ARCHIVE

Vol. 13, No. 1

JANUARY-JUNE, 2023

Editorial

Research Articles

Research Notes and Statistics

Interviews

Book Reviews

Referees

Four Decades of Doi Moi in Viet Nam Agriculture

*Chair, Board of Trustees, International Rice Research Institute, and former Minister of Agriculture and Rural Development of Viet Nam, caoducphat8@gmail.com.

https://doi.org/10.25003/RAS.13.01.0002

Keywords: Viet Nam, Agriculture, Policy Reform, Doi Moi, Rice, Land Policy

Introduction

At the Communist Party Congress of 1986, a decision was taken to initiate Doi Moi, a new set of policy reforms in agriculture. This article describes the key features of Doi Moi, its successes as well as challenges that remain to be addressed.1

Viet Nam has a population of nearly 100 million, of whom 62.7 per cent comprise the rural population. In 2022, 30 per cent of the total labour force worked in agriculture. Agriculture contributed 14 per cent of the overall gross domestic product (GDP) in 2022, down from 38 per cent in 1986.

Viet Nam is a tropical country with a warm climate favourable for agriculture. The deltas of the Mekong River and Red River are very fertile, and among the best places in the world to grow rice. Rice is the main staple for the Vietnamese people. Besides rice, farmers also grow corn, beans, vegetables, and flowers. Coffee, rubber, tea, and cashew are grown in the upland areas of the central and northern mountainous regions. Farmers raise pigs, chickens, ducks, buffaloes, and cows, and a lot of shrimp is cultivated in coastal areas.

Land availability in Viet Nam is limited. The total land acreage is 33.2 million hectares (ha), of which 11.7 million ha is agricultural land and 15.4 million ha is forest land. There are only 1170 square metres or 0.117 ha of agricultural land per capita. Moreover, land available per capita is declining because of urbanisation and industrialisation.

Before the Reform

New Viet Nam was established in 1945, but it was only in 1975 that Viet Nam became fully independent and unified. Viet Nam went through many wars for freedom and independence. These were fought for over a century, and the last one, which ended in 1975, caused huge suffering and losses to humans and the economy. From 1975 onwards, Viet Nam carried out post-war reconstruction of the economy based on a centrally planned economic development approach.

Prior to 1945, agricultural land was mostly owned as private property, and the distribution of land was highly unequal. Farmers constituted 95 per cent of the total population in Viet Nam, but owned less than 30 per cent of arable land. Those with little land or no land constituted 60 per cent of the total population, and owned 10 per cent of land. Feudatory, colonial, and religious landlords, and local managers constituted five per cent of the population, and owned 70 per cent of land (Huyên 1985).

The first major change after the revolution was the land reform. In the North, between 1945 and 1956, 810,000 ha of agricultural land were redistributed to 2.1 million small holders for private use. Land for redistribution came partly from barren land, from land confiscated from colonialists and collaborators with foreign occupants, and partly from land purchased by government from those who owned large estates.2

In the South during the war there were many changes with regard to land introduced by the revolutionary administration and the Saigon regimes. The overall tendency was towards reducing land inequality. After the war ended (from 1975 to 1986), land redistribution was implemented, and 810,710 ha of agricultural land were redistributed to 911,834 landless and small holder households (Phạm 2020). In both North and South (though later), the result was that the distribution of land became more equal.

The second major change in agriculture was that all land in Viet Nam was declared national property in 1980. At the same time, in agriculture there was a movement for creation of cooperatives at different levels. There were more cooperatives in the North, and production groups (a looser form of cooperative) in the South. Farmers contributed land and facilities, equipment, and working animals to form cooperatives. Cooperatives set production plans and organised their implementation. Farmers worked under the guidance of cooperative leaders. At the end of a year, the cooperative allocated revenue to its members in proportion to their contributions in terms of working time and finance, after retaining a portion for maintaining cooperative funds. Farmers received their share both in kind and money. The state provided inputs and bought produce at fixed prices.

State agricultural farms were also set up on former colonial plantations and on large tracts of barren land. By 1985, cooperatives and state farms were the main forms of organisation in agriculture. At the peak of this stage, in 1986, there were 17,022 agricultural cooperatives and 870 state farms (Nhan 2015). Most agricultural land belonged to cooperatives and state farms. State agricultural and forestry farms alone occupied 23 per cent of the total land acreage (Communist Party of Viet Nam (CPV) 2015).

