ARCHIVE

Vol. 2, No. 1

JANUARY-JUNE, 2012

Research Articles

Research Notes and Statistics

Special Essay

Field Reports

Book Reviews

Addressing the Global Food Crisis:

Causes, Implications, and Policy Options1

C. P. Chandrasekhar* and Jayati Ghosh†

*Professor, Centre for Economic Studies and Planning, School of Social Sciences, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi.

†Professor, Centre for Economic Studies and Planning, School of Social Sciences, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi, jayatijnu@gmail.com.

Abstract: This paper considers some of the recent trends in global food prices and their possible links to financial speculation, as well as the policy measures required to contain speculation. Recent trends in the price movements of major food commodities in international trade are briefly described, followed by a consideration of the financial deregulation in the USA in 2000 that enabled greater involvement of financial agents in commodity futures markets, as well as of the pattern and implications of such involvement in the period after 2006. Finally, there is a discussion of some of the current moves for regulation in this area, as well as other proposals and strategies for ensuring greater stability in global food markets.

Keywords: food crisis, food prices, commodity futures markets, financial regulation.

Introduction and Background

The link between significantly increased price volatility in global food markets and financial activity in commodity futures markets is now much more widely recognised than before. This means that the argument for effective financial regulation to curb financial activity and the associated volatility in primary commodity markets is now more compelling than ever, in the context of a renewed increase in food prices. This paper considers some of the recent trends in global food prices and their possible links to financial speculation, as well as the moves towards regulation of such activity in both the United States and Europe.

In the opening section of the paper, recent trends in price movements of major food commodities in international trade are briefly described. The second section is devoted to a consideration of the financial deregulation in the USA in 2000, which enabled greater involvement of financial agents in commodity futures markets, as well as the pattern and implications of such involvement in the period after 2006. The third section contains a discussion of some current moves for regulation in this area, as well as other proposals and strategies for ensuring greater stability in global food markets.

It is clear that we are now back in another phase of sharply rising global food prices, which are wreaking further devastation on populations in developing countries that have already been ravaged for several years by rising prices and falling employment opportunities. In December 2010 the food price index of the Food and Agricultural Organisation of the United Nations (FAO) surpassed its previous peak of June 2008, which is still thought of as the extreme peak of the world food crisis. Since then it has increased in some periods or generally remained around this very high level.2

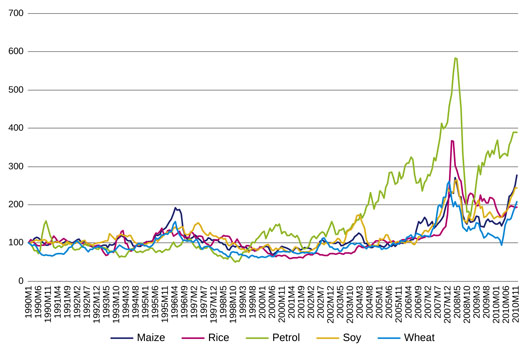

In the more recent period, some of the biggest increases have been in the prices of sugar and edible oils. The US import price of sugar doubled over the second half of 2010. Traded prices of edible oils like soyabean oil and palm oil increased by an average of 50 per cent over the same period. But even prices of staples have shown sharp increases, with the biggest increase being in wheat prices, which went up by 95 per cent between June and December 2010. Rice prices, in comparison, have been relatively stable in global trade over 2011 and early 2012, but the FAO reports that domestic prices in major rice producing and consuming countries, especially in Asia, have continued to increase and by early 2012 were at their highest levels ever.

Source: IMF online database on commodity prices.

It is now more widely recognised that the global food crisis cannot be treated as discrete and separate from the global financial crisis. On the contrary, the two are intimately connected, particularly through the impact of financial speculation on world trade prices of food.

This is not to deny the role of other real economy factors in affecting the global food situation. While demand-supply imbalances have been touted as a reason, this is largely unjustified given that there has been hardly any change in the world demand for food over 2009-11. A recent report of a High Level Panel of Experts on Commodity Price Volatility and Food Security set up by the FAO noted that the growth rate of total cereal consumption was considerably slower in the decade of the 2000s than it was in the 1960s and 1970s, and only around the same as it was in the 1980s. It did increase relative to the 1990s, but not by very much. And, contrary to the general perception, feed consumption of livestock increased more slowly than direct (or non-feed) consumption. Even the apparent acceleration of feed use in the last decade was essentially because of the recovery of feed use in the former Soviet Union after the 1990s. So, despite the booming demand for meat in fast-growing Asia, the growth of feed consumption in the rest of the world outside the former Soviet Union has not been accelerating but slowing down (see FAO 2011).

In particular, the claim that foodgrain prices have soared because of greater demand for food from China and India as their GDP increases is completely invalid, since both aggregate and per capita consumption of grain have actually fallen in both countries. FAO food balance sheets show that both direct and indirect demand for grain in China and India barely increased between 2000 and 2007, and that cereal imports were lower.3 Why this has been happening and why economic growth has not translated into more aggregate demand for grain are fascinating questions on their own that deserve separate study. It is likely that the worsening income distribution in both countries has something to do with it, so that increased demand from high-income groups is counterbalanced by reduced demand from poorer sections - but this needs to be explored further. The relevant point in this context is that it is not increased demand from China and India that is driving up grain prices.

This does not mean that there are no other demand forces at work. The biofuel boom has had a major impact on the evolution of world food demand for cereals and vegetable oils. According to the FAO's High Level Panel of Experts report,

there is a real acceleration of non-feed uses boosted by biofuel development. Excluding use for biofuel, the growth rate for non-feed use is stable compared with the 1990s and markedly inferior to its historical performance. Without biofuel, the growth rate of world cereal consumption is equal to 1.3 per cent compared with 1.8 per cent for biofuel. (FAO 2011, p. 32)

Supply factors have been - and are likely to continue to be - more significant. These include not just the short-run effects of the diversion of both acreage and foodcrop output for biofuel production, but more medium-term factors such as rising costs of inputs, falling productivity because of soil depletion, inadequate public investment in agricultural research and extension, and the impact of climate changes that have affected harvests in different ways. Another important element in determining food prices is oil prices: since oil (or fuel) enters directly and indirectly into the production of inputs for cultivation, as well as irrigation and transport costs, its price tends to have a strong correlation with food prices. Curbing volatility in oil prices would thus help stabilise food prices to some extent.

Despite all this, it is clear that the recent volatility in world trade prices of important food items cannot be explained simply in terms of real demand and supply factors. The extent of price variation in such a short time already suggests that such movements could not have been created by supply and demand, especially as in world trade the effects of seasonality in a particular region are countered by supplies from other regions. In any case, FAO data show very clearly that there was scarcely any change in global supply and utilisation over 2007-10, and that, if anything, output changes were more than sufficient to meet changes in utilisation in the period of rising prices, while supply did not greatly outstrip demand in the period of falling prices (see FAO 2009, 2010; and Ghosh 2010). Instead, it can be plausibly argued that financial speculation - specifically, investor activity in unregulated (over-the-counter) commodity futures - was the major factor behind the sharp price rise of many primary commodities, including agricultural items (UNCTAD 2009; IATP 2008, 2009; Wahl 2009; Robles, Torrero, and von Braun 2009; World Development Movement 2010; UN Special Rapporteur 2010; Gilbert 2010). Even recent research from the World Bank recognises the role played by the "financialisation of commodities" in price surges and declines, and notes that price variability has overwhelmed price trends for important commodities (Bafis and Haniotis 2010).

