ARCHIVE

Vol. 1, No. 1

JANUARY-JUNE, 2011

Research Articles

Research Notes and Statistics

Field Reports

Symposium

Book Reviews

Changing Lives and Landscapes:

A Case Study of Employment Guarantee

in Bonkati Gram Panchayat

Aparajita Bakshi

Senior Research Fellow, Sociological Research Unit,

Indian Statistical Institute, Kolkata, aparajita.bakshi@gmail.com.

This is a field report on the implementation of the

NREGS – the National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme, to use its full title –

in Bonkati village, Kanksa block, Barddhaman district.

The NREGS is the most important development scheme to be introduced by the Government of India in recent years. The implementation of the scheme in West Bengal has, inevitably, been watched closely, and the verdict has been mixed. Some commentators, referring particularly to the performance indicators for 2007–08 and 2008–09, have characterized the performance of the Government of West Bengal (GOWB) as inadequate or worse, and two have described the attitude of the State Government towards the scheme to be, on the whole, “ambivalent.”1

On the other hand, it is also clear that, away

from the attention of the media, the NREGS has dramatically been changing lives

and landscapes in parts of the State. Two districts of the State, Barddhaman

and North 24 Parganas, were among 24 districts in the country to receive the “Excellence

in NREGA Administration 2009” award earlier this year (Government of India 2010).

Bonkati village provides an excellent example of

the potential of the NREGS in a State that has had a basic land reform and,

within this State, in a pro-poor panchayat.

Geography

and Population

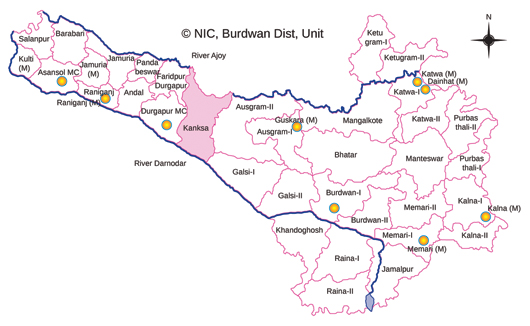

Kanksa block is located in the western part of

Barddhaman district. The block is bounded by the Ajoy river in the north and

the Damodar river in the south (see Figure 1). A smaller river named the Kunur flows

through the block. The total geographical area of the block is 282.9 square kilometres.

One-fourth of the land area of Kanksa is covered by forest. At the Census of

India 2001, the total population of Kanksa was 1,50,829, of which 31 per cent

were Dalits and 9 per cent were Adivasis (Table 1).

Table 1 Land use and population of Kanksa block, 2001

| Total area | Net area under cultivation | Net area under forests | Population | ||||

| Total | Male | Female | SC | ST | |||

| 282.90 sq. km. | 140 sq. km | 74.3361 sq. km | 1,50,829 | 78,405 | 72,424 | 46,846 | 13,095 |

Notes: SC: Scheduled Caste; ST: Scheduled Tribe.

Source: Census of India 2001.

Bonkati gram panchayat is located along the

river Ajoy. The gram panchayat consists of 16 mouzas that cover a land area of 18.95 square kilometres.2 The total

population of the gram panchayat in 2001 was 15,584, of which 44 per cent were

Dalit and 25 per cent Adivasi.

The two rivers that flow along Kanksa block are

prone to seasonal flooding, causing much loss to lives and livelihoods in the

block. Major floods occurred in the area in 1978 and 2000. Apart from the loss

of lives, livestock, and assets during these floods, large tracts of fertile agricultural

land were covered with sand, making the land unfit for cultivation. In Bonkati

gram panchayat alone, more than 1,000 bighas

(333.3 acres) of flood-affected land remained uncultivable from 1978, seriously

affecting the livelihoods of the people.

Implementation

of Nregs in Bonkati

The implementation and performance of NREGS in West Bengal has been uneven. The State Government reports that “although the average days of employment calculated over the entire state or even any district is not high, in areas with high demand for work, wage employment could be provided for a substantial number of days. These are mostly areas with degraded land and low intensity agriculture” (Government of West Bengal 2009).