The new land policy made all farmers equal in relation to land. They became co-owners of national land. At the same time, production was organised in cooperatives and state farms. Cooperatives took care of planning, supplying inputs, selling the produce, giving technical guidance, and organising the work of farmers. Farmers thus worked under guidance of the leadership of cooperatives and state farms. In this situation, the state could easily provide assistance to agriculture through cooperatives and state farms as well as buy necessary produce. The system of cooperatives and state farms was key to economic development in the countryside, especially in remote regions. They helped to develop rural infrastructure and facilitated social stability in the countryside. State-owned coffee, rubber, tea, and forestry farms were at the core of development of those subsectors.

A weakness of this system was that it did not provide strong enough incentives for private initiatives, especially to farmers to use resources efficiently. Farmers did not invest their own resources in cooperatives or state farms, except for the small shares they contributed at the time of creating a cooperative. Private investment in agriculture was very low, and productivity was low as well. Agricultural development depended heavily on government investment, which was extremely tight on account of the international situation. Agricultural growth was sluggish, and growth was negative in some subsectors. In 1980, the country faced a food shortage and had to import 1.33 million tonnes of food. Most farmers remained poor. Forests were being cut at an alarming rate and the international situation was unfavourable. All these factors together forced Viet Nam to change policies and introduce Doi Moi or market-oriented economic reforms.

Core Components of Doi Moi in Agriculture

The core components of Doi Moi, the reform in agriculture, were: changes in land policy; introduction of the market mechanism; restructuring cooperatives and state farms; and restructuring public services. All the components were not carried out at one go, but step by step. All the policy changes were interrelated, and every step was made after a careful analysis, review of pilot experiments, and intensive policy debate. The reform process was slow as it took time to understand market mechanisms and establish market institutions. The most important factor was the strong commitment of the ruling party to reform.

Changes in Land Policy

At the beginning of Doi Moi, farmers got contracts from cooperatives or state farms. A contract with a cooperative for rice farmers could be as follows: farmers were responsible for planting, for taking care of the rice field, and for harvesting. Cooperatives were responsible for land preparation, for water management, for supply of fertilizers, and other major inputs. Rice yield from the contracted plot was estimated. After the harvest, farmers had to pay a certain percentage of the estimated yield to the cooperative for services and could retain the rest for themselves. This system strongly encouraged farmers to invest additionally to get a yield higher than the estimated yield. However, such investments were mostly short-term, and farmers were not interested in making longer-term investments on land which did not belong to them.

In 1993, the policy changed to allow land held by cooperatives to be redistributed to farmers for free and for long-term use. In each cooperative, land was distributed equally to all residents locally at the end of that year (Thư Viện Pháp Luật 1993). Initially, the term of land use was 20 years for annual crops and 50 years for perennial-crop plantations. Today, the term of lease is 50 years with automatic renewal. There is, however, a ceiling on land: two to three ha for annual crops, 10 ha for perennial crops, and not more than 30 ha for hilly and mountainous areas.

Land remains national property, but farmers have the right to use, exchange, or transfer this right to others, inherit, grant, use the right as collateral for borrowing, and contribute it as share to form businesses.3 Farmers embraced the new land policy. In 1994, in line with the new policy, 4.95 million ha of agricultural land and 8.41 million ha of forest land were in use by farm households (Cuc and Tiem 1996).

The policy of distributing cooperative land gave farmers direct access to the land but also led to the fragmentation of holdings (Table 1).

Table 1 Distribution of households by size of holding 2006 and 2020, in per cent

| Size of Holding | Percentage of Households | |

| 2006 | 2020 | |

| Less than 0.2 ha | 32.2 | 42.7 |

| 0.2-0.5 ha | 36.5 | 28.1 |

| 0.5-2 ha | 25.4 | 23.3 |

| More than 2 ha | 5.9 | 5.9 |

The data in Table 1 show that even after 15 years of the new policy, the proportion of households with more than two ha was unchanged, while the percentage of those with less than 0.2 ha increased by 33 per cent. Consolidation of land into larger scale commercial agricultural production units has thus not happened.

In state farms, the contract system is still in use. Land for industrialisation and urbanisation has been provided partly by government resuming the land-use rights of farmers with reimbursements based on an “identified” market price. Since the reforms began, the Land Law has been changed every 10 years making farmers’ rights over the land larger, clearer, and more stable. Currently, a new land law is under preparation, it will retain the characteristic of land as national property while allowing land relations to be more market-oriented.