The Role of Corporate Retail

It is important to consider the impact of large corporate retail, especially multinational retail chains, on the food systems of developing countries. Proponents of such corporate retailing make several claims: that they "modernise" distribution by bringing in more efficient techniques that also reduce wastage and the costs of storage and distribution; that they provide more choice to consumers; that they lower distribution margins and provide goods more cheaply; that they are better for direct producers, such as farmers, because they reduce the number of intermediaries in the distribution chain; and that they provide more employment opportunities.

All of these claims are somewhat suspect, however, and several are completely false. This is particularly so in the case of employment generation: experience across the world makes it incontrovertible that large retail companies displace many more jobs of petty traders than the jobs they create in the form of employees. This has been true of all the countries that have opened up to such companies, from Turkey (in the 1990s) to South Africa. Large retail chains typically use much more capital-intensive techniques, and have much more floor space, goods, and sales turnover per worker. One estimate suggests that for every job Walmart (the largest global retail chain) creates in India, it would displace 17 to 18 local small traders and their employees. In a country like India this is of major significance, since around 44 million people are now involved in retail trade (26 million in urban areas), and they are overwhelmingly in small shops or self-employed. Since other organised activities in India create hardly any additional net employment, and overall there has been a severe slowdown in job growth in the period 2004-05 to 2009-10, this is a matter that simply cannot be ignored.

The argument that large retail benefits direct producers like farmers is also contestable. The greater market power of these large intermediaries has been associated in many countries with higher marketing margins and the exploitation of small producers. This is true even of the developed countries, where the more organised and vocal farmers have protested against giant retailers squeezing the prices paid to farmers for their products, in some instances forcing them to sell at below-cost prices. The European Parliament in fact adopted a declaration in February 2008 which stated that

throughout the EU, retailing is increasingly dominated by a small number of supermarket chains...evidence from across the EU suggests large supermarkets are abusing their buying power to force down prices paid to suppliers (based both within and outside the EU) to unsustainable levels and impose unfair conditions upon them.

In the United States, marketing margins for major food items increased rapidly in the 1990s, a period when there was significant concentration of food retail.

The idea that cold storage and other facilities can only be developed by large, private corporates involved in retail food distribution is foolish: proactive public intervention can (and has, in several countries) ensure better cold storage and other facilities through various incentives and promotion of farmers' cooperatives. The argument is also made that corporate retail will encourage more corporate production, which in turn supposedly involves more efficient and less "wasteful" use of the products. But calculations of efficiency based only on marketed output miss the mark, because they do not include the varied uses of by-products by farmers. Biomass, for instance, is used extensively and scrupulously by most small cultivators, but industrial-style farming tends to negate it and does not even measure it. Biodiversity, use of biomass, and interdependence that create resilient and adaptive farming systems, are all threatened by a shift to more corporate control of agriculture.

There is another crucial implication that is all too often ignored in discussions of corporate retail. Corporate involvement in the process of food distribution creates changes in eating habits and farming patterns that result not just in unsustainable forms of production that are ecologically devastating, but also in unhealthy consumption choices. In the developed world, this has been effectively documented by books like Eric Schlosser's Fast Food Nation and Michael Pollan's The Omnivore's Dilemma.

In the Baltic countries, this has led to a striking breakdown of any real link between local production and the supply of food. The global supply chain has become the source of most food and the European market has become the destination of food production - all mediated by large chains that deal in buying from farmers (often through contract-farming arrangements that specify inputs and crops beforehand) and in food distribution down to retail outlets. Anecdotal evidence suggests that farmers have not gained from this even in a period of rising food prices, as they are powerless relative to the large traders who control the market. And consumers continue to complain about the rising prices of food, which the supposedly more "efficient" supermarkets have not prevented at all.

As affluent western markets reach saturation point, global food and drink firms have been seeking entry into developing country markets, often targeting poor families and changing food consumption habits. Such highly processed food and drink is also a major cause of increased incidence of lifestyle diseases such as obesity, diabetes, heart disease, and alcoholism, all of which have been rising rapidly in the developing world. The recent experience of South Africa is especially telling: diabetes rates are soaring; and around one-fourth of the country's schoolchildren are obese or overweight, as are 60 per cent of women and 31 per cent of men. Yet nearly 20 per cent of children aged one to nine have stunted growth, having suffered the kind of long-term malnutrition that leaves irreversible damage. And it has been found that obesity and malnutrition often occur in the same household.4

A recent report on the global food crisis produced by Timothy Wise and Sophia Murphy makes several interesting points about how the crisis is related to not just medium-term supply factors that reflect the effects of more open trade and the policy neglect of agriculture, but also to the biofuel subsidies that have diverted grain acreage and production, as well as the role of financial speculation in pushing up prices of food (Wise and Murphy 2012). The report also highlights a feature that is often ignored in policy discussion on the food crisis: market power in the food system.

Wise and Murphy note:

As agricultural, energy, and financial markets become more integrated on a global scale, the power of transnational firms within the global food system grows. This poses significant threats to global food security, despite the advanced production and communication systems these firms bring (ibid., p. 33).

Hence, the needed policy changes include policies that curb the market power of transnational companies in the food system. Unfortunately, there are very few such initiatives; instead, "the expanded interest in public-private partnerships and the continued commitment to the expansion of industrial agriculture lead in the opposite direction" (ibid.).

Another voice that has raised this issue in the international policy discussion is that of the UN Special Rapporteur on the Right to Food, Oliver de Schutter. In a Briefing Note on "Addressing concentration in food supply chains," he points out that

Disproportionate buyer power, which arises from excessive buyer concentration in food supply chains (among commodity buyers, food processors, and retailers), tends to depress prices that food producers at the bottom of those chains receive for their produce. This in turn means lower incomes for these producers, which may have an impact on their ability to invest for the future and climb up the value chain, and it may lead them to lower wages that they pay the workers that they employ. There is thus a direct link between the ability of competition regimes to address abuses of buyer power in supply chains, and the enjoyment of the right to adequate food.5

These forms of market power and their effects are elaborated in a paper by Aravind Ganesh on "The right to food and buyer power" (2011). Ganesh points out that excessive buyer power harms both ends of the food distribution chain: the (usually small) direct producers and the final consumers.

