ARCHIVE

Vol. 3, No. 2

JULY, 2013-JANUARY, 2014

Research Articles

Research Notes and Statistics

Special Essay

Book Reviews

A New Statistical Domain in India:

An Enquiry into Gram Panchayat-Level Databases

Jun-ichi Okabe* with Aparajita Bakshi†

*College of Economics, Faculty of International Social Sciences, Yokohama National University, joka@ynu.ac.jp.

†Tata Institute of Social Sciences, Mumbai.

Abstract: This study deals with a new statistical domain, that of the village (or gram) panchayat. This domain has emerged in rural India as a consequence of the decentralisation programme initiated by the 73rd Amendment to the Indian Constitution. The work of the Expert Committee on Basic Statistics for Local-Level Development represents a landmark in this regard because it sheds light on the potential of village-level data sources for the new era of democratic decentralisation in India. This paper examines data sources at the gram panchayat level in relation to the needs that are generated if the Constitution (73rd Amendment) Act, 1992 is implemented comprehensively. From this point of view, the paper identifies three categories of data needs. These are: data required for self-governance, of which data required for managing the transition to full-scope constitutional devolution are a special component (Data Needs I and Ia); data required for matters of public finance (Data Needs II); and data required for micro-level planning (and plan implementation) for economic development and social justice (Data Needs III).

The paper proposes that an essential constituent of village-level data should be a list of individuals and families resident in the village (a “People’s List”). The accuracy and quality of the various people’s lists available with gram panchayats and other village-level agencies are examined here, using data from independent surveys conducted by the Foundation for Agrarian Studies in two villages.

Keywords: Democratic decentralisation, panchayati raj institutions, gram panchayat, rural statistical databases, Village Schedule, rural India, local self-government, rural governance.

Background to and Motivation for the Study1

A new statistical domain has emerged in rural India as a consequence of the Constitution (73rd Amendment) Act, 1992 – a domain based on the needs and constitutional functions of the gram panchayat (GP, or village panchayat). This paper deals with this new statistical domain. We discuss its potential and substance with respect to the village, which is at one end of the system of government, and the very first stage of collecting and recording data.

Panchayati raj institutions (PRIs) have become an integral part of rural life in India, and provide the institutional framework for the concept of democratic decentralisation.2 India’s Constitution (73rd Amendment) Act, 1992 (hereafter the 73rd Amendment) is indisputably a watershed in the history of democratic decentralisation. It gave constitutional status and devolved 29 functions to PRIs at the village, intermediate, and district levels, and also provided the mechanism for regular elections and raising financial resources, for panchayats to function as institutions of local self-government. Besides, it sought to ensure the empowerment of women and “the weaker sections of the population” through reservations. Since the panchayat is the tier of government closest to the citizens of the country and to the residents of its settlements, and thus in a better position than other tiers to appreciate their immediate concerns, the establishment of panchayats has paved the way for expanding the basic capabilities of rural residents.3 As a result of the 73rd Amendment of 1992, a large number of new leaders are presenting themselves on a local political stage in India.

The institutions of local self-government thus established require statistical databases for their own use. This requirement has necessitated systematic, from-below development of databases (National Statistical Commission 2001, para 9.2.17).

The provisions of the 73rd Amendment are such that panchayats need datasets to serve multiple and basic functions related to the self-governance of panchayats, micro-level planning of various development programmes and their implementation, and information on panchayat finances (Mukherjee 1994, p. 146).

In 2001, the National Statistical Commission under the chairmanship of C. Rangarajan (hereafter the Rangarajan Commission) argued that “even today no standardised system exists for the collection of local level databases in the country.”4 Under the system of centralised planning, there had been little demand for local-level databases.5 The Rangarajan Commission further noted that:

Quite a large amount of work has already been done in the past two decades by various working groups, study groups and committees constituted on the subject. However, implementation of these recommendations has not been taken seriously. (National Statistical Commission 2001, para 9.2.21)6

The statistical data sources available at the grass roots are primarily administrative records or census-type surveys.7 Large-scale sample surveys, which have been highly sophisticated in India, do not necessarily fulfil the data requirements at this local level since such surveys usually provide estimates at the national and State levels (ibid., para 9.2.22).8 The Rangarajan Commission aimed at stemming the deterioration in Indian administrative statistics at the farthest end of the government system.

Over the years, the Administrative Statistical System has been deteriorating and has now almost collapsed in certain sectors. The deterioration had taken place at its very roots namely, at the very first stage of collection and recording of data, and has been reported so far in four sectors: agriculture, labour, industry and commerce. The foundation on which the entire edifice of Administrative Statistical System was built appears to be crumbling, pulling down the whole system and paralysing a large part of the Indian Statistical System. This indisputably is the major problem facing the Indian Statistical System today. (Ibid., para 14.3.10)9

Accordingly, the Rangarajan Commission recommended that a committee of experts be constituted to look into all aspects related to the development of basic statistics for local-level development, and to suggest a minimum list of variables on which data needed to be collected at the local level (ibid., para 9.2.22). In keeping with this recommendation, the Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation (MoSPI) constituted, in December 2002, an Expert Committee under the chairmanship of S. P. Gupta, to review the existing system at local levels and recommend an appropriate system for regular collection of data on a set of core variables for local-level development. With the re-constitution of the Planning Commission in June 2004, Abhijit Sen became the chairman and completed the work of the Expert Committee, and submitted a comprehensive report on “Basic Statistics for Local Level Development” (hereafter BSLLD). The Committee reviewed the efforts made previously and provided a conceptual framework for developing a system of compilation of statistics, one originating from PRIs in the rural sector. Furthermore, the Committee developed Village Schedules and tested them through pilot studies. Subsequently (in 2009), the MoSPI launched a large-scale pilot scheme on BSLLD to identify data sources in 32 States and Union Territories of India (Government of India 2011).10

The essential recommendation made by this Expert Committee was expressed in its assertion that “the Gram Panchayat should consolidate, maintain and own village level data” (Government of India 2006, p. 1). It suggested that the gram panchayat should take the basic responsibility of reorganising and maintaining such records at the village level (ibid., p. 2). This recommendation is quite simple but nevertheless constitutes a landmark recommendation because it emphasises the potential of village-level data sources in the era of democratic decentralisation in rural India.

The Committee’s recommendation that the gram panchayat should “consolidate, maintain and own village level data” identifies, in effect, a new statistical domain – and one that opens up a new area for debate, discussion, and study.11 The recommendation itself was based on the finding that, in almost all the States and Union Territories, various types of village-level data are collected by local-level functionaries – such as the panchayat secretary, auxiliary nurse midwife (ANM), revenue officials (patwari), school teachers, child-care (anganwadi) workers, village headmen, knowledgeable persons, and others – on a regular basis, and maintained in their respective registers or records.12 At present, such village-level databases as are available at the PRIs often cannot be properly utilised because they are scattered; there is lack of coordination between the agencies responsible for them; the format and itemised details of different sources are not uniform; and updating and maintaining the data are irregular.13

Based on this finding, the Committee provided a framework for Village Schedules that contained a minimum number of selected variables on which data were to be collected, compiled, aggregated, and transmitted to the district level. The point here is that such village-level data are in existence before the information is filled into the Village Schedules. The Schedule is merely a framework or template for compiling statistics that have already been collected by the above-mentioned local-level functionaries.14

Thus, in a sense, the view of this Expert Committee on village-level data sources is in striking contrast to that of the Rangarajan Commission. While the Rangarajan Commission, on the one hand, had raised a serious alert over the degeneration of records maintained by government staff, patwaris, gram sevaks, or primary teachers at the farthest end of the government system, that is, at the level of the village (National Statistical Commission 2001, paras 14.6.1–14.6.4), the Expert Committee, on the other hand, found potential in some of the existing village-level records in the new era of democratic decentralisation in rural India.15 Due to a lack of attention by data users to village-level databases, there has been no intensive discussion of these data sources, and on their quality and usefulness. However, in order to empower the panchayats in the post-73rd Amendment regime, village-level databases must be a subject of discussion and debate.16

Methodology

Without an outline of gram panchayats’ data needs, we cannot evaluate what we have termed a new statistical domain. In this study, our method is to assess the data needs of a gram panchayat on the basis of the provisions of the Constitution (73rd Amendment) Act, 1992. We have described and classified the data needs of the gram panchayat on the assumption that State governments will legislate and devolve powers of self-governance and development to the panchayats as described in the Act (whether or not they have actually done so). The concerned provisions are Article 40 in Part IV (Directive Principles of State Policy), all Articles in Part IX (Panchayats), the Eleventh Schedule related to Article 243G, and Article 243 ZD in Part IXA (Municipalities) of the Constitution.