Introduction of the Market Mechanism

There has been a continuous process of market liberalisation and integration as part of Doi Moi. Today, almost all prices of agricultural inputs and outputs are market-based. There are no state-fixed prices for agricultural inputs (except for electricity and petrol) or for produce sold in the domestic market. Almost all direct subsidies to farmers have been removed. Initially, water supply to farmers was free of charge. The new Water Law 2017 introduced irrigation fees.4

More importantly, Viet Nam has opened up the domestic market for international businesses. Viet Nam has become a member of the World Trade Organization (WTO), Association of South East Asian Nations Free Trade Agreement (ASEAN FTA), Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP), European Union-Viet Nam Free Trade Agreement (EVFTA), Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), and other multinational as well as bilateral free trade agreements. These free trade agreements cover almost all agricultural products of Viet Nam.

Market institutions, including laws, have been established by the government, and are continuously monitored and altered when necessary. Domestic agricultural policy has been adjusted to meet requirements of fulfilling international commitments. The government does not allow monopolies or private trusts to engage in agriculture.

Trade liberalisation of agricultural markets, in coordination with other sectors of the economy, and integration gave powerful incentives to farmers to invest in agriculture. Most farmers are commercialised in that they engage with the market economy. To assist farmers, the government has been reducing tax obligations for farmers and agricultural businesses. Since 2003, small farmers have been exempted from the agricultural land use tax.

Restructuring Cooperatives and State Farms

After Doi Moi, cooperatives changed their functions. Members received land plots and cultivated crops on their own. The cooperatives concentrated on activities that individual members could not do as effectively, such as water management and disease control. Farmers were permitted to sell their produce to any trader and keep the full benefit. Farmers paid cooperatives only the cost of services provided. Most cooperatives remained functional, but some ineffective cooperatives were dissolved.

Currently, Viet Nam is giving high priority to the development of new style cooperatives that can help individual farmers be more productive and gain from the market economy. There is, however, no intention to collectivise farms in the old way. Larger scale production is to be promoted by encouraging land consolidation (such as by facilitation of land lease, and exchange and transferring of land use rights).

State farms were restructured too. After a process of review, state farms returned land that they could not use effectively to the state. In the case of plantations of coffee, tea, and rubber, the land of the state farm was given on contract to workers to operate. Similarly, livestock state farms signed contracts with workers to take care of the animals. Many farms even contracted out the land. Farm workers received plots and cultivated them following guidance from the leadership and paid a share of harvest to the state farm.

At the same time, many private companies began to invest in agriculture, including some large businesses, such as TH True Milk and Hoang Anh Gia Lai Group. In 2020, there were 9.1 million farming households, 7918 active cooperatives, and 7471 agricultural companies engaged in agriculture.

Restructuring Public Services

An important constituent of Doi Moi was the restructuring and strengthening of public services, including credit, infrastructure, research and extension, and technical services.

Credit

Before Doi Moi, all banks in Viet Nam were public banks, and they provided almost all the credit advanced to cooperatives and state farms. Now, private banks and credit cooperatives have also been allowed to function. In 2022, there were 124 banks, about 1200 funds, and 16 financial companies that provided credit to agricultural and rural sectors (Ha 2022). Among them, the largest bank is the state-owned Bank for Agriculture and Rural Development (or Agribank), a state corporation, and the Viet Nam Bank for Social Policies, set up in 2002 with the specific objective of directed lending to the poor.

The Government has given priority to providing credit to agricultural and rural sectors. The State Bank sets a ceiling rate of interest and allows commercial banks to provide credit without collateral up to Vietnamese Dong (VND) three billion or USD 127,839 to a farm household or a cooperative. During 2016-2020, the rate of annual increase of credit to agricultural and rural sectors was higher than the average rate of credit provision to the whole economy.

In April 2022, total outstanding amount of credit to the agricultural and rural sectors was VND 2.8 million billion or USD 119 billion, which accounted for 25 per cent of total credit outstanding in the economy. There were 14 million agricultural borrowers. Public sector banks provided about 40 per cent of total rural credit.

The government also created several subsidised credit schemes for the poor and for specific purposes, like the promotion of the application of modern machineries in agriculture. In April 2022, the Bank for Social Policies reported outstanding credit amount of VND 262,917 billion or USD 11 billion to 6.4 million borrowers (The State Bank of Viet Nam 2023).

Infrastructure

The government, with support from international donors, has mobilised resources to invest in upgrading and developing rural infrastructure, including roads, irrigation, and electricity supply networks. In the period 2008-2020, there was a commitment to double public investment for agriculture and rural development every five years (CPV 2008). In 2021, total social investment in agriculture, including both public and private components, constituted about 4.5 per cent of total investment in the country. During the last decade, the quantity of investment in agriculture in real terms has been sluggish and the share of agriculture has also declined. In light of this, recently, a commitment to double public investment for agricultural and rural sectors in the period 2021-2030 compared to 2011-2020 was announced (CPV 2022).

