ARCHIVE

Vol. 14, No. 1

JANUARY-JUNE, 2024

Editorials

Research Articles

Book Reviews

India’s Agricultural Economy, 2014 to 2024: Policies and Outcomes

*Professor, School of Development Studies, Tata Institute of Social Sciences, Mumbai, rr@tiss.ac.in

https://doi.org/10.25003/RAS.14.01.0004

Abstract: This article is an assessment of the state of India’s agricultural sector between 2014 and 2024. It discusses and analyses growth trends, movements of agricultural prices, the economics of cultivation, employment and wages in rural areas, and selected legal reforms and policies of the Narendra Modi government, which has been in office over this period. The data used in the article are drawn from official statistical surveys and reports of the Government of India. The article draws four broad conclusions. First, the period between 2014 and 2024 was marked by an overall economic slowdown and poor growth of employment, particularly in rural India. Incentives to invest deteriorated. Agricultural prices grew slower than the costs of cultivation, leading to a fall in profitability rates and the real incomes of farmers. Secondly, the Government failed to fulfil a series of promises it had made to the rural electorate during its election campaigns in 2014 and 2019, particularly the promises to double farm incomes and raise minimum support prices. Thirdly, the Government’s efforts to amend or reform laws in the domain of agricultural marketing were met with united resistance by farmers’ organisations. Finally, several ill-thought measures of the Government – especially the restrictions on cattle trade, demonetisation, reform of the GST system, and the inadequate response to the Covid-19 pandemic – led to enormous suffering among farmers and adversely affected the health of the agrarian economy. The results of the elections to Parliament in June 2024 have been described as a reflection of the anger of the rural electorate with the Government’s policies and as the success of united rural mass movements.

Keywords: Indian agriculture, agrarian distress, farmers’ movements, rural unemployment.

The state of Indian agriculture was an important issue in the political campaigns leading to the elections to Parliament in India in April–June 2024. These campaigns were preceded by an unprecedented farmers’ agitation; marked by slogans connected to the agrarian movement; interspersed with hostile boycotts of Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) candidates in villages; and assessed by observers as being emblematic of the continuing relevance of agrarian issues in Indian politics. The outcome of the elections, in which the BJP failed to obtain a simple majority, was further evidence that agrarian issues played a significant role in swinging voter preferences, particularly in the rural areas of northern and western India (see the editorial on elections in the Review of Agrarian Studies, this issue).

The importance of agrarian issues in the 2024 election campaign was not based on immediate or short-term grievances of farmers. The fact is that the relationship between the National Democratic Alliance (NDA) government led by Narendra Modi and the farmers of India between 2014 and 2024 has been consistently contentious. First, the Modi government was seen as being responsible for an overall economic slowdown and for poor growth of employment, particularly in rural India. Secondly, the Modi government failed to fulfil a series of promises it made to the farmers in the wake of its election campaigns in 2014 and 2019. Thirdly, the Modi government’s efforts to amend or reform laws in the agricultural domain were met with united resistance from farmers. Finally, several ill-thought measures of the Modi government led to enormous suffering among farmers and affected the health of the agrarian economy adversely.

This article is an appraisal of the policies of the Modi government in agriculture between 2014 and 2024. In particular, it deals with the general state of Indian agriculture, trends in agricultural prices, the economics of cultivation, the conditions of employment and wages in the rural areas, and selected legal reforms and policies, viewing the achievements of the Government in the context of its claims. Data used in this analysis are drawn from official statistical surveys and reports of the Government of India.

The State of Indian Agriculture

Growth Rates of Gross Value Added (GVA)

In this section, I analyse growth trends in the Indian economy with special reference to agriculture. Any analysis of growth rates between 2014 and 2024 must pay special attention to the slowing down of the economy because of the Covid-19 shock, which was felt directly in 2020–21 and 2021–22 and lingered on in 2022–23 and 2023–24. In order to take the impact of the pandemic into account, this section provides two sets of growth estimates: from 2014–15 to 2019–20 and from 2014–15 to 2022–23.

Table 1 provides the growth rates of GDP at market prices across the three main sectors of the economy. While annual growth rates of GDP in industry and services were lower between 2014–15 and 2019–20 and 2014–15 and 2024–25 as compared to between 2004–05 and 2013–14, there was a marginal rise in agricultural growth rates over the same period. However, it was not the sub-sector of “crops” that contributed to the improvement in agricultural growth rates but the relatively smaller sub-sectors of livestock and fisheries.1 The crop sector, which grew at 3.4 per cent per year between 2004–05 and 2013–14, grew at only 2.4 per cent per year between 2014–15 and 2019–20 and 2.8 per cent per year between 2014–15 and 2022–23.

Table 1 Growth rates of gross value added, India, by sectors and sub-sectors, 2004–05 to 2023–24 in per cent per year

| Sector | 2004–05 to 2013–14 | 2014–15 to 2019–20 | 2014–15 to 2023–24 |

| GVA at basic prices | 6.5 | 6.5 | 5.0 |

| Agriculture, forestry, and fishing | 3.6 | 4.7 | 4.5 |

| Crops including irrigation | 3.3 | 2.4 | 2.8 |

| Crops | 3.4 | 2.4 | 2.8 |

| Irrigation | 1.8 | 2.0 | 2.7 |

| Livestock | 6.3 | 8.4 | 7.5 |

| Forestry and logging | –1.1 | 5.5 | 4.8 |

| Fishing and aquaculture | 5.0 | 10.2 | 8.9 |

| Industry | 6.8 | 5.6 | 4.7 |

| Services | 7.5 | 7.4 | 4.7 |

Note: In sub-sectors under agriculture, forestry, and fishing, data are available only till 2022–23.

Source: National Accounts Statistics, Government of India.

Capital Investment in Agriculture

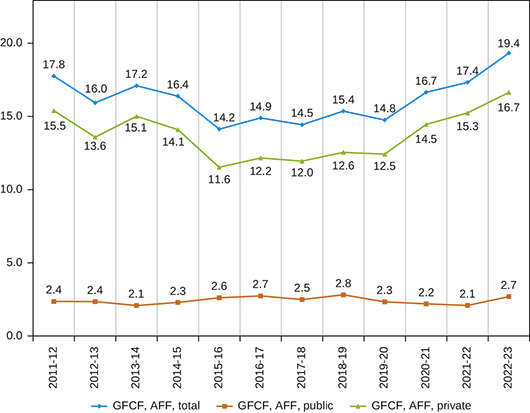

Figures in Table 1 represent only a part of the reality of India’s agricultural macroeconomy after 2014–15. Another important variable of interest is agricultural investment. The most reliable source of information on agricultural investment is the Central Statistics Office’s (CSO) database on gross fixed capital formation (GFCF). Here, we are looking at that part of the nation’s total expenditure on agriculture that is not consumed but added to the nation’s fixed tangible assets. Total GFCF in agriculture was 17.2 per cent of the agricultural GVA in 2013–14, but fell to 14.8 per cent in 2019–20 (see Figure 1). The total GFCF rose as a share of agricultural GVA after 2019–20, but that was solely because of a rise in the share of private GFCF in agricultural GVA and not in the share of public GFCF in agricultural GVA.

Figure 1 GFCF as a share of GVA in agriculture, forestry, and fisheries, India, 2011–12 to 2022–23 in per cent

Source: National Accounts Statistics, Government of India.

The share of private GFCF in agricultural GVA during and after the Covid-19 years rose because there was a rise in the area cultivated and the number of workers employed in agriculture (Ramakumar 2022b). There was a 5 per cent year-on-year rise in the area sown in the kharif season in 2020–21 and a 3.8 per cent rise in the area sown in the rabi season in 2020–21. The area sown in the years that followed remained higher than in 2019–20. The rise in area sown was distress-led, triggered by the widespread loss of livelihoods and employment and consequent return-migration to villages. At the same time, the share of public GFCF in agricultural GVA fell during the pandemic years, a reflection of the conservative fiscal policies of the Union Government.

