ARCHIVE

Vol. 1, No. 1

JANUARY-JUNE, 2011

Research Articles

Research Notes and Statistics

Symposium

Book Reviews

Agricultural Employment in a

Results from a Resurvey

R. Ramakumar* and Karankumar Raut†

*Associate Professor, School of Social Sciences, Tata Institute of Social Sciences, Mumbai.

†M. Phil. student, Tata Institute of Social Sciences, Mumbai.

Abstract: Vidarbha is a region in which, historically and in the contemporary period, the share of agricultural workers in the working population has been among the highest in the country. This paper discusses the ways in which changes in production conditions between the 1960s and 2000s in one western Vidarbha village – Dongargaon – influenced (a) the number of days of employment for agricultural labourers; (b) the levels of labour absorption in agriculture; and (c) the changes in the nature and extent of labour absorption in agriculture. Such a comparative study was facilitated by the availability of data and information from two surveys of the village: the first in 1963–64 by V. H. Joshi, and a resurvey in 2007 by a team led by the first author.

The paper argues that the aggregate number of days of employment gained by agricultural labourers in Dongargaon increased between 1963–64 and 2006–07. This argument is based on indirect evidence with respect to changes in labour absorption in the cultivation of different crops. However, the data and analysis presented in this paper show that, because of increases in the absolute number of agricultural workers and in the share of agricultural workers in the work force, increased labour absorption did not result in a proportionate rise in the number of days of employment available to an individual worker. In 2006–07, primary agricultural labourers in Dongargaon were employed only for about 111 days a year. Underemployment was thus a feature of the life of agricultural labourers. Lack of access to adequate non-agricultural employment, rising landlessness, and large-scale immigration of workers into the village undermined the potential gains of a rise in labour absorption.

Keywords: Vidarbha, village surveys, rural employment, labour absorption, migration.

This

paper deals with the employment status of agricultural labourers

in a village, Dongargaon, in the Vidarbha

region of Maharashtra. Specifically, it attempts to answer the following

questions. For how many days in a year, on average, did agricultural labourers in the village find employment? Did the number of

days of employment obtained by them differ across social groups, and between

men and women? To what extent did each of the different crops grown in the

village provide employment to the agricultural labourers?

What was the relative importance of agricultural and non-agricultural

employment in the employment profile of the labourers?

The

number of days of employment obtained by agricultural labourers

is affected by both “demand” and “supply” factors. Both historically and in the

contemporary period, Vidarbha has been known to be a

region with the highest share of India’s agricultural labourers.

Given the high incidence of agricultural labourers in

the region, this paper discusses the ways in which changes in production

conditions in the village under study influenced labour

absorption in agriculture between the 1960s and 2000s. In particular, it

analyses the ways in which the spread of irrigation, changes in cropping

pattern, and changes in techniques of production affected the number of days of

agricultural employment in the village during these decades.

The

primary data used in the paper are from a resurvey, conducted in 2007, of Dongargaon. The village was first surveyed in 1963–64;

information from the earlier survey is used here as a benchmark to compare and analyse the changes in labour

absorption in agriculture between then and 2007.

Days of Employment of Agricultural Labourers:

Sources of Data

The only available source of secondary data on

employment of agricultural labourers in India is the quinquennial

Employment and Unemployment surveys of the National Sample Survey Organization

(NSSO). Data on the number of days of employment of agricultural labourers are

extracted from the NSSO surveys and published separately as the Rural Labour Enquiry (RLE) by the Ministry of Labour,

Government of India.

This paper uses data on the category of usually occupied

workers belonging to rural labour households (RLHs)

from the presentation of results in the RLE

(see Table 1). In 2004–05, which is the last available round of the NSS, the

average number of days of wage employment for usually occupied workers in RLHs in Maharashtra was recorded as 225 days for men and

202 days for women. In other words, male workers were employed for 61 per cent

of the days in the year and female workers for 55 per cent of the days in the

year.

The RLE data

also show that workers from Scheduled Caste (SC) RLHs

in Maharashtra were employed for a marginally higher number of days in the year

2004–05. Male workers from SC RLHs were employed for

232 days and female workers from SC RLHs were

employed for 214 days.

Table 1 Average number of days of wage employment of usually occupied workers in agricultural labour belonging to RLHs, Maharashtra, RLE, 1977–78 to 2004–05, in number of full days

|

RLE round/year |

Average annual number of days of

employment for |

|||

|

Men |

Women |

|||

|

All workers |

SC workers |

All workers |

SC workers |

|

|

1977–78 |

250 |

232 |

198 |

202 |

|

1983 |

234 |

229 |

184 |

188 |

|

1987–88 |

247 |

256 |

145 |

119 |

|

1993–94 |

237 |

228 |

219 |

207 |

|

1999–2000 |

225 |

223 |

210 |

202 |

|

2004–05 |

225 |

232 |

202 |

214 |

Note: SC=Scheduled Caste; RLE=Rural Labour Enquiry; RLH=rural labour households.

Source: Bamezai (2010).

Scholars who work with primary data on Indian villages have for long questioned the reliability of the RLE data on the number of days of employment. They have argued that the average number of days of wage employment of agricultural labourers is considerably lower, in reality, than the RLE estimates. For instance, Ramachandran and Swaminathan (2004) note that:

… we do not have good enough macro-data on the number of days of employment, agricultural and non-agricultural, per worker per year in India. Not only do the data from the Rural Labour Enquiries appear intuitively to be incorrect … it is also well-recognized that employment data from micro studies show consistently lower volumes of employment than Rural Labour Enquiry data.

Mukherjee (1998; cited in Bamezai 2010) states that the differences between NSS/RLE data and village studies data can be

explained in terms of an inbuilt, upward bias in the collection and

classification of data by the NSS/RLE.

According to the methodology adopted by the NSS/RLE, an individual is considered to be “employed” for a full day if

s/he is engaged in gainful employment for four hours or more, and for half a day

if s/he is engaged in gainful employment for one hour or more. Such an approach

leads to classification (i) of a larger number of

individuals as gainfully “employed”; and (ii) of individuals engaged in low

income-generating “replacement activities”, for lack of gainful employment

opportunities, as gainfully “employed”. Mukherjee

further points out that most village studies record only the number of days of

gainful employment and hence a lower number of days of employment in a year.

In sum, RLE

data on the days of employment of agricultural labourers are inadequate to

understand the conditions of employment in rural India. Primary data from

village studies provide more meaningful estimates of the days of employment of

rural workers. Further, primary data help us to understand various

socio-economic characteristics of agricultural labour. For instance,

field-level data allow us to study the links between specific farming and

cropping patterns, on the one hand, and the number of days of employment of

labourers, on the other (which is not possible with secondary data).

The

Study Region and the Database

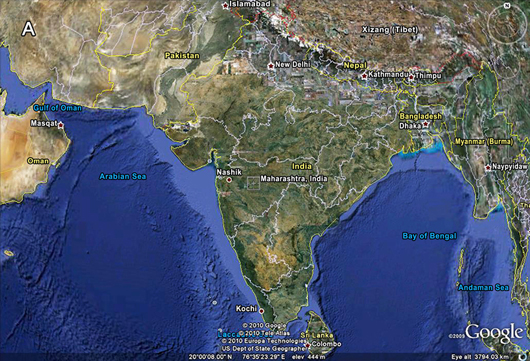

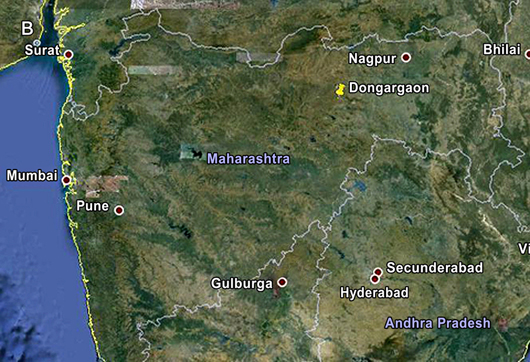

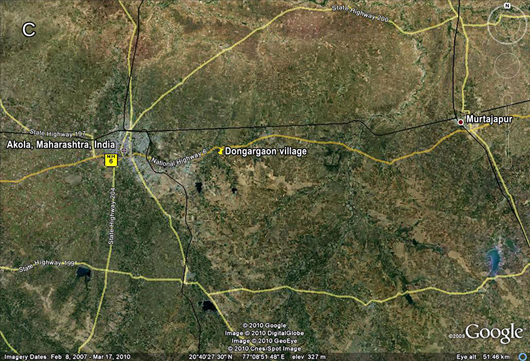

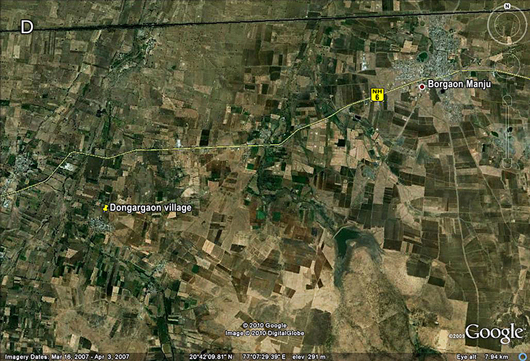

Dongargaon belongs to Akola tehsil

in Akola district, in the Vidarbha region of

Maharashtra (see Map Panel). The village is located at a distance of about 13 kilometres