A large share of public investment was allocated to the development of irrigation. Between 2000-2020, nearly two-thirds of the budget allocated through the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development was used for the development of irrigation. As a result, 95 per cent of the rice crop was irrigated.

In 2010, the National Programme of Rural Development was initiated, and this has had a strong impact on rural livelihoods. By 2020, over 99 per cent of communes had main roads asphalted or covered with concrete; 96 per cent of villages had automobile connections; and 100 per cent of communes and 99.5 per cent of rural households were connected to the public electric supply network.

Development of rural infrastructure has linked farmers in remote regions to markets and led to change from self-sufficient agriculture to commodity-oriented agriculture. It is of note that farmers contributed about two-thirds of the resources for the rural development programme (both in kind and cash).

Research and Extension and Technical Services

The government has invested in a big way in the development of public research and extension networks, while encouraging research by private businesses too. However, public investment for research and extension is still low as compared to some other countries. The International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI) estimated that in 2017 Viet Nam invested 0.2 per cent of agriculture GDP for agricultural research while Malaysia invested 0.85 per cent, and Thailand invested 0.94 per cent (Agricultural Science & Technology Indicators 2020).

The government has placed emphasis on promoting research and development of bio-technology in agriculture. Genetically modified (GM) corn has been grown in Viet Nam since 2015, and has produced 1.5 to two times higher yields than non-GM corn. Prior to growing GM corn, on account of the low yield (4-4.5 tonnes per ha), Viet Nam was importing corn for feed, mostly from the US, Brazil, and India.

The extension service was set up to focus on serving cooperatives and state farms. It has been transformed to provide assistance to farm households. At the same time, the incentives provided by the market encouraged farmers to use the extension system, to learn and apply new seeds, new techniques, machinery, and inputs. At the initial stage, labour was abundant. As costs of labour rose, mechanisation expanded.

Veterinary and plant protection services were strengthened following international standards. In addition to the public provision of services, private provision was also allowed.

Impact of Reform

Economic and Social Impact

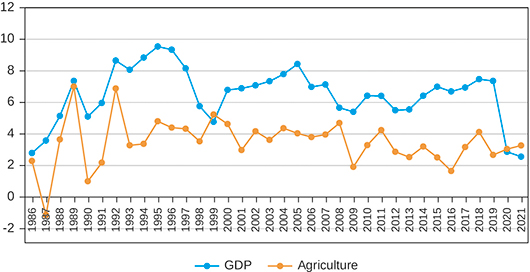

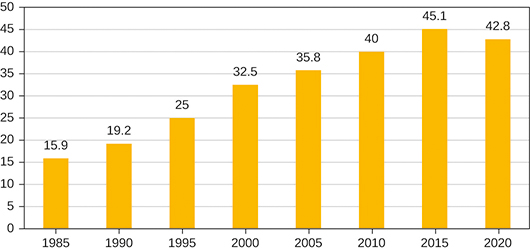

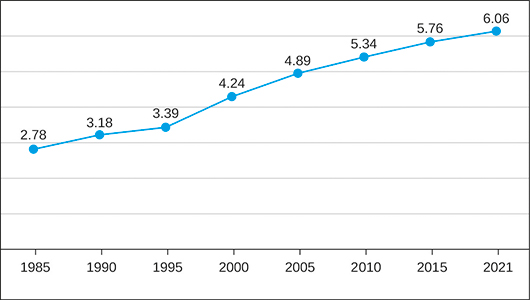

There has been substantial growth in production and yield, even as acreage declined, during the last three and a half decades since the start of Doi Moi. The annual average rate of growth of agricultural output was 3.7 per cent during the period 1988-2021 (Figure 1). In the same period, rice production went up 2.8 times, and rice yields increased 2.2 times (Figures 2 and 3).

Figure 1 Annual rate of growth of GDP and agriculture in per cent

Figure 2 Rice production in million tonnes

Figure 3 Average rice yield in tonnes per ha

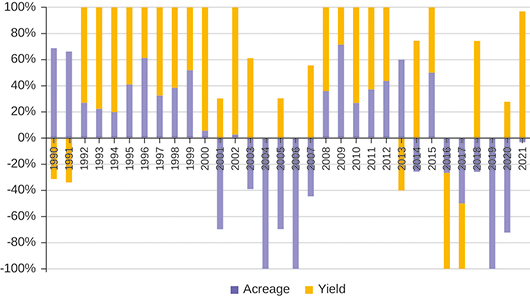

As visible in Figure 4, increase in yields has been the major contributor to change in rice production in recent years.

Figure 4 Contribution of acreage and yield to changes in rice production in per cent

Source: Calculation based on data from General Statistics Office of Viet Nam.