Prices and Profits in Agriculture

Agricultural Prices

While public investment in agriculture stagnated, – or fell – agricultural prices remained subdued. In this section, I use a simple indicator to assess the movement of agricultural prices. I computed annual growth rates of GVA in agriculture at current and constant prices and computed the difference between the two rates for each year; I call this difference the “sectoral deflator” in agriculture. If the sectoral deflator rose, GVA at current prices was increasingly deviating from GVA at constant prices – an indication that market prices were steadily rising. If the sectoral deflator fell, the GVA at current prices was decreasingly deviating from the GVA at constant prices – an indication that market prices were not steadily rising.

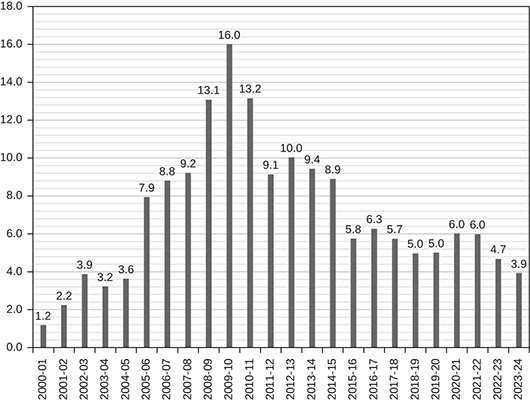

The sectoral deflator in agriculture was rising through the 2000s but fell continuously after 2011–12 (Figure 2). Although there was a tendency for prices to rise during the pandemic, they declined in 2022–23 and 2023–24. Figure 2 clearly shows that the terms of trade were shifting against farmers for most of the 2010s as well as during the post-pandemic years.

Figure 2 Sectoral deflator in agriculture, India, 2001–01 to 2023–24

Source: National Accounts Statistics, Government of India.

Minimum Support Prices

The Union Government could have addressed the problem of stagnation or decline in agricultural prices by raising the minimum support prices (MSPs) of major crops. In fact, a major demand of farmers’ organisations in India – particularly after the report of the National Commission for Farmers (NCF) was published – has been that MSPs for crops must be fixed at a level 50 per cent higher than the C2 cost of production (i.e., the sum of paid out costs, imputed value of family labour, interest on the value of owned capital assets, rent paid for leased-in land, and the rental value of owned land). However, the Modi government refused to accede to the demand and decided to fix MSPs at a level 50 per cent higher than the A2+FL cost of production (i.e., the sum of paid-out costs and imputed value of family labour) only. This meant that the MSPs for crops were fixed at a much lower level than that recommended by the NCF.

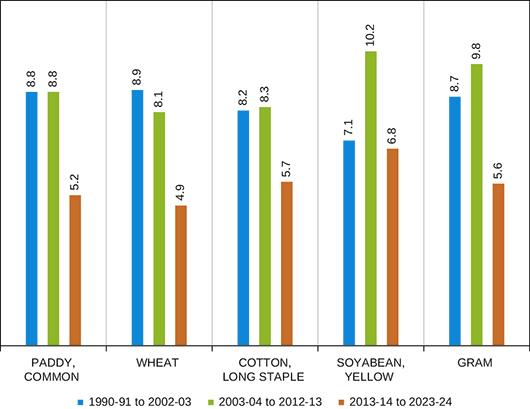

Figure 3 shows the average annual growth rates of MSPs for periods coinciding with the governments led by the United Progressive Alliance (UPA) and the NDA for five selected crops. The MSPs for these crops rose by 8–10 per cent per year between 2003–04 and 2012–13 and rose by only 5 to 6 per cent per year between 2013–14 and 2023–24. In other words, MSPs were growing at a much slower rate during the NDA period than the UPA period.

Figure 3 Average growth rates of MSP for five major crops, India, 1990–91 to 2023–24 in per cent per year

Source: Commission for Agricultural Costs and Prices, Government of India.

The policy on MSPs was a vexed matter during the regime of the NDA and was one of the rallying points for many farmers’ protests against the NDA government. Farmers’ organisations argued that Prime Minister Modi and the BJP reneged on a series of promises made to the electorate. In 2014, speaking at an election rally at Hazaribagh in Jharkhand, Mr Modi had said: “We will change the minimum support price. There will be a new formula—the entire cost of production and 50 per cent profit. It will not only help farmers but … also not allow anyone to loot farmers” (see Varma 2014). Logically, the “entire cost” must be the C2 cost, and not the A2+FL cost. In 2011, as Chief Minister of Gujarat, Narendra Modi chaired a Working Group on Consumer Affairs. The report of the Working Group, submitted to Prime Minister Manmohan Singh, argued that the Union Government must “protect farmer’s interests by mandating through statutory provisions that no farmer-trader transaction should be below MSP” (see Government of India 2011, p. 19).

But once in power, Prime Minister Modi and the NDA government walked away from both these promises. It also provided a curious economic rationale for fixing MSPs at 50 per cent higher than the A2+FL cost – and not the C2 cost. Ramesh Chand, a member of the NITI Aayog, was quoted in The Economic Times on February 3, 2018 as saying:

In my view, the government will take A2 plus FL, to give a margin of 50 per cent for consideration of MSP. The rationale for this is that rental value of own land, which is included in C2, is not incurred by 88 per cent of the farmers.

That 88 per cent of the farmers do not lease in land is no reason to not consider the rental value of owned land as an imputed cost (Ramakumar 2018). An imputed cost is an opportunity cost. An opportunity cost, by definition, is not an actual paid-out cost. For a farmer cultivating their own land, the land could always be rented out. This opportunity cost is in no way dissimilar to the imputation of family labour at the market wage rate. In the latter too, the farmer is not actually earning a wage outside the farm. Yet, it constitutes a wage lost because the farmer forgoes it and chooses to cultivate his or her own farm. That Chand would allow one opportunity cost to stay (the imputed value of family labour) and not another (the rental value of owned land) makes little economic sense.

The Modi government also refused to follow up on the report of the 2011 Working Group on creating a statutory basis for MSPs. This demand was another rallying slogan for farmers’ organisations in their mobilisations prior to the parliamentary elections of 2024. While Mr Modi declared in the Parliament that “MSP was there, MSP is there, MSP will remain,” neither he nor his party provided any justification for not establishing a legal basis for the MSP (Manoj 2021).

Outside the government, neoliberal economists put forward the argument that a higher and statutory MSP would be inflationary. Potential for inflation is not, however, a persuasive argument, because the government can always expand the Public Distribution System – using procured food grains stored in the overflowing godowns of the Food Corporation of India – to bring down market prices. But the NDA government’s food policies were not aimed at expanding food grain procurement. Annual reports of the Commission for Agricultural Costs and Prices (CACP) regularly recommended to the Union Government that open-ended procurement of food grain be ended and that States that paid a bonus on top of the MSPs for food grain be penalised. Though these recommendations were never accepted or implemented, the proposal that a penalty be paid has continued to threaten States that pay farmers a higher price than the official MSP.

Costs and Profitability

While agricultural prices remained subdued and MSPs grew at a slower rate, costs of cultivation were on a continuous rise. A good proportion of the rise in input costs was induced by shifts in public policy that aimed at restricting subsidies for agricultural inputs. Official data show that the rise in the costs of cultivation overtook the rise in MSPs, leading to a fall in profitability rates in a range of crops.

One reason for the rise in input costs was the rise in the prices of fertilizers and other chemical inputs used in cultivation. Indian policy on fertilizers after 1991 – and particularly after 2014 – had three key features. First, there was almost no new capacity generation in the public sector with respect to the domestic production of fertilizers. Consequently, India’s dependence on imported fertilizers rose. Secondly, an increasing role was assigned to the private sector in the import, production, and sale of fertilizers. In 2022, about half of the total production of nitrogenous fertilizers and about three-fourths of the production of phosphoric fertilizers were in the private sector. Thirdly, there was a major shift in the pricing policy that aimed at a full deregulation of the retail prices of phosphoric and potassic fertilizers in the 1990s – and then another shift in 2009 to a nutrient-based subsidy regime that ended up shifting a large part of the production costs to the farmers.

These policy measures had a fundamental impact on the pricing of fertilizers (Ramakumar 2022a; Ramakumar 2022b). They reduced the role of the government in regulating fertilizer prices and increased the retail prices of fertilizers.

