ARCHIVE

Vol. 11, No. 2

JULY-DECEMBER, 2021

Editorials

Research Articles

Research Notes and Statistics

Review Articles

Tribute

Caste Discrimination in the Provision of Basic Amenities:

A Note Based on Census Data for a Backward Region of Maharashtra

*Senior Research Fellow, Indian Statistical Institute, Bengaluru, nageshwar_rs@isibang.ac.in

**Indian Statistical Institute, Bengaluru, madhura@isibang.ac.in

https://doi.org/10.25003/RAS.11.02.0007

Introduction

The Marathwada region of Maharashtra, which comprises the districts of Aurangabad, Beed, Hingoli, Jalna, Latur, Nanded, Osmanabad and Parbhani, is officially classified as a “backward region” and is relatively under-provided with respect to social and economic infrastructure (YASHADA 2014). Marathwada also has a substantial Dalit population: the population of people of the Scheduled Castes as a proportion of the population of the districts was 16 per cent (the corresponding proportion for the State as a whole was 12 per cent).1 There are only a few studies of the socio-economic status of Dalit households in the Marathwada region of Maharashtra (Bakshi 2008, Bokil 1996, Ramakumar and Kamble 2012).

The Government of Maharashtra created the Marathwada Development Board in 1994 to address problems of the socio-economic development of the people of the region. The three most underdeveloped districts (Nanded, Hingoli, and Aurangabad) are covered by the Backward Regions Grant Fund (BRGF), a 100 per cent Centrally-Assisted Scheme of the Government of India begun in 2007-08. The BRGF provides special funds to less-developed districts to create new village-level physical infrastructure and amenities.

In this Note, we use data at the village level from the Census of India 2011 for eight districts of Marathwada to examine the availability of civic amenities in relation to the caste composition of villages. We find substantial inequalities in the distribution of social and economic infrastructure across villages grouped by the proportion of Scheduled Castes in the population.

Our argument is that the civic amenities available to people change as the caste composition of a village changes. The greater the share of people of the Scheduled Castes in a village, the greater the underdevelopment of village-level physical and social infrastructure. This holds true for indicators of health, education, banking, communication, and other infrastructure. Backwardness is a form of externality in that all people in a locality are adversely affected by it irrespective of their individual economic status or endowments.

Data and Method

This paper examines data on the availability of basic amenities for the villages of the Marathwada region, which number more than 8000. The major source of data for this paper is the District Census Handbook of the Census of India (2011). The unit of analysis is the Census village.

For our analysis, first, in each district, we excluded all villages in the Census of India that were uninhabited or with a population of less than 10 persons. Secondly, in order to focus attention on the people of the Scheduled Castes, we excluded Scheduled Tribe-dominated or Adivasi villages. Specifically, villages with no Scheduled Castes but with Scheduled Tribes were excluded, as were multi-caste villages that had a Scheduled Caste population but in which the number of Scheduled Tribes exceeded 20 per cent of the total population. To illustrate, as shown in Table 1, in Nanded district, there were a total of 1603 villages at the Census of 2011, of which 62 were uninhabited and 11 villages had a population of less than 10 persons each. There were 70 villages with no Scheduled Castes, but some Scheduled Tribes, and there were 249 villages where the Scheduled Tribe population exceeded 20 per cent of the population. The final list for Nanded district thus comprised 1211 villages.

Table 1 Number of villages by population characteristics, Nanded district, Maharashtra.

| Sr. No. | Village type | Number of villages |

| 1 | Census villages | 1603 |

| 2 | Inhabited villages | 1541 |

| 3 | Uninhabited villages | 62 |

| 4 | Villages with a population of 10 or less people | 11 |

| 5 | Villages with population of ST and no SC population | 70 |

| 6 | Villages with ST population exceeding 20 per cent of total population | 249 |

| 7 | Selected villages (2-4-5-6) | 1211 |

Source: Census of India 2011

Applying the same method to 8529 Census villages in the eight districts, our analysis identified 7589 villages for further study (Appendix Table 1).