Therefore, the scope or boundaries of our study are slightly different from those of the Expert Committee on the BSLLD. We have identified the data needs of the gram panchayat on the basis of the constitutional requirements as a whole, whereas the Expert Committee identified these data needs on the basis of its terms of reference, that is, “for use in micro-level planning of various developmental programmes” (Government of India 2006, p. A-1).

We have examined the issue of gram panchayat-level databases in general, and also in the specific context of two villages, one in Maharashtra and one in West Bengal, both studied previously by the Foundation for Agrarian Studies (FAS).17 The first case study was of Warwat Khanderao gram panchayat in Buldhana district, Maharashtra. The second case study covered Raina gram panchayat in West Bengal and Bidyanidhi village in the jurisdiction of Raina gram panchayat.

First, we describe the background of the evolution of the new statistical domain in both gram panchayats. Secondly, we describe the village-level data that exist and the village-level data that are actually maintained by the gram panchayats. We describe the current status of the main data sources in the two villages. Thirdly, we describe the village-level databases that are required by gram panchayats in the post-73rd Amendment regime. In the light of the data requirements identified in our study, we discuss the potential of the village-level databases. We discuss how the main data sources in the jurisdiction of the two gram panchayats can be organised as databases to serve the data needs described in our study. We also evaluate the Village Schedule developed by the Expert Committee on BSLLD. Further, we discuss certain issues regarding the scope for new data, going somewhat beyond the proposed Village Schedule on BSLLD.

Within the jurisdiction of the above-mentioned gram panchayats, we identified village-level data sources that now help to fulfil the provisions of the Constitution (73rd Amendment) Act, 1992. We also made an assessment of their quality and usefulness.

The status of data sources at the point of collection and recording of data is a focal point of this study. Both the Expert Committee on BSLLD and the Rangarajan Commission have stressed the need to pay attention to data collection in all its dimensions.18 We looked into data sources at their “very roots, namely, at the very first stage of collection and recording of data” (National Statistical Commission 2001, para 14.3.10). We visited each gram panchayat and conducted interviews, at the gram panchayat offices and other official agencies located in the jurisdiction of the gram panchayats, about data sources and their uses at the gram panchayat or village level. We started the interviews using the simplified Village Schedules on BSLLD as a questionnaire. As a follow-up, we added to the questionnaire a few items regarding the additional data needs identified in our study. We also conducted interviews at the block-level offices of the gram panchayats. Panchayat officials helped us collect and check various documents and data used for the functions of the gram panchayat.

For an analytical discussion of the utility of gram panchayat-level databases, we need a clear idea of specific operational and activity-related responsibilities of the gram panchayat. We used as a reference, the information available on Activity Mapping (the term is explained elsewhere in this paper) at the State and Central levels in India. Since it is not possible to discuss the use of databases without an idea of concrete activities or schemes at the gram panchayat level, we also conducted interviews with panchayat officials about Activity Mapping at the village level.

Since census-type household surveys had already been conducted in Bidyanidhi and Warwat Khanderao by the Foundation for Agrarian Studies (FAS), we used FAS household data as a point of reference. This enabled us to assess the quality of some items of data available in the villages. As far as possible, we conducted micro-level discrepancy analyses, comparing each and every person or household with the corresponding person or household in the database of the census-type household surveys conducted by FAS.

This study primarily covers the period from 2005 to 2010. However, we conducted some follow-up surveys after 2010. As the reference period of our study is 2005–10, in West Bengal it covers the period during which the Left Front government, led by the Communist Party of India (Marxist), was in power.

As will be seen later, most of the data generated and used in the gram panchayat area are by-products of the administrative requirements of the panchayats themselves or other satellite State government agencies. The database generated in gram panchayats as by-products of such administrative requirements is thus the main area for discussion with respect to the new statistical domain.

These village data are fundamentally different from data generated by the Census of India and official sample surveys. Census data collected in India under the Census Act 1948 are “confidential.” This means that the filled-up census schedules are absolutely confidential, and cannot be disclosed to any individual or entity, nor be subjected to scrutiny. Similar confidentiality rules apply to official sample surveys. Thus, panchayats or other government offices cannot use household or individual records from the Census of India or official sample surveys for administrative purposes (although aggregative data at the village or higher administrative levels are available and may be used). However, the administrative functions of panchayats call for specific information on households and individuals. Such information, which cannot be obtained from the Census of India and other official surveys, has to be gained from other administrative records available with the gram panchayat. For example, the list of below-poverty-line (BPL) households for a village is used not only to find out the number or percentage of such households, but also to select individual beneficiaries for various poverty alleviation programmes. The Second Administrative Reforms Commission of the Government of India noted that:

Improving the quality of life of citizens by providing them civic amenities has been the basic function of local governments ever since their inception and it continues to be so even today. Local governments are ideally suited to provide services like water supply, solid waste management, sanitation, etc., as they are closer to the people and in a better position to appreciate their concerns. . . . [E]ven economic principles state that such services are best provided at the level of government closest to the people. However, the performance of a large number of local bodies on this front has generally been unsatisfactory. (Government of India 2007, p. 8)

This study deals with not only aggregate data generated as by-products of administrative requirements in the gram panchayat area, but also with unit-level (household and individual) data for administrative requirements. There are at least two important reasons for studying such unit-level data.

First, the status and quality of such unit-level data have direct consequences for the quality of aggregate data generated from them. Secondly, unit-level information on village society is of the utmost importance for members of the gram panchayat, which is the administrative unit that is closest to the residents of a village. Panchayat and gram sabha members require unit-level data in order to carry out the tasks of public administration that are within their respective powers.

Policy decisions will have to be taken with regard to the persons and functionaries to whom access is granted to unit-level data that is to be used for administrative purposes.19 The particular focus of this study, however, is the potential use of such unit-level data. As these unit-level databases are ready-to-aggregate statistics,20 we deal with them as a part of the statistical databases under consideration.

We use the term “administrative statistics” broadly, and, in addition to the unit-level data, we also discuss financial accounting data in this regard. Although accounting data are often not a matter of concern for the official statistician, we believe that it is not appropriate to exclude accounting data from administrative records when we study overall panchayat statistical records, since accounting data are an integral part of the panchayat records system.