Let us consider a recent instance when fertilizer prices rose during the Covid-19 pandemic and the subsequent conflict in Ukraine. In response, the Union Government raised fertilizer subsidies above the budgeted estimate for 2021–22. However, this rise in subsidy allocation was inadequate, as retail fertilizer prices continued to rise. In May 2021, the Union Government asked fertilizer producers not to raise their maximum retail prices (Ramakumar 2022a; Ramakumar 2022b). This request had no impact on retail prices. On the one hand, cooperatives such as the Indian Farmers Fertilizer Cooperative (IFFCO) did partially oblige, by keeping the prices of diammonium phosphate (DAP) unchanged at Rs 1,200 per bag. But they raised the prices of different nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium (NPK) fertilizers. On the other hand, private fertilizer producers did not scale back prices to the levels of 2019. They continued to raise prices. Thus, in the Indian domestic market, the average price of ammonium sulphate rose from Rs 13,037 per tonne in 2017–18 to Rs 20,000 per tonne in 2023–24. The average price of DAP rose from Rs 22,272 per tonne in 2017–18 to Rs 27,000 per tonne in 2023–24. The average price of muriate of potash (MOP) rose from Rs 11,925 per tonne in 2017–18 to Rs 34,040 per tonne in 2023–24.2

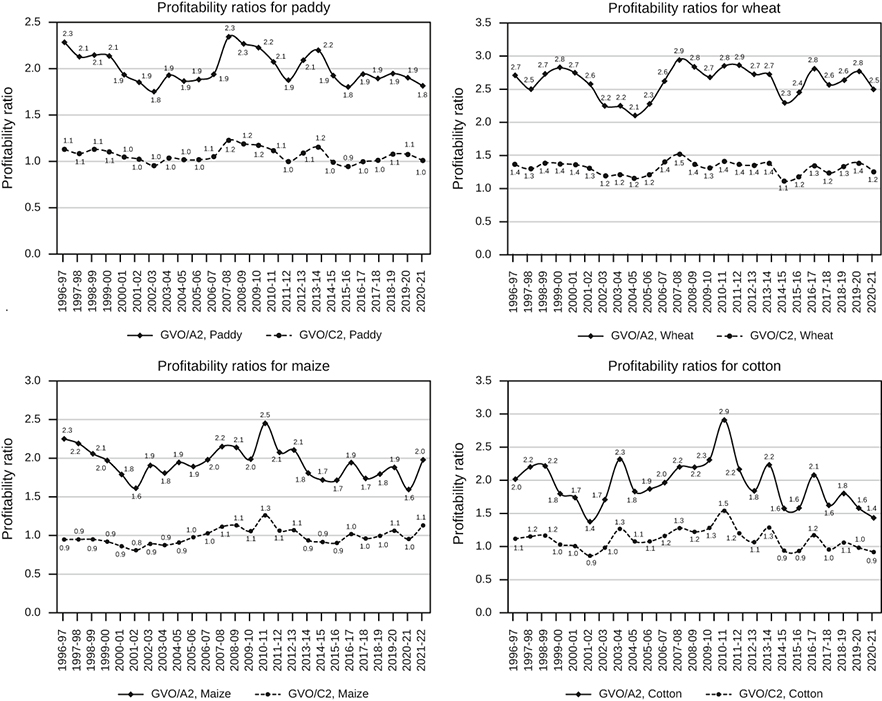

With input prices soaring, and output prices stagnating, profitability rates fell. Figure 4 provides data on the profitability ratios for four crops – paddy, wheat, maize, and cotton – averaged across all States. These ratios are defined in two ways: the ratio of the gross value of output (GVO) and the A2 cost, and the ratio of the GVO and the C2 cost. Both these ratios fell for all four crops after the late-2000s and continued to fall during the period of the Modi government. For all four crops, the fall in GVO to C2 ratio was steeper than GVO to A2 ratio in the 2010s. Further, if we consider the GVO to C2 ratios, the profitability ratio was below one for many years for all the four crops; in other words, cultivation was loss-making if the opportunity costs of land and labour were added to the costs.

Figure 4 Profitability ratios (ratio of GVO to cost A2 and cost C2), paddy, wheat, maize, and cotton, 1996–97 to 2020–21, India

Source: Computed from data in CMIE Economic Outlook.

According to Kamra (2022), who analysed plot-level CCPC data for 13 crops over 17 years between 2000–01 and 2016–17, the crunch in profitability was mainly due to the “double whammy” of a decline or stagnation in output prices and an increase in input prices. The fall of profitability ratios occurred at a time when the costs of living and inflation were rising – and pulled net incomes of farmers down substantially.

Incomes of Farmers

In the Union Budget of 2016–17, the then Finance Minister Arun Jaitley made the major announcement that the Government would “double the income of farmers by 2022.” It became clear later that the objective was to double the real incomes of farmers between 2015 and 2022. A committee was set up to suggest measures to achieve the goal. It submitted 14 reports to the Government. However, none of the major recommendations of the committee were implemented in earnest. An important means available to the government to achieve the goal of doubling farmers’ incomes was the MSP. However, the MSPs grew at a slower rate in the decade of the two NDA governments than in the previous decade. The sharp fall in profitability rates led to an absolute shrinkage of real incomes from cultivation for agricultural households.

Data from the Situation Assessment Surveys (SAS) of 2012–13 and 2018–19 partly attest to this trend (more recent data are not available: Table 2). Over this six-year period, the total monthly income of agricultural households rose by 59 per cent in nominal terms, and by only 26 per cent in real terms. Further, and more importantly, the monthly income from “cultivation” fell in real terms from Rs 2,855 to Rs 2,816 (a –1.4 per cent fall). Total incomes rose because of a rise in incomes from “animal farming” and “wages” – the latter indicating a higher level of proletarianisation among agricultural households in the rural areas. The enormity of the contemporary distress in India’s agrarian society is fully borne out by the absolute fall in real incomes from cultivation.

Table 2 Incomes of agricultural households, India, 2012–13 and 2018–19, by sources, nominal and real incomes in rupees per month

| Source of income | Nominal incomes | Real incomes | ||

| 2012–13 | 2018–19 | 2012–13 | 2018–19 | |

| Cultivation | 3081 | 3798 (23.3) | 2855 | 2816 (–1.4) |

| Animal farming | 763 | 1582 (107.3) | 707 | 1173 (65.9) |

| Wages | 2071 | 4063 (96.2) | 1919 | 3012 (57.0) |

| Non-farm business | 512 | 641 (25.2) | 474 | 475 (0.2) |

| Total | 6426 | 10218 (59.0) | 5954 | 7477 (25.6) |

Note: Figures in parentheses are percentage changes from the previous survey.

Source: Situation Assessment of Agricultural Households, National Sample Survey Office (NSSO), various issues.

Employment and Wages

Employment

Unemployment was an important economic issue in election campaigns in 2024. Most pre- and post-poll surveys of voters recorded that economic and livelihood issues were at the top of the voters’ minds, and unemployment and inflation were among the dominant issues before candidates when they faced their electorates.

The issue of unemployment had become a matter of national discussion as early as 2019. The previous round of the Employment and Unemployment Surveys (EUS) was conducted in 2011–12. The Government decided that the EUS would be discontinued and replaced by an annual Periodic Labour Force Survey (PLFS) from 2017–18. The report of PLFS 2017–18 was not initially released. Media reports indicated that the Government was not releasing the report because the unemployment rate had risen from 2.2 per cent in 2011–12 to 6.1 per cent in 2017–18. The Government first said that the results of the PLFS were not comparable with the results of the EUS. But finally, the Government released the PLFS report of 2017–18 in 2019 with a few cautionary notes in the introduction.

Economists supporting the government argued that while the PLFS rounds of 2017–18 and 2018–19 were of “ uniquely bad quality,” the quality of data improved from 2019–20 onwards (Bhalla 2024). There was no basis for such an assertion as the methodology of organising PLFS rounds remained unchanged from 2017–18 onwards. It would appear that the real reason was that unemployment rates had begun to fall after 2017–18 from 6.1 per cent to 3.2 per cent in 2022–23. Further, the labour force participation rate (LFPR), which had fallen from 39.5 per cent in 2011–12 to 36.9 per cent in 2027–18, had risen to 42.4 per cent by 2022–23. On the eve of the 2024 elections, these numbers were used by economists who worked in the Government to paint a positive narrative (Bhalla and Das 2023). They argued that there was a rapid growth of jobs in India, and that the NDA Government’s policies had overcome the difficulties created by the Covid-19 pandemic.

