ARCHIVE

Vol. 13, No. 2

JULY-DECEMBER, 2023

Editorial

Research Articles

Tribute

Book Reviews

Review Article

Changing Rural Labour Markets in India

Evidence from a Village in Southern Karnataka

*Independent researcher, satheeshabannur@gmail.com.

https://doi.org/10.25003/RAS.13.02.0003

Abstract: This paper examines changes in rural occupations in a south Indian village, Alabujanahalli in Karnataka, based on household surveys conducted in 2008-9 and 2018-19. While agriculture and allied activities continue to be the major source of livelihood for workers in the village, there are clear signs of diversification towards the non-farm sector, especially as younger workers get absorbed into regular jobs. Factors contributing to this diversification of employment include the expansion of education, the village’s proximity to the city of Bengaluru and to other urban areas, and uncertainty of incomes from cultivation. At the same time, the wage rates for casual workers in agriculture in Alabujanahalli were lower than the corresponding average figures for Karnataka and India, particularly for women. The factors that have depressed wage rates in the village include the high level of control that farmers manage to exert over labour, the poor implementation of the rural employment guarantee scheme, and the migration into the village of agricultural workers.

Keywords: Rural labour markets, agriculture, non-farm diversification, village study, Karnataka, India.

Introduction

This note examines changes in the rural labour market, in particular changes in the nature and patterns of employment and wages in rural India. It is based on a case study of Alabujanahalli, a village located in the Mandya district of southern Karnataka. A survey of Alabujanahalli was conducted by the Foundation for Agrarian Studies (FAS) in 2008–09, and a re-survey was conducted by the author ten years later, in 2018–19.

The diversification of employment away from agriculture has been an integral feature of economic development across countries of the world. In India, as late as 2017–18, 44.2 per cent of the workforce (or 206 million out of a total of 470 million) were employed in agriculture (GoI 2019). However, in recent years, especially between 2004–05 and 2011–12, there has been a rapid movement of the rural workforce out of agriculture. The faster movement of the workforce away from agriculture during this period was also associated with the growth of agricultural wages and incomes (Chand and Srivastava 2014; Thomas and Jayesh 2016). Nevertheless, the diversification process slowed down after 2012, as there was a significant decline in the growth of non-farm employment (Thomas 2020; Basole et al. 2019). This period was also characterised by a slowdown in agricultural incomes in India (Thomas and Satheesha 2021).

The labour market changes witnessed in India are not uniform across States (Satheesha 2023). According to data from the Periodic Labour Force Survey (PLFS), Karnataka is more agrarian than other South Indian States, with an overwhelming share of the rural workforce dependent on agriculture for their livelihood (67.2 per cent in 2017–18). In terms of rural wages and other indicators of development, Karnataka performs poorly as compared to the other south Indian States, in particular Tamil Nadu and Kerala (Thomas and Satheesha 2017).

The changes in the rural labour market referred to above are based on secondary data sources, especially labour force surveys. However, these data sources substantially under-report the land held by households, and underestimate women’s work and wage employment (Ramachandran 1990; Dhar 2012; Swaminathan 2020; and Vijayamba 2022). Given the limitations of secondary data sources, it is important to have village studies to get a deeper understanding of labour market changes in rural India. This note examines labour market transformation at the village level using data from primary surveys.

Field Survey

The 2008–09 survey1 by FAS of Alabujanahalli covered 243 households and collected detailed information on agricultural production and allied activities and costs, land holdings, tenancy, employment status, incomes and earnings, asset ownership, household amenities, and indebtedness. The re-survey of the village carried out by me in 2018–19 collected information related to demography, employment, and operational holdings for all households resident in the village (261 households). Of these 261 households, 102 households were selected for a detailed survey using proportionate random sampling based on size-class of operational holding, caste, non-farm employment, and migration-related information. Details of land ownership, agricultural production, employment (including wages and income), and asset information were collected from the sampled households.

All the statistics presented in this paper, unless otherwise specified, are based on the census data. The estimates of workers are based on persons’ primary occupation, as reported by the respondents in the survey.

Description of the Village

Alabujanahalli is largely agricultural and receives water from canals that are linked to the Cauvery River. According to the 2008–09 survey, the 243 households in Alabujanahalli owned 639 acres of land, of which 83 per cent was cultivated, mainly with sugarcane, paddy, and finger millet. Nearly 95 per cent of the cultivable land in the village was irrigated (Swaminathan and Das 2017; Modak 2018). Apart from crop production, animal husbandry and sericulture were other important economic activities in the village.

An important feature of Alabujanahalli is its proximity to semi-urban towns and large cities. The nearest town is K. M. Doddi, 1.5 km away. The nearest railway station is located at a distance of 15 kilometres, in Maddur. Mandya town and Bengaluru city are situated at a distance of 25 kilometres and 95 kilometres, from the village.

In 2018–19, households in the Backward Class category accounted for 88.2 per cent of the total population. Among the households in the Backward Class category, a major section belonged to the Vokkaliga caste. Vokkaliga households accounted for more than 75 per cent of all households, and owned more than 90 per cent of the village agricultural land. The other caste groups that fell within the category of Backward Classes were Besthar, Madivala, Thigala, Lingayat, and Barber. These caste groups (other than Lingayats) are at the bottom of the village’s economic hierarchy. The Scheduled Castes or Adi Karnataka comprised 11.3 per cent of the total population of the village in 2018–19.

Labour Market Changes in Alabujanahalli: 2008–09 to 2018–19

Population and Workforce

The survey of 2018–19 covered 1,194 persons in Alabujanahalli. Out of the total population, 568 persons (423 males and 145 females) were employed, and 625 persons (178 males and 447 females) were outside the labour force.2 Students and persons attending to domestic duties constituted an important section of the population that was not part of the labour force. Interestingly, the proportion of students in the total population was higher among females than among males in the village. In 2018–19, the proportion of students (of all ages) among females and males was 21.9 per cent and 18.3 per cent. At the time of the 2018–19 primary survey, 40.6 per cent of the women in Alabujanahalli reported their main activity status as “attending to domestic duties” (Table 1).