A Landmark Report

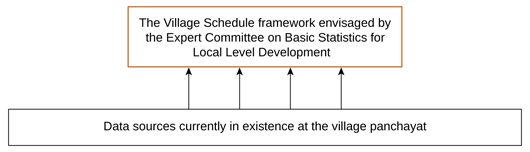

As mentioned above, the most important work in recent years on the subject of this enquiry is that of the Expert Committee on Basic Statistics for Local Level Development (BSLLD) (Government of India 2006). The essential point of this work is that a set of data sources is indeed in existence in the village before the Village Schedule is filled up. That is to say, a set of village-level data sources exists that can provide the items of data listed in the Village Schedule, though these sources are scattered and lack proper coordination.

Our enquiry is greatly influenced by the work of the Expert Committee and its findings with respect to gram panchayat-level databases. In fact, as mentioned, we started our interviews by using the simplified Village Schedules on BSLLD as a questionnaire to study various data sources in the field in the two study villages. We independently conducted a direct survey of the domain, represented in the diagram below by the phrase enclosed by the thick-ruled box.

In the course of a wide-ranging review of village-level data sources and various contributions to the Indian literature on the panchayat system, we felt the necessity to broaden our scope to discuss multiple aspects of this statistical domain in India. The terms of reference of the Expert Committee on BSLLD included

the development of a system of regular collection of data on a set of core variables/indicators, which should be compiled and aggregated at local levels for use in micro-level planning of various developmental programmes.21

The Committee identified data needs “for use in micro-level planning” that are, most certainly, crucial to the decentralisation process initiated by the 73rd Amendment to the Constitution. Our study describes this set of data needs as Data Needs III.

However, some contributions to the Indian literature on panchayats deal with certain other kinds of village-level data as well. For example, the Eleventh Central Finance Commission and the subsequent Central Finance Commissions have repeatedly recommended the creation of databases on the finances of local bodies for the post-73rd Amendment regime.22 If the panchayats are not accountable for their financial management, people’s trust in panchayats would decline. Furthermore, the Twelfth Central Finance Commission states that

the absence of data necessary for a rational determination of the gap between the cost of service delivery and the capacity to raise resources makes the task of recommending measures for achieving equalisation of services almost impossible. (Twelfth Finance Commission 2004, p. 154)

The Third State Finance Commission of West Bengal claimed that “the information system should be part of the general statistical information system necessary for planning and delivering public services” (Third State Finance Commission West Bengal 2008, p. 35). At the village we found that the core parts of registers in a gram panchayat were maintained to track the allocation and expenditure of funds, and assess the progress of different schemes. But, as shown below in the section on “Two Gram Panchayats and Villages,” the Village Schedule on BSLLD does not include data items such as financial condition of the gram panchayat concerned. Our study describes this set of data needs as Data Needs II.

To take another example, the Self-Evaluation Schedule in West Bengal contains data items concerning the status of gram sabha and gram panchayat personnel, the status of gram panchayat buildings and facilities, and the status of activities of the gram panchayat and gram sansads (Government of West Bengal 2008). The Village Schedule on BSLLD does not contain data items of this nature on the panchayat itself. Our study describes this set of data needs as Data Needs I.

It is important to remember that the Village Schedule as envisaged in BSLLD is essentially compiled from secondary aggregate data and not by conducting a unit-to-unit survey. Since the gram panchayat is the institution nearest to residents of the village, unit-level data (or lists of units) – such as lists of households, lists of persons, lists of events, lists of facilities or establishments, lists of plots or holdings, and so on – are essential for the institution.

Outline of Data Needs of Panchayats

This study thus attempts to broaden the scope of discussion of data needs under the decentralisation initiated by the Constitution (73rd Amendment) Act, 1992 by taking into account the provisions of the Amendment itself. We have interpreted the data needs on the assumption that State governments will legislate and devolve powers of self-governance and development to the panchayats in the manner envisaged in the Constitution. According to Article 243G of the Constitution:

Subject to the provisions of this Constitution, the Legislature of a State may, by law, endow the Panchayats with such powers and as may be necessary to enable them to function as institutions of self-government and such law may contain provisions for devolution of powers and responsibilities upon Panchayats at the appropriate level, subject to such conditions as may be specified therein.

Here, the word “may” implies that the powers and authority given to PRIs are at the discretion of State governments, and are a matter of political debate in the Legislature of each State. Although State governments may or may not legislate and devolve powers of self-governance and development to the panchayats as described in the 73rd Amendment, in this paper we discuss the data needs of gram panchayats on the assumption that they will do so.

The data needs of panchayats, assuming that the powers devolved upon them come into full play, have been identified by us as follows:

|

Data Needs I This category covers data required for self-governance. Within this, a special component can be identified, that is: Data Needs Ia This covers data required for managing the transition to devolution as envisaged in the Constitution. In addition, in practice, data generated or used by line departments and other agencies working in the panchayat’s jurisdictions and still working independently of the panchayati raj set-up are required by the panchayats, especially to manage the transition to constitutional devolution. These data needs are described in the Indian literature in sources such as the report of the Second Administrative Reforms Commission and the Planning Commission, and in the Manual for Integrated District Planning, 2008, of the Planning Commission (Government of India 2008b). Data Needs II This category covers data required for matters of public finance. Data Needs III This category covers data required for micro-level planning (and plan implementation) for economic development and social justice. |

Each of these sets of data has its own logic and deserves separate consideration. We need to discuss the multiple aspects of each of these sets of data needs in the new statistical domain.

Two Gram Panchayats and Villages

As mentioned above, we have studied the new statistical domain in the light of the experience of two study villages, Warwat Khanderao gram panchayat in Maharashtra and Raina gram panchayat in West Bengal, and Bidyanidhi village in the jurisdiction of Raina gram panchayat. As mentioned earlier, Raina village was studied during the period that the Left Front was in power. The Communist Party of India (Marxist) and other constituents of the Left Front also had a majority of seats in the gram panchayat.

Maharashtra is part of the erstwhile temporarily settled or ryotwari areas that were cadastrally surveyed, and where a land revenue officer (patwari) collects and revises village-level land records annually. On the other hand, West Bengal is part of the erstwhile permanently settled or zamindari areas that were cadastrally surveyed, but where no patwari agency exists at the village level. The land record system and historical systems of land revenue were substantially different in the two gram panchayats. The share of land revenue in the total revenue of the panchayat was quite high in Maharashtra compared to West Bengal. But the differences went further than that. The Maharashtra State government has traditionally placed emphasis on the district as the basic unit of planning and development. In fact relatively large resources are allocated to the district panchayats (zilla parishads, ZPs) in Maharashtra. According to the Audit Report (Local Bodies) in Maharashtra of the Comptroller and Auditor General (C&AG) of India and the Report of the Examiner of Local Accounts in West Bengal, the receipts of panchayats solely at the zilla parishad level in Maharashtra were Rs 11,111 crore in 2007–08, whereas the total receipts of all three tiers of panchayati raj institutions in West Bengal in the same period were only Rs 3,343 crore. However, the C&AG of India found in the audit of the zilla parishad records in Maharashtra “many cases of failure to refund unspent balances leading to huge blocking of public money for no purpose” (Comptroller and Auditor General of India 2008, p. 32). The C&AG therefore recommended that the “accumulation of huge funds with ZPs needs to be examined” (ibid., p. 42). By contrast, more resources were allocated to the gram panchayat level in West Bengal than in Maharashtra, that is, a total of Rs 2,099 crore for the former and a total of Rs 1,059 crore for the latter in 2007–08. In fact, the State Finance Commission of West Bengal was of the view that “there is a growing shift in the focus of development activities towards the GP level under the evolving decentralised planning environment.”

Further, sector-wise receipts and expenditures of PRIs in West Bengal indicated that alleviating poverty was a core activity of the panchayats in the State (Government of West Bengal 2009, p. 9). This was in contrast to panchayats in Maharashtra, where expenditure incurred on poverty alleviation was very limited.