from the town of Akola on the National Highway (NH) 6 that connects Akola to

Amravati and Nagpur. The village settlement (gaothan) is situated at less than

1 kilometre off NH 6, towards the south. The market-town of Murtizapur

is about 32 kilometres away from the village, to the east. Dongargaon

is surrounded by the villages of Sisa, Masa, Kumbhari, and Babulgaon, located at distances of between 3 to 5

kilometres.

Map Panel

(from top to bottom): Map of India showing Maharashtra State; Map

of Maharashtra showing Dongargaon in Akola district; Location of Dongargaon

between Akola and Murtizapur towns; A closer view of the location of

Dongargaon and the nearby Borgaon market

This paper is based on data collected from the village

of Dongargaon as part of a larger study of agrarian

relations in the villages of Maharashtra. Dongargaon

was surveyed by the study team of investigators in the summer of 2007, with

agricultural year 2006–07 as the reference year. At the time of the survey

there were 357 households in the village, and a census-type socio-economic

survey was conducted of all 357 households using detailed questionnaires (see

Table 2 for the demographic and agricultural details of the village). The survey began in the last week of April 2007 and was completed

by the third week of May the same year. An earlier survey of Dongargaon had been conducted in 1963, by V. H. Joshi of

the College of Agriculture, Akola (see Joshi 1967).

Table 2 Some basic demographic and agricultural details of Dongargaon, 2007 in number, acres and per cent

|

Item |

Number/ |

Share in total

population/ |

|

Total number of households |

357 |

- |

|

Total population |

1680 |

- |

|

Number of men |

855 |

51.0 |

|

Number of women |

825 |

49.2 |

|

Total number of SC households |

161 |

45.1 |

|

Total number of ST households |

45 |

12.6 |

|

Total number of VJNT households |

14 |

3.9 |

|

Population (>6 yrs) who are fully literate |

1202 |

80.3 |

|

Population (>6 yrs) who never went to school |

258 |

17.2 |

|

Average household size |

4.7 |

- |

|

Number of workers with primary occupation as: |

|

|

|

Agricultural labourer |

362 |

46.6 |

|

Cultivator |

246 |

31.7 |

|

Total area under ownership holdings (acres) |

668.3 |

- |

|

Extent of area irrigated |

270.5 |

40.5 |

|

Share of area owned by the top 5 per cent of households |

- |

46.0 |

Note: SC=Scheduled Caste; ST=Scheduled Tribe; VJNT=Vimuktya Jati and Nomadic Tribes.

Source: Survey data 2007.

There were five major caste groups among the

households of Dongargaon: Maratha, Mali, Chambhar, Navbaudh, and Gowari. Of these, the Navbaudhs (Dalit/SC) were the largest group, constituting 28.1 per

cent of the population. Malis (OBC or Other Backward Classes)

constituted 17.4 per cent, Chambhars (Dalit/SC) 13.8 per cent, and Marathas (Other Caste) 12 per

cent of the population. The share in population of Gowaris

(Adivasi/ST) was 8 per cent.

Dongargaon’s

Location in a Labour-surplus Region

Dongargaon is located in the Berar area of western Vidarbha, a region which, as mentioned earlier, has the highest incidence of agricultural labourers in India (see Reddy 1988).1 The growth of a large population of landless agricultural workers in Berar began during the cotton boom of the 1860s and continued well into the twentieth century. Using two different sources and estimates, Reddy (1988) shows that while in the 1860s, agricultural labourers in Berar accounted for between 14 to 33 per cent of the total work force, by the 1881 Census, the proportion of agricultural labourers had risen sharply, to about 50 per cent. In conclusion, he notes that:

... right through the regime of agrarian expansion beginning from the 1860s and ending in the 1920s, there were processes which created a substantial “demand” for agricultural labour in Berar, while market forces and colonial regulations maintained a high “supply’ of landless labour. (ibid., p. 202)

Even at the 2001 Census, more than 50 years after

India’s Independence, Berar claimed the largest share of India’s agricultural

labourers (see Ramakumar, Raut, and Kumar 2009),

showing that the supply of labour to Berar’s agrarian economy proceeded

unhindered over all these years. At the state level too, in 2001, the share of

agricultural labourers in the work force of Amravati division (which roughly

comprises Berar and includes Akola district), at 53.7 per cent, was the highest

in Maharashtra. Between 1961 and 2001, the share of agricultural labourers in

Amravati’s work force increased by 1.3 per cent, from 52.4 to 53.7 per cent.

Among the female work force the rise in share was higher: 65.4 per cent of the

female workers in Amravati division were agricultural labourers in 2001, as

opposed to 62.5 per cent in 1961. Among the Scheduled Caste (SC) workers of

Amravati, 72.6 per cent were agricultural labourers in 2001; and the share of

female SC agricultural labourers, at 82.1 per cent, was even higher.

In sum, it is clear that Berar is home to a large and

growing population of agricultural labourers, and that Dalits

constitute a significant share of the agricultural labour work force of the

region.

The village of Dongargaon shares the above characteristics with Berar (see Ramakumar, Raut, and Kumar 2009), as revealed by the following data. (i) Census of India data show that there was a dramatic increase in the share of workers employed as agricultural labourers in the village between 1961 and 2001, from 47.7 per cent to 71.1 per cent. (ii) During every inter-censal period between 1961 and 2001, except 1991–2001, the rate of increase in the number of agricultural labourers in the village was higher than the rate of increase of the population.2 In other words, there were major changes in the internal composition of the work force of Dongargaon between 1961 and 2001. (iii) A comparison of data from the 2007 survey with Joshi’s 1967 data shows that, between 1963–64 and 2006–07, Dongargaon registered a rise in the share of workers with agricultural labour as their primary occupation. (iv) The dependence on agricultural employment in the village was higher for female workers as compared to male workers. In 2006–07, agricultural labour was the primary occupation for 37.2 per cent of the male workers, while the corresponding share for female workers was 60.8 per cent (see Table 3 for details).

Table 3 Distribution of workers by primary occupation, by sex, Dongargaon, 2006–07 in numbers and per cent

|

Primary occupation |

Male

workers |

Female

workers |

All

workers |

|||

|

Number |

Share |

Number |

Share |

Number |

Share |

|

|

Agricultural labour |

174 |

37.2 |

188 |

60.8 |

362 |

46.6 |

|

Cultivation |

149 |

31.8 |

97 |

31.4 |

246 |

31.7 |

|

Self-employed |

36 |

7.7 |

14 |

4.5 |

50 |

6.4 |

|

Non-agricultural manual work |

51 |

10.9 |

3 |

1.0 |

54 |

6.9 |

|

Non-agricultural non-manual work |

35 |

7.5 |

4 |

1.3 |

39 |

5.0 |

|

Salaried work |

22 |

4.7 |

3 |

1.0 |

25 |

3.2 |

|

Allied activities in agriculture |

1 |

0.2 |

0 |

0.0 |

1 |

0.1 |

|

Total |

468 |

100.0 |

309 |

100.0 |

777 |

100.0 |

Source: Survey data 2007.

The 2007

survey data reveal an extremely unequal pattern of land ownership in Dongargaon. Landlessness in the village increased sharply

between 1963 and 2007, with the share of landless households rising from 27.7

per cent to 63.6 per cent. Marathas and Kunbis were

seen to be the most dominant landowners in 2007, with 48 per cent of the total

land-holdings in their possession although they constituted only 18.1 per cent

of the population. In contrast, members of the Navbaudh

religious community, who accounted for 28.1 per cent of the population, owned

only 10.2 per cent of the land.