Table 1 Distribution of population in Alabujanahalli by activity status in numbers and per cent

| 2008–09 | 2018–19 | |||||||

| Males | Females | Males | Females | |||||

| Number | Per cent | Number | Per cent | Number | Per cent | Number | Per cent | |

| 1. Workers | 404 | 65.2 | 152 | 24.7 | 423 | 70.4 | 145 | 24.5 |

| 1.1 Agriculture | 329 | 53.1 | 124 | 20.2 | 286 | 47.6 | 95 | 16.0 |

| 1.1.1 Self-employed | 272 | 43.9 | 63 | 10.2 | 243 | 40.4 | 54 | 9.1 |

| 1.1.2 Casual labour | 57 | 9.2 | 61 | 9.9 | 43 | 7.2 | 41 | 6.9 |

| 1.2 Non-agriculture | 75 | 12.1 | 28 | 4.6 | 137 | 22.8 | 50 | 8.4 |

| 1.2.1 Self-employed | 30 | 4.8 | 9 | 1.5 | 35 | 5.8 | 8 | 1.3 |

| 1.2.2 Casual labour | 6 | 1.0 | 4 | 0.7 | 7 | 1.2 | 4 | 0.7 |

| 1.2.3 Regular wage/salaried | 39 | 6.3 | 15 | 2.4 | 95 | 15.8 | 38 | 6.4 |

| 2. Unemployed | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.2 |

| 3. In labour force (1+2) | 404 | 65.2 | 152 | 24.7 | 423 | 70.2 | 146 | 24.6 |

| 4. Not in labour force | 216 | 34.8 | 463 | 75.3 | 178 | 29.6 | 447 | 75.4 |

| 4.1 Students | 155 | 25.0 | 150 | 24.4 | 110 | 18.3 | 130 | 21.9 |

| 4.2 Attending to domestic work | 1 | 0.2 | 257 | 41.8 | 1 | 0.2 | 241 | 40.6 |

| 4.3 Too old to work | 11 | 1.8 | 21 | 3.4 | 30 | 5.0 | 48 | 8.1 |

| 4.4 Other | 49 | 7.9 | 35 | 5.7 | 37 | 6.2 | 28 | 4.7 |

| All persons | 620 | 100 | 615 | 100 | 601 | 100 | 593 | 100 |

Source: Survey conducted by FAS in 2009 and author’s survey in 2019.

We estimated the proportion of workers (persons who were employed) in the total population, or the workforce participation rate (WPR), based on the primary occupation, as reported by the respondents in the survey. In 2018–19, the WPR (for all ages) was 70.4 per cent for men and 24.5 per cent for women in Alabujanahalli (Table 1).

Structure of and Changes in Employment

Agricultural employment

In Alabujanahalli, the proportion of workers who reported agriculture as their primary occupation was 81.5 per cent in 2008–09, which declined to 67.1 per cent by 2018–19. It should be noted that in 2008–09, income from agriculture contributed only 58.0 per cent of the average annual household income in the village (Swaminathan and Das 2017) even while 81.5 per cent of the workforce had reported agriculture as their primary occupation. While we do not have data on household incomes for 2018–19, it is likely that agriculture’s share in household income was substantially less than the sector’s share in the workforce. In other words, agriculture was likely to have contributed less than half of the average household incomes in Alabujanahalli by the late 2010s.

The diversification of occupations away from agriculture during the decade after 2008–09 was faster among younger women and men than among the older age-groups (Appendix Tables 1 and 2). Various other studies based on field surveys and secondary data have also observed the exit of young workers from agriculture in rural India (Jodhka 2014; Himanshu et al. 2016; Satheesha 2023; and Swaminathan et al. 2023).

In 2018–19, more than half (52.3 per cent) of all workers in Alabujanahalli reported that they were self-employed in agriculture (mainly as cultivators). The proportion of workers who were self-employed in agriculture was higher among men than among women, while the proportion of casually employed in agriculture was higher among women than among men (see Table 2). Between 2008–09 and 2018–19, there was a decline in the numbers of workers who reported self-employment as well as casual employment in agriculture. This decline occurred for both men and women, as well as for workers belonging to all caste groups (except Madivalas) (see Tables 2 and 3).

Table 2 Distribution of workers by primary occupation, by sex, Alabujanahalli in per cent

| 2008–09 | 2018–19 | |||||

| Males | Females | Persons | Males | Females | Persons | |

| 1. Agriculture | 81.4 | 81.5 | 81.5 | 67.6 | 65.5 | 67.1 |

| 1.1 Self-employed | 67.3 | 41.4 | 60.3 | 57.4 | 37.2 | 52.3 |

| 1.2 Casual labour | 14.1 | 40.1 | 21.2 | 10.2 | 28.3 | 14.8 |

| 2. Non-agriculture | 18.6 | 18.4 | 18.5 | 32.4 | 34.5 | 32.9 |

| 2.1 Self-employed | 7.4 | 5.9 | 7.0 | 8.3 | 5.5 | 7.6 |

| 2.2 Casual labour | 1.5 | 2.6 | 1.8 | 1.7 | 2.8 | 1.9 |

| 2.3 Regular wage/salaried | 9.7 | 9.9 | 9.7 | 22.5 | 26.2 | 23.4 |

| All workers (in per cent) (1+2) | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| All workers (in numbers) | 404 | 152 | 556 | 423 | 145 | 568 |

Source: Survey conducted by FAS in 2009 and author’s survey in 2019.

Table 3 Distribution of workers by primary occupation across different caste groups, Alabujanahalli in per cent

| 2008–09 | 2018–19 | |||||||

| Vokkaliga | Besthar | Madivala | SC | Vokkaliga | Besthar | Madivala | SC | |

| 1. Agriculture | 85.5 | 90.0 | 35.3 | 79.5 | 68.9 | 70.7 | 47.6 | 61.3 |

| 1.1 Self-employed | 76.4 | 30.0 | 8.8 | 37.4 | 62.2 | 34.1 | 19.0 | 20.0 |

| 1.2 Casual labour | 9.1 | 60.0 | 26.5 | 42.2 | 6.7 | 36.6 | 28.6 | 41.3 |

| 2. Non-agriculture | 14.5 | 10.0 | 64.7 | 20.5 | 31.2 | 29.3 | 52.4 | 38.7 |

| 2.1 Self-employed | 4.8 | 2.5 | 47.1 | 0.0 | 6.5 | 12.2 | 33.3 | 4.0 |

| 2.2 Casual labour | 0.5 | 0.0 | 2.9 | 7.2 | 1.0 | 4.9 | 4.8 | 4.0 |

| 2.3 Regular wage/salaried | 9.1 | 7.5 | 14.7 | 13.3 | 23.7 | 12.2 | 14.3 | 30.7 |

| All workers (in per cent) (1+2) | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| All workers (in numbers) | 373 | 40 | 34 | 83 | 418 | 41 | 21 | 75 |

Source: Survey conducted by FAS in 2009 and author’s survey in 2019.

