ARCHIVE

Vol. 13, No. 1

JANUARY-JUNE, 2023

Editorial

Research Articles

Research Notes and Statistics

Interviews

Book Reviews

Referees

The Corporate Sector and Indian Agriculture Under Liberalisation

* Professor, Centre for Economic Studies and Planning, School of Social Sciences, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi, surajitmazumdar@mail.jnu.ac.in.

https://doi.org/10.25003/RAS.13.01.0003

Abstract: The neoliberal agricultural reform agenda that emerged out of the post-1991 liberalisation of the Indian economy had a significant impact on the sector. In contrast to the other sectors of the economy, however, direct corporate takeover of agricultural production is conspicuous by its absence. Even the penetration achieved through corporate presence in agriculture-linked sectors is far from complete, and Indian agriculture also remains mainly oriented to the domestic economy. However, the limits to these processes, the changed context within agriculture, and the prolonged crisis of accumulation of Indian capitalism may be creating conditions for a sharpening of the conflict over the distribution of the value created in agriculture between the peasantry and capital, Indian as well as foreign.

Keywords: India, neoliberalism and agriculture, corporate sector, globalisation, crisis, corporate agriculture, national accounts data

Introduction

The liberalisation process that took place, more comprehensively after 1991 than in the 1980s, inserted Indian capitalism into the process that has come to be called globalisation, with which neoliberalism came to be a worldwide ruling ideology. Private corporate and foreign capital acquired a more privileged status in the new policy paradigm of Indian capitalist development. A new agricultural “reform” agenda that reflected the general thrust of the new neoliberal policy mindset also emerged and captured the minds of the policy-making establishment (Ramakumar 2014, 2022). The emphasis here was on the promotion of privatisation, financialisation, and corporatisation of different stages of Indian agriculture incorporated into global value chains. Trade liberalisation, opening up trade in agricultural commodities to international agribusiness and speculation, and contract farming were promoted as instruments of improving the productivity and efficiency of the agricultural sector.

However, the actual trajectory of developments in the agrarian sector over three decades did not quite follow the script that the dominant worldview dictated. In marked contrast to what has happened in other sectors of the economy, increased corporate penetration of Indian agriculture never took the form of a greater presence in the sphere of agricultural production. If corporate penetration has still increased in the last three decades, it is by means of greater corporate control and dominance of non-agricultural sectors that are part of the agricultural value chain. Similarly, while Indian agriculture may have become more exposed to the vagaries of the international trade in agricultural commodities, it has not significantly changed the fact of a high degree of self-sufficiency in agricultural production or that the bulk of that production continues to be absorbed within India. These outcomes, however, are neither independent of the neoliberal turn of Indian policy-making and nor do they represent the attainment of some kind of equilibrium between the conflicting interests of the working people and domestic and international big capitalist interests. Instead, after three decades of capitalist development in the context of globalisation, these contradictions may in fact be becoming sharper.

Indian Agriculture in the Global Economy

India has always had the basis for being a very important component of the global agricultural economy. The country’s land area is only 2.3 per cent of the global total. Its share in forest and agricultural land in the world are also low, at 1.8 and 3.8 per cent respectively (FAO 2021). However, most of the latter is on account of India’s miniscule share, just 0.32 per cent, of land under permanent meadows and pastures. On the other hand, India accounts for close to 12 per cent of the world’s arable land and nearly 11 per cent of crop land. It is home to the largest cattle population in the world, with its share in the global total being in excess of 30 per cent. When these are combined with India being the second most populous country in the world — home to just under 18 per cent of the world’s population. India is positioned to be both a major producer as well as a large market for agricultural commodities, though its relative importance varies from commodity to commodity.

The very nature of agriculture is that its global production has never been marked by a geographical concentration comparable to the geographical concentration in manufacturing. In the early 1990s, the advanced economies accounted for almost three quarters of world manufacturing value added while their same share in agriculture was a little over a third. However, the geographical distribution of manufacturing and agricultural value added have moved along similar lines during the era of globalisation — a significant reduction in the share of the advanced capitalist economies and a rise in the share of developing countries, particularly in Asia, with China being the standout country (Table 1). India has also increased its share of world agriculture, though much more modestly than China. India, along with Africa, remains among the regions whose share of world value added is still some distance from its position in world population. India’s share of the total value added in agriculture and related activities, was 7.4 per cent in 1990-92, while the share of the advanced capitalist countries was 36.4 per cent (Table 1). By 2018-20, India’s share climbed to 12.8 per cent, while the share of the advanced capitalist countries fell to 14.3 per cent. The gap is even greater in respect of the share of India in agricultural employment, which is almost 23 per cent of the world total. Yet, Indian agriculture’s size has increased from just above a fifth of the aggregate of all advanced economies in the early 1990s to almost attaining parity with it.

Table 1 Distribution of world agricultural value added and population, by region, 1990-2021 three-year averages of percentage shares

| Country or Region | Share of world value added in agriculture, hunting, forestry, fishing | Share of world population | ||||||

| 1990-92 | 2000-02 | 2010-12 | 2018-20 | 1990-92 | 2000-02 | 2010-12 | 2019-21 | |

| Japan | 6.9 | 5.8 | 2.3 | 1.5 | 2.3 | 2.1 | 1.8 | 1.6 |

| Northern America | 9.5 | 10.2 | 6.9 | 5.7 | 5.2 | 5.1 | 4.9 | 4.7 |

| Northern Europe | 4.2 | 3.0 | 1.7 | 1.4 | 1.7 | 1.5 | 1.4 | 1.4 |

| Western Europe | 7.7 | 6.1 | 3.6 | 2.8 | 3.3 | 2.9 | 2.7 | 2.5 |

| Southern Europe | 8.2 | 6.2 | 3.5 | 2.9 | 2.7 | 2.3 | 2.2 | 2.0 |

| Total of Above (Advanced) | 36.4 | 31.3 | 18.0 | 14.3 | 15.2 | 13.9 | 13.0 | 12.2 |