Secondly, we ranked all villages in a district by the proportion of Scheduled Castes in the total population. We then grouped villages into eight fractile groups, based on centiles of Scheduled Caste persons in the population of each village (Table 2). (Villages within each fractile group did not differ much in terms of population size.)2

Table 2 Population, number of villages and average size of village for villages ranked by proportion of Scheduled Castes in total population, Nanded district, Maharashtra, 2011

| Fractile group | Centile (Per cent of SCs in total population) | Total population | Number of villages | Average size |

| 1 | 0-10 | 287804 | 290 | 992 |

| 2 | 10-20 | 638573 | 307 | 2080 |

| 3 | 20-30 | 696793 | 353 | 1974 |

| 4 | 30-40 | 271613 | 177 | 1535 |

| 5 | 40-50 | 77739 | 63 | 1234 |

| 6 | 50-60 | 9224 | 11 | 839 |

| 7 | 60-70 | 3356 | 4 | 839 |

| 8 | 70-100 | 2472 | 6 | 412 |

| All | All | 1987574 | 1211 | 1238 |

Source: Census of India, 2011.

Thirdly, we used data from the District Census Handbook of the Census of India 2011 pertaining to educational amenities, health facilities, and other amenities. We tabulated (and plotted) data on villages in different fractile groups with that on availability of amenities.

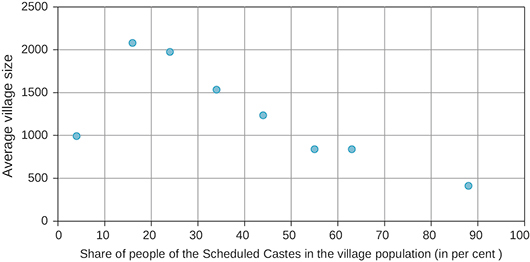

A noteworthy fact is a systematic negative relation between the size of village in terms of population and the proportion of the people of the Scheduled Castes in the population (excluding the first fractile). The data for Nanded district (in Table 2 and Graph 1) show, for example, that in villages in which people of the Scheduled Castes constituted between 10 and 20 per cent of the population (fractile group 2), the average village population was 2080. In villages in which people of the Scheduled Castes constituted more than 50 per cent of the population (fractile groups 6, 7, and 8), the average village population was less than 900 persons. The same pattern occurred in all districts.3

Graph 1 Average population per village for villages ranked by proportion of Scheduled Castes in total population Nanded, 2011

Source: Census of India 2011

Variables

With respect to educational institutions, the Census covers all schools, and colleges, including professional colleges. The Census provides data separately for government and private institutions. We focus on middle schools, secondary schools and senior secondary schools, defined as follows:

Middle Schools (M): Middle schools refer to schools that cover classes VI to VIII.

Secondary Schools (S): Secondary schools refer to schools that cover classes IX to X.

Senior Secondary Schools (SS): Senior Secondary schools refer to schools that cover classes XI and XII.

We have used information on the following health facilities in each village: Community Health Centres (CHCs), Primary Health Centres or Sub-Centres (PHCs), Maternity and Child Welfare Centres, and Tuberculosis (TB) clinics.

The Census of India provides village-level data on the availability of the following amenities: tap water, drainage, and electricity; bank and credit facilities (ATMs, commercial banks, cooperative banks and agricultural credit societies); communication and transport facilities (post offices, public buses, and private bus services); and miscellaneous amenities (ration shops, mandis or regular markets, pre-school child care centres or Anganwadis, and public libraries.)

We have normalised all variables by population size, and report data on the number of amenities available per 10,000 persons.

Results

We report results for Nanded district in this paper. In 2006, the Ministry of Panchayati Raj named Nanded as one of the country's 250 most backward districts (out of a total of 640). Where results for other districts differ from those of Nanded, they are discussed in the text. Results for all eight districts are available on request.

Education

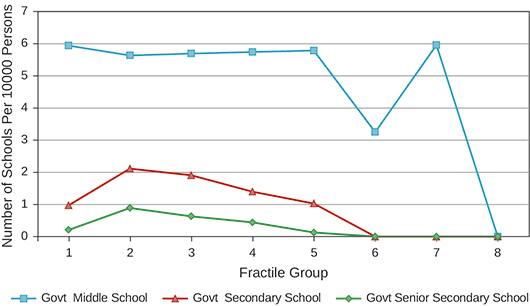

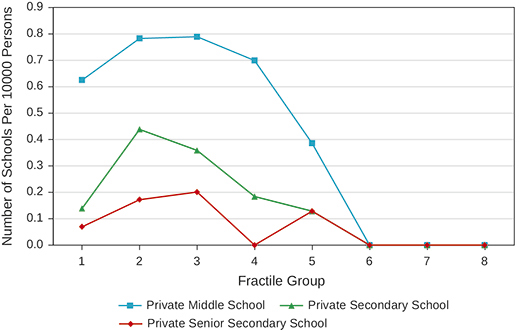

With respect to school infrastructure per 10,000 persons, there are two features of note (Graphs 2 and 3, Appendix Tables 2 and 4).