It is notable that despite the decline in agricultural employment, nearly two-thirds of all workers in Alabujanahalli reported agriculture as their primary occupation in 2018–19. This is notwithstanding the proximity of the village to semi-urban towns and large cities. Favourable historical conditions, in particular the extension of irrigation after the construction of the Krishnarajasagara dam across the Cauvery River in the 1930s, the shift in cropping pattern from cereal crops to sugarcane, and well-established and relatively stable markets for agricultural products have contributed to agricultural prosperity and to the continued dependence on agriculture as a source of livelihood in Alabujanahalli.3

In addition, the integration of Alabujanahalli with the regional economy opened a number of supplementary income-earning opportunities for farmers, which included sericulture and animal husbandry. Some of the well-to-do cultivator households were engaged in trading and businesses, and a few of them earned rental incomes from the houses and commercial buildings they owned in K.M. Doddi and other nearby towns. Such incomes from sources other than cultivation helped farmers mitigate the instability in agricultural incomes.

At the same time, a section of workers from disadvantaged castes continued as agricultural labourers with limited opportunities to diversify. This included workers from the Thigala and Madivala castes, and older Scheduled Caste workers.

Non-farm diversification

A distinctive aspect of the diversification of employment towards the non-farm sector in Alabujanahalli is the growth of regular jobs.4 In 2018–19, there were 95 men and 38 women in Alabujanahalli who were in regular salaried jobs. This was more than twice the number of persons who had regular jobs in the village in 2008–09 (39 men and 15 women).

Substantial numbers of women and Scheduled Caste workers were in regular jobs. In 2018–19, the proportions of workers with regular jobs were 26.2 per cent and 30.7 per cent respectively among women and the Scheduled Castes (see Tables 2 and 3). During the 2010s, there was a big increase in the number of women in better-paid jobs, including those employed as teachers, health workers, and professionals in multinational companies. In 2008–09, there were only three women in Alabujanahalli who were employed in better-paid jobs, but by 2018–19 this number increased to 28, and they accounted for 62.2 per cent of all female non-farm workers in the village (see Table 4).

Table 4 Distribution of workers in various non-farm activities, Alabujanahalli in numbers

| 2008–09 | 2018–19 | |||

| Males | Females | Males | Females | |

| 1. Jobs requiring moderate to high skills | 20 | 3 | 38 | 28 |

| 1.1 Teaching and related activities | 5 | 3 | 5 | 7 |

| 1.2 Hospital and health-related activities | 1 | 0 | 4 | 3 |

| 1.3 Banking/finance | 1 | 0 | 4 | 1 |

| 1.4 Corporate employees (MNCs) | 3 | 0 | 11 | 10 |

| 1.5 Accountants/clerks | 4 | 0 | 6 | 4 |

| 1.6 Other | 6 | 0 | 8 | 3 |

| 2. Less-skilled jobs | 16 | 8 | 33 | 8 |

| 2.1 Attenders/cashiers/anganwadi workers | 4 | 2 | 2 | 4 |

| 2.2 Helpers in restaurant/bar/shop/school | 5 | 6 | 12 | 3 |

| 2.3 Security guards | 0 | 0 | 3 | 1 |

| 2.4 Bus conductors/drivers and other transport -related workers | 7 | 0 | 16 | 0 |

| 3. Business/shop owners | 17 | 0 | 22 | 1 |

| 4. Trade workers and operators (electricians/linesman) | 2 | 0 | 7 | 1 |

| 5. Manufacturing | 7 | 9 | 28 | 6 |

| 5.1 Sugarcane factory workers | 4 | 0 | 8 | 0 |

| 5.2 Fitters/mechanics/packing, etc. | 3 | 0 | 19 | 3 |

| 5.3 Garment/tailoring | 0 | 9 | 1 | 3 |

| 6. Manual occupations (laundry/construction) | 13 | 8 | 9 | 6 |

| All non-farm workers | 75 | 28 | 137 | 50 |

| All workers | 404 | 152 | 423 | 145 |

| Non-farm workers as per cent of all workers | 18.6 | 18.4 | 32.4 | 34.5 |

| Regular workers as per cent of all non-farm workers | 52.0 | 53.6 | 69.3 | 76.0 |

| Jobs requiring moderate to high skills as per cent of all non-farm workers | 28.0 | 17.9 | 29.2 | 62.2 |

Source: Survey conducted by FAS in 2009 and author’s survey in 2019.

Bengaluru was the location of employment for a majority of those who found non-farm jobs in the decade after 2008–09. There were also persons who worked in nearby towns, and commuted between their places of work and the village on a daily basis. These persons were typically engaged in low-paying jobs in sales, trading, and other service sectors. In 2018–19, in Alabujanahalli, out of 187 non-farm workers, 88 were migrants and 79 were commuters. Some of the workers (seven workers) opted to commute daily to Bengaluru because of better rail and road connectivity.

The younger workers from the Vokkaliga community were successful in securing jobs in the services sector that were accessed largely through migration, with many of them working as professionals in Bengaluru. In 2008–09, out of 373 Vokkaliga workers, there were 54 non-farm workers including 20 employed in better-paying and relatively high-skilled jobs. By 2018–19, there were a total of 418 Vokkaliga workers, including 130 non-farm workers, among whom 58 were employed as relatively high-skilled professionals (Table 5).

Table 5 Distribution of workers by caste and sector of employment in numbers

| 2008–09 | 2018–19 | |||||||||

| Vokkaliga | Besthar | Madivala | Scheduled Caste | All | Vokkaliga | Besthar | Madivala | Scheduled Caste | All | |

| 1. Jobs requiring moderate to high skills | 20 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 23 | 58 | 3 | 0 | 4 | 66 |

| 1.1 Teaching and related activities | 7 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 9 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 12 |

| 1.2 Hospital and health-related activities | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7 |

| 1.3 Banking/finance | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 |

| 1.4 Corporate employees (MNCs) | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 20 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 21 |

| 1.5. Accountants/clerks | 3 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 4 | 9 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 10 |

| 1.6 Other professionals | 5 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 6 | 8 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 11 |

| 2. Less-skilled jobs | 11 | 1 | 4 | 7 | 24 | 23 | 2 | 0 | 16 | 41 |

| 2.1 Attenders/peons/anganwadi workers | 5 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 6 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 6 |