The

sharp rise in landlessness in Dongargaon between 1963

and 2007, as we have argued elsewhere (Ramakumar, Raut, and Kumar 2009), was due to two main

factors. First, the rise in demand for labour

generated by the spread and intensification of cotton cultivation, over a

period, attracted a substantial number of landless Dalit,

Adivasi and VJNT (Vimuktya Jati and Nomadic Tribe) labourers

from outside the village. It is also possible that migration into Dongargaon, and into Akola as a whole, was driven by the

severe and recurrent droughts that affected large parts of Maharashtra in the

early 1970s.

However,

distress migration alone does not explain the significant increase in the Dalit population of the village between the 1960s and 2000s

(ibid.). Among the Dalit households of Dongargaon,

there was a practice of sons-in-law being brought to the village after marriage

and of newly married couples being settled there, rather than daughters being

sent to their marital homes/villages. Dalit men who

married from Dongargaon did not, on the other hand,

move out to their brides’ villages. In interviews with Dalit

elders of the village during the 2007 survey, this was repeatedly and

consistently pointed out as a major reason for the increase in the Dalit population. The readiness with which sons-in-law

moved to Dongargaon was related to the rise in

employment opportunities in and around the village.

The

second important reason for the sharp rise in landlessness in Dongargaon was the increase in the purchase of village land

by persons from outside, due to the spread of cotton cultivation, and due to

the proximity of the village to the National Highway and the MIDC (Maharashtra

Industrial Development Corporation) in Babhulgaon.

This led to a net loss of land-holdings among inhabitants of the village (ibid.).

In terms of employment opportunities in agriculture,

the expansion in the supply of labour in the village has been a major

depressing factor (for historical evidence of this

in

This paper attempts to understand the changes in the

employment available to agricultural labourers in Dongargaon

in the context of these changes in the pattern of labour absorption. Given the

increase in labour supply over the years, what role has been played by the rise

in demand for labour in determining the number of days of employment available

to agricultural labourers? More importantly, are there limits to such an

expansion of employment?

The

Agricultural Work Calendar in Dongargaon

Employment

opportunities in the cultivation of kharif crops in Dongargaon arise in the month of April, when the clearing

and ploughing operations begin (Table 4). Ploughing continues till about the middle of June and then,

once the rains arrive, the sowing operations begin. Thus the peak employment

season for male labourers begins in April and the

peak season for female labourers begins later, in

June. July and August are the months for weeding and fertilizer application.

Cotton-picking and the harvesting of sorghum (jowar) and pulses begin in the month of September and continue till

November. Extension of the kharif harvest season till

November has been due to the introduction of Bt cotton varieties, which involve

a larger number of rounds of picking. Much of the employment generated between

September and November is for female labourers.

From

October onwards, as and when harvesting is completed, shallow ploughing and sowing of the second crop begin in irrigated

plots. All sowings are completed by November. The months of December and

January are set aside for weeding, irrigation, and fertilizer/pesticide

application in the cultivation of wheat, red gram (tur), and vegetables. While wheat and vegetables are harvested in the

month of February, red gram is harvested a little later, in March.

Table 4 Calendar of operations for major crops, by months, Dongargaon, 2006–07

|

Month |

Operations |

Major crops grown |

|

April |

Deep ploughing, shallow

ploughing, clearing the land |

Cotton, sorghum, pulses,

soyabean |

|

May |

Deep ploughing, shallow

ploughing, clearing the land |

Cotton, sorghum, pulses, soyabean |

|

June |

Shallow ploughing, sowing,

fertilizer application, |

Cotton, sorghum, pulses,

soyabean |

|

July |

Hand weeding, animal weeding, fertilizer application |

Cotton, sorghum, pulses, soyabean |

|

August |

Hand weeding, animal weeding, pesticide application |

Cotton, sorghum, pulses, soyabean |

|

September |

Harvesting/picking, threshing |

Cotton, sorghum, pulses, soyabean |

|

October |

Harvesting/picking, threshing (kharif) |

Cotton, sorghum, pulses, soyabean |

|

November |

Harvesting/picking, threshing (kharif) shallow |

Cotton, sorghum, pulses, soyabean |

|

December |

Hand weeding, irrigation, fertilizer application |

Wheat, red gram, vegetables |

|

January |

Hand weeding, irrigation, fertilizer application, |

Wheat, red gram, vegetables |

|

February |

Harvesting, threshing |

Wheat, vegetables |

|

March |

Harvesting, threshing |

Red gram |

Source: Notes taken during the 2007 survey of the village.

Number

of Days of Employment in Agriculture

Classification

of the Working Population

Based on

the 2007 survey, the working population of Dongargaon

may be divided into four broad groups:

(i) workers who are primarily employed as agricultural labourers;

(ii) workers who are primarily employed in non-agricultural manual work

and whose secondary occupation is agricultural labour;

(iii) workers for whom cultivation is the primary occupation and

agricultural labour a secondary occupation;

(iv) workers who are exclusively employed in the non-agricultural

sector.

In the

discussion here of the number of days of employment in agriculture, only the

first three groups of workers are considered for analysis.

Number

of Days of Employment

There

were 317 primary agricultural labourers (group i) in the village in 2007, and their average number of days

of employment in 2006–07 was 111 (Table 5). Thus primary agricultural labourers in Dongargaon were

employed for just about four months a year, on average. This group of labourers was almost completely dependent on agricultural

work, with as much as 94 per cent of their days of employment coming from

agriculture and only 6 per cent from outside agriculture. Agriculture provided

an average of 104 days of employment to a primary agricultural labourer. In other words, the access to non-agricultural

employment for primary agricultural labourers taken

as a whole was limited.

The

difference between male and female primary agricultural workers in terms of the

number of days of employment was marginal. In 2006–07, men were employed for an

average of 118 days and women for an average of 105 days. This difference in

the average number of days of employment between males and females was

accounted for by the days of non-agricultural employment obtained by male

workers. If men obtained an average of 12 days of work in a year in the

non-agricultural sector, the corresponding number of days of such work for

women was only 2. On the other hand, within agriculture, the difference in the

number of days of employment between men and women was small: in 2006–07, men

obtained 106 days and women obtained 103 days of agricultural work.

Table 5 Number of days of employment, primary and secondary agricultural workers, by sector, Dongargaon, 2006–07 in days per year

|

Category |

Agriculture |

Non-agriculture |

Total |

|||

|

Days |

Share (%) |

Days |

Share (%) |

Days |

Share (%) |

|

|

(a) Primary agricultural

labourers (N=317): |

||||||

|

Men |

106 |

89.8 |

12 |

10.2 |

118 |

100.0 |

|

Women |

103 |

98.1 |

2 |

1.9 |

105 |

100.0 |

|

All persons |

104 |

93.7 |

7 |

6.3 |

111 |

100.0 |

|

(b) Secondary agricultural

labourers with daily non-agricultural |

||||||

|

Men |

69 |

39.7 |

105 |

60.3 |

174 |

100.0 |

|

Women |

55 |

47.0 |

62 |

53.0 |

117 |

100.0 |

|

All persons |

65 |

41.1 |

93 |

58.9 |

158 |

100.0 |

|

(c) Secondary agricultural

labourers with cultivation as |

||||||

|

Men |

70 |

85.4 |

12 |

14.6 |

82 |

100.0 |

|

Women |

102 |

100.0 |

0 |

0.0 |

102 |

100.0 |

|

All persons |

83 |

92.2 |

7 |

7.8 |

90 |

100.0 |

Source: Survey data 2007.

For

secondary agricultural labourers with

non-agricultural manual work as their primary occupation (group ii), who were

63 in number in 2006–07, the average number of days of employment in a year was

higher than for primary agricultural labourers, at

158 days. This group of workers was engaged in agriculture for only 41 per cent

of their total number of days of employment; the larger share of their days of

employment (59 per cent or 93 days) came from the non-agricultural sector.3 It was

seen that male labourers in this group obtained a

significantly larger number of days of employment than female labourers; on average, the number of days of employment for

men was 174 days and for women, 117 days. As was the case with the first group,

namely primary agricultural labourers, there was not

much of a difference between men and women in this group in terms of the number

of days of agricultural employment. However, the annual number of days of

non-agricultural employment was significantly higher for men (105 days) as

compared to women (62 days).