In rural areas, the overall narrative constructed was similar (see Table 3). There was a rise in the rural unemployment rate, and a fall in the rural LFPR, between 2011–12 and 2017–18, but these trends too were reversed afterwards. If the rural unemployment rate fell from 5.3 per cent in 2017–18 to 2.4 per cent in 2022–23, the rural LFPR had risen from 37 per cent in 2017–18 to 43.4 per cent in 2022–23.

Table 3 Labour force participation rates (LFPR) and unemployment rates, rural India, usual status, principal plus subsidiary, 2004–05 to 2022–23 in per cent

| Year | Rural LFPR | Rural unemployment rates | ||||

| Male | Female | Total | Male | Female | Total | |

| EUS, 2004–05 | 55.5 | 33.3 | 44.6 | 1.6 | 1.8 | 1.7 |

| EUS, 2009–10 | 55.6 | 26.5 | 41.4 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 1.6 |

| EUS, 2011–12 | 55.3 | 25.3 | 40.6 | 1.7 | 1.7 | 1.7 |

| PLFS, 2017–18 | 54.9 | 18.2 | 37.0 | 5.8 | 3.8 | 5.3 |

| PLFS, 2018–19 | 55.1 | 19.7 | 37.7 | 5.6 | 3.5 | 5.0 |

| PLFS, 2019–20 | 56.3 | 24.7 | 40.8 | 4.5 | 2.6 | 4.0 |

| PLFS, 2020–21 | 57.1 | 27.7 | 42.7 | 3.9 | 2.1 | 3.3 |

| PLFS, 2021–22 | 56.9 | 27.2 | 42.2 | 3.8 | 2.1 | 3.3 |

| PLFS, 2022–23 | 55.5 | 30.5 | 43.4 | 2.8 | 1.8 | 2.4 |

Source: NSSO reports, various issues.

A disaggregated analysis, however, shows that the narrative of a fall in rural unemployment and a rise in rural LFPR after 2017–18 was misleading. To begin with, rural unemployment rates in 2022–23 were higher than the levels in 2011–12 and earlier, and rural LFPRs were about the same or a little lower than in the early 2000s. The more pertinent issue is the question of the source of the rise in LFPR in the last five years. I shall try to summarise the argument with reference to four issues.

First, PLFS data after 2017–18 show that while the share of the workforce in India (rural and urban) engaged in casual and regular employment fell, the share of the workforce engaged in self-employment rose (Table 4). The share of self-employed workers in the workforce rose from 52.2 per cent in 2017–18 to 57.3 per cent in 2022–23. Such a rise was predominantly owing to the rise in the share of self-employed female workers in the female workforce from 51.9 per cent in 2017–18 to 65.3 per cent in 2022–23.

Table 4 The share of self-employed workers in the total workforce, India, by region, usual status, principal plus subsidiary, 2017–18 to 2022–23 in per cent

| Year | Share of self-employed workers in the workforce (%) | ||

| Men and women | Men | Women | |

| Rural and urban areas | |||

| 2017–18 | 52.2 | 52.3 | 51.9 |

| 2018–19 | 52.1 | 51.7 | 53.4 |

| 2019–20 | 53.5 | 52.4 | 56.3 |

| 2020–21 | 55.6 | 53.9 | 59.4 |

| 2021–22 | 55.8 | 53.2 | 62.1 |

| 2022–23 | 57.3 | 53.6 | 65.3 |

| Urban areas | |||

| 2017–18 | 38.3 | 39.2 | 34.7 |

| 2018–19 | 37.8 | 38.7 | 34.5 |

| 2019–20 | 37.8 | 38.7 | 34.6 |

| 2020–21 | 39.5 | 39.9 | 38.4 |

| 2021–22 | 39.5 | 39.5 | 39.4 |

| 2022–23 | 39.6 | 39.4 | 40.4 |

| Rural areas | |||

| 2017–18 | 57.8 | 57.8 | 57.7 |

| 2018–19 | 58.0 | 57.4 | 59.6 |

| 2019–20 | 59.8 | 58.4 | 63.0 |

| 2020–21 | 61.3 | 59.7 | 64.8 |

| 2021–22 | 61.5 | 58.6 | 67.8 |

| 2022–23 | 63.0 | 58.8 | 71.0 |

Source: PLFS reports, various issues.

Secondly, if we consider rural and urban areas separately, the rise in the share of self-employed women was less pronounced in urban areas than in rural areas (Table 4). If the share of self-employed women in the female workforce in the urban areas rose from 34.7 per cent in 2017–18 to 40.4 per cent in 2022–23, the corresponding rise in rural areas was from 57.7 per cent in 2017–18 to 71 per cent in 2022–23. In short, the rise in the share of self-employed workers in the national workforce was mainly due to a rise in the share of self-employed female workers in the rural female workforce.

Thirdly, the higher share of self-employed female workers in the rural female workforce was accompanied by a higher share of female workers employed in agriculture. PLFS data show that the share of female workers employed in agriculture (i.e., Divisions 01–03 in the National Industrial Classification 2008) increased from 73.2 per cent in 2017–18 to 75.4 per cent in 2020–21 and 76.2 per cent in 2022–23 (Table 5). At the same time, the share of male workers employed in agriculture fell between 2017–18 and 2022–23.

Table 5 Share of workers employed in agriculture, rural India, usual status, principal plus subsidiary, 2017–18 to 2022–23 in per cent

| Year | Share of rural workers employed in agriculture | ||

| Male | Female | Total | |

| 2017–18 | 55.0 | 73.2 | 59.4 |

| 2018–19 | 53.2 | 71.1 | 57.8 |

| 2019–20 | 55.4 | 75.7 | 61.5 |

| 2020–21 | 53.8 | 75.4 | 60.8 |

| 2021–22 | 51.0 | 75.9 | 59.0 |

| 2022–23 | 49.1 | 76.2 | 58.4 |

Source: PLFS reports, various issues.

Fourthly, if we consider only those workers employed in agriculture, the share of self-employed workers rose from 73.5 per cent in 2017–18 to 80.7 per cent in 2022–23 (Table 6). Here, the increase in share among female workers was more pronounced than among male workers. The share of male workers who were self-employed rose from 77.2 per cent to 82.8 per cent, and the share of female workers who were self-employed rose from 65 per cent to 78.1 per cent. Again, among self-employed women, there was a sharper rise in the share of “own account worker, employer” than in the share of “helper in household enterprise”; in other words, most of the fresh employment was likely unpaid.

Table 6 Percentage distribution of workers within agriculture, by broad status in employment, rural India, usual status, principal plus subsidiary, 2017–18 to 2022–23 in per cent

| Year | Self-employed | Regular wage or salary | Casual labour | Total | ||

| Own account worker | Helper in household enterprise | All self-employed | ||||

| Rural male | ||||||

| 2017–18 | 61.3 | 15.9 | 77.2 | 1.0 | 21.8 | 100.0 |

| 2018–19 | 62.2 | 15.0 | 77.2 | 1.1 | 21.7 | 100.0 |

| 2019–20 | 59.8 | 16.8 | 76.6 | 1.7 | 21.7 | 100.0 |

| 2020–21 | 60.4 | 18.0 | 78.4 | 1.4 | 20.2 | 100.0 |

| 2021–22 | 60.6 | 19.6 | 80.2 | 0.9 | 18.9 | 100.0 |

| 2022–23 | 63.4 | 19.4 | 82.8 | 1.1 | 16.1 | 100.0 |

| Rural female | ||||||

| 2017–18 | 16.3 | 48.7 | 65.0 | 1.2 | 33.8 | 100.0 |

| 2018–19 | 18.4 | 49.4 | 67.8 | 1.1 | 31.1 | 100.0 |

| 2019–20 | 18.0 | 52.7 | 70.7 | 1.7 | 27.6 | 100.0 |

| 2020–21 | 19.9 | 53.3 | 73.2 | 1.1 | 25.7 | 100.0 |

| 2021–22 | 23.3 | 52.5 | 75.8 | 0.6 | 23.6 | 100.0 |

| 2022–23 | 26.4 | 51.7 | 78.1 | 0.5 | 21.4 | 100.0 |

| Rural, male and female | ||||||

| 2017–18 | 47.8 | 25.7 | 73.5 | 1.1 | 25.4 | 100.0 |

| 2018–19 | 48.2 | 26.0 | 74.2 | 1.1 | 24.7 | 100.0 |

| 2019–20 | 44.3 | 30.1 | 74.4 | 1.7 | 23.9 | 100.0 |

| 2020–21 | 44.2 | 32.1 | 76.3 | 1.3 | 22.4 | 100.0 |

| 2021–22 | 45.2 | 33.2 | 78.4 | 0.8 | 20.8 | 100.0 |

| 2022–23 | 46.8 | 33.9 | 80.7 | 0.8 | 18.5 | 100.0 |

Note: The figures in italics are the two component parts of “all self-employed.”