| 2.2 Helpers and assistants in restaurants/shops/schools | 4 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 11 | 9 | 1 | 0 | 5 | 15 |

| 2.3 Security guards | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 4 |

| 2.4 Bus conductors/drivers and other Transport-related workers | 2 | 0 | 2 | 3 | 7 | 9 | 1 | 0 | 6 | 16 |

| 3. Business/shop owners | 13 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 17 | 19 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 23 |

| 4. Trade workers and operators (electricians/linesmen) | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 8 |

| 5. Manufacturing | 7 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 16 | 25 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 34 |

| 5.1 Sugarcane factory workers | 3 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 4 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 8 |

| 5.2 Fitter/mechanic/packing, etc. | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 3 | 14 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 22 |

| 5.3 Garment/tailoring | 4 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 9 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 |

| 6. Manual labour/elementary occupations | 2 | 0 | 14 | 4 | 21 | 2 | 4 | 7 | 2 | 15 |

| 6.1 Laundry | 0 | 0 | 14 | 0 | 14 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 6 |

| 6.2 Construction | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| 6.3 Other | 1 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 6 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 7 |

| All non-farm workers | 54 | 4 | 22 | 17 | 103 | 130 | 12 | 10 | 29 | 187 |

| All regular workers | 34 | 3 | 5 | 11 | 54 | 99 | 5 | 3 | 23 | 134 |

| All farm-workers | 319 | 36 | 12 | 66 | 453 | 288 | 29 | 10 | 46 | 381 |

| All workers | 373 | 40 | 34 | 83 | 556 | 418 | 41 | 20 | 75 | 568 |

Source: Survey conducted by FAS in 2009 and author’s survey in 2019

It is significant that Scheduled Castes workers have been successful in reducing their dependence on agriculture and in securing regular jobs. In 2018–19, there were 23 regular workers belonging to the Scheduled Castes, although it may be noted that only four of these workers were in better-paying jobs. The rest were engaged in low-paying jobs in the services sector, including as helpers in restaurants, bars, shops, and schools, and as security guards (Table 5). Besthars and Madivalas were not as successful in diversifying their employment towards the non-farm sector.

Another important aspect of non-farm diversification in Alabujanahalli was a rise in manufacturing employment for men, particularly in factories located in Bengaluru. There were only seven men in the village who were employed in the manufacturing sector in 2008–09, but that number increased to 28 by 2018–19 (Table 4). It should be noted that the NSS and PLFS data show a general fall in manufacturing employment after 2011–12 in India as a whole and across most Indian States (Mehrotra and Parida 2021; Thomas 2020). At the same time, there was a decline in female employment in the manufacturing sector in Alabujanahalli over the decade, which was mainly due to a fall in jobs in garment-making and tailoring. The process of industrial restructuring is identified as a possible reason for the recent decline in women’s employment in the garment industry in India (Johny 2022).

There has been a decline in the number of workers engaged in unskilled and low-paying manual jobs (mainly laundry work) in Alabujanahalli between 2008–09 and 2018–19 (see Table 4). Over the decade, some of the Madivala households, which traditionally had been engaged in laundry work, abandoned this occupation and permanently migrated out of the village in search of better economic opportunities.

Factors that aided non-farm diversification in Alabujanahalli

The expansion of education, in particular higher education, has played a key role in providing access to non-farm employment opportunities. Between 2008–09 and 2018–19, there was a marked improvement in the levels of education among the younger age cohorts in Alabujanahalli, especially among females. In 2018–19, 42.9 per cent of all female workers in Alabujanahalli in the age-group of 25 to 34 years had completed graduation or above, which was higher than the corresponding proportion for male workers (32.5 per cent). It was also a big jump from the proportion of female workers aged 25–34 years and educated at least till graduation in 2008–09 (12.1 per cent) (see Appendix Tables 3 and 4). The achievements of female workers with respect to education explain their success in securing better-paying jobs in the services sector by 2018–19.

The expansion in higher education in Alabujanahalli was driven by educational institutions located in the nearby towns. The majority of students from Alabujanahalli pursued their degree courses in Bharathi College (aided college) in K.M. Doddi, which comes under the Bharathi Education Trust (BET) founded by G. Madegowda in 1962.

Workers from all caste groups other than Madivala registered improvement in educational achievements. For example, the proportion of Scheduled Caste workers who completed higher secondary or higher levels of education was only 10.8 per cent in 2008–09, and the proportion rose to 29.3 per cent by 2018–19 (Table 6). However, this proportion is still relatively low.

Table 6 Distribution of workforce by caste and education levels, Alabujanahalli in per cent

| 2008–09 | ||||

| Vokkaliga | Besthar | Madivala | SC | |

| Not literate | 40.2 | 62.5 | 73.5 | 60.2 |

| Literate and up to primary school | 3.5 | 0.0 | 2.9 | 3.6 |

| Middle school | 12.6 | 12.5 | 8.8 | 9.6 |

| Secondary school | 19.6 | 15.0 | 14.7 | 15.7 |

| Higher secondary | 10.5 | 7.5 | 2.9 | 6.0 |

| Diploma/ITI | 1.9 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 3.6 |

| Graduation | 10.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.2 |

| Post-graduation and above | 1.3 | 2.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| All workers (in per cent) | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| All workers (in numbers) | 373 | 40 | 34 | 83 |

| 2018–19 | ||||

| Not literate | 26.1 | 41.5 | 76.2 | 41.3 |

| Literate and up to primary school | 1.2 | 2.4 | 4.8 | 2.7 |

| Middle school | 7.9 | 14.6 | 4.8 | 5.3 |

| Secondary school | 22.5 | 26.8 | 9.5 | 21.3 |

| Higher secondary | 15.1 | 4.9 | 4.8 | 13.3 |

| Diploma/ITI | 6.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 2.7 |

| Graduation | 17.0 | 7.3 | 0.0 | 9.3 |

| Post-graduation and above | 3.8 | 2.4 | 0.0 | 4.0 |

| All workers (in per cent) | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| All workers (in numbers) | 418 | 41 | 20 | 75 |

Source: Survey conducted by FAS in 2009 and author’s survey in 2019.

Another important aspect of the expansion in higher education in Alabujanahalli was a rise in the number of diploma/ITI holders among male workers, which enabled them to find jobs in the manufacturing sector mostly in Bengaluru.