For the

third group of workers, those with cultivation as primary occupation and

agricultural labour as secondary occupation, the

average number of days of employment in a year, at 90 days, was the lowest. One

reason for this low figure could be the fact that while the survey collected

worker-wise data for agricultural wage

labour, it did not collect worker-wise data for

family labour in agriculture. The survey data record

only the total number of family labour days, sex-wise, for each operation in each crop. As

a result, the number of days spent on the family farm was not considered while

calculating the total number of days of employment for workers whose primary

occupation was cultivation and secondary occupation was agricultural labour. Yet, what is notable is that for women belonging to

this group of workers, the number of days of employment in agriculture (102

days) was almost the same as for women in the first group of primary

agricultural labourers. The 39 female workers in this

third group put in only a limited number of days of work on the family farm. On

the other hand, male workers in the third group were more involved in family labour than in hired labour;

therefore, in 2006–07, the number of days of employment in agriculture for men

(70 days) was considerably lower than that for women (102 days) in this group.

As noted

above, the average number of days of

agricultural employment for primary agricultural labourers

(group i) in 2006–07 was 106 days for men and 103

days for women. However, roughly half of these male and female agricultural labourers obtained less than 100 days of employment (see

Table 6) during the year, with 49.3 per cent of the men working for less than

100 days and 53.3 per cent of the women working for less than 100 days.

Further, roughly a third of this group of workers – 32.3 per cent of men and

34.5 per cent of women – worked for less than 75 days a year. This goes to show

that underemployment was an important feature of the work profile of

agricultural labourers in Dongargaon

in 2006–07. Lack of access to adequate non-agricultural employment and

in-migration to the village were factors that contributed to the

underemployment.

Table 6 Distribution of workers by size-classes of number of days of employment in agriculture, primary agricultural labourers, Dongargaon, 2006–07 in number and per cent

|

Size-classes of days |

Men |

Women |

||

|

Number |

Share |

Number |

Share |

|

|

Less than 50 |

20 |

13.2 |

20 |

12.1 |

|

50 to 75 |

29 |

19.1 |

37 |

22.4 |

|

75 to 100 |

26 |

17.1 |

31 |

18.8 |

|

100 to 125 |

24 |

15.8 |

23 |

13.9 |

|

125 to 150 |

16 |

10.5 |

25 |

15.2 |

|

150 to 175 |

21 |

13.8 |

15 |

9.1 |

|

175 to 200 |

9 |

5.9 |

6 |

3.6 |

|

More than 200 |

7 |

4.6 |

8 |

4.8 |

|

Total |

152 |

100.0 |

165 |

100.0 |

Source: Survey data 2007.

Number

of Days of Employment by Caste Group

Differences

across caste groups in the average annual number of days of employment, ranging

between 101 and 120 days (Table 7), were not large among male primary agricultural labourers. Dalit male labourers obtained the

largest number of days of employment, at 120 days, followed by OBC males at 118

days and Adivasi males at 116 days. On the other

hand, the number of days of employment for female

agricultural labourers registered wider differences

across caste groups. Adivasi women had the largest

number of days of employment, at 114 days, followed by Dalit

women at 107 days. Women from the VJNT and OBC categories had fewer days of

employment in 2006–07 than Dalit and Adivasi women.

Table 7 Number of days of employment, primary and secondary agricultural workers, by caste and sector, Dongargaon, 2006-07 in days per year

|

Category |

Agriculture |

Non-agriculture |

Total |

|||

|

Men |

Women |

Men |

Women |

Men |

Women |

|

|

(a) Primary agricultural labourers (N=317): |

||||||

|

General (5) |

88 |

55 |

13 |

0 |

101 |

55 |

|

OBC (72) |

108 |

94 |

10 |

0 |

118 |

94 |

|

Dalits (172) |

103 |

104 |

17 |

3 |

120 |

107 |

|

Adivasis (59) |

110 |

112 |

6 |

2 |

116 |

114 |

|

VJNT (9) |

109 |

84 |

0 |

7 |

109 |

91 |

|

All workers (317) |

106 |

103 |

12 |

2 |

118 |

105 |

|

(b) Secondary agricultural labourers with daily

non-agricultural |

||||||

|

General (6) |

66 |

10 |

128 |

0 |

194 |

10 |

|

OBC (10) |

70 |

50 |

40 |

0 |

110 |

50 |

|

Dalits (24) |

51 |

63 |

152 |

30 |

203 |

93 |

|

Adivasis (4) |

72 |

60 |

60 |

125 |

132 |

185 |

|

VJNT (19) |

96 |

70 |

64 |

137 |

160 |

207 |

|

All workers (63) |

69 |

55 |

105 |

62 |

174 |

117 |

Source: Survey data 2007.

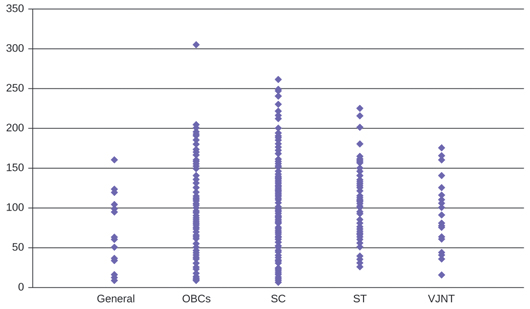

The data

relating to primary agricultural labourers contained

in Table 7 are presented in a different format in Figure 1. Here, the plotting

is in terms of the number of days of employment for agricultural labourers by caste group. The figure shows that a

significant proportion of labourers from all caste

groups obtained less than 100 days of employment in 2006–07. Of the major caste

groups, only among Dalits and Adivasis

did more than 50 per cent of the primary agricultural labourers

obtain more than 100 days of employment.

For secondary agricultural labourers from all the caste groups, except for OBCs whose access to non-agricultural employment was relatively limited, the number of days of employment was higher than for primary agricultural labourers (Table 7). Male Dalit secondary agricultural labourers recorded the highest average number of days of employment, 203 days, in 2006–07. Male Dalit labourers also obtained the highest number of days of non-agricultural employment as compared to the other caste groups.4

Scatter plot of the number of days of employment in agriculture, primary agricultural labourers, by caste group, Dongargaon, 2006-07 in number

Source: Survey data 2007.

The

women among secondary agricultural labourers worked

in agriculture only during the peak season of cotton/sorghum sowing, cotton

picking, and wheat harvesting, which accounted for roughly two months in the

year. Among them, the VJNT caste group recorded the largest number of days of

employment, 207 days, in 2006–07. For both men and women belonging to the VJNT

group, selling pieces of cutlery in nearby villages was an important form of

non-agricultural employment. The relatively high number of days of

non-agricultural employment among VJNT women reflected this occupational

pattern.

Number

of Days of Employment Across Crops

As noted

earlier, while cotton, sorghum, and wheat were the most important mono-crops

grown in the village, a large area of land was also devoted to inter-crops of

cotton, sorghum, and pulses. During the 2007 survey, it was seen that

agricultural labourers often found it difficult to

precisely identify the crops that were, or would be, grown on the plots on

which they worked. For instance, male agricultural labourers

did not always know if the field they had ploughed would be planted with a mono-crop

or an inter-crop. Even when they knew, the large number of days of employment

provided by cotton, sorghum, pulses, and their inter-crops made it difficult for

them to report the exact number of working days for each of these. This paper

presents crop-wise data on employment wherever available, and aggregates the

rest under inter-crops.

Taken

together, cotton, sorghum, pulses, and their inter-crops accounted for 91 per

cent of the total number of days of employment for men and 88 per cent of days

of employment for women in Dongargaon, in 2006–07

(Table 8). Inter-crops of cotton, sorghum, and pulses provided about half the

average number of days of employment for men and one-third the average number

of days of employment for women. The lower number of days recorded for women

under inter-cropping was due to the fact that they were able to identify the

crops on which they worked more easily. Women were largely occupied in the

sowing and harvesting of specific crops, which they could therefore identify,

as against tasks like ploughing and weeding that were

common across plots. Thus it was seen that about 42 per cent of the average

number of days of employment of female agricultural labourers

were devoted to tasks in cotton cultivation.