The average number of person-days of employment generated per household was only 26 in 2008–09. The total expenditure on NREGS in the State in the financial year 2008–09 was Rs 940.38 crores, and the expenditure per gram panchayat was Rs 26.86 lakhs (ibid.).3

Kanksa block, however, was an area where the NREGS was utilized to its full potential. The NREGS performance indicators show very high levels of employment generation and expenditure in the block. Implementation of the NREGS in Bonkati gram panchayat and Kanksa block is summarized in Tables 2 and 3. The average number of days of employment per household in 2008–09 was 118 in the block and 172 in Bonkati.4 In the year 2009–10, 91 person-days of employment per household had been generated by 31 January. The participation of Dalit and Adivasi households in total employment is much higher than their share in the population of the village and the block. The participation of women was higher than the stipulated one-third in Bonkati, and exactly one-third for the block as a whole in 2008–09. The participation of women increased in 2009–10.

Table 2 Employment under NREGS, Bonkati gram panchayat and Kanksa block, March 2008 to January 2010

| Period | Gram panchayat/Block | No. of households demanded for employment | No. of households provided employment | Person-days generated | No. of households completed 100 days | Average person-days per household | |||||

| SC | ST | Muslim | Other | Total | Women | ||||||

| Mar 2008 to Feb 2009 | Bonkati | 1,451 | 1,451 | 1,42,128 | 71,771 | 0 | 36,125 | 2,50,024 | 1,02,509 | 1,279 | 172 |

| Kanksa block | 9,470 | 9,470 | 6,62,977 | 2,49,584 | 34,292 | 1,71,776 | 11,18,629 | 3,75,120 | 3,302 | 118 | |

| Mar 2009 to Jan 2010 | Bonkati | 3,290 | 3,290 | 1,91,507 | 77,815 | 0 | 30,359 | 2,99,681 | 1,61,176 | 580 | 91 |

| Kanksa block | 20,650 | 20,650 | 9,54,013 | 2,95,452 | 41,371 | 1,70,755 | 14,61,591 | 6,72,680 | 1,563 | 71 | |

Source: Monthly Progress Report under National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme (NREGS), obtained from Kanksa block office.

Table 3 Financial performance of NREGS, Bonkati gram panchayat and Kanksa block, March 2008 to January 2010

| Period | Gram panchayat/Block | Total funds available | Expenditure | ||||

| Unskilled wages | Semi-skilled and skilled wages | Material | Administrative | Total | |||

| Mar 2008 to Feb 2009 | Bonkati | 2,51,03,915 | 1,84,21,289 | 7,00,648 | 58,79,524 | 43,500 | 2,50,44,961 |

| Kanksa block | 10,56,29,927 | 8,80,66,587 | 27,47,342 | 1,41,86,040 | 3,74,163 | 10,53,74,132 | |

| Mar 2009 to Jan 2010 | Bonkati | 3,34,81,243 | 2,45,56,571 | 7,48,266 | 75,14,889 | 40,000 | 3,28,59,726 |

| Kanksa block | 15,46,24,874 | 12,06,15,032 | 46,93,628 | 2,30,78,510 | 6,17,816 | 14,90,04,986 | |

Source: Monthly Progress Report under National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme (NREGS), obtained from Kanksa block office.

Allocation of NREGS funds to panchayats is done

on the basis of the demand for funds by individual panchayats. These demands

are made on the basis of project plans made by the panchayats. Bonkati gram

panchayat has not only been able to prepare project plans and demand

substantial funds for employment generation, but has also been able to fully utilize

those funds.

In 2008–09, the total expenditure of Bonkati

gram panchayat was Rs 2.5 crores. In the same year, the State average was Rs

26.86 lakhs per gram panchayat. The gram panchayat spent 99.8 per cent of the

total funds made available to it. In the financial year 2009–10, Bonkati had

already spent 98 per cent of the funds available to it by 31 January, an

expenditure that amounted to Rs 3.28 crores.

Delineating Bonkati’s Development Achievements

NREGS is a wage-employment scheme aimed to

provide unskilled wage employment for a period of 100 days annually during the

lean season. The difference between NREGS and wage-employment schemes in the

past mainly lies in the scale of the scheme and the implicit acknowledgement of

the right to employment under NREGS.

In Bonkati, the design and implementation of the scheme goes beyond supplementary wage-employment generation and focuses also on generating incomes from agricultural self-employment. A description of the major projects implemented under NREGS in Bonkati will explain my argument. Tables 4 and 5 show the expenditures on each type of NREGS project in Bonkati for the financial year 2008–09, and from April 2009 to January 2010.

