ARCHIVE

Vol. 13, No. 1

JANUARY-JUNE, 2023

Editorial

Research Articles

Research Notes and Statistics

Interviews

Book Reviews

Referees

What is the Contribution of Government Support to Farm Incomes?

A Case Study of Rice Cultivation from Kerala, India

*Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) Postdoctoral Fellow, Institute of Economic Research, Hitotsubashi University, Tokyo, deepakjohnson91@gmail.com.

https://doi.org/10.25003/RAS.13.01.0004

Abstract: Average income per hectare from rice cultivation in Kerala is the third highest in India, with only the green-revolution States of Haryana and Punjab reporting higher incomes. This paper seeks to examine the role of government support in observed farm incomes in Kerala. As secondary data sources do not allow for such disaggregation, I use primary data from a sample survey of rice-cultivating households in a high-productivity region of central Kerala. The analysis shows that rice cultivators benefited from multiple forms of support provided by the central government, the State government, and the local government. Price support by the State government was crucial in realising the current levels of income in Kerala.

Keywords: Rice Cultivation, Agricultural Policy, Farm Incomes, Price Support, Kerala, India

Introduction

This paper examines the impact of policy on incomes of rice cultivators in the State of Kerala in India. Three issues are explored. First, how do incomes from rice cultivation in Kerala compare to incomes in other regions? Secondly, what are the components of farm incomes from rice production? Specifically, what is the contribution of State and local government support to incomes from rice cultivation? Thirdly, do these benefits of State support vary across farms? To answer these questions, I estimate specific components of farm incomes for rice cultivators in the Kole wetland region of Kerala, an area of high productivity. While previous studies (such as GoK 1999; Harilal and Eswaran 2017; and Narayanan 2003) have acknowledged the role of government support in farm-level incomes, this is the first attempt to provide a detailed accounting of the contribution of State and local government interventions to incomes from rice production in Kerala.

Motivation for the Study

Kerala, located in the south-western part of India and home to around 35 million people, has been known in the literature for its unique development experience (Centre for Development Studies 1975; Franke and Chasin 1992; Parayil 2000; and V. K. Ramachandran 1997). In recent years, public discussion and policy have emphasised issues of production and income growth (GoK 2017, 2023). In particular, the steady decline in the production of rice and the area under rice cultivation, which has declined from around 900,000 hectares in 1975-76 to 200,000 hectares in 2016-17 (Johnson 2018), has been of concern.

The conservation of rice cultivation in Kerala has become an important concern of the State Government for various reasons. First, Kerala has several rice agro-ecosystems that are unique in “topography, soil, and abiotic factors, variations in resource endowments and seasonal differences” (GoK 1999; Kumari 2011; and Sasidharan 2019).1 For example, in the Kuttanad rice agro-ecosystem, which is part of the larger Vembanad-Kol Ramsar site, rice is cultivated in below sea-level polders and is recognised as a Globally Important Agricultural Heritage System (GIAHS) by the Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO). Secondly, while only 14 per cent of the total foodgrain requirement of Kerala is met by own production (Rajasekharan and Anila 2019), there is a diversity of landraces in Kerala, including short-, medium-, long-duration, and medicinal and aromatic rice varieties. Kerala is known for the cultivation of highly nutritive red-rice varieties (known as matta rice). The most widely cultivated rice varieties in Kerala, such as Jyothi and Uma, are modern matta varieties developed with local rice varieties as pedigree. Thirdly, Kerala falls in a region of India that is particularly suited to lowland rice cultivation with respect to factors such as water availability, temperature, and soil characteristics (Pathak et al. 2020). The region thus has potential for further rice cultivation.

Successive State Governments after the 1990s have used direct and indirect measures to arrest the decline in area under rice cultivation. One of the reasons for a large-scale shift of land away from rice cultivation has been low profitability (GoK 1999; Harilal and Eswaran 2017; Kannan and Pushpangadan 1988, 1990; Karunakaran 2014; Narayana 1992; and Narayanan 2003). To encourage cultivation, governments have attempted to increase profitability of rice farming in Kerala (GoK 1999; Thomas 2011), The Government of India announced a Minimum Support Price (MSP) for rice, and the Government of Kerala has provided a further incentive (termed “State Incentive Bonus”) to rice cultivators for around two decades. In addition, local self-governments have attempted to encourage rice cultivation through various means, such as providing subsidies, promoting group farming through self-help groups through the Kudumbashree scheme, and improving access to mechanisation (for more on these, see Krishnankutty et al. 2021; Praveen and Suresh 2015; M. T. Ramachandran and Das 2020; and Rashtriya Krishi Vikas Yojana n.d.).

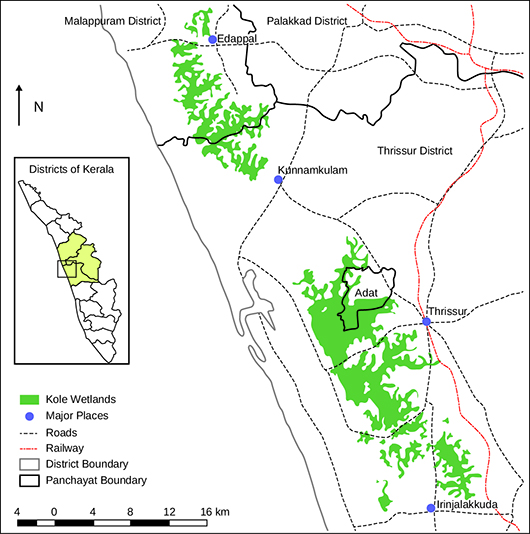

The primary data here are from a unique rice-based agro-ecosystem, the Kole wetland region in central Kerala, where specialised red rice (matta) varieties are grown and where yields are higher than the State average (for a description of the Kole rice cultivation ecosystem, see Johnson 2017). Although the Kole wetland region has also seen a decline in area under rice cultivation (Devi et al. 2017; Jeena 2011), this reduction in area is less than the loss of area under rice cultivation in neighbouring regions and for the whole State.2 However, even within the Kole wetland region, increased real-estate activity and the growing demand for residential land exerts pressure on rice cultivation (Raj and Azeez 2009).