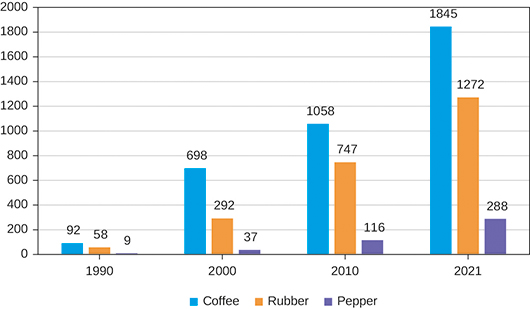

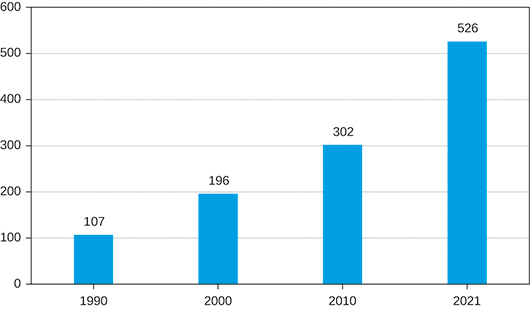

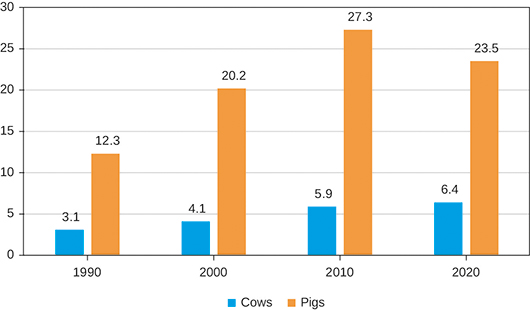

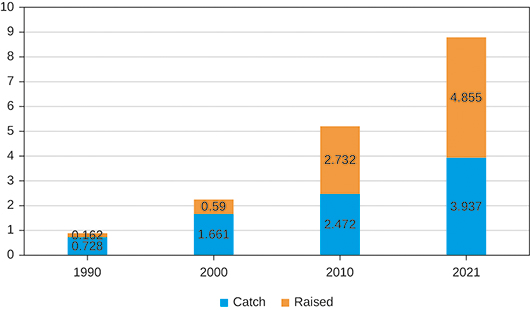

The production of coffee, rubber, pepper, tea, cashew nut, meat, and fishery products jumped as well (Appendix Figures 1-4). Between 1990 and 2021, the production of coffee rose 20 times, rubber 22 times, and pepper 32 times. In the livestock sector, the herd of poultry went up 4.9 times, pigs 2.2 times, and cows 2.1 times. Fishery production grew almost ten-fold. The country has not only ensured food security, but also become a major exporter of many products, including rice, coffee, rubber, cashew nut, pepper, aquaculture, and forestry products. In 2022 alone, Viet Nam exported agricultural, fishery, and forestry products worth USD 53 billion.

There has been rapid and visible improvement in the incomes of farmers. My estimate shows that during the period 1993-2021 Vietnamese farmers’ income rose 16 times. The poverty rate has been declining fast. In 1990, the poverty rate in Viet Nam was 60 per cent (following international standards). In 2021, this rate was 4.4 (following the national multidimensional poverty standards of 2015).

The income poverty lines are now VND two million (USD 85) per person per month for urban areas, and VND 1.5 million (USD 64) per person per month for rural areas. These are more than double the income poverty lines applied for the period 2016-2021 (VND 900,000 and VND 700,000 per person per month). For 2022 and beyond, a new set of multidimensional standards is being applied. Besides income, a household is considered poor if it does not meet three out of six other criteria on employment, health care, education, housing, drinking water availability, and information.5

As about 90 per cent of the poor lived in the countryside, agricultural development has been a major contributor to poverty alleviation in Viet Nam. Agriculture has contributed to most of the rise in income that has shifted poor farm households above the poverty income line. Agricultural development accompanied by rural development has helped reduce the gap between urban and rural areas, preventing excessive migration from rural areas to urban areas. The availability of food at reasonably low prices has helped improve nutrition. Life expectancy has risen steadily, from 64.8 in 1990 to 73.6 in 2021.