The extreme concentration in the middle of global supply chains is already a matter of major concern. Thus, for example, Ganesh notes that in only one example (that of the global coffee industry) in 2008, it was estimated by the World Bank that while there were around 25 million coffee growers and 500 million consumers, only four firms accounted for nearly half of the coffee roasting and trading industries. For tea, three companies controlled over 80 per cent of global distribution. In commodities as varied as grain, soyabean and other oilseeds, sugar and cocoa, a few large companies dominated global processing and distribution. In many cases, such as Nestle and Parmalat in the Brazilian dairy industry (where they now account for 53 per cent of processing), these companies have come to acquire their dominant market power by allegedly driving out farmers' cooperatives, which were effectively forced to sell their facilities to the large players.

Such concentration gives these large companies considerable power to set the terms, conditions, and prices for the produce they acquire from farmers. This can even deprive farmers of the ability to earn enough income to feed their households. Ganesh notes that

studies have shown that the practice of dominant UK groceries retailers, of passing on to Kenyan producers the cost of compliance with the retailers' private standards on hygiene, food safety and traceability, has resulted in the moving away of food production from small holders to large farms, many of which were owned by exporters, as well as the acquisition of exporters of their own production capacity. In short, farmers are being excluded from global grocery supply chains, thus severely damaging their incomes. (Ganesh 2011, p. 1196)

Ganesh cites several cases where the competition and anti-trust authorities in different countries have been forced to take on multinational firms for their collusive practices. In South Africa, a milk cartel had to be investigated for colluding to fix the purchase price of milk, and imposing contracts on small dairy farmers to supply their total milk production without retaining anything even for household consumption. Another investigation was launched into supermarkets denying small producers access to retail shelves as a result of buyer concentration.

Even in Asia, in countries like South Korea, Taiwan China, and Thailand, competition authorities have brought action against dominant multinational buyers such as Wal-Mart and Carrefour for various kinds of abusive conduct. These include strategies that adversely affect small producers in particular, such as refusal to receive products, unfair price reductions, unfair passing on of advertising fees to producers, and charging improper fees and unreasonable penalties for supply shortages. In all these cases fines had to be imposed on the multinational companies, but in the absence of strict guidelines and constant regulatory monitoring, it is likely that such behaviour will continue.

Financial Deregulation and Global Food Markets

Futures markets for food, oil, and other commodities have long been used by farmers and others to maintain stability in business operations and to plan for the future. Commercial traders would purchase food commodities from farmers for future delivery at a fixed price. This would relieve the farmers of any risks associated with future fluctuations in the prices of the food commodities they were growing. As with any insurance-type arrangement, the commercial traders would assume the farmers' risk for a fee. They would earn their fee no matter what happened to food prices over time. But the traders would also speculate that they could profit from changes in future market prices.

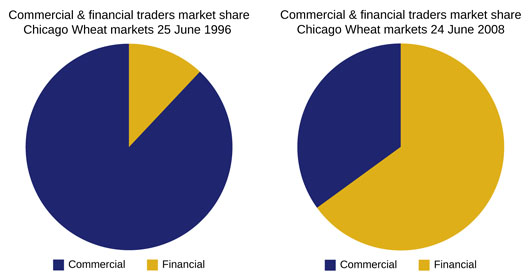

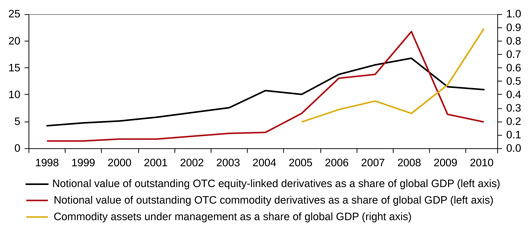

Financial deregulation in the early 2000s gave a major boost to the entry of new financial players into commodity exchanges. In the US, which has the greatest volume and turnover of both spot and future commodity trading, the significant regulatory transformation occurred in 2000. While commodity futures contracts existed before then, they were traded only on regulated exchanges under the control of the Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC), which required traders to disclose their holdings of each commodity and stick to specified position limits, so as to prevent market manipulation. Therefore commodity exchange was dominated by commercial players who used it for the reasons mentioned above, rather than for mainly speculative purposes. In 2000, the Commodity Futures Modernization Act effectively deregulated commodity trading in the United States, by exempting OTC (over-the-counter) commodity trading (outside of regulated exchanges) from CFTC oversight. Soon after this, several unregulated commodity exchanges opened. These allowed any and all investors, including hedge funds, pension funds, and investment banks, to trade commodity futures contracts without any position limits, disclosure requirements, or regulatory oversight. The value of such unregulated trading was as much as $9 trillion at the end of 2007, which was estimated to be more than twice the value of the commodity contracts on the regulated exchanges. According to the Bank for International Settlements, the value of outstanding amounts of OTC commodity-linked derivatives for commodities other than gold and precious metals increased from $5.85 trillion in June 2006 to $7.05 trillion in June 2007, and to as much as $12.39 trillion in June 2008 (BIS 2009). In addition, as Figure 2 indicates, even on the regulated exchanges there was a significant increase in the involvement of purely financial players as opposed to commercial entities.

Source: Better Markets submission to Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC) on position limits.

Unlike producers and consumers who use such markets for hedging purposes, financial firms and other speculators increasingly entered the market in order to profit from short-term changes in price. They were aided by the "swap-dealer loophole" in the 2000 legislation, which allowed traders to use swap agreements to take long-term positions in commodity indexes. There was a consequent emergence of commodity index funds that were essentially "index traders" who focus on returns from changes in the index of a commodity, by periodically rolling over commodity futures contracts prior to their maturity date and reinvesting the proceeds in new contracts. Such commodity funds dealt only in forward positions with no physical ownership of the commodities involved. This further aggravated the treatment of these markets as vehicles for a diversified portfolio of commodities (including not only food, but also raw materials and energy) as an asset class, rather than as mechanisms for managing the risk of actual producers and consumers.

Overall, the number of derivatives contracts increased more than six-fold between 2002 and mid-2008, as these investment vehicles became a safe haven from the subprime crisis and financial meltdown. It has been estimated that index fund purchases from 2003 to 2007 already were higher than the futures market purchases of physical hedgers and traditional speculators combined, and then doubled in the first half of 2008.

The trend movements in food prices underwent a structural shift at the same time as index traders began dominating the commodities futures markets for food. Thus, between 1975-76 and 2000-01, world food prices declined by 53 per cent in real US dollar terms. However, since 2000-01, this trend has been reversed. Between January 2002 and June 2008, the global food index rose by 133 per cent. The rapid price increases were led by grains in 2005, despite a record global crop yield in 2004-05. Between January 2005 and June 2008, maize prices tripled, wheat rose by 127 per cent, and rice rose 170 per cent. A 2009 study by the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) reports that "the price boom between 2002 and mid-2008 was the most pronounced in several decades - in magnitude, duration and depth" (UNCTAD 2009, p. 72).

After the dramatic rise - especially in the period June 2007 to June 2008, when the global food price index nearly doubled - global commodity prices then collapsed almost equally sharply, such that by December 2008 they were back to their levels of the previous year. Obviously, such large swings in commodity (and especially food) prices cannot be explained by changes in real demand and supply, especially as FAO data indicate that aggregate global supply and utilisation changed very little over this period.