This is also a region with a distinctive form of organisation of rice cultivation. Rice farming is undertaken by joint-farming societies (padasekharam) formed by farmers cultivating contiguous fields. Such arrangements exist in other parts of Kerala as well, but they are crucial to rice cultivation in the Kole wetland region. The joint-farming societies undertake key operations of water management in rice cultivation in the Kole wetland region. The societies elect their leadership, and the elected representatives deal with banks, local governments, and procurement agencies to, among other things, obtain low-interest loans, undertake agricultural operations, facilitate procurement, and help individual farmers to gain access to subsidies. On account of present levels of productivity and favourable institutional factors, rice cultivation is likely to continue in the Kole wetland region.

Although the area under rice cultivation has declined in Kerala, a farmer’s business income from rice was the third highest in Kerala among the States of India in 2018-19 (CCPC 2021). Only Punjab and Haryana had higher incomes. These were early green-revolution States, benefiting from the new high yielding variety (HYV) seeds, widespread mechanisation, and institutional support with respect to procurement and investment in irrigation (Bhalla and Singh 2012; Frankel 1971). Kerala lagged behind in terms of mechanisation, productivity, and incomes from rice cultivation for much of the green revolution period (Bhalla and Singh 2012).

In this context, the relatively high income per hectare from rice production is surprising, and I show that this is largely on account of State intervention in agriculture. On account of the absence of data, there has been no previous study of the actual extent of State support per hectare or per cultivator. Information on costs and incomes from crop production in India from the Comprehensive Scheme on Costs of Cultivation/Production of Principal Crops in India (CCPC Scheme) is not enough to allow us to ascertain the contribution of price and other forms of institutional support to crop incomes. The primary data in this paper, collected by means of a field survey, fill this gap for the study region.

Data and Methods

Study Area and Sample Characteristics

I use data on farm incomes and costs of cultivation from a survey of 65 agricultural households in Adat Village Panchayat in the Kole wetland region of Thrissur district that I conducted in 2018-19. Adat Village Panchayat (Figure 1) is one of the largest panchayats in the Kole wetland region. It has a large number of joint-farming societies within its geographical limits.3 The households were selected using simple random sampling without replacement from the lists of member-farmers provided by the joint-farming societies operating within the village panchayat. A single crop of rice was raised in Adat in 2018-19, and was grown from October-November 2018 to March-April 2019.4

Figure 1 Map of the Kole wetland region with Adat village panchayat

Among households in the sample, the average size of ownership holding of land was 1 hectare and the average size of operational holding of land was 1.31 hectares. Nineteen households in the sample leased land in; of the total extent of operational holdings 24 per cent was leased in. One household was a pure tenant household. The sample covered 8 households from the Scheduled Castes, 23 households from Other Backward Classes (OBC), and 34 households from other social groups (including caste Hindu and Christian households).

Most households (38 out of 65) in the sample operated marginal holdings (less than 1 hectare). The size of holding operated by individual households ranged from 0.1 to 6.9 hectares. The average size of land holding operated by Scheduled Castes (0.63 hectares) and Other Backward Class households (1 hectare) was lower than the average size of land holding operated by other households (1.69 hectares).

Methodology of Calculating Crop Incomes

The key variable of interest is net income from rice production. To estimate costs, I use concepts used by the Comprehensive Scheme for Calculation of Costs of Cultivation/Production for Principal Crops in India (CCPC Scheme).5 For calculating specific cost components, I have used the modifications made by the Foundation for Agrarian Studies (FAS) (FAS 2015).6

The main cost measure used is Cost A2, which stands for paid-out costs incurred by the producer (Appendix Table 1). Cost A2 is subtracted from the Gross Value of Output (GVO) to obtain net income from cultivation.7 To this, I add direct income transfers received by a household on account of rice cultivation to obtain rice income (RI). The final equation for rice income (RI) is:

Households receive different forms of government support: premium price for the output that increases the GVO, subsidies that reduce costs, and transfer incomes. The aggregate amount of support is calculated using equation (2) which is the difference between actual rice income and rice income in the absence of support measures provided by the State and local governments.

In equation (2), S stands for support; pr is the price of rough rice, pr* is price of rice in the absence of support, xr is the quantity of rough rice produced, pj is the actual price of inputs, pj* is the price without subsidy for inputs, and qj* is the quantity of inputs for which households received support.8 There were two inputs for which households received subsidy: lime and seed. Y* stands for direct income transfers from the State and local governments received by farm households.

The survey collected information on costs and incomes from all land parcels cultivated by the sample households, including those parcels located outside Adat Village Panchayat limits. I verified the information provided by households with officials in Adat Village Panchayat. Since I could not undertake a similar exercise for land parcels falling in other Village Panchayats, I restrict the analysis of accounting for support to land parcels located within Adat Village Panchayat and those with detailed data on costs and incomes (n=102).

It must be noted that the calculation of government support here is static in nature. The farm households may change their input use, responding to changes in reference prices, but this scenario is not considered.

Results

Levels of Income From Rice Cultivation

CCPC estimates show that net incomes per hectare were highest in Punjab and Haryana (over Rs 80,000 per hectare in 2018-19). As per CCPC, costs were highest in Kerala, and net income was Rs 66,771 per hectare. Kerala thus came third in terms of average income and profitability.