| Eastern Europe | 9.9 | 3.7 | 4.0 | 3.2 | 5.7 | 4.9 | 4.2 | 3.8 |

| China | 9.4 | 17.1 | 25.0 | 30.7 | 22.0 | 20.9 | 19.6 | 18.5 |

| Eastern Asia excluding Japan and China | 3.1 | 2.7 | 1.4 | 1.3 | 1.7 | 1.6 | 1.5 | 1.4 |

| South-Eastern Asia | 5.4 | 6.4 | 9.4 | 8.7 | 8.4 | 8.6 | 8.6 | 8.6 |

| Southern Asia excluding India | 3.7 | 4.2 | 4.1 | 5.9 | 6.0 | 6.5 | 6.9 | 7.2 |

| India | 7.4 | 9.0 | 10.7 | 12.8 | 16.5 | 17.3 | 17.8 | 17.7 |

| Central Asia | 1.4 | 0.9 | 1.1 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 1.0 |

| Western Asia | 4.3 | 4.4 | 4.4 | 2.9 | 2.8 | 3.0 | 3.4 | 3.6 |

| Total Asia excluding Japan | 34.7 | 44.7 | 56.1 | 63.2 | 58.3 | 58.9 | 58.6 | 58.0 |

| Latin America and the Caribbean | 9.2 | 9.5 | 9.6 | 7.2 | 8.3 | 8.5 | 8.5 | 8.4 |

| Africa | 8.5 | 8.9 | 10.7 | 10.6 | 11.9 | 13.3 | 15.1 | 17.2 |

| Oceania | 1.3 | 1.8 | 1.7 | 1.4 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

Source: UN 2023

While India has been a net exporter of agricultural commodities and while its share of world exports of agriculture has risen, other than in the case of a few commodities like rice, India’s importance in world exports is far from being proportionate to its share in world production (Table 2).

Table 2 India’s share in world exports of agricultural commodities, 1990-2018 in per cent

| Commodity division/group | 1990 | 2000 | 2010 | 2018 |

| Meat and meat preparations | 0.2 | 0.7 | 1.6 | 2.5 |

| Fish, crustaceans, and molluscs, and preparations | 1.6 | 2.7 | 2.4 | 4.4 |

| Cereals and cereal preparations | 0.6 | 1.5 | 3.3 | 6.1 |

| Of which: Rice | 6.4 | 10.2 | 11.3 | 28.1 |

| Vegetables and fruit | 0.8 | 1.3 | 1.3 | 1.4 |

| Sugar, sugar preparations, and honey | 0.1 | 0.9 | 2.4 | 2.9 |

| Coffee, tea, cocoa, spices, and manufactures | 4.0 | 3.4 | 2.8 | 3.4 |

| Feeding stuff for animals | 2.2 | 2.3 | 3.6 | 2.0 |

| Tobacco and tobacco manufactures | 0.8 | 0.7 | 2.5 | 2.2 |

| Oilseeds and oleaginous fruit | 0.8 | 1.7 | 1.6 | 1.4 |

Source: Economic Survey 2021-22

Table 3 also shows that the overall significance of foreign trade, both exports and imports, to India’s domestic agricultural production remains low. Much of Indian agricultural production is still used or consumed within India, and the country’s requirements for agricultural commodities are also largely met by domestic production. This overall picture is not, of course, the same across all commodities; there are commodities like pulses and oilseeds where import dependence is high and others like fibre crops, tea, coffee, spices, and even cereals, in whose cases a significant part of production is exported (Table 4). These patterns, however, are not all entirely new and certainly do not indicate that India has moved in the direction of an extremely high degree of specialisation in the production of agricultural commodities as a consequence of its incorporation into a globalised agricultural production system.

Table 3 India’s exports and imports as percentage of gross output of Indian agriculture, 2011-12 to 2020-21 in per cent

| Year | Agricultural imports | Agricultural exports |

| 2011-12 | 3.6 | 9.4 |

| 2012-13 | 4.4 | 10.3 |

| 2013-14 | 3.4 | 10.4 |

| 2104-15 | 4.4 | 8.8 |

| 2015-16 | 4.9 | 7.4 |

| 2016-17 | 5.1 | 7.0 |

| 2017-18 | 4.3 | 7.1 |

| 2018-19 | 3.6 | 7.2 |

| 2019-20 | 3.5 | 6.0 |

| 2020-21 | 3.4 | 6.9 |

Table 4 Value of trade relative to value of output, 2018-19 to 2020-21 in per cent

| Commodity | Exports | Imports |

| Cereals | 10.0 | 0.3 |

| Pulses | 1.4 | 8.1 |

| Oilseeds | 13.3 | 43.9 |

| Sugars | 6.6 | 7.0 |

| Fibres | 13.7 | 6.4 |

| Drugs and narcotics (tea, coffee, tobacco, etc.) | 32.6 | 6.4 |

| Condiments and spices | 18.8 | 0.0 |

| Fruit and vegetables | 2.4 | 3.8 |

| Livestock | 1.5 | 0.0 |

| Fishing and aquaculture | 17.7 | 0.5 |

Corporate Penetration of Indian Agriculture

The expression “corporate penetration of agriculture” can be used in narrow or broad senses. In the narrowest sense, it is the proportion of agricultural production that is undertaken by corporate enterprises. Corporate penetration of Indian agriculture of this kind has always been and remains extremely low. As Table 5 shows, whether we consider the value of gross output or gross value added as indicators of production, Indian agriculture and its different components are overwhelmingly dominated by what is called the “household sector,” which in this case mostly means the aggregate of household agricultural holdings. The share of the private corporate sector remains almost insignificant. This is also reflected in investment or capital formation in agriculture, where even the public sector has much greater significance than the private corporate sector.