Source: PLFS reports, various issues.

Put together, the four points above indicate that the rise in rural LFPR and fall in rural unemployment were not because of any general expansion of meaningful and paid employment, but because of a rise in largely unpaid forms of self-employment among rural women in agriculture. Such a phenomenon may partly be attributed to conditions of economic distress in the non-agricultural spheres in urban areas and the shutdown of urban enterprises because of three distinct developments: demonetisation in 2016, GST reform in 2017, and the Covid-19 pandemic in 2020 and 2021. Because of a loss of employment in urban areas, particularly because of the Covid-19 pandemic, large sections of the urban workforce migrated back to their villages. In their villages, these men and women may have been involved in agricultural activities on own farms – mostly without payment. Women in rural areas may also have been drawn into agriculture on their own family farms – partly to reduce the wage bills for hired workers and partly to expand area under cultivation or intensify cultivation.

It could also well be the case that the explanation above is incorrect, and that improved measurement of unpaid female work in the PLFS may be showing up as higher female self-employment. If such is the case, the argument of higher employment generation put forward by the government does not hold. Either way, the government’s claims on employment hardly stand up to scrutiny.

A rise in skilled agricultural workers?

As it became amply clear that it was higher female self-employment in agriculture in rural India that led to a lower unemployment rate and a higher LFPR after 2017–18, government economists attempted a new spin in the early months of 2024. The Ministry of Finance released a report in January 2024 in which it was argued that the rise in the share of female workers in agriculture represented a “structural shift” (Government of India 2024). According to the report, there was a rise in the proportion of “skilled agriculture labour” from 48 per cent in 2018–19 to 59.2 per cent in 2022–23 and a concomitant decline in “elementary agriculture labourers” from 23.4 per cent in 2018–19 to 16.6 per cent in 2022–23. It was added that within the “skilled agriculture female workers,” the share of “market-oriented workers” had risen during the same period. In short, the report argued that:

The feminisation of agriculture also points to a much-needed structural shift within agriculture, where excess (male) labour moves out and remaining (female) labour is utilised efficiently. Thus, female participation in rural India is productive and remunerative. The monetary contribution of women to rural family incomes also matters from the lens of intra-household bargaining power and decision-making, propelling a tectonic shift in the societal gender dynamics (Government of India 2024, p. 51).

Such a grand justification for a retrogressive trend in the rural labour market was weak and wrong – both in conception and articulation. Here, the Ministry of Finance was using the classifications used in the PLFS rounds drawn from the three-digit National Classification of Occupations 2015 (NCO-2015).3 The NCO-2015 is based on a classification of workers used by the International Labour Organisation (ILO) called the International Standard Classification of Occupations (ISCO). In ISCO, the concept of “skill” has a specific meaning and is defined as “the ability to carry out the tasks and duties of a given job” (Directorate General of Employment [DGE] 2016, p. 5). But more importantly, the classification of workers based on their skill levels is not based on the skills acquired or required to undertake the tasks defined but based on the educational categories and levels of the workers. All NCO manuals emphasise that “the focus was on the skills required to carry out the tasks and duties of an occupation and not on whether a worker working in a particular occupation is more or less skilled than another worker in the same occupation” (DGE 2016).

In NCO-2015, there are nine Divisions into which workers are classified. Of these, Division 6 refers to “Skilled Agricultural, Forestry and Fishery Workers” and Division 9 refers to “Elementary Occupations.” These were the two Divisions referred to by the Ministry of Finance. The skill level in Division 6 corresponds to “Secondary Education” i.e., “11-13 years of formal education.” The skill level in Division 9 corresponds to “Primary Education” i.e., “up to 10 years of formal education and/or informal skills.” To illustrate, if there are two workers in agriculture, the decision on whether to classify them into Division 6 or Division 9 is not based on the nature of work performed but on whether they have attained secondary education or primary education. The argument in Government of India (2024) was that the rise in the share of workers in Division 6 implied a rise in the share of skilled workers in agriculture – a phenomenon argued to be indicative of a transformation of the labour force in agriculture. Such an argument is wrong because the tasks performed by “Skilled Agricultural, Forestry and Fishery Workers” are defined as follows:

Skilled agricultural, forestry and fishery workers grow and harvest field or tree and shrub crops, gather wild fruits and plants, breed, tend or hunt animals, produce a variety of animal husbandry products, cultivate, conserve and exploit forests, breed or catch fish and cultivate or gather other forms of aquatic life in order to provide food, shelter and income for themselves and their households” (DGE 2016, pp. 945–46).4

As opposed to this, NCO manuals define the tasks performed in “elementary occupations” thus: “Elementary Occupations involve the performance of simple and routine tasks which may require the use of hand-held tools and considerable physical effort.”5

In short, there is nothing special about workers in Division 6 – as compared to workers in Division 9 – that indicates the need for improved “skill” as we know it, i.e., the ability to use one’s acquired knowledge more effectively in the execution or performance of a task at hand.6 By definition, the skill levels attributed to Division 6 are not related to any specific acquisition of knowledge but are based on a simple correspondence with a specified level of educational achievement. Consequently, a rise in the share of workers in Division 6 is just a reaffirmation of the inference – already discussed – of a rise in the share of self-employed workers in agriculture and nothing more.

The other argument in Government of India (2024) on the rise of market orientation within workers in Division 6 is also misleading. Division 6 is sub-divided into three Sub-Divisions: Market Oriented Skilled Agricultural Workers (Sub-Division 61); Market Oriented Skilled Forestry, Fishery and Hunting Workers (Sub-Division 62); and Subsistence Farmers, Fishers, Hunters and Gatherers (Sub-Division 63). The only difference between Sub-Divisions 61 and 62 on the one side, and Sub-Division 63 on the other, is that the former two require that the work undertaken is “for sale or delivery on a regular basis to wholesale buyers, and marketing organizations or at markets” while the latter requires that the work is undertaken “in order to provide food, shelter and a minimum of cash income for themselves and their households” (DGE 2016, pp. 366–1519). Thus, at best, a rise in the share of workers in Sub-Divisions 61 and 62 show a rise in the share of workers employed in farms with a marketable surplus, and nothing more. It is in no way representative of any “structural shift” – leave alone any “tectonic shift” – within the rural workforce, as the report of Government of India (2024) claimed.

Wages

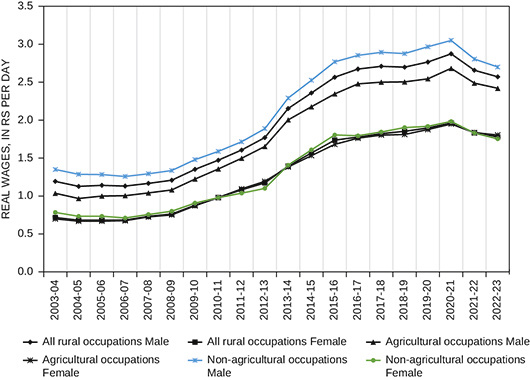

Real wages in agricultural and rural occupations in India rose from the mid-2000s after a period of decline between 1997–98 and 2004–05. The rise of real wages after the mid-2000s has been the subject of many studies. According to Das and Usami (2017), the growth rate of agricultural wages between 2007–08 and 2016–17 was “above 5.5 per cent per annum for most large States, and across all occupations, agricultural and non-agricultural, and for males and females.”