My estimates of costs and incomes in Adat Village and CCPC estimates for the top four rice-producing States of India (West Bengal, Uttar Pradesh, Andhra Pradesh, and Punjab) as well as for Haryana, Tamil Nadu, and Kerala for 2018-19 are shown in Table 1 (Appendix Table 2 provides statistics for rice production in the selected States). For Adat Village Panchayat, a modified estimate that excludes marketing costs, consistent with the practice adopted by the CCPC Scheme in Kerala, is also reported.9

Table 1 Average paid-out costs, incomes, and profitability of rice cultivation, various States and Adat, 2018-19 in Rs per hectare

| Sl. no. | Region | Cost A2 | Net Income | Profitability (per cent) |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5 = 4/3) |

| Estimates from the CCPC Scheme | ||||

| 1 | Andhra Pradesh | 55,128 | 51,442 | 93 |

| 2 | Haryana | 38,199 | 88,180 | 231 |

| 3 | Kerala | 66,635 | 66,771 | 100 |

| 4 | Punjab | 42,076 | 82,061 | 195 |

| 5 | Tamil Nadu | 51,803 | 30,697 | 59 |

| 6 | Uttar Pradesh | 34,198 | 26,678 | 78 |

| 7 | West Bengal | 39,491 | 28,698 | 73 |

| Estimates from the Survey of 2018-19 | ||||

| 8 | Adat | 85,081 | 79,986 | 94 |

| 9 | Adat (modified) | 74,351 | 91,365 | 123 |

Note: Adat uses all 102 owned and leased land parcels. Adat (modified) uses the same method followed by the CCPC Scheme for Kerala, i.e. excluding marketing costs and considering costs and incomes only for 84 owned land parcels (out of 102).

Source: Author’s calculations from the CCPC Scheme and Survey 2018-19.

The modified estimate for Adat shows that costs were higher than the Kerala average, but net incomes and profitability were higher too. As noted earlier, Adat belongs to a high-productivity rice-growing region of Kerala and this can explain the net income being higher than the State average. What is surprising is that net incomes in Adat were higher than the Punjab average, even though costs were almost twice the costs borne by cultivators in Punjab.10 I argue that government support plays a key role in boosting net incomes of cultivators in Adat village.

Forms of Government Support

Households received support from three levels of government: the Government of India, the Government of Kerala, and Adat village panchayat or local government (Table 2). Support provided by Adat panchayat originates independently of the State and Central Governments. These items of support are specific to local government institutions and are not available to farmers in other areas within the State.11

Table 2 Items of government support for rice cultivation and coverage of households and area operated, Adat village panchayat, 2018-19

| Sl. No. | Item of support | Amount, unit, and conditions | Number of households | Area (ha) |

| Government of India (Central Government) | ||||

| 1 | Minimum Support Price (MSP) | Rs 17.5 per kg | 64 | 63 |

| 2 | Cash transfer under Rashtriya Krishi Vikas Yojana (RKVY) | Rs 3000 per ha | 64 | 53 |

| 3 | Cash transfer under Paramparagat Krishi Vikas Yojana (PKVY) | Rs 1000 per farmer (only for households engaged in organic farming) | 6 | 6 |

| Government of Kerala (State Government) | ||||

| 4 | State Incentive Bonus (SIB) | Rs 7.8 per kg | 64 | 63 |

| 5 | Subsidy for lime | Rs 9 per kg (up to 600 kg lime per hectare for a land parcel) | 60 | 62 |

| 6 | Production incentive for rice farmers under two different schemes | Rs 2000 per ha | 64 | 53 |

| Adat Village Panchayat (local government) | ||||

| 7 | Subsidy for seed | Rs 31 per kg (up to 32 kg seeds per acre for a land parcel) | 63 | 64 |

| 8 | Incentive for organic farming | Rs 6000 per farmer | 6 | 6 |

| All households | 65 | 70 | ||

Notes: 1. The total number of land parcels considered here are 108 (and not 102 land parcels, as in other parts of this article). The six additional land parcels were managed jointly, and cost details were not available for them.

2. Rashtriya Krishi Vikas Yojana (RKVY) is a centrally sponsored scheme (CSS) in which 60 per cent of the funds are provided by Government of India and the remaining 40 per cent by the State Government. Since this originated as a Government of India measure, it is considered as part of the support offered by Government of India.

3. The production incentive provided by Government of Kerala consists of two schemes that each provided Rs 1000 per hectare to each farmer in 2018-19. One scheme covered rice farmers across the State and the other was specifically for rice cultivators in high-productivity areas such as the Kole wetland region.

Source: Information on public support obtained from Agriculture Office, Adat and Survey data 2018-19.

There were three types of government support: incentive payments involving land use, subsidies on inputs, and support prices for output.

All households received at least one form of government support for rice cultivation. The receipt of different items of support was conditional on tenurial status, marketing agency, and land area operated by a farmer in official records.12 Price support for rice was available to those who marketed to the government agency and price support for inputs was available to those who bought inputs from the input centre associated with the local cooperative bank. Most farmers sold their rice to the government agency and bought seed, fertilizers, and lime from the input centre managed by the cooperative bank. As a result of this, the number of households that received government support for any specific scheme ranged from 60 to 64.

There were two additional forms of support provided to cultivators who grew organic rice. A thousand rupees per farmer was provided as part of Paramparagat Krishi Vikas Yojana (PKVY) by the Government of India and an incentive for organic farming was provided by Adat Village Panchayat. Of 65 households, only six households were eligible and received incentives for organic farming.