Table 8 Average number of days of employment, primary agricultural labourers, by crop, Dongargaon, 2001 in days per year and per cent

|

Crop |

Men |

Women |

||

|

Number of |

Share of |

Number of |

Share of |

|

|

Cotton |

26 |

24.9 |

43 |

41.9 |

|

Sorghum |

17 |

16.1 |

13 |

12.2 |

|

Red gram, black gram |

2 |

1.6 |

3 |

2.5 |

|

Inter-crops: cotton, sorghum, and pulses

|

53 |

49.8 |

35 |

33.5 |

|

Soyabean |

3 |

2.6 |

1 |

1.2 |

|

Wheat |

4 |

4.0 |

1 |

1.3 |

|

Vegetables |

1 |

0.7 |

7 |

6.4 |

|

Other crops |

0 |

0.4 |

1 |

0.9 |

|

All crops |

106 |

100.0 |

103 |

100.0 |

Note: The figures for each crop are normalized to reflect proportions in the overall average.

Source: Survey data 2007.

Cultivation

of crops like wheat and soyabean did not account for

a significant share of the number of days of employment of primary agricultural

labourers (Table 8). This was partly due to the lower

shares of these crops in the gross cropped area, and partly because of the

lower labour absorption in these crops as compared to

crops like cotton.

In Table 9, disaggregated figures are presented for the employment of agricultural labourers in cotton, sorghum, pulses, and their inter-crops

(which together provided 91 per cent of all employment). It will be seen that

the average number of days of employment here (102 for men and 94 for women)

are different from the figures given in Table 5; this is because these averages

are only for cotton, sorghum, pulses, and their inter-crops, and not for all

crops.

Table 9 Number of days of employment obtained in plots in which cotton, sorghum, pulses, and other crops are inter-cropped, primary agricultural labourers, by operation, Dongargaon, 2006–07 in days per year

|

Operation |

Male workers |

Female workers |

||

|

Days |

Share (%) |

Days |

Share (%) |

|

|

Clearing the land |

2 |

2.0 |

5 |

5.3 |

|

Deep ploughing |

15 |

14.7 |

0 |

0.0 |

|

Shallow ploughing |

16 |

15.7 |

0 |

0.0 |

|

Sowing |

8 |

7.8 |

8 |

8.5 |

|

Manure application |

0 |

0.0 |

0 |

0.0 |

|

Fertilizer application |

3 |

2.9 |

6 |

6.4 |

|

Pesticide application |

1 |

1.0 |

0 |

0.0 |

|

Animal weeding |

17 |

16.7 |

0 |

0.0 |

|

Hand weeding |

18 |

17.6 |

35 |

37.2 |

|

Irrigation |

1 |

1.0 |

0 |

0.0 |

|

Harvesting: cotton |

6 |

5.9 |

28 |

29.8 |

|

Harvesting: sorghum |

13 |

12.7 |

9 |

9.6 |

|

Harvesting: red gram |

1 |

1.0 |

0 |

0.0 |

|

Harvesting: other crops |

1 |

1.0 |

3 |

3.2 |

|

All operations |

102 |

100.0 |

94 |

100.0 |

Source: Survey data 2007.

For male

agricultural labourers, deep and shallow ploughing accounted for about 31 per cent, and animal and

hand weeding for about 34 per cent of the average annual number of days of

agricultural employment. Apart from these, the only other agricultural task

that provided substantial employment to male agricultural labourers

was harvesting in sorghum cultivation. Taken together, ploughing,

weeding, and sorghum harvesting accounted for about 77 per cent of their

average number of days of employment.

For

female agricultural labourers, about 67 per cent of

the average number of days of employment came from hand weeding and cotton

picking. Harvesting in sorghum provided 9.6 per cent of the days of employment,

and sowing provided another 8.5 per cent. In other words, the tasks providing

employment to women were less diverse than those for men.

Demand Factors Associated

with Changes in Days of Employment

Since

the study by Joshi (1967) does not provide estimates of the number of days of employment of Dongargaon’s agricultural labourers

in 1964, it has not been possible to quantify the changes in the number of days

of employment in the village between 1963–64 and 2006–07. What Joshi’s study

does provide, however, are estimates of labour

absorption per acre for each crop, as well as an account of the methods of

production in each crop, in 1963–64. Information is also available on the

changes in the larger agrarian economy of Dongargaon

between the 1960s and 2000s.

Based on

the available information, it may be surmised that the average annual number of

days of employment of agricultural labourers in Dongargaon has increased between 1963–64 and 2006–07, due

to the following reasons. First, there has been a spread of irrigation in the

village, which has led to a larger number of crops being grown as well as more

intensive cultivation within each crop. Secondly, changes in the cropping

pattern have been in favour of crops that are more labour-absorbing. Thirdly, changes in the methods of

production have raised the net levels of labour

absorption, especially of women workers. It should be noted, though, that in

spite of the general increase in labour absorption,

the average number of days of employment for agricultural labourers

has not increased beyond four months a year. It would appear that the rise in

the “supply” of labour has stymied increased

availability of employment in the village.

Changes

in Irrigation and Labour Use

In 1963–64,

Dongargaon was primarily a rainfed

village. Only about 16 acres of land, accounting for 3.1 per cent of the net

cropped area, were irrigated (Joshi 1967). As Joshi wrote:

The area is principally a kharif tract. More than ninety per cent of the gross cropped area is under kharif crops. The principal kharif crops are cotton, sorghum, ground nut and red gram. The principal rabi crops are wheat and vegetables. Cotton and sorghum, between themselves, account for about three-fourths of the area. (Ibid., p. 80.)

About 96

per cent of the gross cropped area in Dongargaon was

first-season land in 1963–64 (Table 10), of which 55.2 per cent was cultivated

with sorghum and 33.8 per cent with cotton; sorghum and cotton together accounted

for 89 per cent of the gross cropped area. In the second season, vegetables,

mainly brinjal and onion, were cultivated. According

to Joshi:

The main reason for the infrequency of the rabi crop is on account of the complete absence of irrigation facilities. Whatever irrigation is there is from wells, and naturally, this costly irrigation facility is used for more paying crops like vegetables, fruit crops or sugarcane. (Ibid., p. 80; emphasis added.)

Table 10 Cropping pattern in Dongargaon, 1963 in acres and per cent

|

Crop |

Cultivated

area |

Share

in gross |

Share

of area |

|

1. Kharif and dry crops: |

|||

|

Sorghum |

264.50 |

53.42 |

55.15 |

|

Bajra |

0.25 |

0.05 |

0.05 |

|

Red

gram |

7.87 |

1.59 |

1.64 |

|

Black

gram |

2.20 |

0.44 |

0.46 |

|

Green

gram |

7.12 |

1.44 |

1.48 |

|

Other

pulses |

0.10 |

0.02 |

0.02 |

|

Cotton |

162.05 |

32.73 |

33.79 |

|

Groundnut |

35.50 |

7.17 |

7.40 |

|

All kharif crops |

479.59 |

96.87 |

100.00 |

|

2. Rabi and irrigated crops: |

|||

|

Chilli |

0.21 |

0.04 |

1.38 |

|

Banana |

1.00 |

0.20 |

6.55 |

|

Brinjal |

7.00 |

1.41 |

45.84 |

|

Onion |

3.20 |

0.65 |

20.96 |

|

Other

vegetables |

1.66 |

0.34 |

10.87 |

|

Sugarcane |

1.20 |

0.24 |

7.86 |

|

Wheat |

1.00 |

0.20 |

6.55 |

|

All rabi crops |

15.27 |

3.08 |

100.00 |

|

Gross cropped area |

495.11 |

100.00 |

- |

Source: Joshi (1967).

Crop

rotation (the successive cultivation of different crops in a specified sequence

on the same field) was commonly practised in Dongargaon in 1963. According to Joshi (1967), the most important crops cultivated

in this manner were cotton and sorghum, in cycles of one- or two-year rotation.

In other words, cotton and sorghum were cultivated in turn either every

alternate year, or every two years. On some plots of land, crop rotation

between sorghum and groundnut was also seen.