Graph 2 Government schools per ten thousand persons for villages ranked by proportion of Scheduled Castes in total population, Nanded district, 2011

Source: Census of India 2011

Graph 3 Private schools per ten thousand persons for villages ranked by proportion of Scheduled Castes in total population, Nanded district, 2011

Source: Census of India 2011

First, in the case of government secondary and senior secondary schools, the availability of schools was the highest in fractile 2, and was lower in all other fractiles. The availability was almost nil for villages in fractile 6 and above. To put it differently, there was no government Secondary or Senior Secondary school in villages where people of the Scheduled Castes comprised more than one-half of the village population. The number of middle schools per 10,000 persons was almost same in villages in different fractile groups with a few exceptions.

The pattern for private schools was similar (Graph 3). Here, even the availability of middle schools was much lower in fractile 4 and above than in fractile 2 and 3. In other words, in villages where government schools are not present, neither are private schools.4

It can be argued that the availability of social infrastructure is not related to caste composition of the population but to the size of the village, as larger villages may have more amenities. To distinguish between the issue of size of the Dalit population and of the overall population, we also examined the availability of schools for villages of different population size within each fractile group (Appendix Table 3). Within a fractile group, the number of government secondary schools per 10,000 persons was higher for larger villages. However, in similar-sized villages, those with a higher proportion of Scheduled Castes were less well served than those with a lower proportion of Scheduled Castes. For example, for all villages in the 1000-1500 size-class, there were no government secondary school in fractile 5 and above. In short, while the size of a village does seem to be related to the availability of amenities, the composition of the population in terms of the relative size of the Dalit population matters too.

The results were similar for other districts of the region, indicating that in rural Marathwada, physical access to schooling is lower for villages with a higher proportion of Dalits.

Health

With the exception of Primary Health Centres, all basic health amenities – TB clinics, maternity and child welfare centres, community health centres - are absent in villages in fractile group 5 and above, that is, in villages where Scheduled Castes comprise more than 40 per cent of the population (Table 3).

Table 3 Health amenities per ten thousand persons for villages ranked by proportion of Scheduled Castes in total population, Nanded district, 2011, in number

| Fractile Group | Community Health Centre | Primary Health Centre | Maternity And Child Welfare Centre | TB Clinic |

| 1 | 0.03 | 1.4 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| 2 | 0.02 | 1.9 | 0.4 | 0.4 |

| 3 | 0 | 2.1 | 0.3 | 0.3 |

| 4 | 0 | 1.4 | 0 | 0 |

| 5 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Source: Census of India 2011

Here too we checked the availability of amenities by size of village and found that similar-sized villages in fractile 1 (less than 10 per cent of the population comprising Scheduled Castes) had more amenities than those in the last two fractiles. (Note that all these are for population adjusted numbers.)

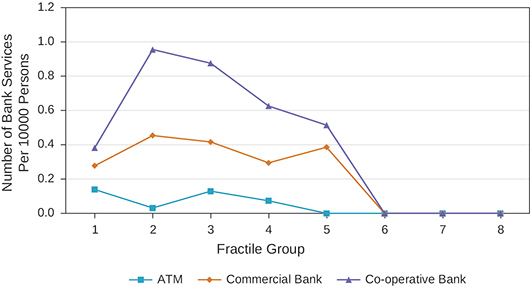

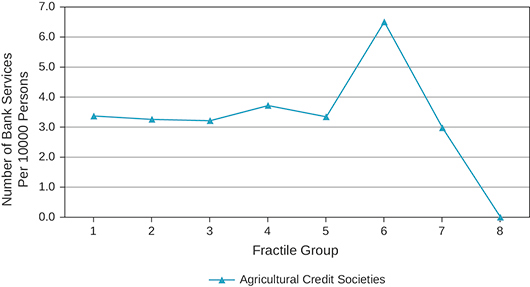

Modern Banking and Credit Facilities

The Census of India gives information on availability of ATMs, commercial banks, cooperative banks and agricultural credit societies at the village level. There was no ATM, or branch of a commercial bank or cooperative bank in any village in fractile group 6, 7, and 8 (Graphs 4, 5 and Appendix Table 5).