The Central-level support offered by the Government of India and potentially covering all farmers in India was via the mechanism of the Minimum Support Price (MSP) and cash transfers. The Government of Kerala and Adat Village Panchayat provided cash transfers and input subsidies. The State government provided an additional price incentive.

A fourth form of support available to rice growers in Adat was on account of the institutional arrangement of padasekharam (joint-farming societies). All rice-cultivating households in Adat Village Panchayat were part of a joint-farming society, and all sample households benefited from their activities. While not easily quantified, the activities of joint-farming societies affected costs incurred by individual farmer households. Several operations require cooperative efforts and would have been difficult for individual farmers to undertake. The expenses for these operations were met through common income-earning activities of padasekharam such as farming coconut on outer bunds of fields, fish farming, and penning ducks on fields. Any surplus from these operations was shared with members or carried forward to subsequent years. If costs were higher than revenues, the loss was shared between constituent farmers as a membership contribution.

Contribution of Government Support to Rice Incomes

The items of support enumerated in Table 2 capture the major forms of support received by rice-cultivating households in the sample.13 To assess the contribution of the State and local governments, we first estimate incomes with only support from the Government of India.

Table 3 must be read as follows. The average Gross Value of Output (Column 3) for the sample was Rs 165,067 per hectare. If the Gross Value of Output is calculated with only the MSP offered by the Central Government (Column 4), then estimated GVO is lower, at Rs 115,161 per hectare. The difference between the two (Column 5) shows that measures of support provided by the Government of Kerala and the local government amounted to Rs 49,906 per hectare or 30 per cent of realised Gross Value of Output (Column 6). Input subsidies provided by the State and local governments amounted to six per cent of paid-out costs. And, of rice incomes, all forms of State and local government support amounted to 67 per cent or two-thirds of actual income.

Table 3 Gross Value of Output, costs and net incomes, and different forms of government support, Adat, 2018-19 in Rs per hectare and per cent

| Sl. No. | Measure | Realised value | Only GoI support | State + local support | Share of State + local support in realised value |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5 )= (3 – 4) | (6) = (5)/(3) |

| 1 | Gross Value of Output | 165,067 | 115,161 | 49,906 | 30 |

| 2 | Paid-out costs | 85,081 | 90,011 | 4,930 | 6 |

| 3 | Net income before transfer (1-2) | 79,986 | 25,150 | 54,836 | 69 |

| 4 | Direct transfer | 3,713 | 2,220 | 1,493 | 40 |

| 5 | Rice income (3+4) | 83,699 | 27,370 | 56,329 | 67 |

Note: Rice income is calculated for each land parcel.

Source: Survey data 2018-19.

Of the components of State and local government support, the most crucial forms are the price support or State Incentive Bonus (SIB) declared by the Government of Kerala. In 2018-19, the procurement price was Rs 25.3 per kg of rough rice in Adat (the component parts being an MSP of Rs 17.5 and SIB of Rs 7.8). Other measures, including input subsidies on seed and lime and direct income transfers from State and local governments accounted for 11 per cent of total support by State and local governments.

Variations Across Land Parcels

While the average level of rice income for Kerala is high, earlier research has shown that cultivators on leased land and those with smaller parcels received lower incomes than cultivators on own land and with larger parcels. (Harilal and Eswaran 2017; Jeena 2011; and Nair and Menon 2006). Studies in neighbouring Tamil Nadu have found that Scheduled Castes received lower average crop incomes than farmers from other social groups (Surjit 2014). In this section, I examine variations in observed rice incomes and support received for different groups of cultivators.

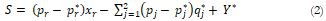

Figure 2 is a histogram for rice income, State and local government support, and rice income without support. There is sizeable variation in rice income per hectare across land parcels, ranging from (-) Rs 14,749 to Rs 173,236. Values for State and local government support per hectare were bunched together, with more than one-half of observations around the mean (Rs 56,329). When State and local government support are excluded, the number of land parcels with negative rice incomes was 22 (as compared to two in the top histogram).

Figure 2 Histogram of rice income, State and local support, and rice income without support, 2018-19

Note: X-axis is in Rs per hectare.

Appendix Table 3 provides a comparison of incomes and farm support across different socio-economic groups. There are three specific findings. First, while there is no statistically significant variation in rice incomes as between land parcels operated by Scheduled Castes and Other Backward Class households and households from other social groups, the difference is large though not statistically significant when State and local government support are excluded. Secondly, as expected, there is a statistically significant difference between income on leased and owned land parcels. The rice income per hectare from parcels of leased land was lower than from parcels of owned land, because of the rent paid on leased-in land. On leased-in plots, the average rice income per hectare would be negative without State and local support. Thirdly, the difference in rice incomes per hectare as between marginal (n=81) and other (n=21) land parcels was not statistically significant. The marginal land parcels had an average area of 0.4 hectares and other land parcels had an average area of 1.6 hectares in Adat.

In brief, my finding is that there was no statistically significant difference in net incomes per hectare of households belonging to different castes and operating different sizes of land holding. This in turn implies that neither State and local government support per hectare nor yields varied very much across types of cultivator households.14

Implications and Conclusion

My study shows that the implementation of a public price support and procurement policy enhanced incomes obtained by rice cultivators in Adat Village Panchayat. For argument’s sake, I provided a comparison of incomes from rice cultivation in Adat and Punjab (Table 1). The average yield in Adat (6.4 tonnes per hectare) was lower than the average yield in Punjab (6.8 tonnes per hectare). Average cost in Adat was double average cost in Punjab, with farmers in Adat incurring higher costs per hectare for almost all components of costs of cultivation. Among the major components of costs, substantial differences were seen with respect to labour use and fertilizer use in the two regions. Hired human labour accounted for 25 per cent of average costs in Punjab and 30 per cent in Adat. Fertilizer and manure costs were nine per cent of average costs in Punjab and 21 per cent in Adat. But, even with lower yields and higher costs, farmers in Adat received higher incomes than in Punjab.