With respect to data management, there was an essential difference between Maharashtra and West Bengal. The Expert Committee on BSLLD pointed out that data-sharing mechanisms between different agencies working at the gram panchayat level did not function well in Maharashtra villages. The Committee stated:

There are no formal data-sharing mechanisms between different agencies working at Gram Panchayat, Tehsil or District levels. . . . The channels of reporting in the case of different functionaries at Gram Panchayat, Block Development Office and District Panchayat Office are through the respective line of control of the respective departments. The reports being received by different departments are generally not being integrated at any stage. (Government of India 2006, p. 25)

In contrast, there were some statistical areas in West Bengal that had data-sharing mechanisms. Interlinked health and child-care systems among the gram panchayat, Integrated Child Development Services (ICDS) centre, and Block Health Centres in West Bengal made data-sharing between these agencies possible. For example, at the Fourth Saturday Meeting at gram panchayats in West Bengal, data on institutional births were collected from health department officials and on the number of children born at home from the ICDS worker, and the list was compiled at the gram panchayat office to prepare their monthly chart. No such formal data-sharing mechanism existed in the Maharashtra village.

There was thus a difference between Maharashtra and West Bengal in institutional coordination among different agencies working in the gram panchayat. This difference also affected the status of the statistical databases of the two gram panchayats.

Basic Structure of Main Data Sources at the Village Level

Next, we describe the current status of the main data sources in the two study villages. We discuss the kinds of village-level data that exist, and the village-level data that are actually maintained by the panchayats.

As the Rangarajan Commission noted, the main sources of statistics in India, as elsewhere, are (a) administrative records – generally consisting of statutory administrative returns and data derived as a by-product of general administration; and (b) other important sources, namely, censuses and sample surveys.23 Indeed this dichotomy is quite universal. For example, the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) states that

there are two basic mechanisms for collecting economic data. They are, access to data already being collected for administrative purposes, and direct surveys by the statistical office.24

However, this dichotomy was not so clear at the village level. There were some data sources of an intermediate type between (a) administrative records and (b) typical census-type surveys. As will be seen later, some administrative records, such as the ICDS village survey register, were established and regularly updated through census-type survey operations. Some census-type surveys, such as the Below Poverty Line (BPL) census, were used in the PRIs for administrative purposes such as BPL-household identification. In this way, most of the data generated and used in the gram panchayat areas were by-products of the administrative requirements of the panchayats themselves or other satellite State government agencies.

This paper therefore classifies these data sources according to how deeply and closely they were related to the core system of the gram panchayat. That is to say, they could be classified according to whether or not they were generated inside the gram panchayat system, and, where generated outside the gram panchayat system, how far they came under the gram panchayat’s control. Consequently, we sometimes found administrative records in the villages that were generated from census-type surveys.

The main sources of data at the gram panchayat level and below can be classified as follows:

1. Registers and records collected and

maintained by the gram panchayat.

2. Census-type surveys independently conducted by PRIs (we

found this at Raina, the gram panchayat in Barddhaman district, West Bengal,

and not in Warwat Khanderao, the gram panchayat in Buldhana district).

3. Village-level registers and records collected

and maintained by other agencies, such as:

- Village ICDS (or anganwadi) registers

- Village school registers

- Records at the Primary Health Centre (only in Raina gram panchayat)

- Patwari records (only in Warwat Khanderao) or records at the Block Land and Land Reform Office (only in Raina gram panchayat)

- Others.

4. Census-type surveys organised by Central or State governments, such as:

- the BPL census, including the Rural Household Survey (RHS), Socio-Economic and Caste Census (SECC)

- the Census of India

- Others.

Besides the data sources described above, there were administrative reports concerning the gram panchayats or villages. These reports were compiled from secondary data, the original sources of which have been listed in 1 to 4 above. The administrative reports were submitted to the block or zilla parishad, and sometimes upward to the State or Central government. The information in these reports were usually not collected by conducting unit-to-unit surveys, such as household-to-household surveys, facility-to-facility surveys or plot-to-plot surveys, etc. It was usually gathered from the records maintained by village-level functionaries or from common knowledge among village people. Such administrative reports were as follows:

5. Administrative reports of the gram panchayat such as:

- the Village Schedule

- village-level amenities data (Village Directory data) in the District Census Handbook

- the Self-Evaluation Schedule (at Raina only)

- Others.

Next, we introduce two selected topics concerning the new statistical domain in rural India.

People’s List

People living in the jurisdiction of the panchayat are the main actors in the panchayat. The panchayat, especially the gram panchayat and sub-gram panchayat bodies, is the nearest available administrative institution for people living in villages. Therefore, the panchayat is expected to be a democratic and people-oriented local government.

The panchayat has responsibilities with regard to each and every resident in its jurisdiction, and sometimes with regard to certain groups or individuals in specific social groups, in order to improve their capabilities. In order to be a people-oriented local government, the panchayat requires a comprehensive People’s List; that is to say, a list of all persons and households in its jurisdiction. The panchayat needs this list despite the fact that the Population Census covers every village, because unit-level records produced by the Population Census are not available to it. Without a comprehensive list of residents in its jurisdiction, the panchayat’s overall public policies would be inefficient or discretionary, and less objective. It would be difficult for the panchayat to formulate its public policies in relation to its residents. At present, however, no such comprehensive list of people – that we refer to, hereinafter, as a “People’s List” – is available in the panchayat office. There is no official list of each and every resident in the panchayat’s jurisdiction.

The Gram Sevak of Warwat Khanderao argued that he could use the electoral roll together with the Property Tax Register (House Tax Register), if necessary, to identify households and individuals in the gram panchayat. These lists can be used particularly in the identification of target beneficiaries for government schemes.

The electoral roll is a core list that covers the residents of a village. It contains information on the identification number, full name, name of father, house number, age, and sex of each voter. However, it includes only adults and therefore does not cover all residents. For example, out of 1,308 persons in the FAS list for Warwat Khanderao, 564 persons were under 20 years old. In addition, the electoral roll may also include persons temporarily or permanently living outside the village. For example, the number of voters in the electoral roll of Warwat Khanderao was 889 as against a total population of 744 aged 20 and above. Out of 744 persons in the voters’ list, 654 persons were identified in the FAS data.

The Property Tax Register contains information on each and every “house” in the panchayat’s jurisdiction, together with its owner and “house number,” but it does not contain any information on members of the owner’s household. Furthermore, if more than one “household” (a group of persons normally living together and taking food from a common kitchen) or “family” lives in the house, any household other than the owner’s household would not be covered by the Property Tax Register. Therefore, it does not necessarily cover all the heads of households. For example, in Warwat Khanderao the number of “house numbers” given to voters was only 209 when matched with the FAS database, but the actual number of families in the FAS database matched with the electoral roll was 239. The reason is that some “house numbers” were given to more than one FAS family. The number of “house numbers” given to more than one FAS family was 37, whereas the number of FAS families to which more than one “house number” was given was 16. Thus quite a few families were absent from the Property Tax Register.

Table 1 Comparison of electoral roll and FAS survey data, Warwat Khanderao, 2007

| No. of FAS families with house numbers in the electoral roll | 239 |

| No. of house numbers of FAS families matched with the electoral roll | 209 |

| No. of FAS families with more than one house number | 16 |

| No. of house numbers given to more than one FAS family | 37 |

Sources: Electoral roll obtained from Warwat Khanderao gram panchayat office; Foundation for Agrarian Studies (FAS) village survey database.