Table 5 Distribution of agricultural output and value added by institutional sector, 2011-12 and 2020-21 percentage shares

| Gross output | |||||||

| 2011-12 | 2020-21 | ||||||

| Activity | Public sector | Private corporate sector | Household sector | Public sector | Private corporate sector | Household sector | |

| A | Agriculture, forestry, and fishing | 2.6 | 2.8 | 94.7 | 1.9 | 2.8 | 95.3 |

| A.1 | Crops | 3 | 3.2 | 93.8 | 2.4 | 3.8 | 93.8 |

| A.2 | Livestock | 0 | 1.6 | 98.4 | 0 | 0.6 | 99.4 |

| A.3 | Forestry and logging | 8 | 0.3 | 91.7 | 7.7 | 0.1 | 92.1 |

| A.4 | Fishing and aquaculture | 0.6 | 7.9 | 91.4 | 0 | 8.3 | 91.7 |

| Gross value added | |||||||

| 2011-12 | 2020-21 | ||||||

| Activity | Public Sector | Private Corporate Sector | Household Sector | Public Sector | Private Corporate Sector | Household Sector | |

| A | Agriculture, forestry, and fishing | 2.8 | 2.4 | 94.8 | 1.9 | 2.4 | 95.7 |

| A.1 | Crops | 3.3 | 3.5 | 93.2 | 2.4 | 4.1 | 93.5 |

| A.2 | Livestock | 0 | 0.4 | 99.6 | 0 | 0.1 | 99.9 |

| A.3 | Forestry and logging | 7.5 | 0.1 | 92.4 | 7.6 | 0 | 92.3 |

| A.4 | Fishing and aquaculture | 0 | 1.4 | 98.6 | 0 | 1.3 | 98.7 |

| Gross fixed capital formation | |||||||

| 2011-12 | 2020-21 | ||||||

| Activity | Public Sector | Private Corporate Sector | Household Sector | Public Sector | Private Corporate Sector | Household Sector | |

| A | Agriculture, forestry, and fishing | 13.3 | 0.9 | 85.8 | 17.0 | 0.7 | 82.3 |

| A.1 | Crops | 14.4 | 0.7 | 84.9 | 18.4 | 0.6 | 81.1 |

| A.2 | Livestock | 0.0 | 2.7 | 97.3 | 0.0 | 1.0 | 99.0 |

| A.3 | Forestry and logging | 94.0 | 1.3 | 4.7 | 88.0 | 1.5 | 10.5 |

| A.4 | Fishing and aquaculture | 0.1 | 3.2 | 96.8 | 0.0 | 2.5 | 97.5 |

Source: GoI 2022

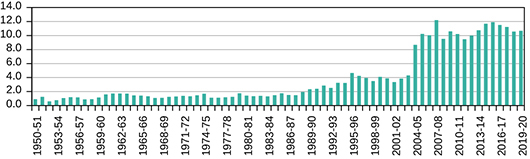

Liberalisation has certainly facilitated a significantly enlarged presence of the private corporate sector in the Indian economy. Data comparability issues do not permit a clear picture of the trend over the past three decades. By the current definition, that is, the definition used for the GDP series with 2011–12 as the base year, the corporate sector now accounts for almost half of Indian economic activity and private interests for more than four-fifths of the corporate sector (Table 6). Figure 1, which shows the long-term trend in the ratio of private corporate savings (retained corporate earnings) to GDP, gives an indication of how dramatic the transformation has been after liberalisation, with the major part of the increase having occurred before 2011–12. Clearly, however, this increased command of the private corporate sector over the economy has been achieved primarily through expansion in non-agricultural activities. The marked difference in corporate presence in agricultural and non-agricultural activities can be seen clearly in Table 7.

Table 6 Share of corporations in selected economic indicators, 2011-12 and 2019-20 in per cent

| Item | Public corporations | Private corporations | All corporations | |||

| 2011-12 | 2019-20 | 2011-12 | 2019-20 | 2011-12 | 2019-20 | |

| Gross value added at basic prices | 10.8 | 8.1 | 33.9 | 37.2 | 44.7 | 45.4 |

| Gross savings | 9.7 | 9.3 | 27.3 | 34.0 | 37.0 | 43.3 |

| Gross capital formation | 11.0 | 11.2 | 36.1 | 37.4 | 47.1 | 48.6 |

Source: GoI 2022

Figure 1 Private corporate savings to GDP1950-51 to 2019-20, in per cent

Source: GoI 2022

Table 7 Share of private corporate sector in national gross output and value added, by sector, 2011-12 to 2020-21 in per cent

| Year | Gross output | Gross value added | ||

| Agriculture | Non-agriculture | Agriculture | Non-agriculture | |

| 2011-12 | 2.8 | 54.5 | 2.4 | 41.1 |

| 2012-13 | 3.0 | 55.0 | 2.6 | 41.6 |

| 2013-14 | 3.1 | 55.5 | 2.5 | 42.1 |

| 2104-15 | 4.0 | 56.2 | 2.9 | 43.8 |

| 2015-16 | 3.6 | 56.1 | 2.7 | 44.9 |

| 2016-17 | 3.4 | 56.4 | 2.7 | 45.4 |

| 2017-18 | 3.1 | 55.6 | 2.6 | 44.9 |

| 2018-19 | 3.0 | 56.6 | 2.6 | 44.9 |

| 2019-20 | 2.8 | 56.0 | 2.3 | 44.9 |

| 2020-21 | 2.8 | 56.4 | 2.4 | 45.4 |

Source: GoI 2022

On the other side, agriculture directly constitutes only a small part of the corporate sector’s presence in the Indian economy. The different variables included in Table 8 can serve as direct or proxy indicators for different dimensions of the scale of private corporate activity (capital investment, production and value creation, employment, and surplus generation). The distribution of each variable among different sectors shows uniformly that while a distinct rise in the importance of non-manufacturing activities has accompanied private corporate expansion after liberalisation, agriculture has remained largely peripheral to that process.

