ARCHIVE

Vol. 5, No. 2

JULY-DECEMBER, 2015

Research Articles

In Focus*

Review Articles

Tribute

Field Reports

Amalendu Guha: A Personal Memoir

M. S. Prabhakara*

*Writer, former Assistant Editor, Economic and Political Weekly, and former North East Correspondent and South Africa Correspondent, The Hindu.

I do not remember when or where I met Professor Amalendu Guha (AG) for the first time, though this should have been probably some time in the late 1960s or early 1970s, and almost certainly in Guwahati. I was in those days teaching at the Gauhati University, which I had joined in early 1962, and living in the relatively isolated University campus seven miles to the west of the city, midway between the airport and the city proper. AG, who had been teaching in Darrang College, Tezpur, had moved to the Gokhale Institute in Pune in 1965.

I had heard about AG even before I met him, not so much as a scholar but as a teacher, part of the academic community to which I belonged, who had been detained with scores of Communist Party members in Assam in the wake of India’s China War of late 1962. When the war broke out and wide-scale preventive arrests followed, I had been in Guwahati, strictly speaking in the Gauhati University campus, with little contact with Guwahati, let alone Assam, for just about eight months. I knew little of the larger issues involved in the border conflict, though I was aware of the existence of laws providing for preventive detention, thanks to listening to a speech by A. K. Gopalan sometime in 1952, in Kolara, my home town (see my article on the editorial page of The Hindu, April 19, 2010). Assam was some sort of a “forward area” in the Eastern Sector during that brief war, and Tezpur, the place where Amalendu Guha was working, even more so. Indeed, Tezpur, the headquarters of Darrang district, had been “abandoned” (ordered to be evacuated by the higher echelons of civil administration) in panic, apprehending ”Chinese occupation.” Ironically, even as chaos ruled with panic evacuation, China announced its decision to withdraw its troops, having made its point tellingly on the border issue when its troops reached the plains of Assam after crossing the hills in what was then known as the North East Frontier Agency (NEFA), now Arunachal Pradesh.

I had joined the Gauhati University as a lecturer in English in February 1962, but our paths had not crossed. It was only because two members of the University community, both active in trade union work related to Gauhati University Workmen’s Union and both members of the Communist Party of India, were also arrested and detained in the context of the border war that I realised that, even if the war did not come to our doorstep, the detention of persons suspected to be security threats had certainly brought war-related issues uncomfortably close to home. However, most of the detained persons, including Dr Guha and others, were released within months, following the unilateral declaration of ceasefire by China and the withdrawal of Chinese troops from areas they had overrun.

This much by way of context and background. My first clear memory of meeting AG was when he dropped by at my home in the University campus sometime in the early 1970s, accompanied by a common friend. When we met it was evident that he knew about me a bit. Perhaps he had seen some of the articles and book reviews, much of them poor stuff as they seem in retrospect, that I had begun to contribute while teaching at Gauhati University to Now and Frontier, and later to Economic and Political Weekly, where he was a highly regarded and established writer. We had a good chat. I had a feeling he was sizing me up, trying to figure out the whys and wherefores of my interest in Assam. I had heard he was writing a book on electoral politics and the freedom struggle in Assam and asked him when the book was likely to be published. He said the writing was over, he was now going over the draft, and expected to pass on the typescript to the publisher before the end of the year. We talked about the book a bit, and then with some trepidation I asked if I could have a look at the manuscript, for I was sure I would be greatly benefited by reading it. He then took out from his tattered briefcase a bulky packet, which turned out to be a third or fourth carbon copy of about 400-plus typed pages on very thin paper (called “India paper”). I can even now recall the thrill I felt as I held that bulky package. Writing this in mid-2015, I cannot but reflect on the world that that typescript, indeed that tattered briefcase, represented. I am mentioning these details because integral to the work culture of poorly paid college and university teachers who took their work seriously in those days and who considered research as part of their teaching were rickety typewriters and typists in poorly paid jobs moonlighting on more substantial typing of theses and books. Most teachers did not own a typewriter, did not keep stocks of carbon paper sheets and quires of India paper, nor did they carry bulky manuscripts and typescripts stuffed in tattered briefcases — a world that is dead and gone. AG graciously left the package with me, accepting my assurance that the typescript would be returned safe and intact in a week.

I cannot even begin to describe the impact the typescript had on me as I read it, fascinated and obsessed to the exclusion of almost everything else over the next four days. The bits and pieces I had written till then seemed so pathetic, horribly jejune, really less than nothing. The realisation that I had been pontificating with brash confidence on issues about which I knew less than nothing was truly mortifying.

Soon, larger national issues, beginning with the nationwide railway strike and the declaration of national emergency, which was causally related to the measures taken to suppress and break the railway strike – though the proximate cause was the judgement of the Allahabad High Court nullifying the election of Indira Gandhi to the Lok Sabha – more or less clinched my wavering mind on whether I should continue to be a teacher of English for the rest of my life, or do something else. Thus it was that I resigned from the University and left Guwahati and Assam -- for good, as I then thought -- in December 1975, to join Economic and Political Weekly in Bombay as a member of its editorial staff.