Being the institution nearest to the people of a village, the gram panchayat requires not only aggregate data but also unit-level records for data retrieval. In fact, in an interview, a panchayat leader at Raina stated that a type of People’s List would be most desirable for his panchayat’s activities. Thus, in this paper, we examine some records that have the potential to function as comprehensive lists of residents in the jurisdiction of a panchayat, that is, the Integrated Child Development Services (ICDS) Village Survey Register and the village-wise BPL/APL household list of the BPL Census.

The BPL Census 2002 has already been widely criticised by the rural poor and their organisations, and by scholars. There is a suspicion that some poor households were excluded from the BPL list and some non-poor households included. There is widespread discontent among village residents regarding the BPL list generated from the BPL survey data. On the basis of a micro-level discrepancy analysis, comparing each head of household in the BPL list with the corresponding person in the FAS list, we found that some parameters estimated by the BPL Census were very inaccurate. However, as will be seen below, the coverage of the BPL/APL persons of the BPL Census was in itself not too bad.

The more frequently updated a People’s List is, the better it is for use. In this respect the ICDS Village Survey Register is preferable as a core People’s List as it is updated regularly. On the other hand, although the BPL Census database is not updated regularly, it is available in digitised format. In addition, some of the questions incorporated in the BPL Census questionnaire are independent of the daily operations of public administration. In the context of mentioning the digitised database generated from the BPL Census 2002 (Rural Household Survey in West Bengal), the Panchayat and Rural Development Department of West Bengal stated that the household database of the Rural Household Survey had been helpful in the following ways. It could help

- PRIs or the district authority to get a ready list of all rural households and their socio-economic status;

- identify and generate a list of socially vulnerable families;

- generate lists of potential beneficiaries for government and PRI-sponsored programmes;

- generate GIS maps for grassroot-level planning for economic development and social justice; and

- make available information on socio-economic conditions to the public at large for better social audit.

The panchayat leader at Raina who told us in an interview that a type of People’s List is desirable for his panchayat’s activities also said that the village-wise all-household list (BPL/APL household list) of the Rural Household Survey is not too bad for their use. He said so notwithstanding his discontent with the accuracy of the list of BPL households and with the scores obtained by households on each of the parameters.

Using the FAS database as a point of reference, we made an assessment of the “candidate lists,” so to speak, for the People’s List; that is, the ICDS Village Survey Register and the BPL Census 2002 (or the Rural Household Survey). The number of persons in these two lists are shown in Table 2 and Table 3.

We emphasise that some discrepancies were inevitable because of differences in the reference period in the three data sets used. The FAS surveys in Warwat Khanderao and Bidyanidhi were conducted in 2007 and 2005 respectively. The ICDS register data was collected in both villages in 2009 and hence the data in these registers were updated till 2009. BPL census data in the two villages pertained to 2003 in Warwat Khanderao and 2005 in Bidyanidhi. Some of the discrepancies arising out of the differences in reference years, particularly with regard to Integrated Child Development Services (ICDS) registers, could easily be identified and are reported in our analysis (see, for example, Table 8). However, some of the discrepancies originating from the difference in reference years could not be identified and isolated, and this was particularly true for discrepancies between the FAS and BPL census databases in Warwat Khanderao.

The BPL Census database for Bidyanidhi contains a complete list of all households and the scores obtained by each household on each of the parameters used for identification of the poor. However, the database does not list the household members of each household. Of the 151 households listed in the Census database, information on household members is available for only 17. For this reason, the data could not be used for our micro-discrepancy analysis and the number of persons in the BPL Census database is blank in Table 3.25

Table 2 Total number of persons in different databases, Warwat Khanderao

| FAS survey database | 1308 |

| BPL Census database | 1322 |

| ICDS Village Survey Register | 1319 |

Sources: BPL Census database available from Ministry of Rural Development, http://bpl.nic.in/; household register obtained from ICDS centre, Warwat Khanderao.

Note: The reference months/years of the surveys are as follows: FAS Survey database: May 2007; BPL Census database: June 2003; ICDS Village Survey Register: 2005.

Abbreviations are explained in the “Abbreviations and Glossary” section at the end of the article.

Table 3 Total number of persons in different databases, Bidyanidhi

| FAS survey database | 643 |

| BPL Census database | – |

| ICDS Village Survey Register | 896 |

Sources: BPL Census database available from Ministry of Rural Development, http://bpl.nic.in/; household register obtained from ICDS centre, Bidyanidhi.

Notes: The BPL Census database for Bidyanidhi does not list the household members of each household. For this reason, the data could not be used for our micro-discrepancy analysis and the number of persons in the BPL Census database is blank in the table.

The reference months/years of the surveys are as follows: FAS Survey database: June 2005; BPL Census database (conducted in Raina as the Rural Household Survey): 2005; ICDS Village Survey Register: 2005.

Abbreviations are explained in the “Abbreviations and Glossary” section at the end of the article.

For the purpose of assessment of these candidate lists, we conducted a micro-level discrepancy analysis, comparing each and every person and household in these lists with the corresponding person and household in the database collected from census-type household surveys conducted by the FAS. We tried to match each and every person and household in these candidate lists with the corresponding person and household in the FAS (or PARI – Project on Agrarian Relations in India) database. First, we tried to match them using their names, ages, etc. We then conducted a follow-up interview for unmatched cases with persons in the village, including village-level functionaries. On the basis of the interviews we corrected the spellings of names and tried to match them again as far as possible. There was no standard Romanisation of the Hindi, Marathi, or Bengali scripts. There were also entry errors and spelling mistakes. Nicknames were sometimes used for children. Therefore, it was not easy to undertake the data-matching. From the follow-up interviews we found various reasons for the non-match. Finally, we examined the overall matching status of person-wise and household-wise lists.

The “matching status” of each of the two person-wise lists with the persons list of the FAS database is shown in Table 4 and Table 5. In the tables, row entries show the matching status of each list in the left column with each list in the first row. As the list shown in the left column is the reference point, the matching status of, say, x list with y list is not identical to the matching status of y list with x list.

Table 4 Discrepancy matrix of number of persons in different databases, Warwat Khanderao

| Type of database | FAS survey | BPL Census | ICDS Village Survey Register | |||

| Matched | Not matched | Matched | Not matched | Matched | Not matched | |

| FAS survey database | – | – | 973 | 335 | 956 | 352 |

| BPL Census database | 973 | 349 | – | – | 908 | 414 |

| ICDS Village Survey Register | 956 | 363 | 908 | 411 | – | – |

Sources: FAS village survey database; Ministry of Rural Development, http://bpl.nic.in/; household register obtained from ICDS centre, Warwat Khanderao.

Note: Abbreviations are explained in the “Abbreviations and Glossary” section at the end of the article.

Table 5 Discrepancy matrix of number of persons in different databases, Bidyanidhi

| FAS survey | ICDS Village Survey Register | |||

| Matched | Not matched | Matched | Not matched | |

| FAS survey database | – | – | 632 | 11 |

| ICDS Village Survey Register | 632 | 264 | – | – |

Sources: FAS village survey database; Ministry of Rural Development, http://bpl.nic.in/; household register obtained from ICDS centre, Bidyanidhi.

Note: Abbreviations are explained in the “Abbreviations and Glossary” section at the end of the article.