By 2007,

agriculture in Dongargaon had undergone a total

transformation. The expansion of irrigation, along with technical advances and

the growth of markets, had led to major changes in the types of crops grown,

the number of crops grown each year, and the nature of inter-cropping. The

village was no longer dry and predominantly kharif,

as it was in 1963–64. In 2006–07, of the 534 acres of land owned by inhabitants

of the village, 179 acres (or 33.5 per cent) were irrigated. If only the area

of cultivated land (excluding land left fallow that year) is considered, the

share of irrigated land increases to 40.5 per cent. Expansion of irrigation had

a major impact on the availability of employment in agriculture in Dongargaon, as shown below.

Changes

in Cropping Pattern and Labour Use

Between 1963 and 2007 the cropping

pattern in the village witnessed major changes (see Table 11), although the

major crops continued to be sorghum and cotton in the first season, and wheat

and vegetables in the second season. First, the area under cotton in 2007 was

significantly larger than in 1963, and it exceeded the area under sorghum by a

large margin. Secondly, along with traditional and hybrid varieties of cotton,

Bt cotton was also widely cultivated. Bt cotton was primarily grown as a mono-crop,

though it was sometimes inter-cropped with sorghum and red gram. Thirdly, soyabean had emerged as an important crop cultivated in the

first season. Fourthly, there was a significant growth in the land area devoted

to second-season crops, the most important of which was wheat, followed by

vegetables. In terms of the area under cultivation, wheat had become the third

most important crop in the village. Fifthly, there was a major increase in the

variety of vegetables grown in the second season, alongside a rise in the total

land area under vegetables.

An

important feature of the cropping pattern in Dongargaon

in 2007 was the wide variety of inter-crops. The survey noted the existence of

about 45 different combinations of crops (mono-crops and inter-crops taken together).

A summary of the area under each of these crop combinations is given in Table 11. Mono-cropping of cotton accounted for the single largest share of gross

cropped area, with 32.3 per cent of the cultivated land devoted to solely

cotton/Bt cotton. Cotton was also cultivated as an inter-crop, along with red

gram, sorghum, soyabean, and black gram, in an

additional 9.1 per cent of the gross cropped area. Thus cotton cultivation

accounted for a total of about 41 per cent of the gross cropped area. Sorghum

was the second most important mono-crop, cultivated in 21.7 per cent of the

gross cropped area. It was also cultivated as an inter-crop with red gram,

black gram and green gram, taking the total area under sorghum cultivation up

to about 27 per cent of gross cropped area. Wheat in the second season and soyabean in the first season were the third and fourth most

important mono-crops, in that order.

Table 11 Area under different crops and gross cropped area, Dongargaon, 2006–07 in acres and per cent

|

Crop combinations |

Irrigated area |

Unirrigated area |

Gross cropped area |

|||

|

Area |

Share in |

Area |

Share in |

Area |

Share in |

|

|

Cotton |

30.5 |

11.3 |

156.3 |

39.3 |

186.8 |

27.9 |

|

Bt cotton |

24.0 |

8.9 |

5.0 |

1.3 |

29.0 |

4.3 |

|

Sorghum |

43.5 |

16.1 |

101.3 |

25.4 |

144.8 |

21.7 |

|

Wheat |

99.8 |

36.9 |

4.0 |

1.0 |

103.8 |

15.5 |

|

Cotton + red

gram |

0.0 |

0.0 |

25.0 |

6.3 |

25.0 |

3.7 |

|

Cotton + sorghum

+ red gram |

3.0 |

1.1 |

6.0 |

1.5 |

9.0 |

1.3 |

|

Cotton + red

gram + soyabean |

3.5 |

1.3 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

3.5 |

0.5 |

|

Cotton + black

gram |

0.0 |

0.0 |

3.0 |

0.8 |

3.0 |

0.4 |

|

Bt cotton

+ red gram |

0.0 |

0.0 |

12.0 |

3.0 |

12.0 |

1.8 |

|

Bt cotton

+ sorghum |

4.0 |

1.5 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

4.0 |

0.6 |

|

Cotton + sorghum |

0.0 |

0.0 |

4.0 |

1.0 |

4.0 |

0.6 |

|

Sorghum +

red gram |

1.5 |

0.6 |

9.0 |

2.3 |

10.5 |

1.6 |

|

Sorghum +

black gram |

5.3 |

2.0 |

2.0 |

0.5 |

7.3 |

1.1 |

|

Soyabean |

9.0 |

3.3 |

30.0 |

7.5 |

39.0 |

5.8 |

|

Red gram |

8.5 |

3.1 |

16.1 |

4.1 |

24.6 |

3.7 |

|

Red gram

+ soyabean |

3.6 |

1.3 |

8.0 |

2.0 |

11.6 |

1.7 |

|

Red gram

+ black gram |

0.0 |

0.0 |

4.0 |

1.0 |

4.0 |

0.6 |

|

Black

gram |

2.5 |

0.9 |

5.0 |

1.3 |

7.5 |

1.1 |

|

Green

gram |

1.5 |

0.6 |

2.5 |

0.6 |

4.0 |

0.6 |

|

Cabbage |

3.3 |

1.2 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

3.3 |

0.5 |

|

Others,

including vegetables |

27.1 |

10.0 |

4.8 |

1.2 |

31.8 |

4.8 |

|

Total |

270.5 |

100.0 |

397.9 |

100.0 |

668.3 |

100.0 |

Note: “Cotton” refers to the traditional variety of cotton.

Source: Survey data 2007.

The

changes seen from 1963 to 2007 in the type and combination of crops cultivated

in the village were brought about and deeply influenced by the availability of

irrigation. For instance, by 2007, about 37 per cent of the gross irrigated

cropped area was cultivated with wheat, which was exclusively a second-season

crop. The expansion of wheat cultivation in the second season can be attributed

exclusively to the spread of irrigation. Increased vegetable cultivation in the

second season was also a result of the spread of irrigation; vegetables

occupied 11.2 per cent of the gross irrigated cropped area, as against only 1.2

per cent of the gross non-irrigated cropped area (see Table 11). Annual

cultivation of a larger number of crops was a major feature of the change in

the production environment, which in turn had an effect on the number of days

of employment available to labourers.

Another

important change in cropping pattern brought about by the spread of irrigation

was the opening up of the possibility of cultivating Bt cotton. The higher

yield of Bt cotton, as compared to traditional varieties of cotton, hinged on

the availability of water; the risks were high in cultivating Bt cotton on

non-irrigated land. In 2006–07, about 10.4 per cent of the gross irrigated

cropped area was under Bt cotton, as compared to about 4.3 per cent of the

gross non-irrigated cropped area; in the non-irrigated plots, Bt cotton was

largely inter-cropped with red gram. The spread of Bt cotton, as noted later in

this paper, also led to major changes in labour use

in cotton cultivation.

Changes

in Labour Absorption across Crops

Labour Use in Cotton (Traditional and Hybrid)

Joshi’s study (1967) documents the average annual labour absorption (including hired and family labour) in cotton and sorghum for the year 1963–64.5 The total labour use in sorghum was estimated to be 24 days per acre, and in cotton, 34 days per acre (Table 12). In sorghum, the number of male labour days was higher than the number of female labour days. In cotton, the number of male and female labour days used were almost equal.

Table 12 Labour absorption in different crops, Dongargaon, 1963–64, in number of 8-hour days per acre

|

Operation |

Sorghum |

Cotton |

||

|

Men |

Women |

Men |

Women |

|

|

Preparatory tillage |

5.0 |

2.0 |

8.0 |

2.0 |

|

Sowing |

2.0 |

0.5 |

2.0 |

1.0 |

|

Manuring |

1.0 |

0.5 |

1.0 |

1.0 |

|

Weeding |

2.5 |

3.0 |

6.0 |

11.0 |

|

Harvesting and threshing |

4.0 |

3.5 |

0.5 |

1.5 |

|

Total |

14.5 |

9.5 |

17.5 |

16.5 |

Source: Survey data 2007.

Based on

the 2007 survey data, separate estimates are given here of the number of labour days in 2006–07 for non-Bt cotton, Bt cotton,

sorghum, and a set of typical inter-crops including cotton, sorghum, red gram,

and wheat. The estimates of labour use in non-Bt

cotton, Bt cotton, and sorghum are from plots of land where they were grown as mono-crops.

For each of these crops/crop combinations, separate estimates are also given,

wherever possible, for plots that used machines and plots that used human labour in every operation. Further, the range of labour days used by irrigated and unirrigated

plots for each operation is also presented. Data on family labour

by sex and by operation were collected for all the crops. All the estimates

presented include both hired labour days and family labour days.