Table 4 Total expenditure on NREGS by type of project, Bonkati, 2008–09

| Type of project | Expenditure (in rupees) |

| Road and rural connectivity | 79,80,594 |

| Land development | 1,29,68,981 |

| Pond re-excavation | 22,29,326 |

| Irrigation channels | 5,14,937 |

| Drainage | 2,71,000 |

| Kitchen gardens | 60,000 |

| Others | 30,456 |

| Total | 2,40,55,294 |

Source: Compiled from Bonkati gram panchayat annual accounts.

Table 5 Number of projects and expenditure on NREGS by type of project, Bonkati, 1 April 2009 to 31 January 2010

| Activities | No. of projects | Coverage | Expenditure (in rupees) |

|

| 1 | Water conservation and water harvesting (digging of new tanks/ponds, percolation tanks, small check dams, etc.) |

25 | 1,03,261.62 cmt. | 41,10,000 |

| 2 | Drought proofing (afforestation and tree plantation, and other activities) | 8 | 1.341 ha | 7,30,377 |

| 3 | Micro irrigation works (minor irrigation canals and other activities) | 3 | 11,44,983.74 km | 9,51,472 |

| 4 | Land development (plantation, land leveling, and other activities) |

41 | 23.73 ha | 1,39,10,642 |

| 5 | Rural connectivity | 50 | 72.50 km | 1,35,58,707 |

| 6 | Any other activity | 39 | 79,530 cft | 4,38,433 |

| Total | 166 | 3,36,99,631 |

Source: Monthly Progress Report obtained from the NREGS Cell, Bonkati gram panchayat.

Biresh Mandal, Krishak Sabha activist and former

sabhapati (chairperson) of the Kanksa

block panchayat samiti, made an interesting comment on the panchayat’s approach

to NREGS: “I assess the impact of the NREGS in three ways: How much land wealth

has been created and enhanced, and what is its impact on production? How many

cubic metres of water have been stored and what is its impact on production?

How many children have been retained in school and not forced to drop out due

to poverty?”

Reclamation

of Flood-Affected Land of Individual Holders

The most important and successful NREGS project in Bonkati was the reclamation of flood-affected land along the Ajoy river and the rehabilitation of farmers on the land. As stated earlier, some 333 acres of agricultural land in this gram panchayat were covered with sand and lay barren after the 1978 floods. The owners of the land were poor, marginal, and small farmers who did not have the resources to reclaim the land. The panchayat did not have the resources, either, to reclaim such a large land area. When the NREGS project was initiated in the gram panchayat in 2006, the panchayat, for the first time, had enough resources at its disposal to consider reclaiming the land. The proposal was supported by the gram unnayan samitis, and work started in 2007–08.5 By the time I visited the gram panchayat in February 2010, almost the entire stretch of land had been reclaimed. Most of the land (around 90 per cent) belonged to individual holders, and was returned to the owners. According to the nirman sahayak of Bonkati, Rajib Gupta, the land was owned by around 620 households, 85 per cent of them Dalit households and 12 per cent Adivasi households.6 The land is now fit for cultivation, and two crops (aman paddy in the kharif season, and potato or mustard in rabi) can be cultivated annually.7

The distinguishing feature of the project is

that the work was carried out on private land. This was made possible because

of the unique initiative of the Government of West Bengal to allow NREGS work

on land owned by Dalit, Adivasi, and marginal and small-farmer households. The

initiative was recognized by the Centre and, from March 2007, the NREGS has allowed

specific work on land owned by Dalit, Adivasi, and below-poverty-line (BPL) households.

In July 2009, the scope of the scheme was expanded to include beneficiaries of

land reform or Indira Awas Yojana, and small and marginal farmers as defined in

the Agricultural Debt Waiver and Debt Relief Scheme 2008 (Government of India

2009).

