has to be viewed from a broader perspective. Environmental conditions that make the practice of agriculture in this semi-arid region difficult, a harsh climate, successive droughts, the agrarian history of Brazil that deprived the population in the region from access to land, and, finally, the neglect of this region by the Brazilian state, have to be taken into account. This region has the worst performance in the country in terms of the social indicators of literacy rates, schooling, and minimum qualifications for work, among other indicators of basic human rights and citizenship (Osório et al. 2011).

Similarly, a majority of farmers in north-eastern Brazil who are supported by PRONAF, the Programme that meets the credit needs of low-income farmers, fall within the lowest income bracket. They have greater access to credit in terms of the amount of finance granted. However, they access the lowest total value of credit among all regions, as the amount made available in the form of microcredit to each establishment is very small (Aquino and Bastos 2015; Silveira 2016).

In southern Brazil, a region comprising three States, the Bolsa Família Programme covers 10.7 per cent of the population. In the rural areas of the region, beneficiaries of cash transfers represent 15.7 per cent of the total rural population and 20.5 per cent of total beneficiaries (Table 3). Given the methodology of the research, data point to a lower incidence of poverty in the region. However, even in one of the most developed regions, the proportion of the population under poverty is still significant. Though the proportion is lower than in the north-east, the effects of income transfer are nonetheless significant for the economy in the south, especially in specific areas or micro-regions that are critically affected by poverty, making them as dependent on cash transfer as beneficiaries in the north-east (Schneider 2015).

Table 3 Distribution of beneficiaries of the Bolsa Família Programme in rural and urban localities in southern States, in August 2016 in number and per cent

| State | Total number of programme beneficiaries | Programme beneficiaries as a percentage of total population | Number of rural beneficiaries | Rural beneficiaries as a percentage of all beneficiaries | Number of urban beneficiaries | Urban beneficiaries as a percentage of all beneficiaries | Rural population (in number) | Rural population as a percentage of total population | Total population |

| Paraná | 1,346,543 | 12 | 290,906 | 21.7 | 1,053,166 | 78.3 | 1,531,834 | 13.6 | 11,242,720 |

| Rio Grande do Sul | 1,331,546 | 11.8 | 248,567 | 18.7 | 1,080,604 | 81.3 | 1,593,638 | 14.1 | 11,286,500 |

| Santa Catarina | 466,429 | 6.7 | 106,288 | 23 | 359,057 | 77 | 1,000,523 | 14.5 | 6,910,553 |

| Total | 3,144,518 | 10.7 | 645,761 | 20.5 | 2,492,827 | 79.3 | 4,125,995 | 14 | 29,439,773 |

Source: MDS/CADÚNICO/TABCAD (2016).

Studies such as Castro et al. (2011) conclude that social expenditure by the government has led to an increase of 1 per cent in national GDP. Based on this, we attempted to determine the economic cost of the Bolsa Família programme in the regions under study. Examining data on participation in the Programme and its impact on GDP, we observed that cash transfers represented 0.18 per cent of total GDP in the south and 1.75 per cent of GDP in the north-east, with the States of Piauí and Maranhão receiving cash transfers amounting to almost 3 per cent of GDP (Table 4).

Table 4 Resources transferred by the Bolsa Família Programme in 2015 to the southern and north-eastern regions as a proportion of GDP in 20147 in Brazilian Real and per cent

| Region | Resources in 2015 (R$) (1) | GDP in 2014 (R$) (2) | Bolsa Família Programme as a proportion of GDP (in per cent) (1/2) |

| South | 1,739,591,376 | 948,453,000,000 | 0.18 |

| North-east | 14,122,442,415 | 805,098,000,000 | 1.75 |

Source: IBGE – Estados – Contas Regionais do Brasil and computed by the authors.

Data further illustrate the relevance of the Bolsa Família Programme in some regions, especially in the north-east. It is evident that the reach of the Programme will increase in regions that are not economically dynamic and where the poorest beneficiaries live. Moreover, as production systems in Brazil favour a geographically concentrated creation of wealth (Lencione 2008), the Programme plays a redistributive role by transferring resources from more capitalised regions to a region that is less capitalised.