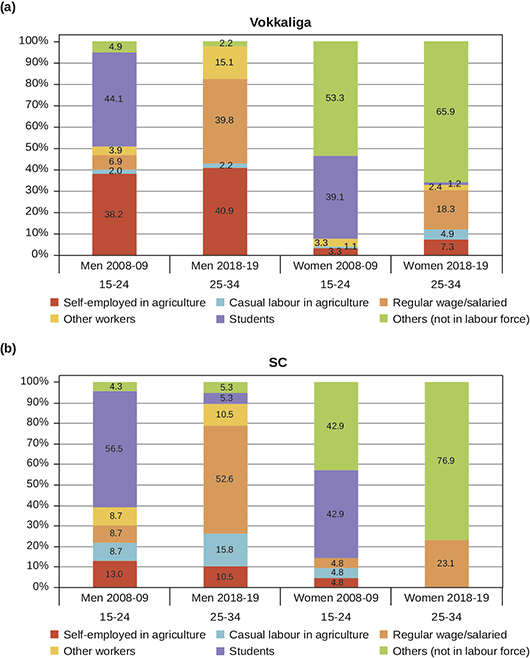

Next, using cohort-based approach, we have tracked the activity status of individuals aged 15–24 years in 2008–09 and 25–34 years in 2018–19. The comparison was made for men and women belonging to the Scheduled Castes and the Vokkaliga caste.

In 2008–09, 44.1 per cent of Vokkaliga men and 56.5 per cent of Scheduled Caste men in the age-group of 15–24 in Alabujanahalli were pursuing higher education. In 2018–19, 52.6 per cent of the Scheduled Caste men in the age group of 25–34 had regular jobs and corresponding figure for Vokkaliga men was 39.8 per cent. It appears that the relatively high educational achievements of the 15–24 year-olds among the Scheduled Castes and Vokkaligas in 2008–09 translated into regular employment opportunities for these groups as they entered the job market in the 2010s (see Figures 1a and b).

Figure 1 Distribution of activity status of Vokkaliga and Scheduled Caste cohorts, age-group 15–24 in 2008–9 and 25–34 in 2018–19, Alabujanahalli in per cent

Source: Survey conducted by FAS in 2009 and author’s survey in 2019.

However, educated women were not as successful in securing regular jobs. In 2008–09, nearly 40 per cent of women aged 15 to 24 years among the Scheduled Castes and Vokkaligas in the village were students. But in 2018–19, less than 25 per cent of women aged 25 to 34 years belonging to the Vokkaliga and the SC communities were in regular jobs (see Figures 1a and b).

The uncertainty of incomes from agriculture might have urged some of the younger workers in Alabujanahalli to seek non-agricultural opportunities. While the sugarcane farmers could expect to receive relatively high incomes given the high yields and minimum support prices, they still had to wait four to 12 months after the delivery of the produce to receive payments from the sugarcane factories which purchased the produce. Further, the fast growth of sugarcane output between 2008–09 and 2018–19 mainly benefited only the rich farmers in Alabujanahalli, who in fact, devoted a large part of their land holdings to sugarcane cultivation (Table 7).5

Table 7 Average yield and gross value of output (GVO) of major crops, Alabujanahalli

| 2008–09 | 2018–19 | 2018–19/ 2008–09 | ||

| Average yield of major crops (kg per acre) | ||||

| Sugarcane (planted) | 40000 | 52000 | 1.3 | |

| Sugarcane (ratoon) | 34135 | 36240 | 1.1 | |

| Paddy | 1600 | 1865 | 1.2 | |

| Finger millet | 1500 | 1308 | 0.9 | |

| Average gross value of output (Rs per acre) | ||||

| Sugarcane (planted) | 44000 | 134934 | 3.1 | |

| Sugarcane (ratoon) | 38600 | 93463 | 2.4 | |

| Paddy | 16365 | 28852 | 1.8 | |

| Finger millet | 12750 | 34008 | 2.7 | |

| Consumer Price Index for Rural Labour (CPI-RL) for Karnataka (at 2008–09 prices) | 100 | 222 | 2.2 | |

| Average real gross value of output (Rs per acre) (at 2008–09 prices) | ||||

| Sugarcane (planted) | 44000 | 60781 | 1.4 | |

| Sugarcane (ratoon) | 38600 | 42100 | 1.1 | |

| Paddy | 16365 | 12996 | 0.8 | |

| Finger millet | 12750 | 15319 | 1.2 | |

Source: Survey conducted by FAS in 2009 and author’s sample survey in 2019.

Households with smaller holdings allocated a larger share of their land to the cultivation of cereals. It is possible that they experienced income losses as the real gross value of output of paddy declined between 2008–09 and 2018–19 (Table 7). During this period, there was a rise in the share of cultivators who reported supplementary sources of income. As stated by the respondents, the dependence on supplementary sources of income, particularly animal husbandry and sericulture, was due to the uncertainty of returns from cultivation.

A major issue faced by paddy cultivators in Alabujanahalli is the shortage of water available through canal irrigation. A number of farmers had kept their land -- especially land under paddy cultivation -- fallow during the summer season in 2018–19, because of the non-availability of canal water. The cultivation of sugarcane was not affected much by the water shortage because the majority of the farmers have private irrigation facilities for land under sugarcane.

Thirdly, the village’s proximity to semi-urban towns and cities with better road and rail networks helped young workers to access non-farm opportunities outside the village.

Agricultural Wages

The average daily (nominal) wage rates for casual agricultural labour in Alabujanahalli were Rs 264 for men and Rs 131 for women in 2018–19 (Table 8). These wage rates were lower than the figures for Karnataka and India, as reported in the official employment surveys. In 2017–18, the daily (nominal) wage rates for male and female casual workers in agriculture in Karnataka were Rs 249 and Rs 149, respectively, while the corresponding national averages were Rs 229 and Rs 163 (GoI 2019).

Table 8 Wages for casual labour in agriculture, Alabujanahalli

| 2008–09 | 2018–19 | |||

| Males | Females | Males | Females | |

| Nominal wage (Rs per day) | 113 | 51 | 264 | 131 |

| Real wage (Rs per day at 2008–09 prices) | 113 | 51 | 117 | 58 |

| Rice wage (kg/day) | 12.9 | – | 17.1 | – |

| Ragi wage (kg/day) | 14.4 | – | 10.2 | – |

Note: Nominal wage was deflated by using CPI-AL for Karnataka (2008–09 prices). The rice and ragi wages were calculated by dividing the nominal wage by the sale prices of rice and ragi in Alabujanahalli.

Source: Survey conducted by FAS in 2009 and author’s survey in 2019.

