ARCHIVE

Vol. 13, No. 2

JULY-DECEMBER, 2023

Editorial

Research Articles

Tribute

Book Reviews

Review Article

The National Commission on Farmers, 17 Years On

*Food Systems Specialist, FAO Representation in Bangladesh, bhavjoy@gmail.com

https://doi.org/10.25003/RAS.13.02.0008

Introduction

Professor M. S. Swaminathan was Chairman of the National Commission on Farmers (NCF), a position of the rank of a Cabinet Minister of the Government of India. The NCF was constituted by the Government of India for a two-year term (2004–06). It had a Chairman, two full-time members, a member-secretary, four part-time members, and elaborate terms of reference. There had been commissions on aspects of agriculture earlier; this was the first time, however, that the “farmer” was the centre of focus. Popularly known as the Swaminathan Commission, the NCF submitted five reports under the generic title, “Serving Farmers and Saving Farming,” and a separate draft national policy for farmers. I worked in the NCF as Officer on Special Duty (Technical) to the Chairperson. This paper discusses some of the significant recommendations of the NCF.

MSS set a fast pace of work for the team from the moment he took charge. The official notification from the government regarding the constitution of the Commission was issued in November 2004. Although office infrastructure and logistics were still to be put in place, work began with the objective of submitting the first report of the NCF in December 2004. On December 24, the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami struck, ravaging the lives and livelihoods of coastal communities in India and neighbouring countries. MSS wrote a chapter titled “Beyond Tsunami: Saving Lives and Livelihoods” for the first report, which was submitted a few days later. It recommended short-, medium-, and long-term measures to be taken to alleviate the loss and distress caused by the calamity to farm and fishworker families, and to build resilience to future calamities.

The first report has a chapter titled “A New Deal for Women in Agriculture,” putting on record the recognition by the Commission of the important but often ignored role of women in the sector. When MSS was in the Planning Commission in 1980–82, he introduced, for the first time, a chapter on Women and Development in the Five-Year Plan (this was in the VI Plan, 1980-85). Given that one-third of elected panchayat representatives are women, the NCF proposed a special fund for women in village panchayats (Gram Panchayat Mahila Fund, or GPMF). It recommended that just as Members of Parliament are provided financial resources for development work in their constituencies, the GPMF should be a dedicated fund managed by elected women representatives and used for “community activities that help to meet essential gender-specific needs” (GoI 2004).

Consultative Process

The NCF engaged in consultations right from the beginning with subject experts, research institutes, agricultural universities, Union and State Government officials, the private sector, civil society organisations, and above all, with farmer men and women. In 2005, regional consultations were organised on the theme “Mission 2007: Hunger Free India,” in collaboration with the M. S. Swaminathan Research Foundation (MSSRF) and the United Nations World Food Programme. The suggestions received contributed to the medium-term strategy for food and nutrition security recommended by the NCF. In October 2005, MSS led field trips of the NCF to Punjab and the Vidarbha region of Maharashtra in order to understand the situation on the ground by discussing issues with men and women farmers, besides engaging with government officials, scientists, and others. Recommendations to address the prevailing agrarian crisis were made in the third report of the NCF subtitled “2006: Year of Agricultural Renewal,” and submitted in December 2005. The report called for concurrent attention to soil health management, equity, and efficiency in water use, credit and insurance reform, technology upgradation and dissemination, and farmer-centred marketing, with priority attention to distress hotspots (GoI 2005b).

In April 2006, following the submission of the fourth report (GoI 2006a), which contained the draft national policy for farmers, the draft policy was translated into different languages for discussion. Between May and early September 2006, twenty-one State and regional level consultations were held, seeking comment and suggestions on the draft. Nine more consultations were organised for comments on specific aspects of the draft. MSS himself chaired many of these meetings.

Addressing the Agrarian Crisis

The second report of the NCF, subtitled “From Crisis to Confidence,” recommended a livelihood security compact to alleviate farmers’ distress and suicides (GoI 2005a). It identified the following five factors as the main reasons for farmers’ distress: i) the unfinished agenda in land and asset reform, ii) lack of adequate and timely institutional credit, iii) the quantity and quality of water available for agriculture, iv) technology fatigue and inadequate efforts in education, research, and extension and the consequent drop in factor productivity, and v) the lack of opportunities for assured and remunerative marketing. Far-reaching recommendations were made to ensure the livelihood security of farm men and women. These addressed issues of crop and animal husbandry, harnessing information technology and remote sensing tools to provide block-, district- and State-level land use planning and advisory services, and market reform. The report called for a paradigm shift in mindset, and sought to consider farmers as “guardians of national food security” and partners in agricultural transformation, not just as beneficiaries of government programmes. The report also sought to measure agricultural progress by using the rate of growth in farmer’s income as the indicator of progress. For the cover of the fifth and final report of the Commission, MSS chose to use an extract from the Visitors’ Book of the National Dairy Research Institute, Bangalore, in which Mahatma Gandhi had identified himself as a farmer. In the foreword to the Report, which was signed by all the members of the Commission, MSS wrote: “It is this pride in farming, both as a way of life and means of livelihood, that we should revive” (GoI 2006b).