As poverty in Brazil is concentrated in rural areas (Neri 2012), the Bolsa Família Programme plays an important role in making these areas more productive by promoting local economies (beneficiaries purchase what they need in local markets), improving the quality of life and school education (beneficiaries use the resources for purchasing food, school supplies, and consumer goods) (Vieira et al. 2016). Rural economies where access to such items is difficult doubly benefit from the income transfer, which also functions as an investment in productive systems (Schneider 2015).

Lessons from the Brazilian Experience of Income Transfer and Rural Development

One of the challenges in analysing public policy is the institutional separation between social assistance policies and development policies, which views development as purely a matter of the economy. In contrast, the capability approach proposed by Sen (2000) understands development as an increase in the social welfare of populations and the opportunities available to them. The development of a nation is understood as development of its people. Welfare and development are interlinked with the former meeting the different needs of individuals, and the latter aimed at social inclusion by reducing dependence on the state and expanding opportunities.

Hall and Midgley (2004) note that improvement in the social and economic conditions of a population through coordinated action across social and developmental policies can develop human capital and increase the autonomy of beneficiaries. However, they acknowledge the limitations of such a mechanism for furthering development.

Integration between social and development policies has not been achieved in Brazil, mainly due to limitations of the national political structure and the resistance of policy-makers to change practices. The governing structure in Brazil has historically been organised according to a division of the administrative spheres into different ministries, and their distribution among political supporters of the elected President. This means that the policies and priorities of each sphere tend to be treated separately. Recent initiatives to achieve an inter-sectoral approach by coordinating the work of different ministries have had limited success, especially since the groups that operate the ministries do not have common interests, and mediators and technicians in different areas do not apply the same methods.

Despite the efforts of the Brazilian government to reduce poverty and improve the quality of life of its population, the connection between welfare and inclusive development needs to advance further. While 3.1 million families have voluntarily left the Bolsa Família Programme, because of what can be considered an improvement in their quality of life, Brazil still has around 50 million people who depend on the Programme in order to rise above the threshold of extreme poverty.

In this context, new strategies of inclusion and deeper links between existing policies have to be developed. Limitations in the implementation of these policies at local levels, and ways to improve the mechanisms that deal with low levels of schooling and precarious access to the labour market need to be addressed (Schneider 2015; Garcia et al. 2016).

Access to basic education is universal in Brazil, and was achieved in the mid-2000s. However, low levels of schooling, an outcome of the “atypical” development of the Brazilian educational system, are a major obstacle for many beneficiaries of the Bolsa Família Programme as they face difficulties in gaining access to educational programmes.8 For instance, to be included in policies such as PRONATEC (National Programme for Access to Technical Education and Employment), beneficiaries must have a certain level of educational attainment; but the educational levels of beneficiaries are too low to allow them to enrol in such courses and subsequently enter the labour market.

Further, data indicate that even when beneficiaries are able to enter the labour market, it is often in a precarious way, through informal and/or temporary jobs that have no guarantee of continuity though they might be important sources of household income. These workers often risk losing their incomes, either due to termination of employment or because of health-related problems as the informal labour market does not provide any social protection (Oliveira 2001).

A further aspect of policies on inclusion relates to schemes designed for populations in rural areas, which have the worst performance on indicators of poverty. The components of the BsM Plan, for example, do not address certain sections of the population, especially rural beneficiaries of the Bolsa Família Programme. Rural beneficiaries depend more on the Programme than their urban counterparts, as they do not have access to the labour market or to productive investments that could strengthen their assets (land, technology, etc.).

In many cases, cash transfers are the main source of income of beneficiary families in urban as well as rural areas, giving a strategic character to the Programme. The allowance was incorporated into the household budget, either for purchasing basic items or for productive investments (Schneider 2015). However, this is a sign of vulnerability that needs to be addressed.