Between 1963–64 and 2006–07, the number of labour days used per acre in Dongargaon increased for both cotton and sorghum. On 1 acre of land under cotton, the average number of labour days used in 2006–07, under different conditions, was as follows (see Table 13). Where operations were mechanized with the use of tractors, the number of labour days for unirrigated plots was 57 and for irrigated plots, 99. Where only human/manual labour was used, the number of labour days for unirrigated plots was 61 and for irrigated plots, 103. A common feature in all instances was that the number of female labour days exceeded the number of male labour days by a considerable margin. The division of labour between men and women was clearly laid out: male labour was most commonly used for deep ploughing, shallow ploughing, animal weeding, pesticide application, and irrigation; female labour was most commonly used for sowing, hand weeding, and harvesting.6

Table 13 Labour absorption in non-Bt cotton, Dongargaon, 2006—07 in number of 8-hour days per acre

|

Operation |

Plots using machines |

Plots using bullocks/human labour |

||

|

Men |

Women |

Men |

Women |

|

|

Deep ploughing |

1 |

0 |

4 |

0 |

|

Shallow ploughing |

1 |

0 |

2 |

0 |

|

Sowing |

1 |

4 |

1 |

4 |

|

Animal weeding |

2–6 |

0 |

2–6 |

0 |

|

Hand weeding |

1–3 |

15–20 |

1–3 |

15–20 |

|

Fertilizer application |

0 |

2–3 |

0 |

2–3 |

|

Pesticide application |

1–2 |

0 |

1–2 |

0 |

|

Irrigation |

0–8 |

0 |

0–8 |

0 |

|

Harvesting and transport |

4–10 |

25–40 |

4–10 |

25–40 |

|

Total |

11–32 |

46–67 |

15–36 |

46–67 |

Note: The figures separated by a dash are for non-irrigated and irrigated plots, respectively.

Source: Survey data 2007.

In

cotton cultivation, the operation that accounted for the largest number of labour days was harvesting/picking, followed by hand

weeding. Female labour was predominantly used in both

these operations, leading to a significant rise in the overall level of female labour use in cotton. The spread of cotton cultivation

meant an immediate increase in the demand for female labourers

in picking and hand weeding.

The only

two operations for which machines were used in cotton cultivation were deep and

shallow ploughing. Mechanization of ploughing did not make a significant difference to the

total labour use in cotton, however; the use of

bullocks increased labour use by only about 4 labour days.

It is

clear that labour absorption in cotton rose significantly

between 1963–64 and 2006–07 (see Tables 12 and 13). Joshi (1967) estimated that about 34 labour days were used in cultivating cotton on 1 acre of

land in 1963–64. In 2006–07, on the other hand, even if plots that were mechanized and non-irrigated plots are

taken as a benchmark, the number of labour days was

57 per acre of land. On irrigated land under cotton, the extent of labour use was higher. A comparative study of crop

operations as described in Joshi (1967), and the accounts of peasants belonging to the older

generation as recorded in interviews conducted during the 2007 survey, shows

that there have been several changes in the methods of cultivation in the

village, which have had an effect on labour use.

These were as follows.

First,

one of the most important reasons for the overall increase in labour use in cotton was the rise in labour

use in the picking operation. Between 1963–64 and 2006–07, there was an

increase in the average yield of non-Bt cotton in Dongargaon

from about 1.8 quintals per acre to about 2.8 quintals per acre (Table 14). In

1963–64, owing to lower yield levels, there were just two rounds of pickings in

cotton. The increase in yield led both to more rounds of pickings and to higher

intensity at each picking. As a result, more labour

days went into the picking of cotton in 2006–07, when there were about four to

five rounds of picking even on non-irrigated plots. The larger part of the

overall increase in labour days was accounted for by

female labour days.

Table 14 Average yields of major monocrops, Dongargaon, 1963–64 and 2006–07 in quintals/acre

|

Crop |

Yield in 1963 (in Q) |

Yield in 2007 (in Q) |

|

Sorghum |

3.5 |

7.5 |

|

Cotton |

1.8 |

2.8 |

|

Bt cotton |

- |

6.8 |

|

Red gram |

3.5 |

3.7 |

|

Wheat |

3.5 |

9.0 |

Source: Joshi (1967); survey data 2007.

Secondly,

the area under cotton in the village increased significantly between 1963–64

and 2006–07. And since a unit area of cotton absorbed more labour

days than a unit area of sorghum, there was a corresponding rise in the demand

for labour use.

Thirdly,

the weeding operation in cotton cultivation appears to have gained in

importance between the 1960s and the 2000s. In 1963–64, there were just two

rounds of weeding, one using the dawara (plough) and bullocks, and the other with human labour. In 2006–07, on the other hand, there were two to

three rounds of hand weeding, in addition to one round of animal weeding using

the dawara.

While male workers were employed in animal weeding, a task that could be completed

by them in one day for 1 acre of land, women workers were predominantly

employed in the more labour-intensive task of hand

weeding. The increase in the rounds of hand weeding led to a rise in female labour absorption in cotton cultivation between 1963–64 and

2006–07.

Fourthly,

fertilizers and pesticides were generally not used in cotton cultivation in

1963–64 (Joshi 1967), when

5 to 10 carts of manure per acre of cotton was the only known form of nutrient.

By 2007, however, most of the cotton farmers were using fertilizers and

pesticides, with female workers engaged in the application of fertilizers and

male workers in pesticides. The labour days used in

the application of fertilizers and pesticides in 2007 was larger in number than

the labour days used for applying manure in 1963.

Fifthly,

the increase in spread of irrigation in Dongargaon

between the 1960s and 2000s had a major impact on labour

absorption. The extent of labour use on non-irrigated

and irrigated plots differed. An additional 8 labour

days per acre were used on irrigated land. If there were one or two rounds of

animal weeding and hand weeding on non-irrigated plots, there were at least

three rounds of these operations on irrigated plots. As the yields were higher,

there were also more rounds of picking on irrigated plots than on non-irrigated

plots. Further, as there was a larger quantity of the harvested cotton to be

transported from irrigated plots, the number of labour

days used for transportation was also higher in these.

Sixthly,

a cotton cultivation operation in which there was a decline in labour absorption in 2007 as compared to 1963 was ploughing. In 1963–64, ploughing

was a painstaking operation in the village. Joshi noted that “manuring with 5 to 10 cart loads was a common practice”,

and that “mixing [the manure] and harrowing with 3 to 4 times was followed” (Joshi 1967, p. 93). Interviews

conducted in the village during the 2007 survey revealed that the ploughing operation on plots of hard soil involved just one

round of nangarne

(deep ploughing) followed by one round of mogda (breaking

clods of soil with a long wooden hammer). Thus, as noted by Joshi, whereas 8

male labour days and 2 female labour

days were required to complete the preparatory tillage in 1963–64, in 2006–07

the norm was one round of deep ploughing, largely

with tractors and sometimes with bullocks, followed by one round of shallow ploughing. The task of deep ploughing

on 1 acre of land could be completed by one day of male labour

with tractor or four days of male labour with

bullocks; similarly, one labour day with a tractor or

two labour days with bullocks could complete the task

of shallow ploughing on 1 acre of land. The mogda operation

was not required in 2006–07 because the superior quality of the ploughshares

ensured that very few clods of soil remained after nangarne; and if clods were

present, they were broken by means of a panchi (a heavy, five-blade metal plough used to turn the

land) or a thiree

(a heavy, three-blade metal plough used to turn the land), as a part of the nangarne contract

itself.

In sum,

between the 1960s and 2000s, there was (i) a fall in

the number of male labour days employed in ploughing; (ii) a rise in the number of male labour days used in pesticide application and irrigation

(on irrigated plots); and (iii) a significant rise in the number of female labour days employed in weeding and harvesting.

Labour Use in Bt Cotton

The number of labour days used in the

cultivation of Bt cotton in Dongargaon in 2006–07 are

given in Table 15. Since Bt cotton came to the village only in 2003–04, a

comparison of labour absorption between the years

1963–64 and 2006–07 could be made only for non-Bt cotton cultivation.