Real wages in agriculture were stagnant in Alabujanahalli over the decade. During the period 2008–09 to 2018–19, nominal wage rates for casual labour in agriculture increased on an average by two-and-a-half times in Alabujanahalli, while the Consumer Price Index for Agricultural Labour (CPI-AL) in Karnataka increased by more than two times (Table 8).

In Alabujanahalli, rice and ragi (finger millet) are the staple food, and I estimated the quantities of rice and ragi that could be purchased with the nominal wages received by a worker in a day (Table 8).

In 2008–09, the daily wage received by a male agricultural worker was sufficient to purchase 12.9 kg of rice or 14.4 kg of ragi. By 2018–19, the corresponding quantities were 17.1 kg of rice or 10.2 kg of ragi. Therefore, for male agricultural workers, the rice wage rate increased by 4 kg per day, while the ragi wage rate declined by 4.2 kg per day during this period. It may be noted that there was a large increase in the sale price of ragi over the decade.

Factors that may have contributed to depressed wage rates in Alabujanahalli are, first, the high level of control that farmers manage to exert over labour, secondly, the poor implementation of MGNREGA, and thirdly, in-migration of workers.

There were two cases of attached labour reported in the village. Both workers belonged to the Thigala caste. A worker gave the following account during an interview in 2018–19:

Six years ago, I borrowed money (Rs 1 lakh) from a rich farmer in the village to meet medical expenses. Since then, I have been working on his land. The employer (Vokkaliga) pays me Rs 300 per day, but from that wage, he deducts Rs 100 as interest. I want to look for other jobs in Bengaluru. However, the employer is not allowing me to move out of the village until I pay the full amount. There are many people like me in this village, but they don’t reveal [that they are attached labour].

Among households with at least one member of a household working under MGNREGA, the average days of employment was less than 40 days, much below the guaranteed 100 days of wage employment. The ineffective implementation of MGNREGA may have reduced the bargaining power of workers in wage negotiations. In general, the implementation of MGNREGA in Karnataka has been poor as compared to other Indian States (Usami and Rawal 2012; Pattenden 2017).

In Alabujanahalli, sugarcane factories brought in migrant workers from Bellary (a district in northern Karnataka) for labour-intensive tasks such as sugarcane harvesting.

Summary and Conclusions

This note examined changes in patterns of employment and wages in Alabujanahalli between 2008–09 and 2018–19.

Though agriculture and allied activities remained as the primary occupation for majority of the workforce in the village, the resurvey in 2018–19 showed strong signs of diversification of employment towards the non-farm sector, in particular among young and educated members of the workforce. A distinct feature of this labour market transformation is the role played by regular jobs in the non-agricultural sector. Vokkaliga workers succeeded in securing better-paying regular jobs in educational institutions, MNCs, and the manufacturing sector in Bengaluru, whereas most of the Scheduled Caste workers were employed in low-paying jobs (security guards, drivers, suppliers in bars, and sales workers in the textile industry) in nearby towns.

The expansion of education, in particular higher education, was a factor that enabled younger workers to get regular jobs in the non-farm sector. Our analysis of the activity status of the 15 to 24 year-olds in 2008–09 and 25 to 34 year-olds in 2018–19 shows that a high proportion of educated men among the Vokkaligas and the Scheduled Castes in the village were successful in securing regular jobs during the 2010s. A similar transition did not happen, however, in the case of women.

In addition, younger workers may have been pushed out of agriculture because of income uncertainty arising from cultivation. An important problem faced by the sugarcane farmers in the village is delays in payments from sugarcane factories. Meanwhile, the poorer farm households experienced a decline in income from rice cultivation between 2008–09 and 2018–19.

At the same time, a section of workers from disadvantaged social groups continued as agricultural labourers with stagnant real wages and some even remaining as attached workers. Better implementation of MGNREGA can improve the condition of such workers.

Acknowledgment: I thank Professor Jayan Jose Thomas, two anonymous reviewers, and Chinju Johny for helpful comments on the paper.

Notes

2 There were a number of persons surveyed who reported spending a major part of the year outside the village but were still considered as members of the village households because of their frequent visits to the village and their contributions to the family budget.

3 Epstein (1962) documents how the construction of a dam across the Cauvery River in the 1930s brought prosperity to Mandya, and the subsequent agricultural and economic development of the region.

4 According to our definition, a worker is in regular employment if she or he receives salaries or wages on a monthly basis rather than on a daily basis.

5 The rich farmers in the village had devoted more than 40 per cent of their land to the cultivation of sugarcane. At the same time, poor farmers in the village allocated 54 per cent of total cropped area for the cultivation of low-profit cereals such as paddy and finger millet (Swaminathan and Das 2017). Households fall into the “rich farmer” (peasant 1) category if the value of their household assets exceeds 5 million, while those classified as “poor farmer” (peasant 4) if the value of their household assets is below Rs 1 million (see Ramachandran 2017).

References

| Basole, A., Abraham, R., Idiculla, M., et al. (2019), State of Working India 2019, Centre for Sustainable Employment (CSE), Azim Premji University, Bengaluru. | |

| Chand, R., and Srivastava, S. (2014), “Changes in the Rural Labour Market and Their Implications for Agriculture,” Economic and Political Weekly, vol. 49, no. 10, pp. 47–54. | |

| Das, A., and Usami, Y. (2017), “Wage Rates in Rural India, 1998–99 to 2016–17,” Review of Agrarian Studies, vol. 7, no. 2, pp. 5–38. | |

| Dhar, N. S. (2012), “On Days of Employment of Rural Labour Households,” Review of Agrarian Studies, vol. 2, no. 2, pp. 106–15. | |

| Epstein, T. S. (1962), Economic Development and Social Change in South India, Manchester University Press, Manchester. | |

| Foundation for Agrarian Studies (n.d.), Survey Methods Toolbox, available at https://fas.org.in/repository/survey-methods-toolbox/, viewed on September 14, 2023. | |

| Government of India (GoI) (2019), Annual Report: Periodic Labour Force Survey 2017–18, National Statistical Office, Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation, New Delhi. | |

| Himanshu, Jha, P., and Gerry, R. (eds.) (2016), The Changing Village in India: Insights from Longitudinal Research, Oxford University Press, New Delhi. | |

| Jodhka, S. (2014), “Emergent Ruralities: Revisiting Village Life and Agrarian Change in Haryana,” Economic and Political Weekly, vol. 49, no. 26/27, pp. 5–17. | |

