ARCHIVE

Vol. 15, No. 1

JANUARY-JUNE, 2025

Editorial

Research Articles

Research Notes and Statistics

Obituary

Book Reviews

The Rebellious Role of Peasants in European History

*Economist, Political Activist, Writer, bobmckee99@yahoo.com

https://doi.org/10.25003/RAS.15.01.0009

| Dees, Robert (2023), The Power of Peasants: Economics and Politics of Farming in Medieval Germany, vol. 1 and 2, first edition, Commons Press, pp. 1794. |

|

The Power of Peasants: Economics and Politics of Farming in Medieval Germany by Robert Dees is an opus of over 1,700 pages in two volumes. In contrast to mainstream economic historians, Dees argues that peasants in overwhelmingly agricultural ancient and medieval economies played an essential role in advancing civilisation in Europe. By “civilisation,” in this context, I mean raising the productivity of labour through improvements in farming technique and technical innovations – the “creative genius” of farmers – and thus the living standards and the health of the multitude. Peasants were not some amorphous dull mass that were mere victims of the class rule of Roman slaveholders or feudal lords. They had agency; they fought on many occasions (though not often successfully) to break the grip of the ruling class. When they succeeded and gained a degree of independence in production and control of the surplus produced, they took society forward.

When peasants were suppressed in the Roman empire and the ruling class replaced them with slaves, the Roman empire went into economic crisis and eventually collapsed. When peasants were subjected to the penuries of serfdom under the rule of petty feudal regimes, the feudal order eventually fell into a series of plague-ridden crises and perpetual wars that sucked out any progress.

The main focus of the book is on the economics and politics of farming in south Germany from 1450 to 1650. Dees starts, however, with the role of peasants in building the Roman republic and driving its successful expansion. It was when the ruling orders replaced free farmers with slaves from conquests in war, forcing the peasantry into debt and expropriating peasant land to create huge estates, that Roman society went into crises that led to class battles, civil wars, the end of the republic, and eventually to internal collapse and external invasion by the peasant “barbarians” of the north. These peasant “barbarians” from northern Europe had developed farming that produced “more food, more farmers, more warriors, until they overran the empire.”

Dees disputes the common mainstream revision that Rome did not collapse, but instead morphed into “late antiquity” and then slowly evolved into a feudal system. In his view, with which I agree, the Roman slave economy did collapse and productivity, technology, and culture declined. As Dees writes, in 900 A. D., more than 400 years after the end of the Western Roman empire, “there was not a single city in England and few in northern Europe.”

It was around this period that a revival in productivity and innovation occurred, powered by peasant farmers now freed from Roman slavery. Although a new feudal class formed in the early medieval period, it was still too weak and disparate to suppress the peasantry. Gradually, feudal lords exerted more control than before. As a result, agriculture began to stagnate and Europe descended into internal warfare. Feudal lords launched “Crusades” against Muslims in Palestine and pogroms against Jewish people at home to consolidate their control. As poverty rose and health and nutrition fell, disease (the “Black Death,” for example) became the norm and feudal rulers engaged in what became the Hundred Years’ War of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. Although peasant revolts erupted, they were crushed.

The plague and the continual wars, in particular, the Wars of the Roses in England in the mid-fifteenth century, so weakened the feudal class that the peasantry regained some independence over their production. Eventually, in combination with the artisans, shopkeepers, and merchants of the towns, they were able to escape from feudal penury. The republics of the Netherlands and England emerged and opened the door for a new mode of production based on capitalism, made possible by the revival of the productive use of the agricultural surplus.

Agricultural and commercial progress was possible in England and the Netherlands. In Germany, where Dees concentrates his analysis, that did not happen. Petty feudal regimes triumphed over the peasants in a series of class wars (such as the Peasants’ War of 1524–25). As a result, rents and debt spiralled and farmers could do nothing to raise productivity. Germany stagnated in a feudal quagmire. The Thirty Years’ War of 1616–48 was the culmination of feudal stagnation and collapse.