No, I am not indulging in anecdotage, the rambling is relevant to point out how AG, who had joined the Centre for Studies in Social Sciences, Calcutta, in 1973, ever so gently and in a way only I could parse, cured this Mr Know-All of the brashness that was a feature of some of my early interventions on social and political developments in Assam.

It came about thus. Soon after being sworn in as President in August 1974, Fakhruddin Ali Ahmed visited Assam, his home State, and as to be expected was widely feted by several organisations. I attended one such reception, organised in the premises of the Haji Musafirkhana in Guwahati and attended predominantly, but not solely, by Assamese speaking Muslims in Guwahati. It was a small function, an audience of about 400, no security hassles of the kind that are the rule now, people moving in and out of the hall, all very informal. At one point as boring speeches were being made, a few of us came out for a smoke and a chat. Naturally we also talked about the nation’s first Assamese President, and one or two of the friends made some amiable jibes about the manner in which this Assamese President spoke the language. Not to labour the obvious point, the Assamese spoken by our first Assamese President fell considerably short of the high standards of Assamese (intonation, accent, grammar and syntax and vocabulary, and so on) of most Assamese speakers, including Assamese Muslims. Eager to make a “story,” I sent off a brief report, less than a thousand words, probably to Frontier or Economic and Political Weekly (I was still teaching and not a full time professional journalist) on the President’s visit, with a light-hearted aside on his less than perfect Assamese. The report appeared, and like all such reports, sunk without a trace, though some friends read it and it was liked by those to whom I showed it -- nothing controversial, nothing substantial, just a dose of anodyne. Sunk it may have without a trace, but AG’s sharp eyes did not miss the silly arrogance of that frivolous and ill informed aside, as I was to realise a few years later when I was with Economic and Political Weekly. Those who want to find more about this may delve into the footnotes to the contributions in pages of Economic and Political Weekly on what is now commonly referred to as the Cudgel of Chauvinism debate. Happily I was not directly named.

I am sorry this obituary tribute is turning out to be more about my relation with AG than about the life and work of AG. However, even if I were to be competent to make a scholarly assessment of his life and work, I am in no position to attempt one. Two or three years ago, I sent off all my books and papers relating to Assam and the rest of the region to the Omeo Kumar Das Institute in Guwahati, which is also the repository of AG’s books and papers. I now have only my memories to guide me. Of these I now speak.

Despite the well deserved though mildly administered admonishment I received, I continued to be in the good books of AG; his goodwill and affection did not waver. During my years with Economic and Political Weekly (1975-83), when AG was with the Centre for Studies in Social Sciences, Calcutta, whenever I happened to visit or pass through the city, I invariably spent time with him and other Assamese friends in the city, and with some of his colleagues at the Centre.

Many years later, after I returned to Guwahati from an eight-year absence in South Africa (1994-2002) and retired from The Hindu, I learnt that he had a role (along with Dr Ashok Mitra) in the paper recruiting me in June 1983, when I was in a desperate situation, living a week-to-week existence in seedy paying guesthouses in Bombay, enabling me to “return home” as it were. Indeed, during my last eight years in Guwahati, I was for the first time living in a flat of my own. This was also the period when the formality of our relationship began to ease up, and I used to visit him at least once a month, if not more often, just drop by without even calling, on the off chance he would be home, which most often he was, for a chat, tea, and political gossip and conversation. He was also inquisitive about my years in South Africa, politically inquisitive unlike most other Indians, who were only interested in knowing if I had met Nelson Mandela. I remember one detailed conversation at my place when he questioned me closely about the nature of South Africa’s tripartite alliance comprising the African National Congress, the South African Communist Party (SACP), and the Congress of South African Trade Unions (COSATU), and we had a free exchange of views on whether the Communist Party of India had miscalculated the strength and mass appeal of the Congress Party in the days before Independence. I also remember him closely questioning me about the SACP’s formulation, Colonialism of a Special Type (CST), to describe the linkages between colonialism in the conventional sense, and apartheid, the unique way in which colonialism functioned, and about the issues of class and race, rather like class and caste in India, which seemed to defy all the texts as one understood them.

I do not want to think too much about my last two visits to AG, in June 2011 and November 2012. The memory of those visits is painful. When death came to him, it came as a release. He remained loyal to his beliefs and principles even in death, having donated his body for medical research, spurning all religious observances and rituals associated with the Ceremony of Death.

Go well, friend, go in peace.

|

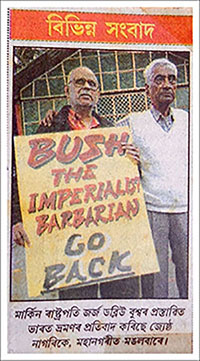

| The author (left) with Amalendu Guha at a demonstration in Guwahati to protest against the visit of George W. Bush to India in 2006. |