At present, important changes are underway in these policies and actions. Soon after the impeachment of the President of the Republic, the Ministry of Agrarian Development was dissolved and replaced by a Department under the Ministry of Social and Agrarian Development. The primary responsibility of the dissolved ministry was to provide funds to small farmers to fund operational costs and investments, and therefore its dissolution raises concerns about the continuity of existing rural development policies and programmes, especially those that targeted poor farmers. Although it is too early to predict a course of action for the future, the possible discontinuance of programmes aimed at inclusion is significant, and could mark a return to the income transfer model as a more conventional tool to tackle poverty.9

Conclusions

Brazil gained international prominence in the first decade of the 2000s for its achievements in economic and social development. This was a result of state policy that supported development and the upward social mobility of the poorest strata of the population. Public policies played a central role in the process of development and in addressing social inequalities.

In this context, policies that promote welfare and social protection gained prominence, instead of a more philanthropic approach that focused solely on social inclusion. Apart from income distribution, social policies also guaranteed access to basic services such as, among other things, healthcare, education, electricity, and housing.

Thus, the first decade of the twenty-first century saw a substantial reduction of poverty and extreme poverty in Brazil, a significant increase in food security, greater access to state services such as healthcare and education, and improvements in the quality of life of the population through an increase in purchasing power, an increase in income among the poorest sections, and a reduction of social inequalities. The development process in Brazil had previously been linked solely to economic growth. This underwent a change to include an enhancement in the capabilities of and opportunities for disadvantaged sections, with a special emphasis on access to education. The results of this period of social inclusion will be visible in the years ahead.

Moreover, while social policies have fulfilled their primary objective, i.e. overcoming hunger and extreme poverty by expanding the opportunities made available to poorer sections of the population, they have also brought about positive changes in the process of development. These effects were more apparent in the rural areas of the country, where poverty reduction and upward social mobility became proportionally more significant. This can be attributed to the economic resources transferred to the beneficiaries of social programmes and the indirect impact of the transfers as represented by positive changes in rural economies.

Empirical studies have corroborated what researchers of public policies and development have already claimed: that social protection and development need to be addressed together, with the former serving as a basis for the latter. Given the positive results of the first phase of social development policies in Brazil, during which historical problems such as poverty and inequality were addressed, it is time now to take the next step and consolidate these results to help Brazil advance towards further development.

However, a new crisis has arrived and, with it, the appetite of the “owners of power”10 has intensified, as a spectre that surrounds the present and threatens the advancements that have been achieved.

Acknowledgements: The authors are grateful for financial support from the MDS/CNPq as part of the Call for Proposals MCTI-CNPq/MDS-SAGI No. 24/2013 – Social Development by the Brazilian National Council for Scientific and Technological Development – CNPQ, for developing the research behind this article. The Project was supported by the Department of Information Management and Assessment, Ministry of Social Development, Brazil.

Notes

1 For a brief overview, see Swaminathan (2012).

2 The income criterion for class segmentation in Brazil is an inadequate one (Souza 2006). It has been used here to provide readers with an idea of Brazilian society. The income range that defines class C was set, in the year of the referred publication, between R$ 1,276 and R$ 5,104. This amounts to US$ 391.41 and US$ 1,565.64, at the current exchange rate.

3 Grisa and Schneider (2015) make a comprehensive assessment of rural development policies implemented in Brazil since the mid-1990s. According to the authors, the outcomes of these policies were a combined effect of factors related to the interaction between state action, public policies, and civil society.

4 According to Brazilian labour legislation, family farmers, sharecroppers, and peasants above the age of 55 years for women and 60 years for men, are entitled to retirement as special insured persons and are exempted from the contribution time that is required of urban workers.

5 The Brazilian Food Insecurity Scale (Escala Brasileira de Insegurança Alimentar, or EBIA) is an index defined by the IBGE and measured by the Continuous National Household Sample Survey (PNAD). It comprises food security; slight food insecurity, moderate food insecurity, and severe food insecurity.