Food prices started rising again in early 2009, though at a slower rate. However, in the second half of 2010, they once again rose rapidly. By December 2010, the index was 136 per cent higher than in January 2002. In the second half of 2010, food prices nearly doubled in the case of wheat and increased by more than 60 per cent in the case of maize. Similar trends were evident in the petroleum market, driving oil prices up to around $100 a barrel. Since fuel is a universal intermediate, and enters into cultivation costs (through the price of fertilizer, and the costs of diesel for pump-sets and tractors) and transport costs for agricultural produce, higher oil prices also fed into higher food prices, creating another source of price spiral. It is likely that the movement of the index funds has also been driven by the price of oil, itself a highly speculative market with some 70 per cent of futures investments coming from non-commercial speculators. This possibility is indeed embedded in the structure of global oil markets, as noted in Roncaglia (2003). Under such institutionalised structures, the price of oil drives the movement of the index funds, and pushes up the prices of food and other agricultural commodities, regardless of the real supply and demand of such commodities.

Similarly, it is likely that a combination of panic buying and speculative financial activity is once again playing a role in driving world food prices up well beyond anything that is warranted by real quantity movements. Data on financial activity in commodity futures markets from the US Commodity Futures Trading Commission suggest that until the end of December 2010, the net long positions of index investors had increased dramatically in commodities like wheat and corn. This explains, to some extent, the dramatic increase (doubling) in the price of wheat in the period June-December 2010, a period when actual global wheat production slightly increased and demand (as expressed in the FAO's measure of "utilisation") was roughly unchanged.

Source: Quoted in UNCTAD (2011).

Impact on Developing Countries

Global price volatility has had very adverse effects on both cultivators and consumers of food. It is often argued that rising food prices at least benefit farmers, but this is often not the case as marketing intermediaries tend to capture the benefits for themselves. This tendency has been accentuated over the past two decades with growing concentration in agribusiness. In any case, with price changes of such short duration, cultivators are unlikely to gain. One major reason for this is that such price changes send out confusing, misleading, and often completely wrong price signals to farmers, causing over-sowing in some phases and under-cultivation in others. Many farmers in the developing world have found that the financial viability of cultivation has actually decreased in this period, because input prices have risen and output prices have been so volatile that the benefit has not accrued to direct producers. In addition, this price volatility has been bad news for most consumers, especially in the developing countries.

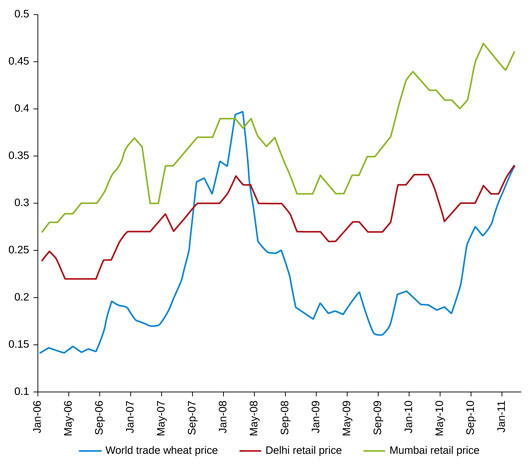

It is true that high global prices need not (and should not) translate directly into prices faced by consumers in poor developing countries. Certainly, given the much lower per capita incomes in such countries and therefore lower purchasing power of the people, it should be expected that there would be some public mediation of the relationship between global prices and domestic food prices. This is all the more desirable, if not essential, in periods of high price volatility in global trade, such as has been marked in 2007-11. Otherwise, poor consumers in the developing world, in countries where basic foodgrains still account for around 40-50 per cent of the consumption basket of the poor, would be sharply affected by such price movements.

As it happens, the period of dramatic increases in price volatility in global markets was also one in which there was very high transmission of international price changes to domestic prices in many developing countries. This is evident from a quick perusal of retail price changes in the wheat and rice markets in some developing countries. The pass-through of global prices was extremely high in developing countries in the phase of rising prices, in that domestic food prices tended to rise as global prices increased, even if not to the same extent (Chandrasekhar and Ghosh 2011). However, the reverse tendency has not been evident in the subsequent phase as global trade prices have fallen. In late 2010, around 20 countries faced food emergencies and another 25 or so were likely to have moderate to severe food crises (FAO 2010). Even in countries that are not described as facing food emergency, the problem is severe for large parts of the population.

Consider India, a country which currently has the largest number of hungry people in the world and very poor nutrition indicators in general, despite nearly two decades of rapid income growth. Figure 4 shows the behaviour of retail wheat prices in two major cities - Delhi and Mumbai - in relation to the global trade price of wheat (relating to US wheat in the Chicago Board of Trade).

Source: FAO GIEWS, viewed on March 19, 2011.

Two important features are immediately evident from this chart: first, the substantial variation in retail prices across the two Indian cities (which would be reinforced by other data showing the variation in retail prices across other towns and cities), which suggests that there is still an absence of a national market for essential food items, even those that can be transported and stored easily; secondly, the degree to which price changes have tracked international prices.

Many analysts have argued that the Indian foodgrain market is insulated from the international market because of the system of domestic public food procurement and distribution. Indeed, until the early part of the 2000s, this was generally true. However, since then, the opening of agricultural items to international trade without quantitative restrictions has clearly allowed for a greater impact of global prices on domestic prices.

Further, the public distribution system itself has been increasingly run down in the past two decades. It has been further complicated recently by the insistence of the central government on raising procurement prices and procuring more, but not distributing the increased procurement to the States, to allow them to provide wheat to the defined "non-poor" population in a manner that would restrain prices. Instead, the focus has been on building central stocks, which has turned out to be somewhat counterproductive because of the lack of adequate storage facilities. As a result, India's retail wheat prices have been higher than global prices in both these urban centres (Delhi and Mumbai). They rose by about 30 per cent in the year up to October 2010 as global prices also increased.

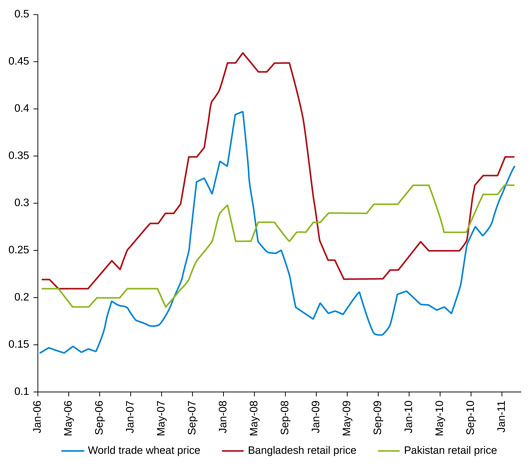

Figure 5 describes the behaviour of wheat retail prices in two other South Asian countries - one a domestic producer and occasional exporter of wheat (Pakistan), and the other an importer where wheat is still important in fulfilling dietary needs (Bangladesh).