Graph 4 Bank services per ten thousand persons for villages ranked by proportion of Scheduled Castes in total population, Nanded district, 2011

Source: Census of India 2011

Graph 5 Agricultural credit societies per ten thousand persons for villages ranked by proportion of Schedule Castes in total population, Nanded district, 2011

Source: Census of India 2011

The most widespread credit institution in the rural areas of Nanded district was the Primary Agricultural Credit Society or PACS. Even PACS were absent in fractile group 8, and present in only 8 of the 22 villages where Scheduled Castes comprised more than 50 per cent of the total population.

Communication and Transport

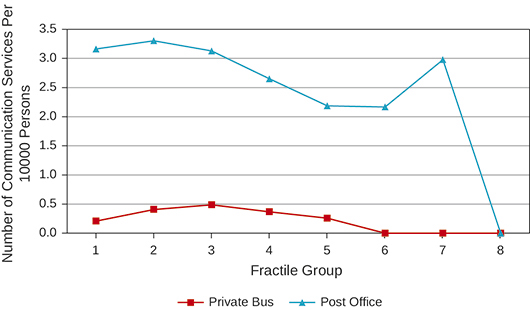

Next, we examined access to communication and transport facilities (Graph 6 and Appendix Table 6).

Graph 6 Communication and transport facilities per ten thousand persons for villages ranked by proportion of Schedule Castes in total population, Nanded district, 2011

Source: Census of India 2011

Public bus services are essential for the poor and for workers to travel within and beyond the district. Only 82 per cent of villages with Scheduled Castes in a majority reported a public bus service, and none had a private bus service. Further, only five out of 22 had a post office.

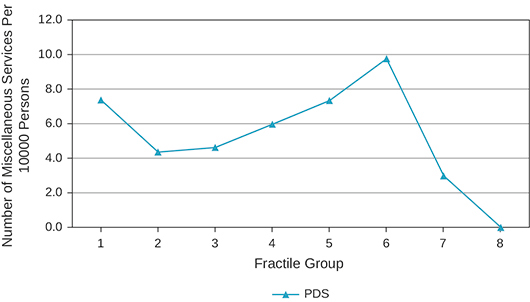

Lastly, we examined the presence of ration shops under the Public Distribution System (PDS), regular markets, anganwadis (child care centres), and public libraries (Graphs 7 and Appendix Table 7). There was an anganwadi in every village, the one success story in terms of social infrastructure. PDS shops were in a large majority of villages in all fractile groups except the last. This is worrisome given the likelihood of high dependence on PDS in villages in fractile group 8.

Graph 7 Public Distribution System shops per ten thousand persons for villages ranked by proportion of Scheduled Castes in total population, Nanded district, 2011

Source: Census of India 2011

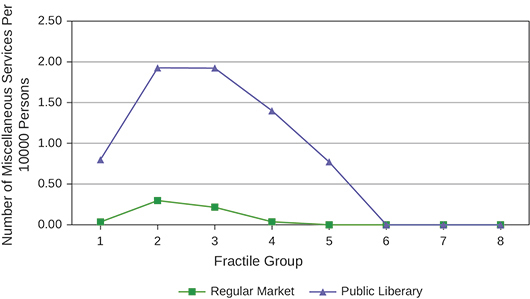

There was no public library nor a regular market in any of the villages in fractile groups 6 and higher (Graph 8).

Graph 8 Number of regular markets and public libraries per ten thousand persons for villages ranked by proportion of Scheduled Castes in total population, Nanded district, 2011.

Source: Census of India 2011

Concluding Remarks

This paper undertook an exercise based on data from the District Census Handbook of the Census of India 2011 for eight districts of Marathwada, a backward region of Maharashtra. The paper ranked villages by the share of Scheduled Castes in the total population, grouping them in to fractiles, and then examining the availability of basic social and economic amenities (normalised by population) across villages in different fractile groups. It is worth noting that the data show a consistent pattern across all eight districts, although we reported data from Nanded district to illustrate the findings.