Leasing out Reclaimed Land to Self-help Groups

Of the 333 acres of flood-affected land in Bonkati, 7.28 hectares (or 18 acres) were vested with the government. The panchayat handed over this land to six Self-Help Groups (SHGs) for reclamation and subsequent cultivation. The members of the SHGs reclaimed the land for cultivation, for which they received daily wages. After reclamation, the SHGs received banana and acacia saplings, and financial assistance from the panchayat under the NREGS and Hariyali programmes, to develop banana cultivation.8 The input and wage costs of planting the crops were borne by the panchayat. The SHG members also cultivated pulses and vegetables as inter-crops. Thus the SHG members not only received wage incomes for land reclamation, but also received wages for working on the allotted land and incomes from the produce from land. The case study of Dileep Bauri of Kalimata SHG from Satkahaniya village describes the project in detail.

|

An

Experiment with Group Farming Dileep Bauri is a Dalit

small farmer-cum-agricultural worker. He owns half an acre of irrigated land,

on which he grows two crops of paddy a year. Since the production from his

own land is not enough to sustain a family of seven members (he has five

daughters aged between 18 and 9 years), Dilip and his wife also work as

agricultural wage labourers in their village and neighbouring villages, or

work in the local brick kilns. His 18-year-old daughter dropped out of school

when she was in seventh standard. She too works on the family land-holding

and as an agricultural worker. The remaining four daughters are in school.

Dileep has not migrated to other places for employment. In 2008, Dileep became a

member and group leader of the Kalimata Self-Help Group (SHG). The group

consists of 10 Dalit families. In 2009, when land

reclamation along the banks of the Ajoy was in full swing in Bonkati gram

panchayat, the Kalimata SHG was allotted 3 acres of land for reclamation and

subsequent cultivation. The land was covered with sand, 1 to 3 feet in depth.

The fields were reclaimed in three months. The entire work was done by the

members of the SHG and their families. Each family received an average of 50

days of employment at a wage of Rs 81 a day. The reclaimed land is

situated between the river and a village road. The SHG received both financial

assistance and 2,500 saplings of akashmoni,

a type of acacia, under the Hariyali scheme, to plant trees on the undulating

land that lies along the road. They received Rs 19,000 in two instalments for

labour and material costs. The approximate expenses of the SHG on fertilizers

and plant protection chemicals were Rs 3,000. The SHG members received the

remaining amount as wages for land preparation, and planting and maintenance

of the trees. In August 2009, the SHG

received 1,500 banana saplings and an initial cash payment of Rs 16,000 under

the NREGS for banana cultivation. The SHG members planted banana on 1 acre of

land. The first instalment of cash received was spent on buying manure,

fertilizer, and pesticides, and on wage payments for land preparation and

planting. The SHG subsequently received two more instalments in cash,

amounting to Rs 41,000, to meet the material costs of fencing the area and as

labour payment. According to Dileep, of the Rs 57,000 they had received in

total, they were able to retain Rs 27,000 as wage earnings, and they spent

the remaining amount on various inputs. The banana trees are expected

to yield fruit by July 2010. In Dileep’s estimation, at least 1,000 plants

will bear fruit by the end of the season. He expects each bunch of fruit to

sell for at least Rs 200. The survival rate and yield of the plants would be

better if the SHG had better access to irrigation. At present, the members

rent a pump at Rs 60 per hour to draw water from the river. This is a major

item of expenditure for the SHG. The members of the SHG

invested a part of their NREGS wage earnings to plant vegetable crops as

inter-crops with banana. They also cultivated masoor (lentil) on 0.17 acre as a rabi crop. Because irrigation

was poor, only 20 kg of masoor were

produced. The members shared the amount and Dileep used it entirely for home

consumption. The SHG has inter-cropped

0.33 acre of the banana field with brinjal, and 0.66 acre with tomato. A

small amount of chilli is also grown. Brinjals can be harvested from January

to April, and tomatoes from January to March. By 27 February 2010, when I

visited, the group had sold 2 quintals of brinjal at an average of Rs 3 per kilogram,