Source: FAO GIEWS, viewed on March 19, 2011.

Retail prices in Bangladesh have closely tracked global trade prices, always remaining higher. This in itself is significant, given the low purchasing power of most Bangladeshi consumers. It indicates that there is little to no mediation between import prices and prices faced by consumers in the country, and that the latter are subject to the fierce fluctuations and rising tendencies that characterise the global market.

It is surprising that the same is broadly true of Pakistan (the retail price here relates to Lahore city). What is of interest in this case is that while periods of rising prices globally appear to be marked by rapid transmission to Lahore retail prices, the periods of global price reduction show no such tendency. In fact, Lahore retail prices kept rising even as global prices came down, such that even after the latest surge in global prices, they are still at around the same level as the Pakistan retail price.

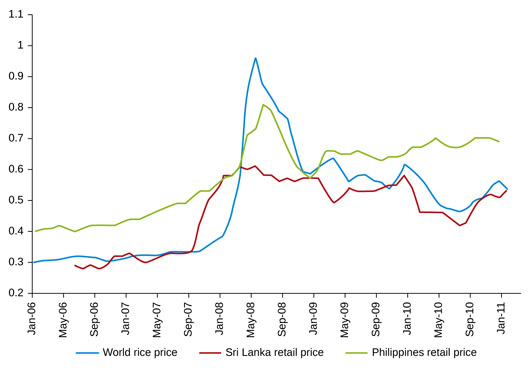

The foodgrain commodity that is most important for the majority of Asian consumers is rice, which remains the grain that is dominantly consumed by large parts of the population in most of the region. Figure 6 indicates the behaviour of rice prices in Sri Lanka and the Philippines, in relation to the global price.

Source: FAO GIEWS, viewed on March 19, 2011.

Note that the two are rather different as rice-producing and rice-consuming countries. While Sri Lanka exports cash crops, it has achieved near self-sufficiency in rice in recent times, thanks to significant efforts to promote domestic rice cultivation. Rice is of course by far the dominant foodcrop, accounting for around 60 per cent of dietary requirements. Philippines, on the other hand, is a rice producer, but depends on imports for between 15 to 20 per cent of domestic consumption, so that it is likely to be far more affected by international prices. Rice accounts for around 46 per cent of dietary requirements in the Philippines.

Retail rice prices in Sri Lanka (referring to Colombo in Figure 6) tracked international prices very closely. Other than the extreme peak of June 2008, retail prices were nearly identical to global trade prices, despite the lack of reliance on imports. So, the global price volatility has been reflected even in a country that is largely self-sufficient in rice. In the Philippines the story is even more worrying. Rice prices here (referring to retail prices in Metro Manila) rose dramatically in response to global price movements, almost to the same level as the peak in June 2008, came down as global prices fell in the second half of 2008, but since then have actually been higher than in international trade. Further, rice prices in the Philippines have continued to rise even as they have stabilised in the global market.

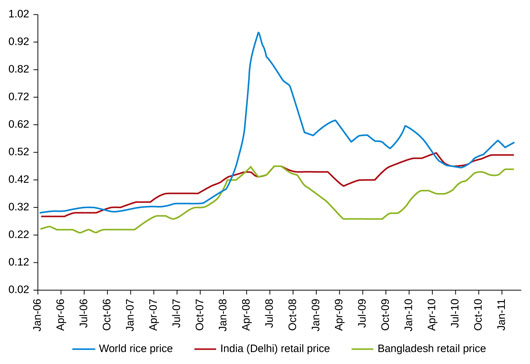

Figure 7 describes retail price movements for rice in India (Delhi) and Bangladesh (national average). It is worth remembering that retail prices vary quite significantly across towns and cities in India; even so, this provides an important indication of recent patterns.

According to FAO data, India is completely self-sufficient in rice, whereas Bangladesh currently is only 97 per cent sufficient, having to import around 3 per cent of its requirement (possibly more, if cross-border smuggling is taken into account). While retail rice prices in India did not peak in June 2008, they have risen steadily and increased by around 26 per cent in the second half of 2010 alone. In Bangladesh there has been much greater volatility, with prices rising sharply following the global surge in 2007-08, then falling, and then rising again. In the past two years, retail rice prices in Bangladesh have increased by more than 35 per cent.

These trends in different Asian countries point to a broader trend whereby prices in domestic food markets, since 2007 in particular, are more strongly affected by and related to international price changes. This is a matter of some concern, especially in the context of the ongoing extreme volatility in global prices.

The recent price increases, similar to those in 2007-08 (which were followed by declines), do not represent significant changes in global demand and supply balances. Rather, once again, it is likely that a combination of panic buying and speculative financial activity is playing a role in driving world food prices up well beyond anything warranted by real quantity movements. The most recent data on financial activity in commodity futures markets from the US Commodity Future Trading Commission suggest that until the end of January 2012, the net long positions of index investors had increased dramatically in commodities like wheat and corn. This is likely to have increased even more since then, given the announcements about lower levels of public stocks.

Once again, we are also seeing contango in these commodity markets, with futures prices higher than spot prices. This is a repeat of 2007 and the first half of 2008, when these prices nearly tripled. And it is not surprising, because the regulations that could prevent or at least limit such speculative financial activity are not yet in place, and there are concerns about whether they will be effective in their implementation even if they are.

We have direct recent experience of how financial speculation in commodity markets can not only create unprecedented volatility, but also affect prices in developing countries, with extreme effects on hunger and nutrition for at least half of humanity. The case for moving swiftly to ensure effective regulation in this area - and for dealing with supply issues in a serious and sustainable way - has never been more compelling.

It should be noted that there are some dissenting voices, including of those who argue that the bout of food price increases that occurred over 2006-08 possibly did not have as bad an impact on hunger and undernutrition as was earlier believed. Indeed, it is argued by some that the extent of hunger in the developing world may actually have come down significantly even during that period of dramatic food price increase.

Most estimates of increasing hunger are based on simulation exercises that take note of global food price increases and assume that these will lead to domestic increases in food price, which will in turn affect food consumption, especially of poorer families. Against this, it is argued that such exercises do not take account of increasing money incomes and people's choices about what to consume.

A recent paper by Derek Headey argues, based on calculations using a Gallup World Poll, that global self-reported food insecurity fell from 2005 to 2008, with the number ranging anywhere between 60 million to 250 million (Headey 2011). According to Headey, "These results are clearly driven by rapid economic growth and very limited food price inflation in the world's most populous countries, particularly China and India." This idea has also been taken up by others like Dani Rodrik.