6 CadÚnico (Unified Register for Social Programmes) collects data to identify low-income families in the country, in order to provide them access to social programmes run by the Federal Government. Families with a monthly income of up to half the minimum wage (approximately US$ 145) per person are registered in it.

7 Data available with the IBGE (http://www.ibge.gov.br/estadosat/).

8 The development of the Brazilian educational system is said to be atypical as compared to that of other industrialised countries as the pattern of growth of enrolment at various stages is inverted. While usually, the growth within a particular level of education occurs when the level immediately below it is saturated, the reverse is true for Brazil, where higher levels of education showed faster growth rates without a corresponding saturation in enrolment at the primary stage. This pattern serves the interests of the elite. Ribeiro (2007), drawing from a study by Castro, notes that average enrolment growth rates in Brazil in the 1970s were 30.9 per cent for postgraduate studies, 11.6 per cent for higher education, 11.4 per cent for secondary school, and 3.6 per cent for elementary school. Similarly, in the period between 1950 and 1970, less than 70 per cent of children attended elementary school and only 10 per cent attended secondary school.

9 President Dilma Roussef was removed from office on May 12, 2016 by impeachment by the National Congress. The decision came into effect on August 31, 2016, following which Vice-President Michel Temer assumed the office of President. As this is a very recent development (at the time of writing this paper) and there is an absence of reliable data, this period has not been included in the present analysis. A recent announcement has said that the Bolsa Família Programme will continue, with the allowances being readjusted by 12.5 per cent. The process of reformulating the programme and altering its reach has started. Following the first review, 1.13 million beneficiaries were partially or completely excluded, representing just over 8 per cent of total beneficiaries. For further information on the political context that led to the impeachment, see Anderson (2016), Singer (2015b), and Saad-Filho (2016).

10 The term is from Faoro (1987).

References

| Amann, E., and Barrientos, A. (2015), “Is There a New Brazilian Development Model?” Policy in Focus, vol. 12, no. 3, International Policy Centre for Inclusive Growth and United Nations Development Programme. | |

| Anderson, P. (2016), “Crisis in Brazil,” London Review of Books, April 21. | |

| Aquino, J. R., and Bastos, F. (2015), “Dez Anos do Programa AGROAMIGO na Região Nordeste: Evolução, Resultados e Limites Para o Fortalecimento da Agricultura Familiar,” Revista Econômica do Nordeste (Portuguese), vol. 46, special supplement, pp. 139–60, July. | |

| Aquino, J. R., and Schneider, S. O. (2015), “Pronaf e o Desenvolvimento Rural Brasileiro: Avanços, Contradições e Desafios Para o Futuro,” in Catia Grisa, and Sergio Schneider (eds.), Políticas Públicas de Desenvolvimento Rural (Portuguese), 1st edition, UFRGS, Porto Alegre, pp. 53–81. | |

| Barufi, A. M. B. (2012), “Onde Estamos, Para Onde Vamos? Mobilidade Social no Brasil na Última Década e Perspectivas Para os Próximos Anos,” Conjuntura Macroeconômica Semanal (Portuguese), Departamento de Pesquisas e Estudos Econômicos, Bradesco, April 20. | |

| Bortoletto, A. (2013), Impactos do Programa Bolsa Família Sobre a Aquisição de Alimentos em Famílias Brasileiras de Baixa Renda (Portuguese), Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Nutrition and Public Health, Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo. | |

| Brauw, A., Gilligan, D. O., Hoddinott, J., and Roy, S. (2015), “The Impact of Bolsa Família on Schooling,” World Development, vol. 70, pp. 303–16. | |

| Câmara Interministerial De Segurança Alimentar E Nutricional (CAISAN) (2014), Balanço das Ações do Plano Nacional de Segurança Alimentar e Nutricional - Plansan 2012/2015 (Portuguese), MDS, Brasília. | |

| Campello, T., and Neri, M. C. (eds.) (2013), Programa Bolsa Família: Uma Década de Inclusão e Cidadania (Portuguese), IPEA, Brasília. | |