There were different reasons for the rise in wage rates after the mid-2000s. There was a reasonable growth in the non-agricultural sector – particularly the construction sector – that drew workers out of agriculture. The Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme (MGNREGS) provided millions of person-days of work every year in rural areas. Both these phenomena might have led to increased demand in the rural labour market after 2009–10, leading to a rise in wages.

However, as Figure 5 shows, real wages in rural and agricultural operations stagnated after 2016–17, particularly after demonetisation in November 2016 (Ramakumar 2018). Demonetisation and the GST reform that followed were associated with the closure of several non-agricultural enterprises in the informal sector and the capture of their market shares by an expanding formal sector. These developments may have led to a crowding of the rural labour market, particularly in agriculture. Further, MGNREGS did not expand in this period to compensate for any loss of jobs. A report by India Ratings argued that though MGNREGS “may have helped shield nominal wages from falling after 2016–17, the scheme did not provide the necessary impetus to strengthen real wage growth and reduce rural distress in a significant way” (Bharadwaj 2018).

Figure 5 Trends in real wages in agricultural and non-agricultural occupations, rural India, 2003–04 to 2022–23 in rupees per day

Note: Nominal wages were deflated by the wholesale price index to estimate the real wages.

Source: Wage Rates in Rural India, Labour Bureau, various issues.

More importantly, after stagnating between 2016–17 and 2020–21, real wages in all rural occupations fell in 2021–22 and 2022–23 for the first time after many decades (see Das and Usami (2024) for a detailed analysis). Here again, the significant loss of jobs in the formal and informal sectors in the urban areas, the return migration of hundreds of thousands of workers to rural areas, and their entry into the rural labour market may have led to yet another round of crowding of the rural labour market and precipitated the fall in real wages. As we concluded in the previous sub-section, there was a significant rise in the share of self-employed men and women in the agricultural workforce during and after the Covid-19 pandemic.

It is important to highlight the fact that the stagnation and fall of real wages in agriculture and rural occupations was accompanied by an absence of the generation of any new and meaningful employment in the rural areas – a point that we noted in the last sub-section. Also, although nominal wages rose throughout this period, high inflation eroded these, leading even to a fall in real wages.

Ill-planned Policies

In the previous sub-sections, we used official data to discuss the nature of deterioration in the economics of agriculture and the rural economy after 2014–15. However, it is equally important to highlight five distinct policy attempts of the Modi government that, over a decade, cumulatively resulted in a rise in the economic burdens on farmers and a serious loss of the BJP’s political credibility in the rural areas. These attempts also led to the formation of a broad political platform of resistance against the Modi government in the rural areas.

The Land Acquisition Ordinance, 2014

With the advent of neoliberal policies after 1991, India’s Land Acquisition Act, 1894, was criticised severely. There were more and more instances of dispossession, leading to new protests and the demand for democratic and just legislation. At the same time, private capital began to demand more investment-friendly land legislation. Negotiations undertaken by the UPA government to settle the issues outstanding led to the enactment of the Right to Fair Compensation and Transparency in Land Acquisition, Rehabilitation and Resettlement (RFCTLARR) Act of 2013. Despite its limitations, the RFCTLARR Act was more consultative and participatory than its draconian predecessor. It was a rights-based legislation that offered many advantages to land holders vis-à-vis industry.

Within six months of coming to power in 2014, however, the Modi government issued an ordinance that amended the RFCTLARR Act in a way to placate industrial organisations and corporate houses. This ordinance diluted several protective clauses in the RFCTLARR Act and reinstated the “eminent domain” of the state to not just acquire land without consent but also in allowing the forcible acquisition of land for “private purposes.” The ordinance led to nation-wide protests. The All India Kisan Sabha, India’s largest peasant organisation, brought more than 300 State-level groups of farmers’ organisations, agricultural workers, and social movements into a national platform called the Bhoomi Adhikar Andolan (Movement for Land Rights). This platform demanded that the ordinance be withdrawn. Copies of the ordinance were publicly burnt in more than 300 districts in the country. Two marches to Parliament and public hearings in different parts of the country were also organised.

The Bhoomi Adhikar Andolan and its protests were able to achieve an issue-based political unity across peasant and rural organisations and give a degree of public prominence to the issue of land acquisition as a political question. The movement was able to force the government to drop its effort to convert the ordinance into legislation. Though the government was able to pass the RFCTLARR Amendment Bill in the Lok Sabha, it was not able to do so in the Rajya Sabha. This was the first political success of the farmers’ movement after the BJP came to office in May 2014.

Restrictions on Cow Slaughter and Cattle Trade

Opposition to cow slaughter has historically been part of the BJP’s political agenda. Soon after the Modi government came to power in 2014, there were a series of vigilante attacks on Muslims and Dalits engaged in the economic activities of rearing, trade, and transport of cattle. Groups linked to the larger Sangh Parivar, who called themselves gau rakshaks, were behind these attacks. In September 2015, Mohammed Akhlaq was attacked and lynched in Dadri, Uttar Pradesh by a mob that accused him of slaughtering a calf. In March 2016, Mazlum Ansari and Imtiaz Khan (a 12-year-old minor) were lynched and hung from a tree in Latehar, Jharkhand while transporting eight oxen for sale in a cattle market. In August 2016, four Dalit youth were stripped and flogged in Una, Gujarat for refusing to skin dead cattle in their village. In April 2017, a livestock farmer Pehlu Khan was lynched in Alwar, Rajasthan while returning from a cattle market in Jaipur with the cows and calves that he had purchased.

Instead of curbing these attacks and ensuring the rule of law, the Ministry of Environment and Forests issued a notification that restricted cattle trade. The Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (Regulation of Livestock Markets) Rules, 2017 was a politically motivated notification that aimed to curb the rights of farmers engaged in dairy farming, workers employed in the leather industry, and minority groups that engaged in meat trade. These Rules imposed restrictions on the sale of cattle and camels, making it impossible for farmers to sell ageing livestock; consequently, farmers could not mobilise capital to purchase new livestock. Cattle could be purchased only on the guarantee that they would be used in agricultural operations alone, and any purchased cattle could not be resold for six months. Any sale or purchase was to be accompanied by a slew of approvals and no-objection certificates. In short, apart from the horror of vigilante attacks, farmers were left burdened with aged livestock that they could neither sell nor afford to feed.

The 2017 notification was a national-level regulation that grossly disregarded the fact that animal husbandry is in the State List of the Constitution and prevented cow slaughter in various Indian States where it was permitted. It violated the occupational rights of citizens and their freedom to buy and consume food of their choice.

Peasant organisations also came together to resist the 2017 notification. On the ground, the Bhoomi Adhikar Andolan was revived as a platform of unity to resist cattle trade restrictions and demand actions against gau rakshaks (“cow protectors”). The All India Kisan Sabha approached the Supreme Court of India, impleading itself in an ongoing case. Although the notification was stayed by the Supreme Court, the Government of India notified a new draft of the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (Regulation of Livestock Markets) Rules, 2018. The 2018 Rules omitted the 2017 clause that disallowed the purchase and selling of cattle for slaughter. Also omitted was the clause that forced buyers to attest that cattle were not being purchased for slaughter. In 2019, the matter of preventing cruelty to animals was officially transferred from the Ministry of Environment and Forests to the Department of Animal Husbandry and Dairying. These were major retractions on the part of the government and represented another important success for farmers’ organisations.

Demonetisation

The sudden decision to demonetise notes of denomination Rs 500 and Rs 1,000 on November 8, 2016 was a major blow to the agrarian economy. Agriculture has historically been India’s largest informal economy, and economic transactions in rural India are largely cash-based. In 2015–16, the unorganised sector accounted for about 95 per cent of the gross value added in agriculture and about 42 per cent of the gross value added in services (Reserve Bank of India 2017). The unorganised sector also accounted for 82.4 per cent of the total employment in the economy, of which 48.7 per cent was in agriculture, 8.5 per cent was in industry, and 25.2 per cent in services.