Environmental Impact

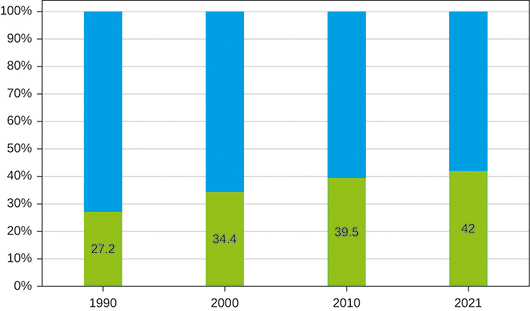

For multiple reasons, Viet Nam experienced deforestation and land degradation for many years, with forest cover going down to 27.2 per cent in 1990. On account of the change in government policy, deforestation was stemmed, and millions of hectares of forest were planted. Now, forests account for 42 per cent of land use (Figure 5).

Figure 5 Forest coverage in per cent

It is important to note that achieving food security and improving livelihoods of farmers were major contributors to achievements in forest protection and development in Viet Nam. Overall, agricultural development is recognised as a foundation for economic development and social stability in the country, especially during periods of crisis such as during the recent Covid-19 pandemic.

Main Challenges

Despite many achievements, agriculture in Viet Nam faces many challenges. Net returns from agriculture remain low. On average, revenue from a hectare of crop land in 2021 was USD 4330.6 Net income was normally about 30-50 per cent of revenues, depending on the costs of production. Revenue also fluctuates as prices of many commodities, such as coffee and rubber are highly volatile. The marginal costs of production have risen, as labour costs have risen. Productivity is high for many crops and seems to have hit a ceiling. And, there is, of course almost no scope for further expansion of arable land.

To increase the incomes of farmers, there is need to further improve productivity while controlling costs of production (or ensuring efficient use of inputs). Income enhancement can also come from diversification of agriculture, and the development of value chains.

The aggregate income of farming households also remained low. In 2021, the average monthly income of rural households was USD 148 per capita. About one-half of this income came from agriculture, and low returns in agriculture and slowing of agricultural growth thus affected overall incomes. The gap between rural and urban incomes continues to widen. Many farmers have shifted to non-farm activities, and some are migrating to urban areas in search of higher incomes. Following the new poverty line (2021), poverty occurrence is still high in remote mountainous areas.

Lastly, there remain challenges in terms of environmental degradation. The chemicals used in modern agriculture have affected the soil and water. Excessive exploitation of aquatic and forest resources has negatively affected biodiversity. Agriculture, rice production in particular, is among the main emitters of greenhouse gases (GHGs), contributing about 20 per cent of total GHGs emissions in Viet Nam.

At the same time, it is forecasted that Viet Nam will be among countries worst affected in the world by climate change, on account of a rise in sea level. A large part of the Mekong delta is likely to be affected by water salinity. Other regions of the country may be affected by severe droughts, floods, or typhoons, which are likely to take place more often and with higher severity. The World Bank forecasts that, by 2050, climate change may cost Viet Nam 12-14.5 per cent of its GDP every year.7 Agriculture as a sector, and households engaged in farming, are the most vulnerable to climate change, and will need to adapt to this change.

Conclusions and Way Forward

In the next 20 to 30 years, Viet Nam aims to join the group of developed countries by further industrialisation and modernisation. In the process, the share of agriculture in gross domestic product (GDP) may fall below 10 per cent, but agriculture will remain an important economic sector. In absolute terms, revenue from agriculture will have to keep growing, as agriculture will remain an important source of employment and income for a large part of the population. Agriculture will also continue to provide a strong environmental base for sustainable development of the country.

To achieve these goals, policy reform will continue to provide incentives with the objective of ensuring fast and sustainable growth of agriculture. These incentives may come from better functioning markets, from the application of science, technology, and innovations; from infrastructure development; human development; and better governance.

Specific areas of reform include the following:

- creating land policy that has clear and stable terms of land use;

- improving the functioning of rural financial markets to meet higher capital needs of farmers;

- fine-tuning commodity market management to improve the competitiveness of national agricultural products;

- creating a favourable environment for businesses to enter and operate in agriculture (in a way that they engage with small holder farmers);

- creating more favourable conditions for research and application of new technology; and

- strengthening incentives for effective and sustainable use of natural resources, reduction of emission and pollution, environment protection, and the development of an ecology-friendly agriculture.

During the last four decades, Viet Nam has carried out a step-by-step market-oriented reform in agriculture. This policy, termed Doi Moi, created strong incentives for farmers and businesses to use land and other resources productively and to invest in agriculture. The outcome was rapid growth in agriculture, which, in turn provided a strong base for economic growth and social stability, especially in times of crisis such as during the recent pandemic. In the coming decades, agriculture will continue to play important roles in economic growth, social development, and environment protection. The government of Viet Nam is continuously engaged in monitoring the agricultural economy, in modifying market-oriented policies, and providing various forms of state support, such as investment in infrastructure and research and extension, so as to ensure further sustainable development of agriculture of Viet Nam.