The availability of a range of basic amenities, including schools, health facilities, banking, communication and transport varied with the caste composition of a village. We found that in Nanded district, which along with the entire region of Marathwada is relatively backward with poorly developed social and economic infrastructure, the availability of a range of amenities was lower in villages with a higher proportion of Scheduled Castes.

The higher the proportion of people of the Scheduled Castes in a village, the worse the access of the people of the village to basic amenities. In the case of villages where Scheduled Castes comprised 50 per cent or more of the population, the availability of basic health amenities and schools was often nought. Poor transport infrastructure compounds the problems created by the absence of health and school facilities within a village.

Another finding of note is that the private sector failed to fill the gap in infrastructure provided by the public sector. For example, in villages with no government school, there was no private school either. In villages with no public bus service, there was no private bus service.

Even though the absolute number of villages with a high proportion of Scheduled Castes was small (for example, there were 21 villages in fractile group 6 to 8 in Nanded district), this doesn’t take away from the systematic pattern of deprivation in respect of social infrastructure. This lack of basic amenities is a negative externality for all households, irrespective of economic status, residing in these villages.

There is an important caveat here. Villages with a high proportion of Scheduled Castes tend to be relatively small villages in terms of population size. In general, social infrastructure was better in larger-sized villages. However, we found that the share of the Dalit population mattered, as even within a specific population size-class, villages in the higher fractile groups had fewer amenities than those in the lower fractile groups.

If the size of population becomes a key factor in planning of social infrastructure, then villages where Scheduled Caste persons are in a majority are likely to remain under-served with respect to basic amenities. At the same time, the problem can clearly be addressed given that in absolute numbers, such villages are few (21 in Nanded and 46 in all of Marathwada).

To address the lack of access to basic amenities and social infrastructure for Scheduled Castes on account of locational discrimination, we argue that public policies within a “backward region” must directly focus on such absences in villages in which people of the Scheduled Castes comprise a large section of the total population.

Acknowledgements: We are grateful to the referees for their comments.

Notes

2 The coefficient of variation of size of a village within a fractile group was less than one for all fractile groups.

3 The average population size of villages in which people of the Scheduled Castes were a majority (more than 50 per cent of the population) was lower than the average size of all villages in each district.

References

| Bakshi, A. (2008), “Social Inequality in Land Ownership in India: A Study with Particular Reference to West Bengal,’’ Social Scientist, vol. 36, no. 9/10, pp. 95-116. | |

| Bokil, M. (1996), “Privatisation of Commons for the Poor: Emergence of New Agrarian Issues,” Economic and Political Weekly, vol. 31, no. 33, pp. 2254-2261. | |

| Census of India (2011), District Census Handbook, Maharashtra, 2011 available at https://censusindia.gov.in/2011census/dchb/DCHB.html | |

| Ramakumar, R., and Kamble, T. (2012), “Land Conflicts and Attacks on Dalits: A Case Study from Marathwada, India,” Review of Agrarian Studies, vol. 2, no. 2, pp. 120-135. | |

| Yashwantrao Chavan Academy of Development Administration (YASHADA) (2014), Maharashtra Human Development Report 2012, Towards Inclusive Human Development, Sage Publications, New Delhi, available at https://mahasdb.maharashtra.gov.in/docs/pdf/mhdr_2012.pdf, viewed on December 28, 2021. |

Appendix

Appendix Table 1 Number of villages by type of village and final selection, seven districts of Marathwada, Maharashtra, Census of India 2011

| Sr. No. | Type of villages | Aurangabad | Beed | Hingoli | Jalna | Latur | Osmanabad | Parbhani |

| 1 | Census villages | 1356 | 1368 | 711 | 967 | 948 | 733 | 843 |

| 2 | Inhabited villages | 1314 | 1357 | 675 | 958 | 928 | 728 | 830 |

| 3 | Uninhabited villages | 42 | 11 | 34 | 9 | 20 | 5 | 13 |

| 4 | Villages with a population of 10 or less people | - | - | 1 | - | - | - | - |

| 5 | Villages with ST and no SC | 52 | 28 | 34 | 3 | 7 | 4 | 13 |

| 6 | Villages with ST population exceeding 20 per cent of total population | 87 | 3 | 105 | 19 | 20 | 11 | 25 |

| 7 | Selected villages (Sr. No. 2-4-5-6) | 1175 | 1326 | 535 | 936 | 901 | 713 | 792 |

Note: We have found villages with less than 10 persons reported only for Nanded and Hingoli districts.