| Campello, T., Falcão, T., and Costa, P. V. (2014), O Brasil Sem Miséria (Portuguese), MDS, Brasília. | |

| Campello, T. A. (2017), “Experiência Brasileira na Superação da Extrema Pobreza,” Seminário Internacional WWP – Um Mundo sem Pobreza (Portuguese), Brasília. | |

| Castilho e Silva, C. B. (2014), O Programa Bolsa Família no Meio Rural: Um Caminho ao Desenvolvimento no Rio Grande do Sul? (Portuguese) Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Rural Development, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul, Rio Grande do Sul. | |

| Castro, J. A. (2011), “Gastos com a Política Social: Alavanca Para o Crescimento com Distribuição de Renda,” Comunicados do IPEA (Portuguese), no. 75, February 3. | |

| Castro, J. (1984), Geografia da Fome (O Dilema Brasileiro: Pão ou Aço) (Portuguese), Edição Antares, Rio de Janeiro. | |

| Devereux, S., and Sabates-Wheeler, R. (2004), “Transformative Social Protection,” IDS Working Paper 232, Institute of Development Studies, Brighton. | |

| Duarte, G. B., Sampaio, B., and Sampaio, Y. (2009), “Programa Bolsa Família: Impacto das Transferências Sobre os Gastos com Alimentos em Famílias Rurais,” Revista de Economia e Sociologia Rural (Portuguese), vol. 47, no. 4, October/December, pp. 903–18. | |

| Faoro, R. (1987), Os Donos do Poder: Formação do Patronato Político Brasileiro (Portuguese), 7th edition, Editora Globo, Rio de Janeiro. | |

| Favero, C. A. (2011), “Políticas Públicas e Reestruturação de Redes de Sociabilidades na Agricultura Familiar,” Caderno CRH (Portuguese), vol. 24, no. 63, pp. 609–26. | |

| Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) (2015), “The State of Food and Agriculture: Social Protection and Agriculture: Breaking the Cycle of Rural Poverty,” FAO, Rome. | |

| Food and Agriculture Organisation, International Fund for Agricultural Development, and World Food Programme (FAO, IFAD, and WFP) (2015a), The State of Food Insecurity in the World, 2015: Meeting the 2015 International Hunger Targets: Taking Stock of Uneven Progress, FAO, Rome. | |

| Food and Agriculture Organisation, International Fund for Agricultural Development, and World Food Programme (FAO, IFAD, and WFP) (2015b), Achieving Zero Hunger: The Critical Role of Investments in Social Protection and Agriculture, FAO, Rome. | |

| França, C. G., Marques, V. P. M. A., and Del Grossi, M. E. (2016), Superação da Fome e da Pobreza Rural (Portuguese), Iniciativas Brasileiras-FAO, Brasília. | |

| Garcia, F., Helfand, S., and Souza, A. P. (2016), “Transferencias Monetarias Condicionadas y Políticas de Desarrollo Rural en Brasil: Posibles Sinergias Entre Bolsa Familia y el Pronaf,” in J. H. Maldonado (ed.), Protección, Producción, Promoción: Explorando Sinergias Entre Protección Social y Fomento Productivo Rural en América Latina (Portuguese), Universidad de los Andes, Facultad de Economía, CEDE/FIDA, Bogotá, pp. 69–115. | |

| Grisa, C., and Schneider, S. (eds.) (2015), Políticas Públicas de Desenvolvimento Rural (Portuguese), UFRGS, Porto Alegre. | |

| Hall, A., and Midgley, J. (2004), Social Policy for Development, Sage Publications, London. | |

| Hall, A. (2006), “From Fome Zero to Bolsa Família: Social Policies and Poverty Alleviation Under Lula,” Journal of Latin American Studies, vol. 38, pp. 689–709. | |

| Hall, A. (2008), “Brazil’s Bolsa Família: A Double-edged Sword?” Development and Change, vol. 39, no. 5, pp. 799–822. | |