Notes

1 This is an extended and revised version of the Annual Oration of the Foundation for Agrarian Studies delivered by Dr. Cao Đức Phát on March 29, 2023.

2 For more details, see Law Net (n.d.).

3 For more details, see VNA (2013).

4 For more details, see VNA (2017).

5 See VNA (2021).

6 See GSO (2006, 2020).

7 See The World Bank Group (2022).

References

| Agricultural Science & Technology Indicators (2020), ASTI Country Brief – Viet Nam 2020, available at https://www.asti.cgiar.org/sites/default/files/pdf/Vietnam-CountryBrief-2020.pdf, viewed on April 28, 2023. | |

| Communist Party of Viet Nam (CPV) (2008), Nghị Quyết số 26-NQ/TW, Hội Nghị Lần Thứ Bẩy Ban Chấp Hành Trung ương Đảng (khóa X) Về Nông Nghiệp, Nông Dân, Nông Thôn [Resolution Number 26 NQ/TW, Resolution Consultation of the Xth Central Committee of the Central Sector About Agriculture, Farmers, and Countryside], Aug 5, available at https://tulieuvankien-dangcongsan-vn.translate.goog/van-kien-tu-lieu-ve-dang/hoi-nghi-bch-trung-uong/khoa-x/nghi-quyet-so-26-nqtw-ngay-0582008-hoi-nghi-lan-thu-bay-ban-chap-hanh-trung-uong-dang-khoa-x-ve-nong-nghiep-nong-dan-nong-613?_x_tr_sl=vi&_x_tr_tl=en&_x_tr_hl=en&_x_tr_pto=sc, viewed on April 25, 2023. | |

| Communist Party of Viet Nam (CPV) (2015), Cầnđẩy Mạnh đổi Mới Nông Lâm Trường Quốc Doanh [Facilitation of State Agriculture and Forestry Farms Renewal], available at https://dangcongsan.vn/khuyen-nong-huong-toi-su-phat-trien-ben-vung/tin-tuc/can-day-manh-doi-moi-nong-lam-truong-quoc-doanh-332578.html, viewed on April 28, 2023. | |

| Communist Party of Viet Nam (CPV) (2022), Nghị Quyếtsố 19-NQ/TW, Hội Nghị Lần Thứ Năm Ban Chấp Hành Trung ương Đảng (khóa XIII) Về Nông Nghiệp, Nông Dân, Nông Thôn đếnNăm 2030, Tầm Nhìn đến Năm 2045 [Resolution Number 19 NQ/TW, Resolution Consultation of the of the XIIIth Central Committee About Agriculture, Farmers, and Countryside by 2030, With a Vision to 2045], Jun 16, available at https://tulieuvankien-dangcongsan-vn.translate.goog/he-thong-van-ban/van-ban-cua-dang/nghi-quyet-so-19-nqtw-ngay-1662022-hoi-nghi-lan-thu-nam-ban-chap-hanh-trung-uong-dang-khoa-xiii-ve-nong-nghiep-nong-dan-nong-8629?_x_tr_sl=vi&_x_tr_tl=en&_x_tr_hl=en&_x_tr_pto=sc, viewed on April 25, 2023. | |

| Cuc, Nguyen Sinh, and Tiem, Nguyen An (1996), Half of a Century of Agriculture and Rural Development in Viet Nam (1945-1995), Nhà Xuất Bản Nông Nghiệp, Hồ Chí Minh City. | |

| General Statistics Office of Viet Nam (GSO) (2006), Results of the 2006 Rural, Agricultural, and Fishery Census, available at https://www.gso.gov.vn/en/data-and-statistics/2019/03/results-of-the-2006-rural-agricultural-and-fishery-census/, viewed on April 25, 2023. | |

| General Statistics Office of Viet Nam (GSO) (2020), Results of Mid-Term Rural and Agricultural 2020 Survey, available at https://www.gso.gov.vn/en/data-and-statistics/2022/03/results-of-mid-term-rural-and-agricultural-2020-survey/, viewed on April 25, 2023. | |

| General Statistics Office of Viet Nam (GSO) (n.d.), Economy, available at https://www.gso.gov.vn/en/homepage/, viewed on May 5, 2023. | |

| Ha, Phạm Minh (2022), “Ưu Tiên và Tháogỡ Khó Khăn Vềvố Cho LĩnhVực Nông Nghiệp, Nông Thôn, Góp Phần Ngăn Chặn ‘Tín Dụng đen’” [Prioritising and Removing Capital Difficulties for the Agricultural and Rural Sectors, Contributing to Preventing “Black Credit”], Tạpchí Ngân Hàng, available at https://tapchinganhang.gov.vn/uu-tien-va-thao-go-kho-khan-ve-von-cho-linh-vuc-nong-nghiep-nong-thon-gop-phan-ngan-chan-tin-dung-de.htm, viewed on April 28, 2023. | |