Source: Census of India 2011.

Appendix Table 2 Government schools per ten thousand persons for villages ranked by proportion of Scheduled Castes in total population, Nanded district, 2011 in number

| Fractile Group | Middle | Secondary | Senior Secondary |

| 1 | 5.9 | 1.0 | 0.2 |

| 2 | 5.6 | 2.1 | 0.9 |

| 3 | 5.7 | 1.9 | 0.6 |

| 4 | 5.7 | 1.4 | 0.4 |

| 5 | 5.8 | 1.0 | 0.1 |

| 6 | 3.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| 7 | 6.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| 8 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

Source: Census of India 2011

Appendix Table 3 Government secondary schools per ten thousand persons for villages ranked by proportion of Scheduled Castes in population and size class of population, Nanded 2011 in number

| Centiles | Size class of population | |||||

| 0-500 | 500-1000 | 1000-1500 | 1500-2000 | 2000-2500 | 2500-3000 | |

| 0-10 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.3 |

| 10-20 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 1.5 |

| 20-30 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.4 | 1.2 |

| 30-40 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| 40-50 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.4 |

| 50-60 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | - | - |

| 60-70 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | - | - | - |

| 70-100 | 0.0 | - | - | - | - | - |

Source: Census of India 2011

Appendix Table 4 Private schools per ten thousand persons for villages ranked by proportion of Scheduled Castes in total population, Nanded district, 2011 in number

| Fractile Group | Middle | Secondary | Senior Secondary |

| 1 | 0.6 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| 2 | 0.8 | 0.4 | 0.2 |

| 3 | 0.8 | 0.4 | 0.2 |

| 4 | 0.7 | 0.2 | 0.0 |

| 5 | 0.4 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| 6 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| 7 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| 8 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

Source: Census of India 2011

Appendix Table 5 Bank services per ten thousand persons for villages ranked by proportion of Scheduled Castes in total population, Nanded district, 2011 in number

| Fractile Group | ATM | Commercial Bank | Co-operative Bank | Agricultural Credit Societies |

| 1 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 3.4 |

| 2 | 0.0 | 0.5 | 1.0 | 3.3 |

| 3 | 0.1 | 0.4 | 0.9 | 3.2 |

| 4 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 0.6 | 3.7 |

| 5 | 0.0 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 3.3 |

| 6 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 6.5 |

| 7 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 3.0 |

| 8 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

Source: Census of India 2011

Appendix Table 6 Communication and transport facilities per ten thousand persons for villages ranked by proportion of Scheduled Castes in total population, Nanded district, 2011 in number

| Fractile Group | Private Bus | Post Office |

| 1 | 0.2 | 3.2 |

| 2 | 0.4 | 3.3 |

| 3 | 0.5 | 3.1 |

| 4 | 0.4 | 2.7 |

| 5 | 0.3 | 2.2 |

| 6 | 0.0 | 2.2 |

| 7 | 0.0 | 3.0 |

| 8 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

Source: Census of India 2011

Appendix Table 7 PDS, regular market, and public library facilities per ten thousand persons for villages ranked by proportion of Scheduled Castes in total population, Nanded district, 2011 in number

| Fractile Group | PDS | Regular Market | Public Library |

| 1 | 7.4 | 0.03 | 0.8 |

| 2 | 4.4 | 0.30 | 1.9 |

| 3 | 4.6 | 0.22 | 1.9 |

| 4 | 6.0 | 0.04 | 1.4 |

| 5 | 7.3 | 0.00 | 0.8 |

| 6 | 9.8 | 0.00 | 0.0 |

| 7 | 3.0 | 0.00 | 0.0 |

| 8 | 0.0 | 0.00 | 0.0 |

Source: Census of India 2011

Date of submission of manuscript: September 9, 2021

Date of acceptance for publication: October 31, 2021