The cash crunch caused by demonetisation limited farmers’ capacity to buy seeds and other inputs on time and at reasonable prices. Farmers were forced to borrow from moneylenders at high interest rates to pay for inputs. Demonetisation also had two kinds of impact on agricultural markets. First, in the first few weeks or months, it disrupted agricultural supply chains across the country. Monsoon-crop (kharif) harvests arrived in market regulated by the state (mandi) in November 2016. Cash shortages disrupted the smooth sale of the harvest. In some regions, traders did not buy farmers’ harvests from fields and yards. In other regions, farmers were forced to sell at lower-than-market prices to traders or sell in exchange for older notes of Rs 500 and Rs 1,000. Consequently, there was a sharp decline of arrivals in agricultural markets in November and December 2016 (Ramakumar 2018).

Secondly, demonetisation upset some systemic features of agricultural markets. Traders in mandis managed their liabilities by resorting to different methods of cash flow management. When cash was not immediately available, traders borrowed from informal sources and repaid when cash arrived (Ramakumar 2019b).

All of this came to a standstill after demonetisation, as cash was sucked out of the system. Many small traders were forced out of business. Some traders began to use cheques to delay payments, but few buyers were ready to accept them. As a result, mandi trade was severely undermined. The prices of many commodities fell precipitously. Farmers producing perishable commodities – fruit and vegetables – who did not have access to storage facilities were among the worst affected.

The decline of agricultural prices and farmers’ incomes after demonetisation was a rallying factor in the farmers’ protests that swept the Indian countryside in May and June of 2017. Maharashtra, Madhya Pradesh, Haryana, Rajasthan, and Punjab witnessed intense protests. Faced with a serious reduction of incomes and profitability, farmers blocked highways and cut off food supplies to cities; they demanded a waiver of outstanding farm loans and that MSPs be fixed at 150 per cent of the C2 cost of production. On June 6, 2017, six people died when police fired at a farmers’ protest in Mandsaur, Madhya Pradesh.

The Mandsaur firing led to a new wave of issue-based unity among organisations of farmers and rural workers. In June 2017, more than 200 rural organisations formed a new platform, the All India Kisan Sangharsh Coordination Committee (AIKSCC, or the All-India Farmers Struggle Coordination Committee). Two demands of the AIKSCC were that the repayment of farm loans be waived and that MSPs be fixed according to the recommendations of the National Commission for Farmers. In July 2017, there was a partial success when the Government of Maharashtra announced a loan waiver package worth Rs 34,000 crore.

GST Reform

The Goods and Services Tax (GST) system that was introduced in 2017 imposed some new economic burdens on agriculture. While farmers were exempt from GST, many agricultural inputs and services that were not taxed earlier were newly brought into the tax net.

Prior to the introduction of GST, the tax on fertilizers varied from zero to 8 per cent. In fact, farm implements, fertilizers, and pesticides were exempt from taxes in States like Punjab, Haryana, and Andhra Pradesh (Agro-Economic Research Centre 2019). When GST was introduced in 2017, the tax rate on fertilizers was initially fixed at 12 per cent but was later brought down to 5 per cent. Consequently, in a few States where the combined VAT and excise duties prior to 2017 were about 6 per cent, the retail prices of fertilizers fell marginally. In States like Punjab, Haryana, and Andhra Pradesh, however, where there was no VAT and about 1 per cent excise duty on fertilizers, retail prices rose considerably. Another issue was that while the GST rates on final fertilizers were fixed at 5 per cent, the rates for specific raw materials like sulphuric acid and ammonia were fixed at 18 per cent (ostensibly to avoid end use-exemptions and reduce misuse). As a result, in the case of specific fertilizers for which sulphuric acid and ammonia were raw material, domestic manufacturers were disadvantaged over imports, leading to an upward push to retail prices.

The tax on drip and sprinkler irrigation equipment increased from 5 per cent to 18 per cent. The tax on pesticide sprayers increased from 6 per cent to 18 per cent and on electric motors, from 7 per cent to 12 per cent. The tax on tractors of capacity less than 1,800 cc was brought down from 18.5 per cent to 12 per cent, but on road tractors of capacity more than 1,800 cc, it was raised from 5 per cent to 28 per cent.

The tax on packaged food, preserved vegetables, jams, jellies, and sauces was raised from 5 per cent to 12 per cent. The tax on butter, ghee, cheese, and dried nuts like almonds and hazelnuts was raised from 6 per cent to 12 per cent. In addition, different kinds of packing material used in agriculture, including gunny bags, were brought into the GST net. Activities like animal breeding, dairy farming, poultry farming, chopping wood and grass, fruit farming, growing artificial forests, and raising seedlings and plants were not included under the definition of “agriculture,” and hence also brought into the GST net. Together, these changes led to higher administrative costs for traders, lower margins for dealers, and higher costs of production for farmers.7

The Three Farm Laws

By convention, legislation covering agricultural marketing has been the concern of State Governments. This convention was broken in 2020, when the Union Government took upon itself the task of legislating on agricultural marketing and passed three farm laws in Parliament.

The three farm laws were related to the rules that governed the operation of regulated markets – or mandis – and private markets in rural India, contract farming, and trade in essential commodities. The Government’s argument was that if India wanted to diversify its cropping pattern into export-oriented and high-value crops, mandis had to give way to private markets, futures markets, and contract farming. Thus, the first two laws were efforts to ensure that any private market or rural collection centre could freely be established anywhere without the approval of the local mandi or the payment of a mandi tax. This was intended to accelerate the spread of contract farming. The third law did away with stock-limits for traders under the Essential Commodities Act, 1955. This was intended to incentivise private corporate investment in storage and warehousing.

To begin with, the three farm laws violated States’ rights as established in the Constitution (see Ramakumar (2022a) for details).

Apart from the question of constitutionality, the overall thrust of the farm laws was to encourage the participation of large corporate players in agricultural markets rather than farmer-friendly organisations, such as cooperatives or Farmer Producer Companies (Ramakumar 2022a). Especially in the case of the amendment of the Essential Commodities Act, there was reasonable suspicion that a handful of corporate players would benefit substantially from new investments in logistics, storage, and warehousing. The grievance-redressal mechanisms envisaged in the law on contract farming were also criticised as being biased towards corporate sponsors and against contracting farmers.

A major protest movement of farmers against the three farm laws began in northern India in 2020 and went on for more than a year. A new united platform called the Samyukta Kisan Morcha (SKM, or United Farmers Movement) was established by the groups that were earlier part of AIKSCC. The farmers’ protests began in States like Punjab and Haryana where mandis were deeply rooted institutions in the local economy and society. As days went by, the movement spread to western Uttar Pradesh and then to many other States. In a few months, the protest spread to different parts of India where local demands were added to the larger demand for the repeal of the three farm laws. Large numbers of women participated in the protests. About 702 protestors died on the protest grounds, according to the SKM. Support for the protests grew in India and abroad (IANS 2021).

The Union Government’s response to the protests was brutal. Efforts were made to break, divide, buy out, demean, demonise, and shame the protestors. Protesting farmers were called terrorists and Sikh separatists (Khalistani). Sedition cases were filed against the protestors. Tear gas shells were fired at different places, and, at one site, officials asked the police to “smash the heads of protestors” (Scroll Staff 2021). In Lakhimpur Kheri, Uttar Pradesh, a car rammed into a peaceful demonstration killing four protestors (Rashid and Singh 2021). The protests continued, and endured.

The Government of India retreated and repealed the three laws on November 20, 2021, establishing a historic victory for the farmers’ movement.