| Huyên, Lâm Quang (1985), Cách Mạng Ruộng Đấtở Miền Nam Việt Nam [The Land Revolution in South Viet Nam], NXB Khoa Học Xã Hội, Hanoi. | |

| Law Net (n. d.), “Luật Cải Cách Ruộng đất 1953” [Land Reform Law 1953], available at https://lawnet.vn/vb/Luat-Cai-cach-ruong-dat-1953-197-SL-8F87.html, viewed on April 28, 2023. | |

| Nhân, Nguyễn Thiện (2015), “Hợp Tác xã Kiểu Mới – Giải Pháp đột Phá Phát Triển Nông Nghiệp Việt Nam (Kỳ 1)” [New Type Cooperatives – Breakthrough Solutions for Agricultural Development in Viet Nam (Part 1)], Nhân Dân, available at https://nhandan.vn/hop-tac-xa-kieu-moi-giai-phap-dot-pha-phat-trien-nong-nghiep-viet-nam-ky-1-post227432.html, viewed on April 28, 2023. | |

| Phạm, Hoài (2020), “Review of Land Redistribution in the South Since 1975 to the Middle 1980s,” Journal of Research and Development, vol. 159, no. 5. | |

| The State Bank of Viet Nam (2023), Bank Resources Always Prioritise Agriculture and Rural Areas, Mar 6, available at https://sbv.gov.vn/webcenter/portal/en/home/sbv/news/Latestnews/Latestnews_chitiet?leftWidth=20%25&showFooter=false&showHeader=false&dDocName=SBV502851&rightWidth=0%25¢erWidth=80%25&_afrLoop=18399954822989023#%40%3F_afrLoop%3D18399954822989023%26centerWidth%3D80%2525%26dDocName%3DSBV502851%26leftWidth%3D20%2525%26rightWidth%3D0%2525%26showFooter%3Dfalse%26showHeader%3Dfalse%26_adf.ctrl-state%3D1bvtnu815z_9, viewed on April 25, 2023. | |

| Thư Viện Pháp Luật (Law Library of Viet Nam) (1993), Quy định vềviệc Giao đất Nông Nghiệp Cho hộ Gia đình, cá Nhânsử Dụngổnđịnh Lâu Dài Vào Mụcđích Sản Xuất Nông Ng Hiệp [Regulation of Agricultural Land Distribution for Long-term Use by Farm Households, Individuals for Agricultural Purposes], available at https://thuvienphapluat.vn/van-ban/Bat-dong-san/Nghi-dinh-64-CP-ban-Quy-dinh-ve-viec-giao-dat-nong-nghiep-cho-ho-gia-dinh-ca-nhan-su-dung-on-dinh-lau-dai-vao-muc-dich-san-xuat-nong-nghiep-38630.aspx, viewed on April 28, 2023. | |

| Viet Nam News Agency (VNA) (2013), Land Law No. 45/2013/QH13, Dec 9, available at https://english.luatvietnam.vn/the-law-no-45-2013-qh13-dated-november-29-2013-of-the-national-assembly-on-land-83386-doc1.html, viewed on April 25, 2023. | |

| Viet Nam News Agency (VNA) (2017), Irrigation Law No. 08/2017/QH14, Jun 19, available at https://english.luatvietnam.vn/law-no-08-2017-qh14-dated-june-19-2017-of-the-national-assembly-on-irrigation-115517-doc1.html, viewed on April 25, 2023. | |

| Viet Nam News Agency (VNA) (2021), Decree No. 07/2021/ND-CP Regulations on Multidimensional Poverty Standards for 2021-2025, Jan 27, available at https://english.luatvietnam.vn/decree-no-07-2021-nd-cp-dated-january-27-2021-of-the-government-on-multidimensional-poverty-standards-in-the-2021-2025-period-197848-doc1.html, viewed on April 25, 2023. | |

| The World Bank Group (2022), Viet Nam Country Climate and Development Report, CCDR Series, available at http://hdl.handle.net/10986/37618, viewed on April 25, 2023. |

Appendix

Appendix Figure 1 Production of coffee, rubber, and pepper in thousand tonnes

Appendix Figure 2 Poultry herd in millions

Appendix Figure 3 Herds of cows and pigs in millions

Appendix Figure 4 Fishery production in million tonnes

Date of submission of manuscript: March 29, 2023

Date of acceptance for publication: May 11, 2023