I argue that the price realised by farmers in Adat explains this scenario. The average price in Adat was Rs 25.5 per kg, whereas it was Rs 18.3 per kg of paddy in Punjab. The average price in Punjab was closer to the MSP (Rs 17.5 per kg of paddy). The price received in Adat, as in other parts of Kerala, included the State Incentive Bonus (SIB). Further, all but a few farmers sold their produce to government procurement agencies in 2018-19. Within my sample, the output of only one land parcel was sold to a private agent, as it was an organic crop and obtained a premium price.

The public procurement undertaken in Adat is part of the foodgrain procurement and public distribution system formally instituted by the Government of India in the mid-1960s to ensure remunerative prices for farmers and food security (Venkateswarlu 2021). The MSP, set by the Government of India, is the price offered for procurement operations across the country. It is based on a weighted average of costs across States. Although there are many problems associated with the calculation of MSP (see Kamra and Ramakumar 2019; Narayanamoorthy 2017; Sarkar, V. K. Ramachandran, and Swaminathan 2014; Sen and Bhatia 2004; and Surjit 2017), the current weighting method for the Minimum Support Price (MSP) reflects conditions prevalent in large rice-producing States such as Punjab.

At existing yield levels, MSP for 2018–19 was 2.8 times the cost of cultivation in Punjab, 1.4 times the cost in Kerala as a whole, and 1.5 times the cost in Adat. The SIB instituted by the Government of Kerala improved this ratio substantially. The price received by farmers inclusive of SIB and MSP, was 2.1 times the average cost of cultivation for Kerala as a whole, and 2.2 times the average cost of cultivation in Adat.

Price support was available to most rice-growing households in Kerala.15 The estimates for 2018-19 suggest that while 14 and 18 per cent of agricultural households cultivating rice sold their output to procurement agencies across India in the kharif and rabi seasons, the figures were 64 and 75 per cent in Kerala (GoI 2021). The high coverage of public procurement and the provision of support measures in Adat are thus not surprising. The joint-farming societies and other government agencies were active during the procurement period in assisting farmers to market their produce.

The foregoing discussion also raises questions of the long-term fiscal sustainability of such the support measures now in place. While it may be possible to support rice farmers by way of price support at present in Kerala, non-price methods will have to be explored in the long run. Without the State Incentive Bonus (SIB) and at the existing level of costs, a rough calculation shows that the average yield will have to be 45 per cent more than the current level to maintain the same level of income. Raising yields is thus the longer run option to maintain high incomes. This in turn requires investment in research and extension services.

The question of the extent of price support received by farm households is an important one in the Indian policy debate. Over the last decade, crop incomes have fallen in real terms, as indicated by a growth rate of -1.29 per cent from 2012-13 to 2018-19 (Narayanamoorthy and Sujitha 2021). The costs of production have increased, particularly after the 1990s, on account of low yield growth, and increased input prices (Dev and Rao 2010; Raghavan 2008; and Srivastava, Chand, and Singh 2017). The relationship between price support and farmers’ income was central to the recent farmers’ protests in India (Jodhka 2021; Krishnamurthy 2021; Lerche 2021; RAS 2020; and Singh and Bhogal 2021).

In these discussions, sufficient attention has not been paid to the actual quantitative contribution of price support and other support measures to farmers’ incomes at the household and farm level (Birthal 2019; Chand 2017; Gulati, Ferroni, and Zhou 2018; and Gulati, Kapur, and Bouton 2020). Nor has there been much discussion of institutional arrangements for income enhancement, such as padasekharams or Kudumbashree groups in Kerala that have brought fallow land under cultivation.

Some conclusions emerge from our study that are relevant to the wider policy debate touched upon above.

First, the presence of State and local-level initiatives in terms of agricultural marketing and price policies can make a big difference to the profitability of crop production. Secondly, such measures seem justified in Kerala where costs are relatively high but cultivation of rice is valued for ecological, nutritive, and cultural reasons. Thirdly, income transfers via price support constitute the largest and most widely prevalent component of government support to farmer incomes. Any measure that tries to replace price support may fail to incentivise farmers if the gains are not proportionate to the gains that can be achieved under a price support mechanism. Lastly, moving away from price-based measures will require major investments in yield-enhancing non-price measures of support.

Acknowledgements: I thank Madhura Swaminathan and two anonymous referees for their comments on this paper.

Notes

1 The precise number of rice agro-ecosystems varies from seven to nine due to different methods of classification. The most common type of classification is as follows (1) Midland and Malayoram, (2) Palakkad plains and Chittoor black soil, (3) Kuttanad (Kuttanad and the Kole wetland regions), (4) Pokkali (comprising pokkali and kaipad rice-cultivating lands), (5) Onattukara, (6) High Ranges, and (7) Coastal plains.

2 From a dataset on land use and cropping pattern, I estimate that the gross cropped area under rice fell from 48 per cent of total cropped area in 1981-82 to 14 per cent in 2007-08 and 13 per cent in 2013-14. The gross cropped area under rice was 39 per cent of the total area of Thrissur district in 1981-82 to eight per cent in 2007-08 and seven per cent in 2013-14.

3 According to administrative data from 2013, Adat Village Panchayat has 13 joint-farming societies (this is the highest number among panchayats in the Kole region; four other village panchayats have the same number) and is second in terms of area and the number of farmers in the panchayat. There are 34 village panchayats in the Kole wetland region.