and 3 quintals of tomato at Rs 2 per kilogram. This was in addition to what

they retained for home consumption. Two of the 3 acres of land

that were allotted to the SHG remain fallow. According to Dileep, they will

gradually bring the land under cultivation, although lack of irrigation is a

major obstacle to using the land to its full potential. There are no shallow

tubewells or borewells near the land. Some water can be drawn from the river,

but the irrigation costs are very high. Dileep said that before

NREGS was implemented, he was able to get employment for about six months in

a year. Now, he and his family can find employment for an additional two

months. He is able to earn an additional income from cultivation on the

reclaimed land. His situation has improved, but it is still hard for a man

with a large family. Each household of the

Kalimata group including Dileep Bauri’s earned a cash income of Rs 8,470

between April 2009, when they were allotted land under the land reclamation

project, and February 2010. The amount included wage income from land

reclamation, planting and maintenance of acacia and banana plants, and income

from the sale of vegetable crops. This did not include income in kind, that

is, the lentils and vegetables used for home consumption. The bulk of the

income from the project, however, has not yet been realized. If Dileep’s

expectations of banana yield are realized, the gross value of output will be

Rs 2,00,000. The income that each household will finally receive depends on

the irrigation expenses they may have to incur, and on the survival and

health of the banana plants. Even if we assume irrigation costs to be half of

the gross value of output (which may be taken as the upper bound), each

household will earn Rs 10,000 from the sale of banana. I asked Dileep for his

views on the sustainability of joint cultivation by SHG members. His reply

was pragmatic. First, the stability of the system depends to a large extent

on the stability of the panchayat, since SHGs have only temporary user rights

on the land. Secondly, the SHG members have to be united to make the system

work. So far, Kalimata members have succeeded in deciding jointly on the cropping

pattern, and the distribution of work and output. |

Irrigation

Projects

The land reclamation project was the largest,

but not the only success story in Bonkati. In 2008–09, 15 individually owned

ponds and 3 common ponds were re-excavated. In 2009–10, 25 ponds have been

re-excavated. The annual accounts of the gram panchayat shows a total

expenditure of Rs 22 lakhs on pond re-excavation in 2008–09, and Rs 41 lakhs in

2009–10.

Most of the ponds in this region are jointly owned by groups of households and traditionally leased out to fish-worker communities.9 Six ponds that were not under such lease contracts were leased out, with the consent of the pond-owners, to SHGs for pisciculture.

The banks of the ponds are used for

afforestation under the Hariyali scheme or NREGS. Trees and vegetable crops are

grown on the banks of the ponds and these gardens are managed by the SHGs. The

SHGs use the produce from inter-cropped vegetables for their own consumption,

while the incomes from timber are shared with the owners.

The SHGs have not yet earned any income from

fish farming or the sale of timber. The panchayat officials told us that when

production starts, the income will be shared in the ratio of 2:1:1 by the SHG, the

owner, and the gram panchayat, in the case of private ponds, and in the ratio

3:1 between the SHG and the panchayat in the case of common ponds.

The

Kitchen Garden Project

The kitchen garden project for Adivasi

households was another innovative project in Bonkati. Under this project, 66

Adivasi households were given fencing material and saplings of fruit trees

(lime, guava, and mango) for kitchen gardens on their homesteads. The entire labour

requirement for fencing and developing the land had to be borne by the

households, and no wage payments were made. The households inter-cropped

vegetable crops and mustard on the same land, at their own expense. The total

expenditure on this project in 2008–09 and 2009–10 was Rs 4.8 lakhs. The

project is described in greater detail in the case study of the kitchen garden

scheme at Dangal Mahalipara.

The real lacuna in the development programmes

being implemented in Kanksa block is the stark absence of expert scientific and

technical advice on agriculture and related projects. Involvement of

agricultural universities and extension officers of the Agriculture Department

could have favourably influenced the design of the projects, and the choice of

plant and fish species, and helped to generate higher sustainable incomes.

|

A

Case Study of the Kitchen Garden Scheme Budhan Mahali, a young

Adivasi man, lives in Mahalipara, a settlement on the fringes of the forest

in Dangal village in Bonkati. Most parts of the Adivasi hamlet are on

undulating red and rocky soil (the soil is known locally as “morami”). Two years ago, as part of

the land reform, Budhan received a title deed to his homestead. In 2008–09, major

land-levelling operations were carried out under NREGS at Mahalipara. The

Adivasi households flattened patches of land contiguous to their homesteads,

and the landscape of Mahalipara underwent substantial changes. The flattened

patches were ideal for small kitchen gardens. In August 2009, as part of the NREGS,

each household was given 10 concrete beams and fencing nets, and 10 concrete

tubs and saplings of lime and guava, to begin cultivating kitchen gardens.