The person-wise People’s Lists in the BPL Census database and the ICDS Village Survey Register in Warwat Khanderao were not adequate with respect to data quality. They did not properly document 20 to 30 per cent of the village population. There were inaccuracies in the records with respect to many children, elderly widows, Muslim persons, and some others. Some children’s names were not recorded in the Village Survey list and some names were probably inaccurately spelt. It was sometimes difficult to identify the families to which aged widows belonged: they were sometimes recorded as family members of one of their children, and sometimes as one-person households. Therefore, the matching status of children under 10 years and women older than 70 was not good, as shown in Table 6. The matching status of Scheduled Caste (SC) and Scheduled Tribe (ST) persons was not particularly bad, but the status of Muslim persons was not good, as shown in Table 7.

Table 6 Number of individuals reported in BPL Census database as percentage of individuals reported in FAS survey database, by age-group, Warwat Khanderao

| Age (years) | Female (per cent) | Male (per cent) | Total (per cent) |

| 5 and below | 26.1 | 24.3 | 25.2 |

| 5–10 | 63.9 | 71.9 | 68.0 |

| 10–15 | 81.5 | 80.0 | 80.8 |

| 15–20 | 75.6 | 92.5 | 83.7 |

| 20–25 | 40.0 | 84.2 | 61.5 |

| 25–30 | 84.0 | 69.6 | 76.4 |

| 30–50 | 86.1 | 92.4 | 89.2 |

| 50–55 | 84.2 | 85.0 | 84.6 |

| 55–60 | 82.1 | 95.7 | 88.2 |

| 60–65 | 73.7 | 96.3 | 87.0 |

| 65–70 | 80.0 | 100.0 | 89.5 |

| 70 and above | 27.3 | 87.5 | 63.0 |

| TOTAL | 69.6 | 79.1 | 74.4 |

Sources: FAS village survey database; household register obtained from ICDS centre, Warwat Khanderao.

Note: Abbreviations are explained in the “Abbreviations and Glossary” section at the end of the article.

Table 7 Number of individuals reported in Integrated Child Development Services (ICDS) and Below Poverty Line (BPL) Census databases as percentage of individuals reported in Foundation for Agrarian Studies (FAS) database, by caste/religious group, Warwat Khanderao

| Caste/religious group | ICDS Village Survey Register (per cent) | BPL Census (per cent) |

| Muslim | 52.6 | 68.5 |

| Nomadic tribe | 72.9 | 79.2 |

| Other Backward Class (OBC) | 80.6 | 75.0 |

| Scheduled Caste (SC) | 86.8 | 77.2 |

| Total | 72.9 | 74.4 |

Sources: FAS village survey database; household register obtained from ICDS centre, Warwat Khanderao; Ministry of Rural Development, http://bpl.nic.in/.

Note: Abbreviations are explained in the “Abbreviations and Glossary” section at the end of the article.

The person-wise list in the ICDS Village Survey Register in Bidyanidhi was of high quality. As shown in Table 5, it covered most persons in Bidyanidhi, that is, 98.3 per cent of persons in the FAS survey database on Bidyanidhi. The information was updated regularly. Non-matched cases in the ICDS Village Survey Register were as many as 264. However, that is not necessarily a sign of the weakness of this Register. The current status of most of these unmatched cases is specified in the Register, as shown in Table 8. In Bidyanidhi, even after the ICDS Village Survey Register was updated every five years, a lot of information on births, deaths, marriages and migrations were added to and modified in it.

Table 8 Reasons for discrepancies between list of individuals in ICDS database and FAS database, Bidyanidhi

| Reason | Number of individuals |

| Born after FAS survey | 49 |

| Died before FAS survey | 29 |

| Married and left village | 29 |

| Married into village after survey | 28 |

| Non-resident | 95 |

| Other | 6 |

| Unspecified | 28 |

| Total | 264 |

Sources: FAS village survey database; household register obtained from ICDS centre, Bidyanidhi.

Note: Abbreviations are explained in the “Abbreviations and Glossary” section at the end of the article.

It is more difficult to undertake household-to-household matching than person-to-person matching. As far as a household-wise or family-wise People’s List is concerned, the numbers of all families in these candidate lists are shown in Table 9 and Table 10. Unlike the number of all persons, the number of all households varied considerably depending on the lists. A group of persons living together could be considered a joint family, or as sub-divided into several nuclear families. Where a married son lived together with his parents and others, he and his family could be either regarded as members of the larger joint family or as forming a separate household. A similar problem arose with elderly persons living with their children. Therefore, the size of household varied depending on the interpretation of the data collector. (The FAS surveys kept closely to the specified official definition.)

Table 9 Number of households recorded in different databases, Warwat Khanderao

| Database | No. of households |

| FAS survey | 250 |

| BPL Census | 306 |

| ICDS Village Survey Register | 295 |

| Census of India 2001 | 286 |

| Census of India 2011 | n.a. |

Sources: FAS village survey register; Ministry of Rural Development, http://bpl.nic.in/; household register obtained from ICDS centre, Warwat Khanderao; Census of India.

Note: Abbreviations are explained in the “Abbreviations and Glossary” section at the end of the article.

Table 10 Number of households recorded in different databases, Bidyanidhi

| Database | No. of households |

| FAS survey | 142 |

| BPL Census | 151 |

| ICDS Village Survey Register | 109 |

| Census of India 2001 | 131 |

| Census of India 2011 | n.a |

Sources: FAS village survey register; Ministry of Rural Development, http://bpl.nic.in/; household register obtained from ICDS centre, Bidyanidhi; Census of India.

Note: Abbreviations are explained in the “Abbreviations and Glossary” section at the end of the article.

Furthermore, the size of household is positively correlated to the BPL score. It is likely that the sub-division of a household leads to a lower BPL score, which causes a respondent bias among persons who want BPL cards. Therefore, the size of household in the BPL Census list tends to be larger than in other lists.

The matching status between two household-wise lists and the household list of the FAS database is shown in Table 11 and Table 12. In the tables, row entries show the matching status of each household list in the left column with each household list in the first row. (A matched household refers to cases where at least one household member of both households matches, and does not necessarily mean that all household members match in both lists.)

Table 11 Discrepancies in number of households recorded in different databases, Warwat Khanderao

| Database | FAS survey | BPL Census | ICDS Village Survey Register | |||

| Matched | Not matched | Matched | Not matched | Matched | Not matched | |

| FAS survey | – | – | 231 | 19 | 200 | 50 |

| BPL Census | 241 (230)* | 65 (76)* | – | – | 230 | 76 |

| ICDS Village Survey Register | 221 | 74 | 244 | 51 | – | – |

Sources: FAS village survey database; Ministry of Rural Development, http://bpl.nic.in/; household register obtained from ICDS centre, Warwat Khanderao; Census of India.

Notes: Matched household does not mean that all household members match, but that more

than one household member of each household matches.

*Matched head of household in BPL Census list

found in the FAS survey persons list.

Abbreviations are

explained in the “Abbreviations and Glossary” section at the end of the

article.

Table 12 Discrepancies in number of households recorded in different databases, Bidyanidhi

| Database | FAS survey | BPL Census | ICDS Village Survey Register | |||

| Matched | Not matched | Matched | Not matched | Matched | Not matched | |

| FAS survey | – | – | 133* | 9* | 138 | 4 |

| BPL Census | 139* | 12* | – | – | # | # |

| ICDS Village Survey Register | 99 | 10 | # | # | – | – |

Sources: FAS village survey database; Ministry of Rural Development, http://bpl.nic.in/; household register obtained from ICDS centre, Bidyanidhi.

Notes: * This represents matches between heads of

household in the BPL Census list and the list of all household members in the

FAS survey database. If the head of household in the BPL Census list is found

among the household members in the FAS survey database, the household is

considered as a matched household. More than one head of household in the BPL

Census list can be matched with a household in the FAS survey database.

# The

micro-discrepancy analysis was not carried out.