5 The manual of CCPC Scheme (GoI 2008) provides the detailed definition of concepts and methodology used by my surveys.

6 This method corresponds to the budget analysis in Timmer, Falcon, and Pearson (1983).

7 This is usually referred to as farm business income in the literature to distinguish it from other concepts of crop incomes (Dev and Rao 2010). I use net income and farm business incomes interchangeably in this paper.

8 There is no limit on the quantity of inputs that households can buy. However, subsidy is not provided for the entire quantity purchased by the household and is fixed according to norms decided by the subsidy-granting agency. There were such norms for agricultural lime and seed, the inputs under consideration. To illustrate, in case of seed, pj*for seed is Rs 41 per kg. The price paid by the farmer (pj) is Rs 10 per kg and the subsidy is Rs 31 per kg. The subsidy is available only for a limited quantity of seed, qj*, which, in this case, is 32 kg per acre. For seed purchased above this limit, the farmer has to pay Rs 41 per kg.

10 The quality of data collected in the primary survey is likely to be better than the quality of data in the CCPC reports.

12 In general, owners received funds in their bank accounts and benefits were not received by tenants.

13 Some support measures were not captured by the household survey, as they are difficult to be quantified. The electricity for irrigation in the Kole wetland region is provided free by government. Governments also bear a part of crop insurance premium, which are a subsidy to the cultivators. There are other infrastructure projects undertaken by various government agencies that support rice cultivators.

14 With respect to paid-out costs (Cost A2) per hectare, there was no statistically significant difference between land parcels in terms of social groups and size class of land parcels.

References

| Bhalla, G. S., and Singh, Gurmail (2012), Economic Liberalisation and Indian Agriculture: A District-Level Study, Sage Publications, New Delhi. | |

| Birthal, Prathap S. (2019), “From Food Security to Farmers’ Prosperity: Challenges, Prospects, and Way Forward,” Indian Journal of Agricultural Economics, vol. 74, no. 1, pp. 78–95. | |

| Centre for Development Studies (1975), Poverty, Unemployment, and Development Policy: A Case Study of Selected Issues with Reference to Kerala, United Nations Organization, New York. | |

| Chand, Ramesh (2017), “Doubling Farmers’ Income: Strategy and Prospects,” Indian Journal of Agricultural Economics, vol. 72, no. 1, pp. 1–23. | |

| Comprehensive Scheme on Cost of Cultivation/Production of Principal Crops in India (CCPC) (2021), Estimate of Cost of Cultivation/Production and Related Data, Directorate of Economics and Statistics, Ministry of Agriculture and Farmers’ Welfare, Government of India. | |

| Dev, S. Mahendra, and Rao, N. Chandrasekhara (2010), “Agricultural Price Policy, Farm Profitability and Food Security,” Economic and Political Weekly, vol. 45, no. 26/27, pp. 174–182. | |

| Devi, P. Indira, Sarada, A. P., Rajesh, K., and Jayasree, M. G. (2017), “Land-Use Changes Ecosystem Functions and Household Welfare,” in Water and Land Management for Food and Livelihood Security, Technical Papers of First Asian Conference on Water and Land Management for Food and Livelihood Security, Raipur. | |

| Foundation for Agrarian Studies (FAS) (2015), Calculation of Household Incomes: A Note on Methodology, available at https://fas.org.in/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/Calculation-of-Household-Incomes-A-Note-on-Methodology.pdf, viewed on July 13, 2023. | |

| Franke, Richard W., and Chasin, Barbara H. (1992), “Kerala State, India: Radical Reform as Development,” International Journal of Health Services, vol. 22, no. 1, pp. 139–156. | |

| Frankel, Francine R. (1971), India’s Green Revolution: Economic Gains and Political Costs, Princeton University Press, Princeton. | |

| Government of India (GoI) (2008), “Manual on Cost of Cultivation Surveys,” Central Statistical Office, Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation. | |

| Government of India (GoI) (2017), Fourteen Volume Report of the Committee on Doubling on Farmer’s Income, Committee on Doubling Farmers’ Income, Department of Agriculture, Cooperation and Farmers’ Welfare, Ministry of Agriculture & Farmers’ Welfare, available at https://agricoop.nic.in/en/Doubling, viewed on July 14, 2023. | |

| Government of India (GoI) (2021), “Situation Assessment of Agricultural Households and Land and Livestock Holdings of Households in Rural India, 2019,” NSS Report No. 587, National Statistical Office, Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation. | |

| Government of India (GoI) (n.d.), “Five Year Series data from 2016-17 to 2020-21,” Directorate of Economics and Statistics, Ministry of Agriculture and Farmers Welfare. | |

| Government of Kerala (GoK) (1999), Report of the Expert Committee on Paddy Cultivation in Kerala, Volume One, Main Report, Thiruvananthapuram. | |

| Government of Kerala (GoK), State Planning Board (2017), Approach Paper to the Thirteenth Five Year Plan, State Planning Board, Thiruvananthapuram. | |

| Government of Kerala (GoK), State Planning Board (2023), Approach Paper to the Fourteenth Five Year Plan, State Planning Board, Thiruvananthapuram. | |

| Gulati, Ashok, Ferroni, Marco, and Zhou, Yuan (eds.) (2018), Supporting Indian Farms the Smart Way, Academic Foundation and ICRIER, New Delhi. | |

| Gulati, Ashok, Kapur, Devesh, and Bouton, Marshall M. (2020), “Reforming Indian Agriculture,” Economic and Political Weekly, vol. 55, no. 11, pp. 35–42. | |

| Harilal, K. N., and Eswaran, K. K. (2017), “Agrarian Question and Democratic Decentralization in Kerala,” Agrarian South: Journal of Political Economy, vol. 5, no. 2-3, pp. 292–324. | |