| Hall, A. (2012), “The Last Shall Be First: Political Dimensions of Conditional Cash Transfers in Brazil,” Journal of Policy Practice, vol. 11, nos. 1-2, pp. 25–41. | |

| High Level Panel of Experts (HLPE) (2012), “Social Protection for Food Security,” Report by the High Level Panel of Experts on Food Security and Nutrition of the Committee on World Food Security, Rome. | |

| Institute for Applied Economic Research (IPEA) (2012), “A Década Inclusiva 2001-2011: Desigualdade, Pobreza e Políticas de Renda,” Comunicados do IPEA (Portuguese), no. 155, Brasília. | |

| Institute for Applied Economic Research (IPEA) (2015), Políticas Sociais: Acompanhamento e Análise (Portuguese), vol. 1, no. 23, IPEA, Brasília. | |

| Institute for Applied Economic Research Data (IPEADATA) (2014), Dados do Programa Bolsa Família (Portuguese), available at http://www.ipeadata.gov.br/, viewed on Jan 18, 2014. | |

| Kerstenetzky, C. L. (2009), “Welfare State e Desenvolvimento,” Dados – Revista de Ciências Sociais (Portuguese), vol. 52, no. 1, pp. 53–83. | |

| Lencione, S. (2008), “Concentração e Centralização das Atividades Urbanas: Uma Perspectiva Multiescalar: Reflexões a Partir do Caso de São Paulo,” Revista de Geografia Norte Grande (Portuguese), no. 39, May, pp. 7–20. | |

| Lavergne, R. M., and Beserra, B. (2016), “The Bolsa Família Programme: Replacing Politics with Biopolitics,” Latin American Perspectives, issue 207, vol. 43, no. 2, March, pp. 96–115. | |

| Maia Gomes, G. (2001), Velhas Secas em Novos Sertões: Continuidade e Mudanças na Economia do Semiárido e dos Cerrados Nordestinos (Portuguese), IPEA, Brasília. | |

| MDS/CadÚnico/TABCAD (2016), Tabulador com Duas Variáveis (Famílias e Pessoas) (Portuguese), available at http://aplicacoes.mds.gov.br/sagi/cecad/tabulador_tabcad.php, viewed on March 4, 2015. | |

| Mello, R., and Duarte, G. (2010), “Impacto do Programa Bolsa Família Sobre a Frequência Escolar: O Caso da Agricultura Familiar no Nordeste do Brasil,” Revista de Economia e Sociologia Rural (Portuguese), vol. 48, no. 3, July-September. | |

| Neri, M. (ed.) (2010), Nova Classe Média: O Lado Brilhante dos Pobres (Portuguese), FGV-CPS, Rio de Janeiro. | |

| Neri, M. (2012), Superação da Pobreza e a Nova Classe Média no Campo (Portuguese), MDA-NEAD, Brasília. | |

| Neri, M. (2013), “Duas Décadas de Desigualdade e Pobreza no Brasil Medidas Pela,” Comunicados do IPEA (Portuguese), IPEA, PNAD-IBGE, no. 159, Oct 1. | |

| Nunes, J., and Mariano, J. (2015), “Efeitos dos Programas de Transferência de Renda Sobre a Oferta de Trabalho Não Agrícola na Área Rural da Região Nordeste (Portuguese),” RESR, vol. 53, no. 1, January-March, pp. 71–90. | |

| Oliveira, F. (2001), Aproximações ao Enigma: O Que Quer Dizer Desenvolvimento Local? Programa Gestão Pública e Cidadania/EAESP/FGV (Portuguese), Pólis, São Paulo. | |

| Osório, R. G. (2011), Perfil da Pobreza no Brasil e Sua Evolução no Período 2004-2009, Texto para discussão 1647 (Portuguese), IPEA, Brasília, August. | |

| Paiva, L. H., Soares, F. V., Cireno, F., Viana, I. A. V., and Duran, A. C. (2016), “The Effects of Conditionality Monitoring on Educational Outcomes: Evidence from Brazil’s Bolsa Família Programme,” International Policy Centre for Inclusive Growth, United Nations Development Programme, Working Paper No. 144, June. | |