The Government of India approved a National Policy for Farmers (NPF) that was based on the Commission’s draft policy, and the Ministry of Agriculture, as recommended, was renamed “Ministry of Agriculture and Farmers’ Welfare” (GoI 2007). Another significant recommendation that was not, however, accepted, was to shift agriculture from the State List to the Concurrent List in Schedule VII, Article 246 of the Constitution, under which both States and the Centre could legislate, given that many important policy decisions and allocation of resources are under the purview of the Union government. The report noted that, by

placing agriculture on the Concurrent List, serving farmers and saving farming becomes a joint responsibility of the Centre and States, i.e., a truly national endeavour in raising the morale, prestige and economic well-being of our farm women and men. (GoI 2006b, pp 264)

Many people associate the NCF mainly with its landmark recommendation to fix the minimum support price at 50 per cent above C2 cost of production. The rationale for this recommendation lay in the Commission’s conviction that farmers’ incomes and well-being should be the primary determinant of the pricing formula. MSS wrote that the “Minimum Support Price (MSP) should be at least 50 per cent more than the weighted average cost of production. The ‘net take-home incomes’ of farmers should be comparable to those of civil servants” (GoI 2006b, pp. 245). He also recommended that the Sixth Pay Commission do a background study of the take-home incomes of farmers:

A comparative study of the positions of the salaried class and of the self-employed farmers working in sun and rain . . . is in the broader interest of the nation, particularly in the context of a commitment to inclusive growth. (GoI 2006b, ch. 7, p. 240)

Institutional Reform

Detailed recommendations were made in the first report on the support needed for rainfed farming. A National Rainfed Area Authority was subsequently established in 2006. The third report submitted in December 2005 recommended a National Fisheries Development Board, which was established in late 2006. Other key recommendations included the establishment of a National Livestock Development Council for integrated attention to all aspects of the livestock sector, including breeding, fodder and feed, healthcare, marketing, meat, value addition, and animal energy; and a National Livestock Feed and Fodder Corporation to ensure the availability of quality feed and fodder to ensure adequate and quality nutrition for livestock. In keeping with the focus on farmers, it also recommended that the National Bank for Agriculture and Rural Development (NABARD) be restructured as a 21st-century National Bank for Farmers.

Agriculture Education

The NCF made four important recommendations on agricultural education. The first one was to set up Centres of Excellence in Agriculture (Crop and Animal Husbandry, Fisheries, and Forestry) on the model of the IITs and the IIMs. The second was to mainstream entrepreneurship and business skills in all applied courses, rather than keep business management as a separate course. The third recommendation was to develop a system for farm graduates to provide extension and other services by recognising them as Registered Farm Practitioners on the lines of registration of practitioners in medical and veterinary sciences, and establishing an All India Agricultural Council on the model of the Medical Council and Veterinary Council to give accreditation. The fourth recommendation was that the curricula of agricultural universities sensitise students on the role of women in agriculture. It also recommended that agricultural and rural universities undertake Rural Systems Research (RSR) with concurrent attention to on-farm and non-farm livelihoods. The report called for enlarging the scope of the Krishi Vigyan Kendra to include enterprise development and capacity-building in post-harvest technology and food safety. Such centres were to be renamed Krishi Vigyan aur Udyog Kendra.

Increasing the Competitiveness Of Agriculture

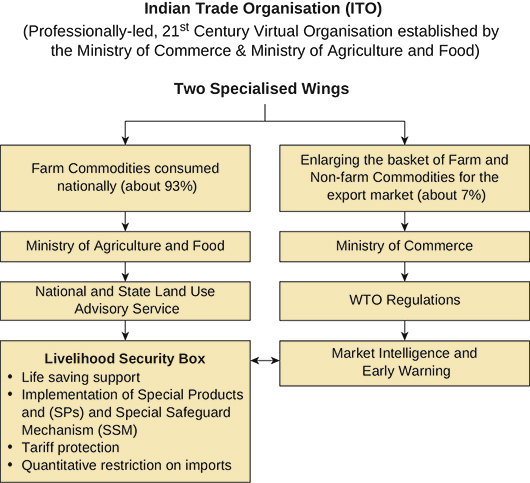

The NCF recommended establishing an Indian Trade Organisation (ITO) and India’s own boxes for domestic agricultural support on the model of the World Trade Organisation’s (WTO) Blue, Green, and Amber Boxes, to protect the interests of our farmers. Given that only a small proportion of Indian goods enter the global market, it proposed the following:

We must segregate the very modest support we extend to our farmers into two groups – those which are of the nature of life- and livelihood-saving support to small farm families, and those which could be considered as trade distorting in the global market. (GoI 2005b, p. 16)

The point was reiterated in the fifth and final report in the chapter on improving the competitiveness of Indian agriculture. Proposed as a virtual body, the ITO was conceptualised as having a wing dealing with commodities that were largely consumed domestically, with a land-use advisory service under it, and another for commodities that targeted the export market and subject to WTO regulations. The proposed schematic diagram of the ITO given in the report is worth re-examining (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Proposed Structure of Indian Trade Organisation

Making Hunger History

The final report presented a medium-term strategy for food and nutrition security. The NCF called for ensuring farmers’ income security through MSP, and food security for the nation through a universal public distribution system (PDS). The cost of subsidy to provide for a universal PDS was computed and found to be just a little over 1 per cent of the Gross Domestic Product, while the benefits would be manifold. It recommended that the government create a national urban employment guarantee programme on the lines of the National Rural Employment Guarantee Act. The Commission suggested that the activities under such a programme could include work related to sanitation, pollution control, tree planting and protection, energy generation from waste, and compost making (GoI 2006b, ch. 2). The report also recommended a National Food Guarantee Act to promote a diversified food basket. The National Food Security Act was enacted in 2013.

Shaping the Economic Destiny of our Farmers

The final and seminal chapter in the final report of the NCF was written entirely by MSS. Titled “Shaping the Economic Destiny of our Farmers,” the concluding section proposed a three-pronged strategy for shaping India’s agricultural future. The gains in the heartland of the Green Revolution had to be defended through promotion of conservation farming and establishing a national agriculture biosecurity system; the gains had to be extended to eastern India and the North Eastern States1; and new gains had to be made in thrust areas such as post-harvest technology, agro-processing and value addition to primary produce (GoI 2006b, Chapter 7).

In Conclusion

Looking back today, 17 years after the term of the NCF ended, it is clear that many of the recommendations provide direction on the way forward.

Suicides by farmers -- in the backdrop of which the NCF was constituted -- continue. According to the National Crime Records Bureau, 5,318 farmers/cultivators and 5,563 agricultural labourers (10,881 in total) committed suicide during 2021, accounting for 6.6 per cent of total suicides (GoI 2022). India has had a committee on Doubling of Farmers’ Income, but fair and remunerative prices for farmers’ produce remains a mirage.

Reflecting on the National Policy for Farmers a decade after its approval, M.S. Swaminathan called for its implementation. He wrote: “Do not measure agricultural progress merely in statistical terms, but mainstream the human dimension in all agricultural programmes and strategies, and use increase in farmers’ real income as the measure of progress.” (Swaminathan 2016) He reiterated that the minimum support price should be fixed at cost plus 50 per cent return. The government would do well to revisit the recommendations of the National Commission on Farmers, adapt them to the changed circumstances, and implement them.

Notes

1 “Bringing Green Revolution to Eastern India” (BGREI) programme was launched in 2010–11 to address the constraints on the the productivity of rice-based cropping systems in eastern India.

References

| Government of India (GoI) (2004), Serving Farmers, Saving Farming, First Report, National Commission on Farmers, Ministry of Agriculture, New Delhi, Dec. | |

| GoI (2005a), Serving Farmers, Saving Farming: Crisis to Confidence, Second Report, National Commission on Farmers, Ministry of Agriculture, New Delhi, Aug. | |

| GoI (2005b), Serving Farmers, Saving Farming, 2006: Year of Agricultural Renewal, Third Report, National Commission on Farmers, Ministry of Agriculture, New Delhi, Dec. | |

| GoI (2006a), Serving Farmers, Saving Farming – Jai Kisan: A Draft National Policy for Farmers, Fourth Report, National Commission on Farmers, Ministry of Agriculture, New Delhi, Apr. | |

| GoI (2006b), Serving Farmers, Saving Farming- Towards Faster and More Inclusive Growth of Farmer’s Welfare, Fifth and Final Report, Vol. 1, National Commission on Farmers, Ministry of Agriculture, New Delhi, Oct. | |

| GoI (2007), National Policy for Farmers, Department of Agriculture and Cooperation, Ministry of Agriculture, New Delhi. | |

| GoI (2022), Accidental Deaths and Suicides in India 2021. National Crime Records Bureau, Ministry of Home Affairs, New Delhi. | |

| Swaminathan. M.S. (2016). “National Policy for Farmers: Ten Years Later,” Review of Agrarian Studies, vol. 6, no. 1, available at http://ras.org.in/202c45ed2cf674e85de6dc907cf1b981 |