Table 8 Individual economic activities as a share of all activities of the private corporate sector, 2011-12 and 2019-20 in per cent

| 2011-12 | ||||||

| Economic Activity | Gross output | Intermediate consumption | Gross value Added | Consumption of fixed capital | Compensation of employee | Operating Surplus |

| Agriculture, forestry, and fishing | 0.6 | 0.3 | 1.3 | 0.2 | 2.9 | 0.8 |

| Mining and quarrying | 1.6 | 1.7 | 1.4 | 3.5 | 0.3 | 1.3 |

| Manufacturing | 60.3 | 69.8 | 40.0 | 53.7 | 27.7 | 43.1 |

| Electricity, gas, water supply and other utility services | 2.2 | 2.5 | 1.7 | 4.3 | 0.8 | 1.6 |

| Construction | 6.0 | 6.6 | 4.5 | 8.0 | 4.0 | 3.8 |

| Trade, repair, hotels and restaurants | 6.7 | 3.6 | 13.4 | 7 | 11.7 | 15.7 |

| Transport, storage, communication & services related to broadcasting | 6.6 | 6.5 | 6.9 | 7.4 | 6.7 | 6.8 |

| Financial services | 4.0 | 1.9 | 8.4 | 1.0 | 6.2 | 11.3 |

| Real estate, ownership of dwelling and professional services | 8.4 | 4.7 | 16.2 | 5.5 | 30.6 | 11.4 |

| Other services | 3.6 | 2.4 | 6.2 | 9.4 | 9.2 | 4.1 |

| Total Services | 29.3 | 19.1 | 51.1 | 30.3 | 64.4 | 49.3 |

| Total | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| 2019-20 | ||||||

| Economic Activity | Gross output | Intermediate consumption | Gross value Added | Consumption of fixed capital | Compensation of employee | Operating Surplus |

| Agriculture, forestry & fishing | 0.7 | 0.4 | 1.1 | 0.3 | 3.1 | -0.1 |

| Mining & quarrying | 0.9 | 0.9 | 0.8 | 2.1 | 0.2 | 0.9 |

| Manufacturing | 54 | 67.1 | 32.1 | 35.7 | 22.3 | 38.2 |

| Electricity, gas, water supply, and other utility services | 2.2 | 2.3 | 2.0 | 5.6 | 0.5 | 2.2 |

| Construction | 5.1 | 6.0 | 3.6 | 6.0 | 2.5 | 3.5 |

| Trade, repair, hotels, and restaurants | 8.5 | 4.7 | 14.8 | 6.3 | 10.8 | 20.3 |

| Transport, storage, communication, and services related to broadcasting | 6.7 | 6.7 | 6.6 | 14.7 | 5.9 | 4.8 |

| Financial services | 4.7 | 2.4 | 8.4 | 1.8 | 6.6 | 11.7 |

| Real estate, ownership of dwelling and professional services | 12.8 | 6.9 | 22.6 | 20.8 | 37.6 | 12.1 |

| Other services | 4.6 | 2.5 | 7.9 | 6.7 | 10.5 | 6.4 |

| Total Services | 37.3 | 23.2 | 60.3 | 50.3 | 71.4 | 55.3 |

| Total | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

Source: GoI 2022

It would, however, be incorrect for two reasons to conclude from this evidence and the long-term trend of decline in the share of agriculture in India’s GDP that corporate penetration of Indian agriculture is a non-issue.

First, the fact that the corporate capture of the value created in Indian agriculture has so far remained extremely low also means that the potential or scope for extending such capture is now much greater in agriculture than in several non-agricultural activities. For instance, the share of manufacturing in the Indian economy’s gross value added is also declining, and its current levels are almost the same as the value added in the crop production and livestock sectors. However, the private corporate sector already accounts for almost 81 per cent of the value added in manufacturing, so from the point of view of enlarging the share of the corporate sector in the economy, agriculture may be more important than manufacturing. On the other hand, at the international level, the significance of Indian agriculture, particularly its significance relative to advanced economies, has also increased.

Secondly, the agricultural sector also has important backward and forward inter-linkages with other sectors of the economy, which implies channels of increased corporate penetration of agriculture in a broader sense. Agriculture is part of value chains that link it to several non-agricultural activities and draw it into domestic and global circuits of capital. Corporate presence, including the presence of international firms, in these other activities is not only possible but also a reality. In some cases, such presence has a long history, while in others it is relatively recent and has grown as part of the general tendency towards an increased role for private corporate enterprises in non-agricultural activities. In some of these activities, private corporate firms are dominant players, and in others, their presence has been more limited or shared with the public, cooperative and non-corporate private sectors, or with small and medium-sized enterprises. Such corporate presence in agriculture and agriculture-linked value chains also means market interaction between large capitalist business enterprises (as sellers and buyers) on the one hand and a large number of dispersed farmers on the other. Consolidation of corporate control in these agriculture-linked sectors and increased concentration of control in them carries within itself the potential to make for significant corporate influence over production and technology decisions in agriculture and over the prices of agricultural products and inputs. Such corporate control also creates the conditions for corporate appropriation of value created in agriculture at the expense of those who labour in the sector (by increasing input costs and reducing the prices realised by farmers), or those who are the ultimate consumers of the products.

Agriculture uses inputs and machinery that are produced by non-agricultural enterprises and may also be imported. Indeed, Indian agriculture’s global importance as a producer also makes it a large market for agricultural inputs and machinery. Over the long term, the share of parts acquired through market purchases has increased. The values of the quantities used, and therefore the potential size of the market that is currently created, by the crop segment of Indian agriculture, can be seen in Table 9.