Concluding Points

This article makes four broad points. First, the overall state of the agrarian economy between 2014 and 2024 was marked by poor incentives to invest and a slow growth of agricultural prices. Secondly, profitability rates in agriculture declined across crops, leading to a fall in real incomes from cultivation for agricultural households. The government failed to control rising input prices or to compensate farmers by means of higher Minimum Support Prices (MSPs). Thirdly, the government failed to fulfil the promises it made, such as to double farm incomes or to institute laws to make the payment of MSPs mandatory. Finally, the multiple policy interventions of the government in the agrarian economy – such as the effort to dilute land acquisition laws, the effort to restrict cattle trade, demonetisation, GST reform and the enactment of the three farm laws – created great anger among farmers and created the basis for new unity across agrarian and rural organisations. The results of the 2024 elections to the Parliament – which were a clear reflection of the anger of the rural electorate against the policies of the Government of India led by the BJP – were a measure of the success of united rural mass movements.

Notes

1 In 2022–23, the livestock and fisheries sectors together contributed 38 per cent to GVA in agriculture, forestry, and fishing, while the crop sector contributed the largest share, 54 per cent.

3 The other classification used is the five-digit National Industrial Classification released in 2008, or NIC-2008.

4 More specifically, the tasks include “preparing the soil; sowing, planting, spraying, fertilising and harvesting field crops; growing fruit and other tree and shrub crops; growing garden vegetables and horticultural products; gathering wild fruits and plants; breeding, raising, tending or hunting animals mainly to obtain meat, milk, hair, fur, skin, sericulture, apiarian or other products; cultivating, conserving and exploiting forests; breeding or catching fish; cultivating or gathering other forms of aquatic life; storing and carrying out some basic processing of their produce; selling their products to purchasers, marketing organizations or at markets” (see DGE 2016, pp. 945–46).

5 More specifically, the tasks include “cleaning, restocking supplies and performing basic maintenance in apartments, houses, kitchens, hotels, offices and other buildings; washing cars and windows; helping in kitchens and performing simple tasks in food preparation; delivering messages or goods; carrying luggage and handling baggage and freight; stocking vending machines or reading and emptying meters; collecting and sorting refuse; sweeping streets and similar places; performing various simple farming, fishing, hunting or trapping tasks performing simple tasks connected with mining, construction and manufacturing including product-sorting; packing and unpacking produce by hand and filling shelves; providing various street services; pedalling or hand-guiding vehicles to transport passengers and goods; driving animal-drawn vehicles or machinery” (see DGE 2016, pp. 1482–83).

6 My computations from the PLFS of 2022–23 show that the average wage/salary earnings from regular wage/salaried employment among the regular wage/salaried female employees in rural areas was Rs 7,770 per month in Division 6 and Rs 6,492 per month in Division 9. In other words, the difference in monthly earnings was not significant for workers across these two Divisions.

7 There is an outstanding issue of the taxes on natural gas, which is an input in fertilizer production. At present, natural gas is not under GST. But States charge a VAT or a sales tax on natural gas, which ranges from 3 per cent to 25 per cent across States. There have been complaints of cascading taxes (or double levy) here, particularly when natural gas is sold twice in two different States. The issue of bringing natural gas into the GST net and charging 5 per cent tax on it is an undecided matter with the GST Council. In a larger situation of loss of fiscal autonomy for States, States have been hesitant to let go of the VAT or sales tax on natural gas.

References

| Agro-Economic Research Centre (AERC) (2019), “Impact Assessment of Goods and Service Tax (GST) on the Use of Selected Agricultural Inputs in Gujarat,” Report of the AERC, Sardar Patel University, Anand. | |

| Bhalla, S., and Das, T. (2023), “A ‘Jobful’ Economy,” The Times of India, Mar 20, available at https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/blogs/toi-edit-page/a-jobful-economy-2019-22-saw-indias-fastest-ever-phase-of-employment-growth-with-women-being-the-main-beneficiaries/, viewed on July 11, 2024. | |

| Bhalla, S. (2024), “Good Quality or Bad, Data Always Has Plenty to Reveal: Let Data Speak,” Livemint, Apr 19, available at https://www.livemint.com/opinion/online-views/good-quality-or-bad-data-always-has-plenty-to-reveal-let-data-speak-11713443236433.html, viewed on July 11, 2024. | |

| Bharadwaj, S. (2018), “Rural Wage Growth No Less Important than Doubling Farmers’ Income,” press release, India Ratings, Mumbai. | |

| Das, A., and Usami, Y. (2024), “Downturn in Wages in Rural India,” Review of Agrarian Studies, vol. 13, no. 2, pp. 4–28. | |

| Das, A., and Usami, Y. (2017), “Wage Rates in Rural India, 1998–99 to 2016–17,” Review of Agrarian Studies, vol. 7, no. 2, pp. 4–38. | |

| Directorate General of Employment (DGE) (2016), National Classification of Occupations- 2015, Directorate General of Employment, Ministry of Labour and Employment, Government of India, New Delhi. | |

| Government of India (2011), Report of the Working Group on Consumer Affairs, Government of India, New Delhi. | |

| Government of India (2024), The Indian Economy: A Review, Department of Economic Affairs, Ministry of Finance, Government of India, New Delhi. | |

| IANS (2021), “SKM Sends List of 702 Farmers Who Died During Protest,” Deccan Herald, Dec 4, available at https://www.deccanherald.com/india/skm-sends-list-of-702-farmers-who-died-during-protest-1057558.html, viewed on July 11, 2024. | |

| Kamra, A. (2022), “Costs of Cultivation and Profitability in Indian Agriculture: A Plot-level Analysis,” in Ramakumar, R. (ed.), Distress in the Fields: Indian Agriculture After Economic Liberalisation, Tulika Books, New Delhi. | |

| Manoj, C. G. (2021), “PM Modi Says Reforms Here to Stay, Can Fix Loose Ends: ‘MSP Was, Is, Will Be’,” The Indian Express, Feb 9, available at https://indianexpress.com/article/india/narendra-modi-agricultural-reforms-farm-laws-msp-7180431/, viewed on July 11, 2024. | |

| Ramakumar, R. (2018), “A Nation in the Queue: On How Demonetisation Wrecked the Economy and Livelihoods in India,” in Ramakumar, R. (ed.), Note-Bandi: Demonetisation and India’s Elusive Chase for Black Money, Oxford University Press, New Delhi. | |

| Ramakumar, R. (2019a), “Unemployment: Why Amitabh Kant and Surjit Bhalla are Wrong,” NewsClick, April 15, available at https://www.im4change.org/latest-news-updates/unemployment-why-amitabh-kant-and-surjit-bhalla-are-wrong-r-ramakumar-4686987.html, viewed on July 11, 2024. | |

| Ramakumar, R. (2019b), “Crumbs for Farmers,” Frontline, vol. 36, no. 4, 16 February–1 March. | |

| Ramakumar, R. (2022a), “Introduction: Economic Reforms and Agricultural Policy in India,” in Ramakumar, R. (ed.), Distress in the Fields: Indian Agriculture After Economic Liberalisation, Tulika Books, New Delhi. | |

| Ramakumar, R. (2022b), “India’s Agricultural Economy During the Covid-19 Lockdown: An Empirical Assessment,” Indian Journal of Agricultural Economics, vol. 77, no. 1, January–March. | |

| Rashid, O., and Singh, V. (2021), “Four Farmers Killed as Car in Union Minister’s Convoy Runs Amok in Uttar Pradesh,” The Hindu, Oct 3, available at https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/other-states/farmers-killed-as-car-in-union-ministers-convoy-runs-amok/article36807735.ece, viewed on July 11, 2024. | |

| Reserve Bank of India (2017), “Macroeconomic Assessment of Demonetisation: A Preliminary Assessment,” Reserve Bank of India, Mumbai, March 10. | |

| Scroll Staff (2021), “Farmers Call Off Protest in Haryana After State Announces Probe into Baton-charge Incident,” Scroll, Sep 11, available at https://scroll.in/latest/1005149/farmers-call-off-protest-in-haryana-after-state-announces-probe-into-baton-charge-incident, viewed on July 11, 2024. | |

| Varma, G. (2014), “Narendra Modi Promises Higher Support Price to Farmers,” Livemint, Apr 15, available at https://www.livemint.com/Politics/bYMbXRsL3eYQw2Bp4iMaXI/Narendra-Modi-promises-higher-support-price-to-farmers.html, viewed on July 11, 2024. |

Date of submission of manuscript: May 15, 2024

Date of acceptance for publication: June 15, 2024