Abbreviations are

explained in the “Abbreviations and Glossary” section at the end of the

article.

As observed above, person-to-person matching is not as difficult as household-to-household matching.

During our study, we found a data-sharing mechanism in Bidyanidhi that contributed to the high quality of its ICDS Village Survey Register. In West Bengal, the Block Health Centre, ICDS centres and the panchayat formed an interlinked health and child-care system. A “Fourth Saturday Meeting” was held every month at the gram panchayat office with the ICDS supervisor, the ANM and health supervisor, and panchayat officials present. A monthly data-sheet was prepared that recorded the number of births and deaths, cases of morbidity, and the status of sanitation and drinking water supply in the gram panchayat. On the basis of this interlinked health and child-care system, data-sharing among these agencies was possible in Bidyanidhi. The data-sharing mechanisms made it possible also to check the reliability of data from different sources.

If the gram panchayat were to designate a core list of people and check its reliability on the basis of a data-sharing mechanism among different data sources, the quality of data in the People’s Lists could be improved in Warwat Khanderao as well. The ICDS Village Survey Register or database from census-type surveys such as the BPL Census can serve as a core population list. Besides the BPL Census, other census-type surveys such as those organised by PRIs, Central or State governments can also be candidates for the population list.

The following person-wise lists are available in the village as check-lists to validate and update the core lists of its people:

- Electoral roll and Property Tax Register (House Tax Register)

- Records at the Primary Health Centre

- Birth and Death Register of the Civil Registration System (CRS)

- Records at village school (especially where an annual survey is conducted by school teachers on all households in the village)

- The Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme (MGNREGS) register.

We suggest that there are some possible ways of generating population lists through data-sharing:

Alternative (1). The gram panchayat can designate and coordinate the ICDS Village Survey Register as the core list of the people of the village. ICDS (anganwadi) workers or a group of officials in an interlinked health and child-care system can then update it regularly. Databases from census-type surveys such as the BPL Census can be used to check its reliability. Further, the various check-lists mentioned above can be used to validate and update the ICDS Village Survey Registers.

Alternative (2). The gram panchayat can initially designate a database from a census-type survey such as the BPL Census (or the Socio-Economic and Caste Census, SECC, 2011) as being the core list of the population. ICDS (anganwadi) workers or a group of officials in an interlinked health and child-care system can then update the list regularly. Subsequently, the various check-lists mentioned above can be used to validate and update the initial core list of the people.

Alternative (3). As the project to create the National Population Register (NPR) is now on-going, the gram panchayat can designate the NPR as the core list of the people. The NPR is a process of mandatory registration of all usual residents of a locality under the Citizenship Act 1955 and the Citizenship (Registration of Citizens and Issue of National Identity Cards) Rules, 2003. The first phase of the project, which required the registration of usual residents through a door-to-door survey, was completed with the first phase of Census 2011 in April–September 2010. However, collection of biometric information and issuing citizenship identity cards under the project remain a controversial issue due to the fact that the collection of biometrics does not have statutory backing in the Citizenship Rules 2003, and the obvious overlap between the NPR and the Unique Identification Authority of India (UIDAI) project of the Government of India, which also entails collecting biometric data and issuing a unique identification number to all citizens of the country.

The ICDS Village Survey Register is not recorded digitally, whereas the BPL Census database and some of the checklists mentioned above are maintained in digitised form. It would be useful for the gram panchayat if the database from the ICDS Village Survey Register was digitised at the block or district level. It would be useful even as a paper document if there were comment columns in which to record additional information on each record. In fact panchayat officials in Raina regarded the registers maintained by ICDS workers highly, even though they were not digitised.

Civil Registration System

Although the Rangarajan Commission stated that the Civil Registration System (CRS) has the potential to provide estimates of vital events at the local level (National Statistical Commission 2001, para 2.7.8.), vital village-level records in the existing CRS are not necessarily related to people resident in the area. The existing CRS is often out of focus as databases required for the self-governance of gram panchayats.

There are two ways of registering vital events: at the place of occurrence or at the place of usual residence (United Nations 2001, p. 59). The existing CRS determines the place of registration according to the place of occurrence of vital events. Vital events of residents occurring outside the jurisdiction of the gram panchayat is not registered in the CRS, even if that resident usually lives in the gram panchayat area. For example, the CRS of a gram panchayat does not register children born outside the jurisdiction of the gram panchayat because their mothers may return temporarily to their native villages for delivery or go to nearby towns for institutional delivery. They are registered outside the gram panchayat area in which their usual residences are located. In this respect, the recording principle of birth records in the CRS does not suit self-government of the gram panchayat. The birth records in the CRS are not entirely related to people resident in the area and are not focused on the people there.

Table 13 Details of registration of children of age 5 years and below, Warwat Khanderao, May 2007

| Category | Number (%) |

| All children less than or equal to age 5 in the FAS database for 2007 | 130 (100.0%) |

| Registered births in the CRS at Warwat Khanderao or elsewhere | 111 (85.4%) |

| Registered births in the CRS at Warwat Khanderao | 29 (22.3%) |

| Registered births in the CRS elsewhere outside Warwat Khanderao | 82 (63.1%) |

| Unregistered births in the CRS neither at Warwat Khanderao nor elsewhere | 18 (13.8%) |

| Other | 1 (0.8%) |

| Registered births in the CRS at Warwat Khanderao but not in the FAS database for 2007 | 40 |

| Mothers who came to Warwat Khanderao for delivery | 23 |

| Other | 17 |

Sources: FAS village survey database; Civil Registration Sysytem (CRS) data.

Note: Abbreviations are explained in the “Abbreviations and Glossary” section at the end of the article.

Using the FAS database as a point of reference, we conducted a micro-level discrepancy analysis, comparing each and every birth event recorded in the CRS in Warwat Khanderao gram panchayat in the years from 2002 to 2007 with the corresponding person in the FAS database – that is, all children in the age-group 5 years and below in the FAS database. Furthermore, we conducted interviews with all households in which children were born in the years from 2002 to 2007, and whose names were not in the CRS but present in the FAS database (Okabe and Surjit 2012).

The major fact that emerges out of this assessment is that, even if we assume 100 per cent registration, the CRS gives information only about births occurring within the village, whereas in most cases mothers go to their native villages or for institutional delivery to the nearest town. As shown in Table 13, out of 130 children in the 0–5 age-group in 2007 in the FAS database, only 22 per cent were registered under the CRS at the gram panchayat in Warwat Khanderao. About 63 per cent of children were not registered at the gram panchayat in Warwat Khanderao, but were registered at other gram panchayats or local bodies outside Warwat Khanderao. Thus, the births of most children in the age-group 0–5 years in the FAS database were registered outside Warwat Khanderao. We found that almost all institutional births were recorded as demanded by the law. However, since there was no medical facility in Warwat Khanderao, mothers had to go to facilities located in the neighbouring town.

Conversely, the registers under CRS at the gram panchayat in Warwat Khanderao included 23 children whose births were registered in the village because their mothers, who were married to men resident in other villages, came temporarily to Warwat Khanderao for delivery. Thus the information from the CRS of a particular village cannot be used for the purpose of obtaining data on children needed for local-level administration, as it does not cover all children resident in the village.26

The micro-level picture of birth records at the village is somewhat different from a macro-level view based on the Sample Registration System (SRS) or the National Family Health Survey (International Institute for Population Sciences 2007). Although both the CRS and the SRS provide us with State-level macro data, we found difficulties in using the CRS data for the purpose of local-level administration. Certain systematic changes are required if the CRS data are to meet the increasing requirement and demand for decentralised databases not only for the purpose of local-level administration, but also for the purpose of micro-level planning of various development programmes.