Table 9 Values of inputs and fixed capital formation in the crop sector, 2019-20 and 2020-21 in crores of rupees

| Item | 2019-20 | 2020-21 |

| Value of input | 343,448 | 366,031 |

| Seed | 51,630 | 58,756 |

| Organic manure | 42,935 | 46,920 |

| Chemical fertilizers | 57,569 | 66,450 |

| Current repairs, maintenance of fixed assets, and other operational costs | 20,944 | 22,853 |

| Livestock feed | 33,904 | 31,691 |

| Irrigation charges | 5,753 | 7,866 |

| Market charges | 73,595 | 77,820 |

| Electricity | 17,204 | 17,812 |

| Pesticides and insecticides | 2,500 | 2,610 |

| Diesel oil | 37,415 | 33,253 |

| Financial Intermediation Services Indirectly Measured (FISIM) | 93,589 | 100,752 |

| Gross Fixed Capital Formation (GFCF) | 358,113 | 404,807 |

| Of which: Machinery and equipment | 110,174 | 116,384 |

Note: 1 crore = 10 million

Source: GoI 2022

India accounted for 15.37 per cent of the world’s consumption of inorganic fertilizers in 2019 (FAO 2021). Post-liberalisation fertilizer policies, in particular the strangulation of the public sector (Ramakumar 2022), have only made for a continuing and rising dependence on imports (Table 10). The share of the private sector in the domestic production of fertilizers has tended to stagnate for the last two decades — in 2019-20, this share was 43.7 per cent in the case of urea, 54.4 per cent in DAP, and 57.9 per cent in the case of complex fertilizers (Lok Sabha Secretariat 2021). Efforts are being made to create an even more conducive environment for enlarging these shares.

Table 10 Share of imports in consumption of fertilizers in India, by nutrient category, 1981-82 to 2020-21 in per cent

| Period | N | P | K | Total |

| 1981-82 to 1990-91 | 14.1 | 23.6 | 98.4 | 25.0 |

| 1991-92 to 2000-01 | 10.9 | 21.3 | 98.0 | 20.8 |

| 2001-02 to 2010-11 | 15.4 | 26.1 | 99.6 | 28.0 |

| 2011-12 to 2020-21 | 26.1 | 36.7 | 92.2 | 35.0 |

Source: GoI 2023

The comparatively low levels of mechanisation in Indian agriculture make India a market for farm machinery with considerable growth potential, and within agricultural investment, the share of expenditure on machinery and equipment is increasing. India and China are already the two largest tractor markets in the world (Machinery World 2018). Indian business groups have been major players in this industry for decades. The top four Indian companies account for almost 80 per cent of sales in the Indian tractor market (Tractor Junction 2021). Mahindra is the number one manufacturer of tractors in the world, and several other Indian companies also find a place among the top companies worldwide (Tractor Junction 2023). Foreign firms from the same list, like John Deere and New Holland, also have an important presence in the Indian market.

India is also the world’s fifth-largest seed market, increasing its share in the world market for seeds from four per cent in 2012 to six per cent in 2019 (NSAI 2020). It is another sector being eyed by global and Indian players as a market with significant scope for growth through the promotion of an increase in seed replacement rates, which are still relatively low in India. The private sector’s presence in the Indian seed industry increased significantly after the 1988 policy. It had, however, started declining somewhat in the first decade of the century; by 2009-10, it had fallen below 40 per cent from above 47 per cent in 2003-4 (Singh, Kumar, and Jatwa 2019). It picked up again in the second decade, and by 2021-22, the private sector's share in aggregate domestic seed supply had reached almost 67 per cent (Table 11). Indian as well as multinational seed companies are active in promoting the use of their seeds.

Table 11 Share of private sector in availability of certified/quality seeds, by crop group, by selected crops, 2021-22 in per cent

| Crop name | Private share |

| Total cereals | 61.1 |

| Wheat | 63.1 |

| Rice | 56.5 |

| Maize | 71.8 |

| Pearl millet | 89.7 |

| Sorghum | 68.3 |

| Total fibre | 52.6 |

| Cotton | 59.0 |

| Jute/Mesta | 24.1 |

| Total pulses | 41.5 |

| Gram | 34.8 |

| Black gram | 47.2 |

| Mung | 42.4 |

| Horse gram | 62.5 |

| Lentil | 35.2 |

| Peas | 69.9 |

| Pigeon pea | 54.4 |

| Kidney bean | 100.0 |

| Total oilseeds | 54.7 |

| Castor | 91.3 |

| Rapeseed/Mustard | 46.4 |

| Groundnut | 43.7 |

| Sesame | 73.1 |

| Soybean | 65.3 |

| Potato | 98.6 |

| Fodders | 40.6 |

| Grand total | 66.8 |

Source: GoI 2023.

In the case of agrochemicals, too, an important Indian and foreign private-sector-dominated industry exists, and concerted efforts are under way here also to increase the levels of consumption of such agrochemicals by Indian agriculture. A fragmented industry structure in India is gradually changing, in parallel to a global trend of consolidation, and the top 11 firms — a mix of Indian and foreign companies — accounted for 86 per cent of the market in 2020–21 (Binani 2021).

Additionally, the increasing importance of financial intermediation services take the form of implicit charges (captured in Table 9). These have grown from less than one per cent of the value of crop output at the beginning of the 1990s to over 2.5 per cent three decades later.

The long-term changes in Indian agriculture have also affected the other side of agriculture: the proportion of agricultural production in India that is now marketed rather than directed towards self-use has become very high across all commodities. Table 12 illustrates the levels this proportion has attained for a range of agricultural commodities.