Budhan purchased an additional 5 beams, nets, and tubs, and enclosed an area

of about 400 square feet behind his hut for his kitchen garden. He sowed

cauliflower, radish, tomato, brinjal, and chilli in his kitchen garden. He

harvested enough vegetables in the winter to meet his family consumption

needs, as well as to distribute to friends and relatives. It is of note that every

household in Mahalipara has benefited from the kitchen garden scheme. Asked about the impact

that NREGS has had on their lives, Budhan said that each household in

Mahalipara was employed for more than a hundred days the previous year, and

that the trend continued this year. According to him, although the kitchen

garden project is a good project, the soil in the area is poor and there is

still an acute water shortage, because of which summer vegetable crops cannot

be grown. There is only one pond in

Mahalipara. The main source of water for domestic use are tubewells installed

by the panchayat. In order to address the water shortage problem in the area,

the focus of current NREGS work in Mahalipara is on the excavation of small

ponds for storing rain water. Work on the ponds was under way when I visited

the hamlet in February 2010. |

Road

and Rural Connectivity Projects

Bonkati gram panchayat has also implemented

infrastructural development programmes under NREGS. These include building

roads, culverts, and bridges, which are the most common types of projects

undertaken under wage employment programmes in India. Expenditure on road work

was the second largest component of NREGS expenditure in Bonkati in 2008–09 and

2009–10 (Rs 80 lakhs and Rs 1.3 crores, respectively).

Explaining Bonkati’s Success

Bonkati’s success in NREGS does not only lie in

the creative design of projects that take local needs and demands into account,

but also in their efficient execution. Two features of the implementation of

NREGS define its success in the gram panchayat and block.

Convergence

and Coordination between Government Schemes

When it designs and implements development

projects, the Bonkati gram panchayat uses funds and resources from NREGS and

other government income generation schemes. This convergence is an important

factor in the success of the projects it undertakes. In most of the land development,

pond re-excavation, horticulture, and kitchen garden projects, and for

afforestation on the river and pond embankments in Bonkati, the panchayat pools

resources from the NREGS and the Hariyali programme. Active participation of

SHGs in the attempt to take the projects beyond short-term wage-income

generation is also a remarkable feature of NREGS implementaion in this block.

In the projects on land development and pond

re-excavation, the funds for labour and material costs are drawn from NREGS as

well as the Hariyali programme. When the land is handed over to SHGs for

planting trees and other crops, saplings and financial assistance are provided

to the beneficiaries through the Hariyali programme. Generally 1,200 to 1,500

trees are provided per acre under this scheme in Bonkati. The Hariyali

programme also meets the labour and material input costs of maintaining the

plantations and gardens, for a maximum of three years.

Funds from NREGS and the Pradhan Mantri Gram

Sadak Yojana are brought together in the implementation of road construction

projects in Bonkati.

Such convergence and coordination between

different government schemes and SHGs broadens the scope of the projects and

allows better utilization of funds. Land and water-body development through

NREGS and Hariyali, and leasing out land, ponds, and embankments to groups of

workers and cultivators organized into SHGs, are practices that have the

potential to usher in a second wave of land reform in the State, bringing in hitherto

uncultivated land under cultivation, and introducing forms of mutual aid and

group farming.

Jean Dreze has recently expressed concern over the emphasis on what he terms the “convergence mantra” and other developments in the implementation of development schemes, including NREGS, in the country. According to him, these developments will encourage vested interests while workers’ interests will be compromised.10 The case of Bonkati shows that, in certain circumstances, convergence can improve the implementation of NREGS without compromising workers’ interests. What matters is the class and social structure of the implementing body that determines the policy choices and their implementation.

Role of the Gram Unnayan Samiti

A large part of the credit for the successful implementation of NREGS and other schemes in Kanksa block, according to Arun Karfa, nirman sahayak of Kanksa block, must go to the gram unnayan samitis for their proactive intervention in development programmes. He stated that the gram unnayan samiti of each gram sansad in each gram panchayat in Kanksa meticulously prepares an action plan at the beginning of each year, and supplements these plans throughout the year.11 The plans specify a shelf of employment generation projects. This set of innovative and feasible projects created by the gram unnayan samitis is the backbone of the NREGS programme in the region. Arun Karfa emphasized that although NREGS is a demand-driven programme in which employment has to be created on demand, it would have not been possible to provide employment on demand without anticipatory planning by the gram unnayan samitis.

To summarize, the success of the NREGS work undertaken in Bonkati lies in the achievement of three goals: short-term income generation through wage employment, medium-term income generation in agricultural self-employment, and long-term asset creation.

Keywords: National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme, West Bengal, rural development, employment, panchayat.