Of course, there are significant problems with using self-reporting of hunger at the best of times. The Gallup Poll asks the question: "Have you or your family had any trouble affording sufficient food in the last 12 months?" The percentage of respondents who answer "yes" to this question is taken as a measure of national food insecurity. It is worth looking carefully at the Gallup Poll methodology before we decide to jump to hard conclusions, though. The Gallup report on its food security survey notes that it is based on telephone and face-to-face interviews conducted through 2005, 2006, 2007, and 2008, with randomly selected samples of respondents (typically around 1,000 residents) in 134 countries - hence a total of less than 140,000 people across the world – and only 1,000 respondents even in large countries like India. The distribution of the sample across urban and rural locations, or by income category, is not clear at all, nor is the proportion that was contacted by telephone. This is not exactly a solid basis on which to draw major conclusions about the extent of global hunger. The Gallup Poll analysts themselves do not seem to think they can make inter-temporal comparisons based on these data: their own conclusion is that "even before the crisis, affording food was a challenge for many." Therefore, basing a major conclusion on such weak "self-perception" data, as Headey does, is not justifiable.

Of course, there may be differences in the impact of global food prices upon consumers in developing countries, depending on the extent to which such prices are transmitted to domestic retail food prices, as well as the opportunities of earning incomes that allow more expensive food to be purchased. It is also true that the negative effect of food prices can be mitigated by other factors and policies such as employment schemes, subsidised food distribution, and so on. Even so, it is indisputable that the main mechanism through which higher global food prices affect people remains domestic food prices. Here, the bad news is that the international transmission of increases in food prices has generally been rapid (and is getting faster and more complete), while the downward movements have not been transmitted as much.

Significantly, even in India, a country that is taken (along with China) by Headey and others to be a major part of the explanation of the supposedly surprising result of reduced food insecurity, food prices have risen sharply over the past few years. The more disturbing feature is that domestic prices in India have increased along with international prices, but there has been little transmission of downward price trends, indicating some kind of ratchet effect in domestic prices.

This evidence clearly calls for more detailed investigation into the factors operating at different levels in various countries, and particularly the policy mix that will enable countries with large hungry populations to withstand the current global volatility in food prices.

Policy Recommendations

Changes in Financial Regulations

It is obvious that international commodity markets increasingly share many of the features of financial markets, in that they are prone to information asymmetry and the associated tendency to be led by a small number of large players. Far from being "efficient markets" in the sense hoped for by mainstream theory, they allow for inherently "wrong" signalling devices to become very effective in determining and manipulating market behaviour. In this context, controlling and mitigating the food crisis clearly also requires specific controls on finance, to ensure that food does not become an arena of global and national speculation. These controls should include very strict limits (indeed bans) on the entry of financial players into commodity futures markets; elimination of the "swap-dealer loophole" that allows financial players to enter as supposedly commercial players; and the banning of such markets in countries where public institutions play an important role in grain trade. Below, some of the forms of such regulation are briefly noted. These include some regulations that have already found their way into legislation, for example in the US Financial Reform Law (the Dodd-Frank Bill, as it is widely referred to) as well as proposals being considered by the European Union. But they also include further measures that may be necessary if such major speculative activity is to be curbed effectively.

Improving Transparency and Disclosure of Positions

A simple premise underlying any well-functioning market is that market participants are well-informed about the actual conditions in the market. Markets where information is limited and opaque are highly vulnerable to rumours and herd behaviour (Shiller 2005). Such markets can thereby be readily manipulated by large-scale traders who are able to achieve dominant positions in them. Thus, the first step towards creating more stable and well-functioning commodities futures markets, and moving commodities futures market trading back to regulated exchanges, is for accurate information to be widely and cheaply available.

The rules proposed by the European Commission (2010), which envisage, inter alia, central clearance requirements for standardized contracts, including those relating to index funds, would also help improve transparency and reduce counter-party risk. In order to capture contracts that are primarily used for speculation rather than for hedging commodity-related commercial risk, the contracts to which such clearance requirements would apply should exempt those for which transactions are intended to be physically settled.

Moving Commodity Futures Trading on to Regulated Exchanges

There is a very strong case for moving all such trade off over-the-counter (OTC) markets and on to regulated exchanges. This will introduce greater transparency and oversight, and enable more effective regulation of investor activity in such markets, consistent with the regulatory standards that prevailed in the United States prior to 2000 and that are being re-established through the Dodd-Frank Financial Reform Bill. Prior to 2000, the organizing principle of the regulatory system in the United States was precisely to bring trading on regulated exchanges under the control of the CFTC. Trading through exchanges entailed four major regulatory tools: (1) the disclosure of positions by traders; (2) capital requirements for organizers of exchanges; (3) margin requirements for traders; and (4) position limits for traders. All of these are regulatory tools that can be applied effectively in other settings (such as the EU) as well, and in fact the proposed EU legislation includes these provisions (European Commission 2010).

Information on Physical Stocks

Of the multiple reasons for poor data on stocks, a major one is that a significant proportion of stocks is now held privately, which makes information on stocks commercially sensitive. As a result, stock data published by international organisations are an estimated residual of data on production, consumption, and trade. Enhanced international cooperation could improve transparency by ensuring public availability of reliable information on global stocks.

Capital Requirements

Regulated exchanges in the United States, even during the era of deregulation, operated with capital requirements that were applied to registered futures commission merchants (FCMs). These are firms that accept funds from customers or use their internal funds to trade on exchanges. The purpose of these capital requirements was precisely to guard against excessive riskiness on the part of brokers and futures trading merchants. The problem with deregulation was that traders could avoid these regulations by trading over the counter. Capital requirements are usually designed to be static, in that the same requirements are maintained regardless of conditions. To operate more effectively in dampening speculative bubbles, the requirements should be stiffened during the upward phase of a bubble. Capital requirements could also be relaxed during slumps, to the extent that, in such periods, encouraging market trading would be beneficial. However, it should also be noted that during the recent commodity price boom, physical traders found it harder to meet the rising capital requirements and therefore were not able to use the market (UNCTAD 2011).

Margin Requirements

Margin requirements mean that traders have to use their own cash reserves, in addition to borrowed funds, to make new asset purchases. There are two overall purposes of margin requirements. The first is to discourage excessive trading by limiting the capacity of traders to finance their trade almost entirely with borrowed funds. The second is to discourage excessively risky trading by forcing traders to put a significant amount of their own money at risk when undertaking new asset purchases. Generally, margin requirements, unlike capital requirements, are designed to operate dynamically - that is, they are stiffened during booms and relaxed during slumps. Operating as such, they do have the capacity to contribute effectively towards stabilisation of commodities futures markets. However, changes in margin requirements can adversely affect smaller hedge traders as compared to larger speculative investors. For example, large speculative traders could bid up margin requirements on exchanges by increasing price volatility. The rise in margin requirements would then increase the costs of hedging by small traders, perhaps creating barriers for the smaller market players. One way to deal with this is to establish differential margin requirements for traders operating at different levels. Another is to set clear position limits for trading, as discussed below.