| Parsons, K. H. S. (2015), Reaching Out to the Persistently Poor in Rural Areas: An Analysis of Brazil’s Bolsa Família Conditional Cash Transfer Programme, Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, London School of Economics, London. | |

| Rasella, D., Aquino, R., Santos, C. A. T., Sousa, R. P., and Barreto, M. L. (2013), “Effect of a Conditional Cash Transfer Programme on Childhood Mortality: A Nationwide Analysis of Brazilian Municipalities,” The Lancet, vol. 382, no. 9886, pp. 57–64, July. | |

| Ribeiro, C. A. C. (2007), Estrutura de Classe e Mobilidade Social no Brasil (Portuguese), Bauru-SP, Edusc-Anpocs. | |

| Saad-Filho, A. (2016), “Watch Out for Judicial Coup in Brazil,” Monthly Review, March 23, available at http://mrzine.monthlyreview.org/2016/sf230316.html, viewed on January 8, 2017. | |

| Schneider, S. (2015), A Articulação de Políticas Para a Superação da Pobreza Rural: Um Estudo Comparativo das Interfaces Entre o Programa Bolsa Família e as Políticas de Inclusão Produtiva nas Regiões Nordeste e Sul do Brasil (Portuguese), Research Report, RS: PGDR/UFRGS/MDS, Porto Alegre. | |

| Sen, A. (2000), Desenvolvimento como Liberdade (Portuguese), Cia das Letras, São Paulo. | |

| Silveira, F. G. (2016), Políticas Públicas para o Desenvolvimento Rural e de Combate à Pobreza no Campo (Portuguese), IPC-IG/PNUD, Brasília. | |

| Singer, A. (2015a), “Quatro Notas Sobre as Classes Sociais nos dez Anos do Lulismo (Portuguese),” Psicologia USP, vol. 26, no.1, pp. 7–14. | |

| Singer, A (2015b), “Cutucando Onças com Varas Curtas,” Novos Estudos (Portuguese), vol. 102, July. | |

| Souza, J. (ed.) (2006), A Invisibilidade da Desigualdade Brasileira (Portuguese), Editora UFMG, Belo Horizonte. | |

| Souza, J. (2009), A Ralé Brasileira: Quem é e Como Vive (Portuguese), Editora UFMG, Belo Horizonte. | |

| Souza, J. (2010), Os Batalhadores Brasileiros: Nova Classe Média ou Nova Classe Trabalhadora? (Portuguese) Editora UFMG, Belo Horizonte. | |

| Souza, S. C. M., Almeida Filho, N., and Neder, H. D. (2015), “Food Security in Brazil: An Analysis of the Effects of the Bolsa Familia Programme,” Review of Agrarian Studies, vol. 5, no. 2, available at http://ras.org.in/food_security_in_brazil_an_analysis_of_the_effects_of_the_bolsa_familia_programme, viewed on May 25, 2017. | |

| Swaminathan, M. (2012), “Food Policy and Public Action in Brazil,” Review of Agrarian Studies, vol. 2, no. 2, available at http://ras.org.in/food_policy_and_public_action_in_brazil, viewed on May 25, 2017. | |

| Tirivayi, N., Knowles, M., and Davis, B. (2013), “The Interaction Between Social Protection and Agriculture: A Review of Evidence,” available at http://www.fao.org/3/a-i3563e.pdf, viewed on May 25, 2017. | |

| Vieira, K. M. (2016), “Gerenciamento Financeiro dos Benefícios Advindos do Programa Bolsa Família: Uma Análise da Alfabetização Financeira, do Endividamento e Bem-Estar Financeiro,” in P. Januzzi, and P. Montagner (eds.), Síntese das Pesquisas de Avaliação de Programas Sociais do MDS 2015–2016: Caderno de Estudos Desenvolvimento Social em Debate (Portuguese), MDS, Brasília. |