| Johny, C. (2022), “Female Employment in Indian Manufacturing: A study of the Garment Industry in Bangalore and the NCR Region,” unpublished PhD thesis, Indian Institute of Technology Delhi. | |

| Mehrotra, S., and Parida, J. K. (2021), “Stalled Structural Change Brings an Employment Crisis in India,” Indian Journal of Labour Economics, vol. 64, pp. 281–308. | |

| Modak, T. S. (2018), “From Public to Private Irrigation: Implications for Equity in Access to Water,” Review of Agrarian Studies, vol. 8, no. 1, pp. 28–64. | |

| Pattenden, J. (2017), Labour, State and Society in Rural India: A Class-Relational Approach, Social Science Press, New Delhi. | |

| Ramachandran, V. K. (1990), Wage Labour and Unfreedom in Agriculture: An Indian Case Study, Clarendon Press, Oxford. | |

| Ramachandran, V. K. (2017), “Socio-Economic Classes in the Three Villages,” in Swaminathan, Madhura, and Das, Arindam (eds.), Socio-economic Surveys of Three Villages in Karnataka: A Study of Agrarian Relations, Tulika Books, New Delhi. | |

| Satheesha, B. (2023), “Changing Rural Labour Markets in India: Evidence from Secondary Data and a Village in Karnataka,” unpublished PhD thesis, Indian Institute of Technology Delhi. | |

| Swaminathan, M. (2020), “Contemporary Features of Rural Workers in India with a Focus on Gender and Caste,” Indian Journal of Labour Economics, vol. 63, no. 1, pp. 67–79. | |

| Swaminathan, M., and Das, A. (eds.) (2017), Socio-economic Surveys of Three Villages in Karnataka: A Study of Agrarian Relations, Tulika Books, New Delhi. | |

| Swaminathan, M., Surjit, V. and Ramachandran, V. K. (eds.) 2023, Economic Change in the Lower Cauvery Delta: A Study of Palakurichi and Venmani, Tulika Books, New Delhi. | |

| Thomas, J. J. (2020), “Labour Market Changes in India, 2005–2018: Missing the Demographic Window of Opportunity?” Economic and Political Weekly, vol. 55, no. 34, pp. 57–63. | |

| Thomas, J. J., and Jayesh, M. P. (2016), “Changes in India’s Rural Labour Market in the 2000s: Evidence from the Census of India and the National Sample Survey,” Review of Agrarian Studies, vol. 6, no. 1, pp. 81–115. | |

| Thomas, J. J., and Satheesha, B. (2017), “Wages, Internal Migration and Labour Markets: An Analysis of Indian States,” Background paper for International Labour Organization (ILO), New Delhi. | |

| Thomas, J. J., and Satheesha, B. (2021), “Agriculture and Rural Labour Markets in India,” in Raj, S. N. Rajesh, and Singha, Komol (eds.), The Routledge Handbook of Post-Reform Indian Economy, Routledge, New York. | |

| Usami, Y., and Rawal, V. (2012), “Some Aspects of the Implementation of India’s Employment Guarantee,” Review of Agrarian Studies, vol. 2, no. 2, pp. 74–105. | |

| Vijayamba, R. (2022), “Women in Livestock Economy,” unpublished PhD thesis, Indian Statistical Institute, Bengaluru. |

Appendix

Appendix Table 1 Distribution of activity status of male population by different age-groups, Alabujanahalli in per cent

| 2008–09 | 2018–19 | |||||||||||

| 15–24 | 25–34 | 35–44 | 45–59 | 60+ | 15–59 | 15–24 | 25–34 | 35–44 | 45–59 | 60+ | 15–59 | |

| 1. Workers | 50.4 | 97.2 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 77.9 | 82.6 | 50.0 | 96.8 | 100.0 | 98.2 | 64.0 | 88.9 |

| 1.1 Agriculture | 36.9 | 67.9 | 82.6 | 95.2 | 73.5 | 65.9 | 23.8 | 41.9 | 69.8 | 82.5 | 62.8 | 56.0 |

| 1.1.1 Self-employed | 30.5 | 53.2 | 69.8 | 80.7 | 63.2 | 54.4 | 16.3 | 33.9 | 59.4 | 74.6 | 53.5 | 47.6 |

| 1.1.2 Casual labour | 6.4 | 14.7 | 12.8 | 14.5 | 10.3 | 11.5 | 7.5 | 8.1 | 10.4 | 7.9 | 9.3 | 8.5 |

| 1.2 Non-agriculture | 13.5 | 29.4 | 17.4 | 4.8 | 4.4 | 16.7 | 26.3 | 54.8 | 30.2 | 15.8 | 1.2 | 32.9 |

| 1.2.1 Self-employed | 3.5 | 11.0 | 9.3 | 2.4 | 2.9 | 6.4 | 7.5 | 12.1 | 7.3 | 4.4 | 1.2 | 8.0 |

| 1.2.2 Casual labour | 2.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 2.4 | 1.5 | 1.2 | 0.0 | 1.6 | 3.1 | 1.8 | 0.0 | 1.7 |

| 1.2.3 Regular wage/salaried | 7.8 | 18.3 | 8.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 9.1 | 18.8 | 41.1 | 19.8 | 9.6 | 0.0 | 23.2 |

| 2. Unemployed | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| 3. In labour force (1+2) | 50.4 | 97.2 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 77.9 | 82.6 | 50.0 | 96.8 | 100.0 | 98.2 | 64.0 | 88.9 |

| 4. Not in labour force | 49.6 | 2.8 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 22.1 | 17.4 | 50.0 | 3.2 | 0.0 | 1.8 | 36.0 | 11.1 |

| 4.1 Students | 44.0 | 0.9 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 15.0 | 38.8 | 0.8 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 7.7 |

| 4.2 Attending domestic duty | 0.7 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.9 | 0.0 | 0.2 |

| 4.3 Too old to work | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 16.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 34.9 | 0.0 |

| 4.4 Other | 5.0 | 1.8 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 5.9 | 2.1 | 11.3 | 2.4 | 0.0 | 0.9 | 1.2 | 3.1 |

| All persons (in per cent) | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| All persons (in number) | 141 | 109 | 86 | 83 | 68 | 419 | 80 | 124 | 96 | 114 | 86 | 414 |

Source: Survey conducted by FAS in 2009 and author’s survey in 2019.