Table 12 Marketed Surplus Ratio (MSR) of selected crops, 2014-15, in per cent

| Crop/Group | MSR |

| Cereals | |

| Rice | 84.35 |

| Wheat | 73.78 |

| Maize | 88.06 |

| Sorghum | 66.64 |

| Pearl millet | 68.42 |

| Barley | 77.67 |

| Finger millet | 48.92 |

| Pulses | |

| Pigeon pea | 88.21 |

| Gram | 91.10 |

| Black gram | 92.25 |

| Mung | 90.65 |

| Lentil | 94.38 |

| Oilseeds | |

| Groundnut | 91.63 |

| Rapeseed and Mustard | 90.94 |

| Soybean | 97.60 |

| Sunflower | 100.00 |

| Sesame | 95.37 |

| Safflower | 100.00 |

| Niger | 97.78 |

| Other commercial crops | |

| Sugarcane | 85.37 |

| Cotton | 98.79 |

| Jute | 98.59 |

| Vegetables | |

| Onion | 91.29 |

| Potato | 89.54 |

Source: GoI 2018.

Further processing in non-agricultural enterprises, which consume these crops as inputs, precedes the final use of the marketed surplus of several agricultural commodities. The division of the output between the part that is consumed as input in other sectors and the part that is directly consumed or exported without significant further processing varies significantly across agricultural commodities (Table 13). Commercial crops like cotton, sugarcane, and tea naturally have most of their outputs used up as inputs in other sectors, and their corresponding manufacturing industries have existed in India since the mid-19th century. Many top Indian business groups began their histories in these sectors, and several still have a presence in them. Processing industries with a big business presence have also been important in the case of several oilseeds. Even in the case of cereals and pulses, a significant part enters consumption through processing in mills, and the corporate presence is increasing in mills too. In other food crops as well as in livestock products, although the processing component may still be low, it is increasing steadily, and the participation of Indian firms and MNCs is growing. Several major Indian business groups — including Tata, Adani, Bajaj, ITC, Wadia (Britannia), Murugappa (EID Parry), Godrej, and Triveni Engineering — and MNCs like Hindustan Lever and Nestlé — have operations in agriculture-linked industries functioning as important parts of their business portfolios.

Table 13 Supply and use of agricultural products, 2018-19, in percentage shares

| Product industry | Supply and use at PP(in Crores) | Supply distribution | Use distribution | ||||||

| Output at producer price | Final import | Trade and transport margins | Inter-industry consumption in agriculture | Inter-industry consumption by non-agriculture | PFCE | CIS | Export | ||

| Paddy | 360739 | 84.4 | 0 | 15.6 | 1.2 | 45.7 | 39.5 | 0.7 | 12.9 |

| Wheat | 238725 | 82.6 | 0 | 17.4 | 2.8 | 50.5 | 45.1 | 1.3 | 0.2 |

| Coarse cereals | 98081 | 76.4 | 0.5 | 23.1 | 1.9 | 33.3 | 61.7 | 0.7 | 2.3 |

| Gram | 57778 | 83.2 | 0 | 16.8 | 4.2 | 44.1 | 51.1 | 0.6 | 0 |

| Pigeon pea | 18965 | 84.8 | 0 | 15.2 | 1.2 | 36.4 | 61.7 | 0.7 | 0 |

| Other pulses | 52084 | 81.1 | 0 | 18.9 | 7.5 | 48.7 | 42.0 | 1.7 | 0 |

| Groundnut | 38462 | 82.1 | 0 | 17.9 | 4.9 | 18 | 76.9 | 0.2 | 0 |

| Rapeseed and mustard | 41636 | 88.7 | 0 | 11.3 | 0.8 | 75.5 | 22.9 | 0.5 | 0.3 |

| Other oilseeds | 79956 | 77.3 | 2.7 | 19.9 | 2.1 | 72.8 | 17.2 | 1.9 | 6 |

| Kapas/cotton | 95681 | 81.6 | 0 | 18.4 | 1.2 | 98 | 0 | 0.8 | 0 |

| Jute, hemp, and mesta | 10788 | 79.1 | 6.9 | 14.1 | 0.4 | 93.9 | 0 | 4.5 | 1.2 |

| Sugarcane | 173905 | 72.4 | 0 | 27.6 | 0.9 | 69.5 | 27.9 | 1.7 | 0 |

| Coconut | 29137 | 84.7 | 0.3 | 15 | 2.5 | 12.8 | 83.7 | 0.2 | 0.8 |

| Tobacco | 13136 | 72.3 | 0 | 27.7 | 1.5 | 30.7 | 67.8 | 0.1 | 0 |

| Tea | 22802 | 77.5 | 0 | 22.5 | 2.7 | 95 | 0 | 2.4 | 0 |

| Coffee | 14250 | 76.5 | 4.5 | 19.1 | 1.8 | 70.4 | 0 | 2.2 | 25.6 |

| Rubber | 11717 | 71.6 | 0 | 28.4 | 0 | 96.8 | 0 | 3.2 | 0 |

| Fruits | 425171 | 68.3 | 6.6 | 25.1 | 1.0 | 10.1 | 86.5 | 0.1 | 2.2 |

| Vegetables | 380987 | 74.1 | 0.2 | 25.6 | 8.9 | 11.8 | 76.6 | 0.3 | 2.4 |

| Other food crops | 515966 | 76.4 | 1.1 | 22.5 | 39.9 | 16.7 | 39.5 | 1.2 | 2.6 |

| Milk | 870236 | 89.1 | 0 | 10.9 | 0.5 | 31.5 | 67.6 | 0.4 | 0 |

| Wool | 3220 | 14.4 | 72.2 | 13.4 | 0 | 86.1 | 0 | 11 | 2.9 |

| Egg and poultry | 195385 | 79.7 | 0 | 20.3 | 7 | 22.5 | 67.6 | 2.6 | 0.3 |

| Other livestock products | 287474 | 75.8 | 2.2 | 22 | 0.2 | 21.7 | 72 | 0.2 | 3.7 |

| Industry wood | 268870 | 79.5 | 0 | 20.5 | 0.3 | 98.6 | 0 | 1.1 | 0 |

| Firewood | 94222 | 69.4 | 0 | 30.6 | 0 | 1.6 | 97.2 | 1.1 | 0 |

| Other Forestry products | 51018 | 83 | 0.3 | 16.7 | 38.3 | 38.7 | 21.1 | 0.6 | 1.2 |

| Inland fish | 165089 | 83.1 | 0 | 16.9 | 2.4 | 16.5 | 80.7 | 0.3 | 0 |

| Marine fish | 161592 | 72.3 | 0 | 27.6 | 0.7 | 11.7 | 86.7 | 0.8 | 0.1 |

| Agriculture, Forestry, and Fishing | 4777072 | 79.3 | 1.0 | 19.7 | 6.6 | 34.3 | 56.0 | 0.8 | 2.1 |

Note: PP = Producer Price; PFCE = Private Final Consumption Expenditure; CIS = Change in Stocks

Source: GoI 2022.