Acknowledgments: I thank Sumit Bhaduri of the Foundation for Agrarian Studies for research assistance. I am grateful to Rajib Gupta of Bonkati gram panchayat NREGS cell, Arun Karfa of Kanksa block NREGS cell, and officials of Bonkati gram panchayat for their kind cooperation. I am grateful to V. K. Ramachandran for comments and advice.

Notes

1 See Dreze and Oldiges (2007). Also see, for example, Singh (2009), Tiwari (2010), and Thakur (2009). Pranab Mukherjee was quoted as describing West Bengal as being “among the worst performers in NREGA” (PTI 2009). Anindya Sen, who presents no further evidence, declares the scheme in West Bengal to be a “flop” (Economic Times 2010a).

2 The gram panchayat is a village-level body that constitutes the third and lowest tier in the three-tier, decentralized system of local-level government in India. A gram panchayat may consist of one or more villages. Mouza is a revenue village in West Bengal.

3 The Chief Minister of West Bengal has been reported as having stated that the Government of India had not released the funds to which the State is entitled under NREGA (Dutta 2010).

4 Although more than 100 days of employment were generated per household, in the block’s official report to the Ministry of Rural Development an average of 94 person-days per household was reported, since the maximum number of days to which a household is entitled is 100, under the Act.

5 The gram unnayan samiti or village development council is an integral part of the panchayati raj system in West Bengal. It is an executive committee at the gram sansad level, and is constituted by members of the panchayat, opposition parties, representatives of SHGs and NGOs, and other important members of the gram sansad.

7 Kharif crops are sown in the monsoon and harvested in autumn, and rabi crops are planted in winter. Three crops of paddy are grown in West Bengal: aman, aus and boro. Aman is the main paddy crop. Aman and aus are both kharif crops with some overlap in their crop cycle, and boro is a crop harvested in the summer. The shares of aman, aus, and boro in the total area under paddy cultivation were 75 per cent, 5 per cent and 20 per cent, respectively, in 2006–07 (Government of West Bengal 2008).

8 The Hariyali programme is a part of the Integrated Watershed Management Programme of the Department of Land Resources, Ministry of Rural Development. The programme was begun in 2003.

10 See Economic Times (2010b).

11 The gram panchayat consists of gram sansads or rural electoral wards. Each gram sansad has an elected panchayat representative/member.

References

| Dreze, Jean, and Oldiges, Christian (2007), “How is NREGA doing?” paper presented at the International Seminar on “Revisiting the Poverty Issue: Measurement, Identification and Eradication Strategies,” 20–22 July 2007, A. N. Sinha Institute of Social Sciences, Patna; available at www.ansiss.org/seminar200707.aspx, viewed on 1 March 2010. | |

| Dutta, Ananya (2010), “Centre Has Abandoned the Farmer,” The Hindu, 1 September, http://www.hindu.com/2010/09/01/stories/2010090161320300.htm, viewed on 17 September 2010. | |

| Government of India (2010), Letter to the Principal Secretaries of States, No. M-12011/2/2008-NREGA(P), 21 January, http://nrega.nic.in/NREGAMela/MGNREGA_Awards.pdf, viewed on 1 March 2010. | |

| Government of West Bengal (2009), Implementation of the National Rural Employment Guarantee Act, 2005 in West Bengal during the year 2008–09, Report submitted to the State Legislative Assembly, http://wbprd.gov.in/html/aboutus/AASR2008-09.pdf, viewed on 1 March 2010. | |

| Government of West Bengal (2008), Economic Review 2007–08, Kolkata. |

News Articles

| Economic Times (2010a), “It’s Time to Cash in,” Planet East, Kolkata, 8 March. | |

| Economic Times (2010b), “Workers’ Interest Takes a Backseat,” Planet East, 8 March. | |

| PTI (2009), “West Bengal among Worst Performers in NREGA: Pranab,” Business Standard, 31 December. | |

| Singh, S. S. (2009), “No Pause to Bengal Slide in NREGA Implementation,” Indian Express, 18 December. | |

| Thakur, P. (2009), “Sonia’s Criticism of NREGA in Bengal Based on CAG Reports,” Times of India, 29 April. | |

| Tiwari, R., and Manoj, C. G. (2010), “NREGA: Red Marks for West Bengal and Kerala,” Indian Express, 3 February. |