By 2006–07,

the introduction of Bt cotton had brought about a significant rise in labour absorption in cotton in the village (Table 15). Even

where machines were used, a non-irrigated plot of Bt cotton accounted for as

many as 143 labour days (38 male and 105 female). On

irrigated plots using machines, the number of labour

days used was higher still, going up to 194. As was the case with non-Bt cotton

cultivation, in Bt cotton, too, the use of machines did not result in a

significant reduction in the level of labour

absorption. Also, much of the difference in the number of labour

days between non-Bt cotton and Bt cotton arose from the increased use of female

rather than male labour in the latter.

Increased

labour absorption in Bt cotton as compared to non-Bt

cotton can be traced to a set of factors. First, Bt cotton had higher yields

than non-Bt cotton, at 6.8 quintals per acre on an average. Higher yields, in

turn, meant more rounds of pickings and the use of a larger number of labour days in each picking. If there were four or five

rounds of picking for non-Bt cotton, Bt cotton allowed for six to seven rounds.

Some farmers in the village began picking in November and continued the

operation till February the next year, with some inter-cropping of vegetables

in the intervening months. The higher yields of Bt cotton also implied that the

labour engaged in the transportation of the produce

after picking was higher.

Table 15 Labour absorption in Bt cotton, Dongargaon, 2006–07 in number of 8-hour days per acre

|

Operation |

Plots using machines |

Plots using bullocks/human labour |

||

|

Men |

Women |

Men |

Women |

|

|

Deep ploughing |

1 |

0 |

4–8 |

0 |

|

Shallow ploughing |

3–2 |

0 |

3–2 |

0 |

|

Row making |

1 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

|

Sowing |

1 |

3–2 |

1 |

3–2 |

|

Animal weeding |

6–4 |

0 |

6–4 |

0 |

|

Hand weeding |

5 |

30–15 |

5 |

30–15 |

|

Fertilizer application |

2–1 |

3–2 |

2–1 |

3–2 |

|

Pesticide application |

3–2 |

0 |

3–2 |

0 |

|

Irrigation |

0–8 |

0 |

0–8 |

0 |

|

Harvesting and

transport |

20 |

60–120 |

20 |

60–120 |

|

Total |

38–49 |

105–145 |

41–56 |

105–145 |

Note: The figures separated by dashes are for non-irrigated and irrigated plots, respectively.

Source: Survey data 2007.

Secondly,

farmers carried out each operation in Bt cotton cultivation with greater care,

as compared to non-Bt cotton. Thus, both for deep ploughing

of plots using only human labour, and for shallow ploughing of plots using human labour

and machines, an additional round of ploughing was

the norm. In both these kinds of ploughing, the

increased labour use was in male labour

days. Similarly, there was an additional round of animal weeding and hand weeding

in Bt cotton plots, as compared to non-Bt cotton plots. Also, additional

amounts of fertilizers and new pesticides were applied in Bt cotton plots,

which again meant use of more labour. While the

additional round of animal weeding raised the use of male labour

days, the additional round of hand weeding and increased fertilizer and

pesticide application raised the use of female labour

days.

Thirdly,

while sowing of non-Bt cotton was undertaken with seed-drills (tiphan), Bt

cotton was sowed manually by placing the seeds by hand on furrows (zari) in the

field. Construction of furrows and manual sowing methods meant that a larger

number of labour days were used in Bt cotton.

In sum,

the shift of land under cotton cultivation from non-Bt cotton to Bt cotton

involved greater labour use, with the increase in the

number of female labour days being larger than the

increase in the number of male labour days.

Labour Use in Sorghum

In plots

where sorghum was grown as a mono-crop, the number of labour

days was smaller than in plots where non-Bt cotton was grown as a mono-crop.

Sorghum was almost exclusively grown in non-irrigated plots. In plots that had

mechanized operations using tractors, the number of labour

days was 37 per acre, while in plots that used human labour

or bullocks, the number of labour days was 40 per

acre (Table 16). A feature of labour absorption in

sorghum cultivation was that, just as in cotton, the female labour

days used was higher than the male labour days.

Table 16 Labour absorption in sorghum, Dongargaon, 2006–07 in number of 8-hour days per acre

|

Operation |

Plots using machines |

Plots using bullocks/human labour |

||

|

Men |

Women |

Men |

Women |

|

|

Deep ploughing |

1 |

0 |

4 |

0 |

|

Shallow ploughing |

2 |

0 |

2 |

0 |

|

Sowing |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

|

Animal weeding |

2 |

0 |

2 |

0 |

|

Hand weeding |

0 |

14 |

0 |

14 |

|

Fertilizer application |

1 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

|

Harvesting |

2 |

6 |

2 |

6 |

|

Threshing |

2 |

3 |

2 |

3 |

|

Total |

12 |

25 |

15 |

25 |

Source: Survey data 2007.

In 1963–64,

the number of labour days used in sorghum was 24 days

per acre, within which the number of male labour days

was 14.5 days. In other words, between the 1960s and 2000s, the share of female

labour days used in sorghum cultivation rose and

surpassed the number of male labour days. The major

changes that took place during this period in the number of labour

days used in sorghum were as follows.

First,

as in cotton, there was a significant rise in the yield of sorghum. Between

1963–64 and 2006–07, the yield per acre of sorghum increased from 3.5 quintals

to 7.5 quintals. The rise in yield, in turn, resulted in a rise in the number

of labour days used in harvesting, threshing, and

transportation. If only 7.5 labour days per acre were

used in the harvesting and threshing of sorghum in 1963–64, the corresponding

figure for 2006–07 was 13 labour days. Further, in

both harvesting and threshing, the predominant labour

days used shifted from male labour days in 1963–64 to

female labour days in 2006–07.

Secondly,

the number of labour days used in weeding increased

between 1963–64 and 2006–07. In the earlier period, there were two rounds of

weeding in sorghum cultivation, both of which were undertaken with the aid of

bullocks and a full-blade hoe (kolpi), and which required the use of two male labour days and three female labour

days per acre. In 2006–07, two rounds of hand weeding were undertaken in

addition to two rounds of animal weeding, and the number of female labour days used in hand weeding alone was 14 per acre.

Thirdly, there was a fall in the number of male labour days used in ploughing, due to the changes that had come about in the nature of preparatory tillage for sorghum, between the 1960s and 2000s. In 1963–64, according to Joshi, “preparatory tillage in sorghum consists of multiple harrowings. Ploughing for sorghum is not a practice in vogue. Two to four harrowings are given after the removal of stalks” (Joshi 1967, p. 92). In 2006–07, preparatory tillage included one round each of deep ploughing (ploughing, as in Joshi) and shallow ploughing (harrowing, as in Joshi).7

Thus,

there was an increase in the total number of labour

days per acre used in sorghum cultivation between 1963–64 and 2006–07. Much of

this increase was accounted for by female labour

days; for men, there was a marginal fall in the number of labour

days used under conditions of mechanization/tractorization.

Labour Use in Inter-crops of

Cotton, Sorghum, and Red Gram

In this

section of the paper on labour use in inter-crops,

only the three major types of inter-cropping seen in Dongargaon

in 2006–07 are considered, namely, cotton–red gram, cotton–sorghum, and sorghum–red

gram. All these crop combinations had the following set of operations in

common: ploughing, sowing, weeding, and fertilizer

application. Considering the labour days across these

operations as common, the differences in labour use

for each crop combination are provided in Table 17.

First,

among the three crop combinations, there was a rise in the labour

days used wherever cotton was involved. Cotton picking is a highly

employment-intensive operation compared to sorghum or red gram harvesting, and

therefore labour absorption was higher when cotton

was a part of the crop combination. Thus, while the total number of labour days in mechanized plots using tractors was 74 per

acre in cotton–red gram and 69 per acre in cotton–sorghum, it was only 33 per

acre in sorghum–red gram. However, in all the crop combinations, the

predominance of female labour days was evident. Here

again, the difference between the number of male and female labour

days was wider where cotton was involved as an inter-crop.

Table 17 Labour absorption in intercrops, Dongargaon, 2006–07 in number of 8-hour days per acre

|

Operation |

Plots using machines |

Plots using bullocks/human labour |

||

|

Men |

Women |

Men |

Women |

|

|

Common operations: |

|

|

|

|

|

Deep ploughing |

1 |

0 |

4 |

0 |

|

Shallow ploughing |

2 |

0 |

2 |

0 |

|

Sowing |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

|

Animal weeding |

2 |

0 |

2 |

0 |

|

Hand weeding |

0 |

14 |

0 |

14 |

|

Fertilizer application |

1 |

0 |

1 |