No matter what the share of the processing part in them is, the marketing of all agricultural commodities involves storage, transport, and trade that are non-agricultural activities and are not typically undertaken by farmers. As Table 13 also indicates, these trade and transport margins account for around a fifth of the prices at which agricultural commodities eventually became available to users. Corporate presence in this segment of the agricultural value chain has not historically been significant, with the public, cooperatives, and unorganised sectors being important at different stages. Efforts to change that picture and enlarge the corporate share of wholesale and retail trade in general and that of agricultural commodities in particular are being made repeatedly. Private corporate players may have had limited success in this area so far, but that does not mean that this part of their agenda has been shelved.

A new element in the agricultural scene is the global finance capital-supported and government-encouraged growth of agri-tech start-ups that make use of digital technologies. Over 1000 such start-ups are reported to be operating in India today. In the two and a half years after January 2020, about 100 agri-tech start-ups raised over USD 1.33 billion in financing (Mantra Labs 2023). What “disruptive” effects (a popular term in the start-up sphere) this new feature may have is an area requiring study.

Agriculture and Indian Capitalism After 1991 and the Emerging Scenario

Production taking place within Third World economies has become an increasingly important domain of intensified exploitation of the working people by domestic capitalists as well as by international capital. At the time liberalisation began, Indian agriculture presented a very distinctive challenge to the globalisation and corporate takeover of the sector. The initial impact of neoliberal reforms — the reduction of state support to agriculture and its increased exposure to global market vagaries — triggered an “agrarian crisis” in the mid-1990s (Patnaik 2003; Ramachandran and Rawal 2010; and Ramakumar 2014). Liberalisation and the agrarian crisis reinforced India’s low-wage conditions; a part of the surplus labour force was pushed out of agriculture without any proportionate creation of opportunities for their absorption in non-agricultural activities. Liberalisation made for the emergence of a permanent, unlimited labour supply situation for capitalist accumulation in non-agricultural activities. This made conditions conducive to wage stagnation, an intensified exploitation of the working class employed in non-agricultural activities, and a correspondingly growing share of surplus incomes in the corporate sector. This is an important mechanism for the growth of inequality in India over the last few decades. These processes also facilitated an unprecedented pace of private corporate accumulation and expansion and its increasing capture of different sectors of the economy. This capture included, but also went beyond, manufacturing, the sector of private corporate capital that has always been the most dominant.

Even though the thrust of state policy continued to aggravate rather than ease the agrarian and employment crises, these crises and their political manifestations also forced concrete responses from the state that, at least in some ways, ran counter to the logic of the globalisation of Indian agriculture, corporate penetration of that sector, and the retreat of the state from the agrarian economy. With agriculture unable to perform to the same extent as earlier in the function of sustaining the labour reserve, the state’s retreat from the agrarian economy and its ability to facilitate corporate takeover were hampered. One stark indicator of this is that the proportion of the food grain output procured by state agencies and of the public distribution system in the net availability of food grain are both significantly greater than was ever the case before 1991 (Table 14). While neoliberal reforms have circumscribed the extent of benefits accruing to farmers (Bansal and Rawal 2020), repeated attempts to bring down the subsidy bill have also proved unsuccessful.

Table 14 Indicators of importance of procurement and public distribution of food grain, 1961 to 2019 in per cent

| Year | Procurement as percentage of net production of foodgrains | Public distribution as per cent of net availability of foodgrain |

| 1961 | 0.7 | 5.3 |

| 1971 | 9.3 | 8.3 |

| 1981 | 11.4 | 11.4 |

| 1991 | 12.7 | 13.1 |

| 2001 | 24.7 | 8.4 |

| 2011 | 30.1 | 23.6 |

| 2019 | 30.7 | 24.0* |

Notes: *Pertains to financial year

Source: Economic Survey 2022-23

Notwithstanding the foregoing, renewed efforts to expand the corporate takeover of Indian agriculture and its globalisation are emerging. The background to this is the crisis of Indian capitalism and globalisation itself. The most significant expression of this in India has been the stagnation in corporate and overall investment for over a decade and a declining trend in the investment ratio (Mazumdar 2021). This prolonged crisis is a reflection of the limits to accumulation through a globalisation strategy that is based on low-wage labour; it can only worsen a crisis that has both economic and political dimensions.

Two of the significant consequences of the crisis in Indian capitalism driving the renewed efforts to implement the neoliberal reform agenda in agriculture are a strengthening of the fiscal constraint and a growing tendency towards parasitism. The latter refers to a state-assisted encroachment on the non-private-corporate sphere of the economy (whether public or private) and acquisitions of other corporate enterprises. The agricultural sector is one of the most important potential targets of such expansion. Indian and international capital seek to open up investment opportunities along the agricultural value chain; capture a greater part of the value created in agricultural production through control over input and output prices; and corner the benefits of government subsidies directed towards the agricultural sector. The now-shelved new farm laws, which required historic struggle to be rolled back, reflect these tendencies and the contradictions to which they give rise.