| Jeena, T. S. (2011), “Agriculture-Wetland Interactions: A Case Study of the Kole Land Kerala,” RULNR Monograph no. 6, Research Unit for Livelihoods and Natural Resources, Centre for Economic and Social Studies, Hyderabad. | |

| Jodhka, Surinder S. (2021), “Why Are the Farmers of Punjab Protesting?”The Journal of Peasant Studies, vol. 48, no. 7, pp. 1356–1370. | |

| Johnson, Deepak (2017), “Rice Cultivation in Kole Wetlands of Kerala,” Blog-post, Dec 27, available at https://fas.org.in/rice-cultivation-in-kole-wetlands-of-kerala/, viewed on July 23, 2023. | |

| Johnson, Deepak (2018), “Cropping Pattern Changes in Kerala, 1956–57 to 2016–17,” Review of Agrarian Studies, vol. 8, no. 1, pp. 65–99. | |

| Kamra, Ashish, and Ramakumar, R. (2019), “Underestimation of Farm Costs: A Note on the Methodology of the CACP,” Review of Agrarian Studies, vol. 9, no. 1, pp. 112–126. | |

| Kannan, K. P., and Pushpangadan, K. (1988), “Agricultural Stagnation in Kerala: An Exploratory Analysis,” Economic and Political Weekly, vol. 23, no. 39, pp. A120–A128. | |

| Kannan, K. P., and Pushpangadan, K. (1990), “Dissecting Agricultural Stagnation in Kerala: An Analysis Across Crops, Seasons, and Regions,” Economic and Political Weekly, vol. 25, no. 25/26, pp. 1991–1993, 1995–97, 1999–2004. | |

| Karunakaran, N. (2014), “Determinants of Changes in Cropping Pattern in Kerala,” Journal of Rural Development, vol. 33, no. 4, pp. 367–376. | |

| Krishnamurthy, Mekhala (2021), “Agricultural Market Law, Regulation and Resistance: A Reflection on India’s New ‘Farm Laws’ and Farmers’ Protests,” The Journal of Peasant Studies, vol. 48, no. 7, pp. 1409–1418. | |

| Krishnankutty, Jayasree, Blakeney, Michael, Raju, Rajesh K., and Siddique, Kadambot H. M. (2021), “Sustainability of Traditional Rice Cultivation in Kerala, India — A Socio-Economic Analysis,” Sustainability, vol. 13, no. 2, available at https://doi.org/10.3390/su13020980, viewed on July 14, 2023. | |

| Kumari, S. Leena (2011), “Status Paper on Rice in Kerala,” Rice Knowledge Management Portal. | |

| Lerche, Jens (2021), “The Farm Laws Struggle 2020–2021: Class-Caste Alliances and Bypassed Agrarian Transition in Neoliberal India,” The Journal of Peasant Studies, vol. 48, no. 7, pp. 1380–1396. | |

| Nair, K. N., and Menon, Vineetha (2006), “Lease Farming in Kerala: Findings from Micro Level Studies,” Economic and Political Weekly, vol. 41, no. 26, pp. 2732–2738. | |

| Narayana, D. (1992), “Interaction of Price and Technology in the Presence of Structural Specificities: An Analysis of Crop Production in Kerala,” unpublished PhD thesis, Indian Statistical Institute, Kolkata. | |

| Narayanamoorthy, A. (2017), “Farm Income in India: Myths and Realities,” Indian Journal of Agricultural Economics, vol. 72, no. 1, pp. 49–75. | |

| Narayanamoorthy, A., and Sujitha, K. S. (2021), “Trends and Determinants of Farmer Households’ Income in India: A Comprehensive Analysis of SAS Data,” Indian Journal of Agricultural Economics, vol. 76, no. 4, pp. 620–642. | |

| Narayanan, N. C. (2003), Against the Grain: The Political Ecology of Land Use in a Kerala Region, India, Shaker Publishing, The Netherlands. | |

| Parayil, Govindan (ed.) (2000), Kerala: The Development Experience: Reflections on Sustainability and Replicability, Zed Books, New York. | |

| Pathak, H., Tripathi, R., Jambhulkar, N. N., Bisen, J. P., and Panda, B. B. (2020), “Eco-Regional Rice Farming for Enhancing Productivity, Profitability and Sustainability,” NRRI Research Bulletin no. 22, ICAR-National Rice Research Institute, Cuttack. | |

| Praveen, K. V., and Suresh, A. (2015), “Performance and Sustainability of Kudumbashree Neighbourhood Groups in Kerala: An Empirical Analysis,” Indian Journal of Agricultural Economics, vol. 70, no. 3, pp. 1–9. | |

| Raghavan, M. (2008) “Changing Pattern of Input Use and Cost of Cultivation,” Economic and Political Weekly, vol. 43, no. 26/27, pp. 123–129. | |

| Raj, P. P. Nikhil, and Azeez, P. A. (2009), “Real Estate and Agricultural Wetlands in Kerala,” Economic and Political Weekly, vol. 44, no. 5, pp. 63–66. | |

| Rajasekharan, P., and Anila, T. (2019), “Rice in Kerala: Towards an Evolutionary Perspective,” in Rajasekharan, P., and Sasidharan, N. K. (eds.), Rice in Kerala: Traditions, Technologies and Identities: A Life Perspective, State Agricultural Prices Board, Government of Kerala. | |

| Ramachandran, Madhav Tipu, and Das, Arindam (2020), “Collective Farming and Women’s Livelihoods: A Case Study of Kudumbashree Group Cultivation,” Canadian Journal of Development Studies, vol. 41, no. 4, pp. 525–543. | |