Potential Use of ICDS Registers

We also examined the potential of the ICDS (Anganwadi) Child Registers in Warwat Khanderao. These registers should not have the problem of undercounting of children since all children, whether born in the village of residence (here Warwat Khanderao), or in the native village of their mothers, or at medical facilities located in a neighbouring town, are to be registered in the ICDS Child Register. In principle, the place of registration of the ICDS Child Register is the place of usual residence, whereas the place of registration of the CRS is the place of occurrence as mentioned above.

We also tried to match each child in the ICDS Child Register for the period 2005 to 2007 with children present in the FAS database for Warwat Khanderao. Out of 51 children identified in the FAS database as children born in the period 2005 to May 2007, 33 children (or 65 per cent) were recorded in the ICDS Child Register during and after the period 2005 to May 2007. Out of 50 children recorded in the ICDS Child Register for the period 2005 to May 2007, 29 children (or 58 per cent) were present in the FAS database. Therefore, although the ICDS Child Register may cover more children in the village than the CRS data, the quality of its data remains open to question and calls for further investigation.

Table 14 Discrepancies in the number of children recorded in the ICDS Register for the period 2005–07 and in the FAS database, Warwat Khanderao

| Database | FAS survey | ICDS Child Register | ||

| Matched | Not matched | Matched | Not matched | |

| FAS survey database | – | – | 33 (64.7%) | 18 (35.3%) |

| ICDS Child Register | 29 (58.0%) | 21 (42.0%) | – | – |

Sources: FAS village survey database; Child Register obtained from ICDS centre, Warwat Khanderao.

Note: Abbreviations are explained in the “Abbreviations and Glossary” section at the end of the article.

Further, we tried to match each child in the ICDS Child Register for the period January 2000 to June 2005 with children present in the FAS database in Bidyanidhi.27 We compared this list with the list of children aged 5 years and below from the FAS survey data. According to the ICDS Child Register, 59 children were born in the village between January 2000 and June 2005. According to the FAS survey data, the number of children in the age-group 0–5 years in June 2005 was 61. The names of 54 children were found in both the lists.

Table 15 Discrepancies in the number of children recorded in the ICDS Register for the period 2000–05 and in the FAS database, Bidyanidhi

| FAS survey | ICDS Child Register | |||

| Matched | Not matched | Matched | Not matched | |

| FAS survey database | – | – | 54 (88.5%) | 7 (11.5%) |

| ICDS Child Register | 54 (91.5%) | 5 (8.5%) | – | – |

Sources: FAS village survey database; Child Register obtained from ICDS centre, Bidyanidhi.

Note: Abbreviations are explained in the “Abbreviations and Glossary” section at the end of the article.

We looked into the discrepancy in detail, allowing for some divergences on account of temporary or permanent migrations, and misreported age during the FAS survey.28 From this analysis we were able to conclude that the coverage of the ICDS Child Register in Bidyanidhi is excellent.

The ICDS Child Registers, recorded in the place of usual residence, are intended to cover the births of all children resident in the village, so it is useful as a basis for village-level administration and planning. Under the post-73rd Amendment regime, therefore, the favoured data source with respect to village-level births has been shifting from a record such as the CRS to a record such as the ICDS Child Register, which is related directly to people resident in the gram panchayat.

Village Schedule on BSLLD

As stated earlier, the Expert Committee on BSLLD suggested a minimum list of variables on which data were to be collected at the village level by means of a Village Schedule.

In most cases, the details recorded in the Village Schedule are supposed to be supported by documentary evidence. With regard to villages in Raina gram panchayat, all the data items in the Village Schedule were certainly filled up. However, some of the data items in the Village Schedule were not likely to be available from village records. These included data items in:

Block-9: Land utilisation (in particular,

the number

of operational holdings by size and classes);

Block-12: Employment status;

Block-24: Migration;

Block-25: Other social indicators; and

Block-26: Industries and businesses (number of

small-scale enterprises and workers therein).

These were not documented in the village-level records and hence village functionaries had to rely on the personal assessment of a few knowledgeable persons without any validation check.

The Cross-Sectional Synthesis Report thus recommended that:

The Schedules (both Schedule A for periodic data and Schedule B for dynamic data) need to be rationalised with a view to reduce the incidence of missing data, particularly in respect of Schedule B items and to improve timeliness in the completion of field work for filling out the schedules. (Government of India 2011, p. vii)

This is an important matter for study and discussion.

As far as the data needs for micro-level annual (or five-year) planning and its implementation are concerned, dynamic changes from month to month are not a high-priority issue. While the Expert Committee on BSLLD initially recommended that Schedule B is to be collected only in the first month, its instructions for data recorders are ambiguous in this regard, treating the sub-Schedule as if it is to be filled in once every month. Reference months of the year need to be fixed for recording of data in Schedule B.29

Nevertheless, such month-by-month dynamic data are certainly required to serve the data needs of self-governance, for which certain routine entries must be made (and routine tasks specified) in order to monitor dynamic changes in the village community. But the nature of Data Needs III (data requirements for micro-level planning and its implementation) is different from that of Data Needs I (data requirements for self-governance) in this regard. All village-level data for self-governance need not travel upward for planning at various levels such as the block, district, State, etc.

The Village Schedule on BSLLD can be considered to cover subjects with respect to 29 functions listed in Schedule XI of the Constitution of India. However, the relationship between data items of the Village Schedule and each function listed in Schedule XI is not explicitly indicated by the Expert Committee on BSLLD.

Schedule XI provides a rough sketch of “subjects” of the 29 functions. However, the functions assigned to each tier of the PRI in respect of different subjects should be specific and unambiguous. For an analytical study of the relationship between data items in the Village Schedule and the functions listed in Schedule XI, we need a clear idea of specific operational and activity-related responsibilities. Without an idea of the concrete activities or schemes related to each subject of Schedule XI, it is difficult to discuss the use of data for micro-level planning and its implementation. Therefore, clear information on “Activity Mapping,” that is, a clear delineation of the functions of each level of the panchayat, is required in this regard.

Activity Mapping exercises in both the States under consideration are still in progress.30 The devolution of functions listed in the Bombay Village Panchayats Act, 1958 and Maharashtra Zilla Parishads and Panchayat Samitis Act, 1961 is still unclear. According to our interview at Warwat Khanderao, the situation on the ground is quite different from what is suggested by the statute books. In practice, the authority of Warwat Khanderao gram panchayat to carry out village-level schemes appears very limited.

In West Bengal, the progress of devolution by the departments was criticised by the State Finance Commission (Government of West Bengal 2009, p. 10) and executive orders with respect to Activity Mapping had not formally been published in the official gazette (Third State Finance Commission West Bengal 2008, pp. 21–22).

However, as the powers and authority given to PRIs are entirely at the discretion of State governments, and the provisions of the Article are recommendatory and not mandatory, there is yet no “model” Activity Mapping that has stood the test of application in diverse situations. The Task Force on Devolution of Powers and Functions to Panchayati Raj Institutions was constituted by the Ministry of Rural Development (MoRD) of the Government of India in 2001 to suggest guidelines for Activity Mapping as “a broad framework of devolution” (Government of India 2001, p. 15 and p. 47 ff.). We have tentatively used these guidelines as another criterion by which to assess the relationship between data items in the Village Schedule and each function listed in Schedule XI. That is to say, we used the Task Force’s guidelines with respect to Activity Mapping in addition to the existing scheme of Activity Mapping in each State to assess the relationship of data items of the Village Schedule with each of the functions listed in Schedule XI.