Appendix Table 2 Distribution of activity status of female population by different age-groups, Alabujanahalli in per cent

| 2008–09 | 2018–19 | |||||||||||

| 15–24 | 25–34 | 35–44 | 45–59 | 60+ | 15–59 | 15–24 | 25–34 | 35–44 | 45–59 | 60+ | 15–59 | |

| 1. Workers | 15.0 | 33.7 | 51.9 | 39.6 | 23.1 | 32.2 | 17.3 | 31.3 | 33.7 | 41.2 | 23.8 | 30.6 |

| 1.1 Agriculture | 8.6 | 25.5 | 45.7 | 35.2 | 20.5 | 25.9 | 1.9 | 11.6 | 27.4 | 35.1 | 23.8 | 18.4 |

| 1.1.1 Self-employed | 3.6 | 13.3 | 24.7 | 19.8 | 9.0 | 13.7 | 1.9 | 6.3 | 16.8 | 18.6 | 13.1 | 10.5 |

| 1.1.2 Casual labour | 5.0 | 12.2 | 21.0 | 15.4 | 11.5 | 12.2 | 0.0 | 5.4 | 10.5 | 16.5 | 10.7 | 7.8 |

| 1.2 Non-agriculture | 6.4 | 8.2 | 6.2 | 4.4 | 2.6 | 6.3 | 15.4 | 19.6 | 6.3 | 6.2 | 0.0 | 12.3 |

| 1.2.1 Self-employed | 2.9 | 3.1 | 2.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 2.2 | 0.0 | 1.8 | 3.2 | 3.1 | 0.0 | 2.0 |

| 1.2.2 Casual labour | 0.0 | 1.0 | 0.0 | 2.2 | 1.3 | 0.7 | 1.0 | 1.8 | 0.0 | 1.0 | 0.0 | 1.0 |

| 1.2.3 Regular wage/salaried | 3.6 | 4.1 | 3.7 | 2.2 | 1.3 | 3.4 | 14.4 | 16.1 | 3.2 | 2.1 | 0.0 | 9.3 |

| 2. Unemployed | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.9 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.2 |

| 3. In labour force (1+2) | 15.0 | 33.7 | 51.9 | 39.6 | 23.1 | 32.2 | 17.3 | 32.1 | 33.7 | 41.2 | 23.8 | 30.9 |

| 4. Not in labour force | 85.0 | 66.3 | 48.1 | 60.4 | 76.9 | 67.8 | 82.7 | 67.9 | 66.3 | 58.8 | 76.2 | 69.1 |

| 4.1 Students | 35.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 12.0 | 46.2 | 0.9 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 12.0 |

| 4.2 Attending domestic work | 47.9 | 66.3 | 48.1 | 58.2 | 42.3 | 54.6 | 29.8 | 67.0 | 65.3 | 56.7 | 20.2 | 54.7 |

| 4.3 Too old to work | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 26.9 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.0 | 56.0 | 0.2 |

| 4.4 Other | 2.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 2.2 | 7.7 | 1.2 | 6.7 | 0.0 | 1.1 | 1.0 | 0.0 | 2.2 |

| All persons (in per cent) | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| All persons (in number) | 140 | 98 | 81 | 91 | 78 | 410 | 104 | 112 | 95 | 97 | 84 | 408 |

Source: Survey conducted by FAS in 2009 and author’s survey in 2019.

Appendix Table 3 Distribution of male workforce by age and education levels, Alabujanahalli, in per cent

| 2008–09 | 2018–19 | |||||||||

| 15–24 | 25–34 | 35–44 | 45–59 | 60+ | 15–24 | 25–34 | 35–44 | 45–59 | 60+ | |

| Not literate | 12.7 | 16.0 | 34.9 | 67.5 | 75.5 | 7.5 | 5.8 | 15.6 | 36.6 | 72.7 |

| Literate and up to primary school | 0.0 | 1.9 | 2.3 | 4.8 | 13.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.0 | 0.9 | 5.5 |

| Middle school | 9.9 | 17.0 | 12.8 | 13.3 | 3.8 | 17.5 | 7.5 | 11.5 | 9.8 | 3.6 |

| Secondary school | 39.4 | 34.0 | 15.1 | 6.0 | 7.5 | 27.5 | 25.8 | 39.6 | 19.6 | 7.3 |

| Higher secondary | 21.1 | 11.3 | 17.4 | 3.6 | 0.0 | 22.5 | 15.0 | 13.5 | 18.8 | 5.5 |

| Diploma/ITI | 5.6 | 3.8 | 1.2 | 1.2 | 0.0 | 12.5 | 13.3 | 2.1 | 0.9 | 0.0 |

| Graduation | 8.5 | 13.2 | 16.3 | 3.6 | 0.0 | 12.5 | 24.2 | 14.6 | 12.5 | 5.5 |

| PG and above | 2.8 | 2.8 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 8.3 | 2.1 | 0.9 | 0.0 |

| All workers (in per cent) | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| All workers (in numbers) | 71 | 106 | 86 | 83 | 53 | 40 | 120 | 96 | 112 | 55 |

Appendix Table 4 Distribution of female workforce by age and education levels, Alabujanahalli in per cent

| 2008–09 | 2018–19 | |||||||||

| 15–24 | 25–34 | 35–44 | 45–59 | 60+ | 15–24 | 25–34 | 35–44 | 45–59 | 60+ | |

| Not literate | 33.3 | 57.6 | 85.7 | 88.9 | 100.0 | 0.0 | 20.0 | 43.8 | 80.0 | 95.0 |

| Literate and up to primary school | 0.0 | 3.0 | 2.4 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 2.9 | 9.4 | 2.5 | 0.0 |

| Middle school | 14.3 | 15.2 | 7.1 | 8.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 8.6 | 6.3 | 5.0 | 0.0 |

| Secondary school | 38.1 | 12.1 | 4.8 | 2.8 | 0.0 | 11.1 | 8.6 | 25.0 | 12.5 | 5.0 |

| Higher secondary | 14.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 27.8 | 14.3 | 6.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Diploma/ITI | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 22.2 | 2.9 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Graduation | 0.0 | 9.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 33.3 | 28.6 | 6.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| PG and above | 0.0 | 3.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 5.6 | 14.3 | 3.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| All workers (in per cent) | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| All workers (in numbers) | 21 | 33 | 42 | 36 | 18 | 18 | 35 | 32 | 40 | 20 |

Source: Survey conducted by FAS and author’s survey in 2019.

Date of submission of manuscript: 20th Jan 2023

Date of acceptance for publication: 7th August 2023