Conclusion

The fact that Indian agriculture presented a very distinctive challenge to the globalisation and corporate takeover of the economy is reflected in the fact that the corporate takeover of economic activities in the agricultural and non-agricultural sectors has proceeded at very different speeds. Some increase in corporate penetration of agriculture, though, has happened indirectly on account of greater corporate presence in non-agricultural activities that have linkages with agriculture. Even this is, however, far from being complete. On the other hand, the crisis of accumulation in Indian capitalism and the existing limits to corporate takeover of that sector in the past have enhanced the relative importance of agriculture and the agriculture value-chain as a potential direction of future corporate expansion and consolidation. While agricultural production has not been taken over by the corporate sector and may not be in the foreseeable future, changes in the sector may have weakened the capacity of farmers and agricultural workers to act as countervailing forces to corporate penetration of agriculture. The tendency towards increasing corporate penetration into Indian agriculture is also likely to express itself in other ways, that is, by means of corporate – Indian and foreign – intervention in the production and marketing of agricultural inputs, including machinery, and post-harvest corporate intervention in marketing, processing, and agro-industrial production.

References

| Bansal, Prachi, and Rawal, Vikas (2020), “Economic Liberalisation and Fertiliser Policies in India,” Social Scientist, vol. 48, no. 9/10 (568-569), pp. 33-54. | |

| Binani, Himanshu (2021), “Agro Chemicals: Ride on Food Security Tailwinds!” Prabhudas Liladher Agro Chemical Sector Report, Dec 27, available at https://www.plindia.com/resreport/agrochemicals-27-12-21-pl.pdf, viewed on June 27, 2023. | |

| Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) (2021), World Food and Agriculture - Statistical Yearbook 2021, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Rome. | |

| Government of India (GoI) (2018), Agricultural Statistics at a Glance 2017, Ministry of Agriculture and Farmers Welfare, New Delhi, available at https://eands.dacnet.nic.in/PDF/Agricultural%20Statistics%20at%20a%20Glance%202017.pdf, viewed on August 8, 2023. | |

| Government of India (GoI) (2022), National Accounts Statistics 2022, Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation, available at https://www.mospi.gov.in/publication/national-accounts-statistics-2022, viewed on August 8, 2023. | |

| Government of India (GoI) (2023), Agricultural Statistics at a Glance 2022, Ministry of Agriculture and Farmers Welfare, New Delhi. | |

| Lok Sabha Secratariat (2021), Standing Committee on Chemicals & Fertilizers, Demands for Grants 2021-22, Twentieth Report, Seventeenth Lok Sabha, Ministry of Chemicals and Fertilizers (Department of Fertilizers), New Delhi. | |

| Machinery World (2018), “Agricultural Tractors: India and China Have Half of the Global Market,” Jan, available at https://www.mondomacchina.it/en/agricultural-tractors-india-and-china-have-half-of-the-global-market-c1943, viewed on June 27, 2023. | |

| Mader, Philip, Mertens, Daniel, and Zwan, Natascha van der (2020), “Financialization: An Introduction,” in Mader, Philip, Mertens, Daniel, and Zwan, Natascha van der (eds.), The Routledge International Handbook on Financialization, Routledge, Oxford and New York, pp. 1-16. | |

| Mantra Labs (2023), “The Rise of the Agritech Ecosystem in 2023,” Feb 3, available at https://community.nasscom.in/index.php/communities/agritech/rise-agritech-ecosystem-2023, viewed on June 27, 2023. | |

| Mazumdar, Surajit (2021), “The Coronavirus and India’s Economic Crisis: Continuity & Change,” in Rawal, Vikas, Ghosh, Jayati, and Chandrasekhar, C. P. (eds.), When Governments Fail: A Pandemic and its Aftermath, Tulika Books, New Delhi, pp. 184-207. | |

| National Seed Association of India (NSAI) (2020), “Note of Information for the National Seed Association of India (NSAI) Proposal on Capacity Building program Initiatives for Indian Seed Industry as Part of Atma Nirbhar Bharat Program Submitted to NABARD,” Nov 17, available at http://nsai.co.in/storage/app/media/uploaded-files/Detailed%20note%20for%20NABARD.pdf, viewed on June 27, 2023. | |

| Patnaik, U. (2003), “Food Stocks and Hunger: The Causes of Agrarian Distress,” Social Scientist, vol. 31, no. 7/8, pp. 15-41. | |

| Ramachandran, V. K., and Rawal, Vikas (2010), “The Impact of Liberalization and Globalization on India’s Agrarian Economy,” Global Labour Journal, vol. 1, no. 1, pp. 56-91. | |

| Ramakumar, R. (2014), “Economic Reforms and Agricultural Policy in India,” Paper presented at the “Tenth Anniversary Conference of the Foundation for Agrarian Studies,” Kochi, January 9-12. | |

| Ramakumar, R. (2022), “Introduction,” in Ramakumar, R. (ed.), Distress in the Fields: Indian Agriculture After Economic Liberalization, Tulika Books, New Delhi, pp. 1-68. | |

| Singh, Jogendra, Kumar, Vinod, and Jatwa, Tarun Kumar (2019), “A Review: The Indian Seed Industry, Its Development, Current Status, and Future,” International Journal of Chemical Studies, vol. 7, no. 3, pp. 1571-1576. | |

| Tractor Junction (2021), “Tractor Sales Statistics India FY 2021,” Apr 3, available at https://www.tractorjunction.com/tractor-news/tractor-sales-in-india-financial-year-2021/, viewed on June 27, 2023. | |

| Tractor Junction (2023), “Top 10 Tractor Companies in the World – Tractor List 2023,” Mar 7, available at https://www.tractorjunction.com/blog/top-10-tractor-companies-in-the-world-tractor-list/, viewed on June 27, 2023. | |

| United Nations (UN) (2023), National Accounts - Analysis of Main Aggregates (AMA), Statistics Division, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, available at https://unstats.un.org/unsd/snaama/Index, viewed on August 8, 2023. |

Date of submission of manuscript: June 25, 2023

Date of acceptance for publication: July 25, 2023