| Ramachandran, V. K. (1997), “On Kerala’s Development Achievements,” in Dreze, Jean, and Sen, Amartya (eds.), Indian Development, Oxford University Press, Oxford. | |

| Rashtriya Krishi Vikas Yojana (n.d.), “Kerala: Food Security Army,” available at https://rkvy.nic.in/static/download/RKVY_Sucess_Story/Kerala/Food_Security_Army.pdf, viewed on July 14, 2023. | |

| Review of Agrarian Studies (RAS) (2020), “On the Farmers’ Protests in India,” Review of Agrarian Studies, vol. 10, no. 2, pp. 4–6. | |

| Sarkar, Biplab, Ramachandran, V. K., and Swaminathan, Madhura (2014), “Aspects of the Political Economy of Crop Incomes in India,” World Review of Political Economy, vol. 5, no. 3, pp. 392–413. | |

| Sasidharan, N. K. (2019), “Special Rice Production Systems in Kerala,” in Rajasekharan, P., and Sasidharan, N. K. (eds.), Rice in Kerala: Traditions, Technologies and Identities: A Life Perspective, State Agricultural Prices Board, Government of Kerala. | |

| Sen, Abhijit, and Bhatia, M. S. (2004), Cost of Cultivation and Farm Income, Volume 14, State of the Indian Farmers: A Millennium Study, Department of Agriculture and Cooperation, Ministry of Agriculture, Government of India. | |

| Singh, Sukhpal, and Bhogal, Shruti (2021), “MSP in a Changing Agricultural Policy Environment,” Economic and Political Weekly, vol. 56, no. 3, pp. 12–15. | |

| Srivastava, S. K., Chand, Ramesh, and Singh, Jaspal (2017), “Changing Crop Production Cost in India: Input Prices, Substitution and Technological Effects,” Agricultural Economics Research Review, vol. 30, pp. 171–182. | |

| Surjit, V. (2014), “Tenancy and Distress in Thanjavur Region, Tamil Nadu: A Case Study of Palakurichi Village,” in Ramachandran, V. K., and Swaminathan, Madhura (eds.), Dalit Households in Village Economies, Tulika Books, New Delhi. | |

| Surjit, V. (2017), “The Evolution of Farm Income Statistics in India: A Review,” Review of Agrarian Studies, vol. 7, no. 2, pp. 39–61. | |

| Swaminathan, M. S. (2006), “Reports of the National Commission on Farmers,” Six Reports, Ministry of Agriculture, Government of India. | |

| Thomas, Jayan Jose (2011), “Paddy Cultivation in Kerala,” Review of Agrarian Studies, vol. 1, no. 2, pp. 215–226. | |

| Timmer, C. P., Falcon, W. P., and Pearson, S. R. (1983), Food Policy Analysis, The Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore and London. | |

| Venkateswarlu, Akina (2021), Political Economy of Agricultural Development in India, Aakar Books, New Delhi. |

Appendix

Appendix Table 1 Components of Cost A2

| Sl. No. | Component |

| 1 | Hired human labour |

| 2 | Owned and hired bullock labour |

| 3 | Owned and hired machinery |

| 4 | Farm-produced and purchased seeds |

| 5 | Insecticides and pesticides |

| 6 | Owned and purchased manure |

| 7 | Fertilizers |

| 8 | Depreciation of implements and machinery |

| 9 | Irrigation charges |

| 10 | Land revenue |

| 11 | Marketing costs |

| 12 | Miscellaneous expenses |

| 13 | Interest on working capital |

| 14 | Rent paid for leased-in land |

Source: FAS (2015); GoI (2008)

Appendix Table 2 Production of rice by selected States, 2018-19 in thousand tonnes and per cent

| State/Region | Production (000 tonnes) | Share in All-India Production (per cent) |

| Andhra Pradesh | 8,235 | 7.1 |

| Haryana | 4,516 | 3.9 |

| Kerala | 578 | 0.5 |

| Punjab | 12,822 | 11.0 |

| Tamil Nadu | 6,131 | 5.3 |

| Uttar Pradesh | 15,545 | 13.3 |

| West Bengal | 16,242 | 13.9 |

| All-India | 116,478 | 100.0 |

Source: GoI (n.d.)

Appendix Table 3 Tests of significance for difference in rice income across social groups, land size, and type of land lease, 2018-19 in Rs per hectare

| Sl. no. | Category | Rice income | State and local support | Rice income without support |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) |

| (3)-(4) | ||||

| Others vs. SC and OBC | ||||

| 1 | Others (n=55) | 90,017 | 56,227 | 33,790 |

| 2 | SC and OBC (n=47) | 76,305 | 56,447 | 19,858 |

| 3 | Mean difference | 13,712 | -220 | 13,932 |

| 4 | t-statistic | 1.6 | -0.1 | 1.8 |

| Leased vs. Owned | ||||

| 5 | Leased (n=18) | 38,897 | 53,820 | -14,923 |

| 6 | Owned (n=84) | 93,300 | 56,866 | 36,433 |

| 7 | Mean difference | -54,403 | -3,046 | -51,356 |

| 8 | t-statistic | -7.0 (***) | -1.4 | -7.3 (***) |

| Marginal vs. Others | ||||

| 9 | Marginal (n=81) | 82,244 | 57,110 | 25,134 |

| 10 | Others (n=21) | 89,312 | 53,313 | 35,998 |

| 11 | Mean difference | -7,068 | 3,797 | -10,864 |

| 12 | t-statistic | -0.7 | 1.2 | -1.1 |

Notes: Significance level in parenthesis for Welch Two Sample t-test: *** = significant at one per cent.

Source: Survey data 2018-19.

Date of submission of manuscript: March 30, 2023

Date of acceptance for publication: June 5, 2023