Position Limits

Position limits can be established both for individual market participants and categories of market participants (such as money managers), as well as for market participants operating in the same commodity but on different exchanges. It is extremely important to set strict position limits for all types of derivatives contracts. This would give regulators the power to prevent speculation that affects the underlying physical market. Ideally, such position limits should allow commercial hedging while minimising the negative impact of excessive speculation. The purpose of position limits is to prevent large speculative traders from exercising excessive market power. Large traders can control the supply side of derivative markets by taking major positions either on the short or long side of markets. Once they control supply, they can also exert power in setting spot market prices, because they can then affect both the market perceptions and the expectations of those operating in the spot market.

The levels at which position limits should be set are also important. They should be set at levels that are relevant to controlling speculative activity. Because it is difficult to distinguish between hedging and speculative activity in a market, setting position limits relative to the same average for the overall market - say, the median level - may be as effective as or more effective than setting limits only after distinguishing commercial from index traders.

The issue of position limits is currently under discussion in both the European Union (European Commission 2010) and the United States, with the CFTC draft guidelines having been released already. Such regulatory action relating to positions for energy commodities, especially those taken by hedge funds, is also relevant for agricultural commodities. This is because it has been shown that hedge funds drive the correlation between equity and commodity markets, and that food prices have become more closely tied to energy prices (Tang and Xiong 2010; Büyükşahin and Robe 2010). However, since the limited availability of data at present makes it difficult to determine the appropriate levels for these position limits, the introduction of such limits may take longer. Meanwhile, as an interim step, the introduction of "position points" could be considered: a trader reaching a position point would be obliged to provide further data, on the basis of which regulators could decide whether or not action is needed (Chilton 2011).

The Volcker Rule for Commodity Trading

Application of the Volcker rule (which prohibits banks from engaging in proprietary trading) may also be relevant for commodity markets. At present, banks that are involved in the hedging transactions of their clients have insider information about commerce-based market sentiment. They can use this information to bet against their customers. Such position-taking gives false signals to other market participants and, given the size of some of these banks, can move prices away from the levels determined by fundamentals, in addition to provoking price volatility.

At the same time, a similar rule could be applied to physical traders, prohibiting them from taking financial positions and betting on outcomes that they are able to influence due to their strong economic position in the physical market. (Note the example of the Glencore case, described in the Financial Times of 24 April 2011.) Obviously, such rules must incorporate position limits that recognise the need for legitimate "hedging."

Exemptions from Regulations

The new Dodd-Frank regulations in the United States do offer opportunities for exemption from regulations for certain classes of traders. The first set of exemptions is for commercial end-users seeking to use agricultural swap agreements. This provides an exemption to any swap counter-party that: (1) is not a financial entity; (2) is using the swap to hedge or mitigate commercial risk; and (3) notifies the CFTC or Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) how it generally meets its financial obligations arising from entering into uncleared swaps. Beyond these, the CFTC (as well as the SEC) may make any exemption it deems appropriate from the prescribed position limits.

Of course, the aim in offering such exemptions is to prevent the Dodd-Frank regulations from imposing excessive burden on derivative market participants who are legitimate hedgers and who are thereby not contributing to destabilisation of markets. While this may in principle be a desirable goal, in practice, it is difficult for regulators to decide which market participants truly merit exemption by established standards. This is evident from the experience with the so-called "Enron loophole" introduced in the Commodity Futures Modernization Act in the USA in 2000. The loophole exempted over-the-counter energy trading undertaken on electronic exchanges from CFTC oversight and regulation. Enron quickly seized this market opportunity to create an artificial electricity shortage in California in 2000-01, which led to multiple blackouts and a state of emergency, and, finally, the collapse of Enron itself as well as its erstwhile big-five accounting firm, Arthur Andersen. Nevertheless, following Enron's example, other large market players subsequently took advantage of similar loopholes: the "London loophole" for nominal foreign market trading, and the "swap dealer loophole" which permitted all swap traders to move into OTC markets. The overall effect was to enable the OTC markets to flourish alongside the regulated markets. This suggests that the only way to prevent making invidious distinctions between traders in allowing exemptions is to establish viable regulations that apply to all traders, without exception. Exemptions from such position limits should not be granted to hedge financial risk, as is still the case in the Dodd-Frank legislation in the United States, where swap dealer exemptions (which also apply to commodity index funds) are granted with regard to position limits imposed on some agricultural commodities.

Other Measures Required

Clearly, in the current uncertain global economic context, even financial regulation that prevents purely financial players from entering commodity futures markets in sufficient volume to affect prices and destabilise markets will not be sufficient to prevent price volatility. A range of other measures is required to introduce some measure of stability especially in international food markets. Some of these possible measures are briefly outlined below.

Rebuilding Stocks and Creating Strategic Grain Reserves

Supply-side measures are also important in addressing excessive commodity price volatility. These are of particular relevance for food commodities, because any sudden increase in demand or major shortfall in production - or both - when stocks are low, will rapidly lead to significant price increases. Hence, physical stocks of food commodities urgently need to be rebuilt to adequate levels, in order to moderate temporary shortages and to be available as emergency food supplies for crisis relief to the most vulnerable sections of the population.

Von Braun and Torero (2008) have proposed a new, two-pronged global institutional arrangement: a minimum physical grain reserve for emergency responses and humanitarian assistance, and a virtual reserve and intervention mechanism. The latter would enable intervention in the futures markets if a "global intelligence unit" were to consider market prices as differing significantly from an estimated dynamic price band based on market fundamentals.

Taxation as a Means of Price Stabilisation

Another means of price stabilisation in commodity markets could be to tax excess trading profits in periods of boom. A multi-tier transaction tax system for commodity derivatives markets has been proposed. Under this scheme, transaction tax surcharges of increasing scale would be levied as soon as prices start to move beyond the price band defined either on the basis of commodity market fundamentals (Nissanke 2010) or on the basis of an observed degree of correlation between the return on investment in commodity markets, on the one hand, and equity and currency markets, on the other.

Compensatory Financing by the IMF

The IMF's compensatory financing facility was first activated in the 1970s in response to the global oil price spikes. There is a strong case for redeploying it to provide unconditional finance to food-importing countries affected by global price increases. Some proposals along these lines have already been made (Raffer 2009).

Improving Agricultural Productivity in Developing Countries

There is an obvious need for incentives to increase agricultural production and productivity in the developing countries, particularly for food commodities. These incentives could include a reduction of trade barriers and of domestic support measures in the developed countries. Increased public investment is clearly necessary in this context.

The food crisis in developing countries is something that has been created and is currently being exacerbated by the working of deregulated international finance, which continues to have an adverse impact even when these financial markets are themselves in crisis. Developing countries are caught in a pincer movement: between volatile global prices on the one hand, and reduced fiscal space and depreciating currencies on the other.

It is clear that a resolution of the food crisis requires strong government intervention to protect agriculture in developing countries, providing greater public support for sustainable and more productive and viable cultivation patterns, and creating and administering better domestic food distribution systems. But it also requires international arrangements and cooperative interventions, such as strategic grain reserves, commodity boards, and other measures, to stabilise world trade prices. It is important to think of unconditional financing mechanisms that would compensate food-importing developing countries for sudden spikes in food prices, along the lines suggested by Raffer (2008). In addition, such mechanisms could encompass compensation for sharp currency depreciations that raise the price of food in domestic currency terms.