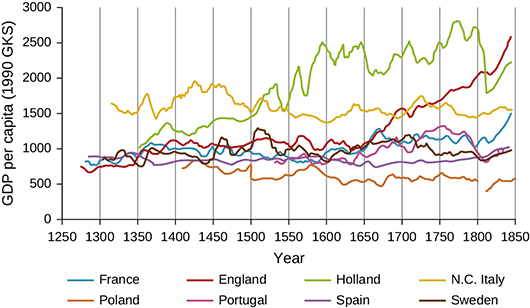

Differences in gross domestic product (GDP) per capita can be seen in Figure 1 below. The Renaissance Italian city-states were the leaders in per capita GDP in Europe up to the mid-fifteenth century. The Netherlands began to catch up and lead from the 1550s. England began to close the gap after the Civil War of the 1640s destroyed feudalism and eventually overtook Holland through industrialisation from the late eighteenth century onwards. In the meantime, continental Europe stagnated, with only France taking off after the Revolution in the late eighteenth century freed the peasantry from feudalism.

Figure 1 GDP per capita by country, 1250–1850 in GK$

Of France, Marx (1907) wrote in the 18th Brumaire:

After the first Revolution had transformed the semi-feudal peasants into freeholders, Napoleon confirmed and regulated the conditions in which they could exploit undisturbed the soil of France which they had only just acquired, and could slake their youthful passion for property . . .

Under Napoleon the fragmentation of the land in the countryside supplemented free competition and the beginning of big industry in the towns. The peasant class was the ubiquitous protest against the recently overthrown landed aristocracy. The roots that small-holding property struck in French soil deprived feudalism of all nourishment. The landmarks of this property formed the natural fortification of the bourgeoisie against any surprise attack by its old overlords.

Dees does a demolition job on the population theory of the reactionary nineteenth century English parson, Thomas Malthus, who argued that stagnation in production was the product of overpopulation, and that Europe could not support “too many people.” This dogma has been refuted by many since. Dees cites Walter Blith, yeoman farmer and captain in Cromwell’s parliamentary army during the English Civil War, who said that “any land by cost and charge may be made rich and rich as land can be.” In refuting Malthus, Dees also cites Engels (as I did in my book Engels 200 (2020): “the productive power at humanity’s disposal is immeasurable. The productivity of the soil can be increased infinitely by the application of capital, labour and science.” As Dees writes,

the Netherlands has a population density more than eleven times that of the Congo. According to the “Malthus fraud,” the people of the Netherlands must be starving and those of the Congo prospering.

Engels remarked that if Malthus wanted to be consistent, he must “admit that the earth was already overpopulated when only one man existed.”

The Malthusian argument continues to find its way into mainstream economics to this day, even though the main theme now is that the world produces too much and people consume too much and so are destroying nature and the planet. Dees argues that it was because of feudalism and class rule that people were poor and starving and subject to plagues, not because there were too many people. Now the argument should be that nature and the planet are being destroyed by capitalism and the rule of rich oligarchs, not because of too much production.

Dees offers the reader a materialist conception of history in his account of the role of the peasantry in Europe since ancient Rome. Rome’s rise was powered by free farmers; its decline and collapse was caused by the suppression of those farmers by a slaveholding aristocracy and emperors. Northern Europe freed itself from Roman rule and peasant farming was able to expand production and feed more people. However, a feudal aristocracy based on armed might was eventually able to subject most of the peasants into serfdom and to live off their labour, thus ending agricultural progress. Only when feudalism collapsed through wars and plagues did Northern Europe’s revolutions allow the peasantry to revive innovative farming.

In Germany, feudalism was sustained, thus delaying the emergence of capitalist agriculture and commerce well into the nineteenth century. Dees provides a new explanation for the causes of the Peasants’ War of 1525 and the long-term effects of its defeat. This will be of particular interest in this 500th anniversary year of that event.