Managing and Regulating Corporate Retail

As has been argued by the UN Special Rapporteur on the Right to Food, Oliver de Schutter, it is necessary for competition authorities within countries as well as global legal regimes to be in place to prevent such rampant abuse of power. Regulation and control are necessary to prevent some of the following tendencies of large retailers:

- directly or indirectly imposing unfair purchasing or selling prices, or other unfair conditions;

- limiting production, markets of technical development to the prejudice of suppliers;

- applying dissimilar conditions to equivalent transactions with other trading partners, resulting in those parties being placed at a competitive disadvantage;

- making the conclusion of contracts subject to acceptance by the other parties of supplementary obligations that have no connection with the actual subject of such contracts.

Clearly, framing such regulations and enforcing them is a mammoth enterprise. But it must be done in all situations where the concentration of market power in the hands of a few large buying forms is leading to such malpractices.

Notes

1 Some of the research for this paper was carried out under the AUGUR Project, School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS), University of London, U.K., in 2011-12.

2 See http://www.fao.org/giews/english/gfpm/GFPM_01_2011.pdf, viewed on May 31, 2012.

3 http://faostat.fao.org/site/368/default.aspx#ancor, viewed on May 31, 2012.

4 http://www.guardian.co.uk/global-development/2011/nov/23/corporate-giants-target-developing-countries, viewed on May 31, 2012.

5 See http://www.srfood.org/images/stories/pdf/otherdocuments/20101201_briefing-note-03_en.pdf, viewed on December 2010.

References

| Baffes, John, and Haniotis, Tassos (2010), "Placing the 2006/08 commodity price boom into perspective," World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 5371, July. | |

| Büyükşahin, B., and Robe, M. A. (2010), "Speculators, commodities and cross-market linkages," mimeo, November 28, available at http://ssrn.com/abstract=1707103, viewed on May 31, 2012. | |

| Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) (2010), Crop Prospects and Food Situation, Rome, December. | |

| Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) (2011). Price Volatility and Food Security: A Report by a High Level Panel of Experts on Food Security and Nutrition, Rome, July. | |

| Chandrasekhar, C. P., and Ghosh, Jayati (2011), "The transmission of global food prices," http://www.macroscan.org/fet/mar11/fet220311Transmission.html, viewed on May 31, 2012. | |

| Ganesh, Aravind (2011), "The right to food and buyer power," German Law Journal, vol. 11, no. 11; available at http://www.networkideas.org/featart/jan2011/Aravind_Ganesh.pdf, viewed on May 31, 2012. | |

| Ghosh, Jayati (2010), "Unnatural Coupling: Food and Global Finance," Journal of Agrarian Change, January, pp. 72-86. | |

| Gilbert, Christopher L. (2010a), "Speculative Influences on Commodity Futures Prices 2006-2008," UNCTAD Discussion Paper No. 197, March. | |

| Gilbert, Christopher L. (2010b), "How to Understand High Food Prices," Journal of Agricultural Economics, 61, pp. 398-425. | |

| Headey, David (2011), "Was the global food crisis really a crisis? Simulations versus self-reporting," IFPRI Working Paper No. 1087; available at http://www.ifpri.org/publication/was-global-food-crisis-really-crisis, viewed on May 31, 2012. | |

| Hernandez, M., and Torero, M. (2010), "Examining the Dynamic Relationship between Spot and Future Prices of Agricultural Commodities," IFPRI Discussion Paper 00988, International Food Policy Research Institute, Washington D C, June. | |

| Irwin, S. H., and Sanders, D. R. (2010), "The Impact of Index and Swap Funds on Commodity Markets," OECD Food, Agriculture, and Fisheries Working Papers, no. 27. | |

| Mayer, Jorg (2009), "The Growing Interdependence Between Financial and Commodity Markets," UNCTAD Discussion Paper No. 195. | |

| Mayer, Jorg (2011), "The growing financialisation of commodity markets: an empirical investigation," mimeo, UNCTAD, Geneva, March. | |

| Raffer, Kunibert (2008), "A food import compensation mechanism: A modest proposal to reduce food price effects on poor countries," paper presented at G24 Technical Group Meeting, United Nations, Geneva, Switzerland, September 8-9. | |

| Robles, Miguel, Torero, Maximo, and von Braun, Joachim (2009), "When Speculation Matters," IFPRI Policy Brief 57, International Food Policy Research Institute, Washington D C. | |

| Roncaglia, Alessandro (2003), "Energy and market power: an alternative approach to the economics of oil," Journal of Post Keynesian Economics, vol. 25, no. 4, pp. 641-59. | |

| Tang, K., and Xiong, W. (2010), "Index investment and financialisation of commodities," Working Paper 16385, National Bureau of Economic Research, Princeton University, Cambridge (Mass.), September. | |

| United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) (2009), Trade and Development Report, 2009, United Nations, Geneva, Chapter 2: "The Financialisation of Commodity Markets," pp. 52-84. | |

| United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) (2011), Trade and Development Report, 2011, United Nations, Geneva. | |

| UN-DESA (2010), World Economic and Social Prospects 2010, United Nations, New York. | |

| Wise, Timothy, and Murphy, Sophia (2012), "Resolving the Food Crisis: Assessing global policy reforms since 2007," GDAE and IATP, January; available at http://ase.tufts.edu/gdae/Pubs/rp/ResolvingFoodCrisis.pdf, viewed on May 31, 2012. |

Glossary

| backwardation | The market condition when the price in the futures market is below the price in the spot market. |

| contango | The market condition when the price in the futures market is above the price in the spot market. |

| derivatives | See futures market. |

| futures market | A market in which there is buying and selling of a commodity for delivery at a future date, or a within a specified period. Since the buyer has the option to ask for delivery at any time within the period, a futures contract is also sometimes called an options contract. The buyer of the contract is said to be "long," and the seller of the contract is said to be "short." Since these contracts involve bets on the rate of change of the price over the specified period, they are also known as "derivatives." |

| hedge fund | Less regulated manager of financial investment portfolios. |

| index trader | Financial asset manager who deals in futures markets hoping to benefit in changes in prices (the value of the index) |

| long position | The holder of a long position (buyer in a futures contract) will benefit if the spot price rises. |

| margin requirements | The amount that an investor on an exchange must deposit as margin before being allowed to trade. |

| OTC (over-the-counter) trading | Bilateral trades between parties that are not done through a recognized exchange, and therefore not possible to regulate or control in any way. |

| position limit | A limit on the maximum number of "positions" (physical volumes of contracts) a single player can hold in an exchange. |

| short position | The holder of a short position (seller in a futures contract) will benefit if the spot price falls. |

| spot market | A market for trading in immediate delivery. |

| swap trading | The trading of an asset or liability in exchange for one with slightly different characteristics (such as longer/shorter repayment period, different rates of interest, different currencies, etc.). |