ARCHIVE

Vol. 10, No. 2

JULY-DECEMBER, 2020

Editorials

Research Articles

Research Notes and Statistics

Review Articles

Agrarian Novels Series

Book Reviews

Dispossession and Agrarian Transition in Late Medieval England

*Professor Emeritus of International Studies, Simon Fraser University, Vancouver, jharriss@sfu.ca.

|

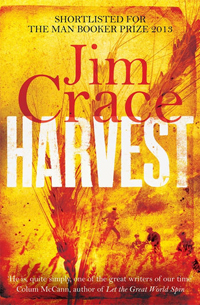

Jim Crace, Harvest.1

In the English countryside, walkers sometimes become aware of grassy mounds, rectangular in shape, beside the path they have been walking on, and may have the sense of being on a village street.2 Indeed they might have been, centuries ago, because there are many deserted villages in England that have been left behind only traces in the landscape (Dyer and Jones 2010). When research began on these former village sites, they were generally referred to as “deserted medieval villages,” and it was often supposed that their desertion had come about as a result of the Black Death, the global epidemic of bubonic plague that caused massive numbers of deaths across Asia and Europe in the mid-fourteenth century. It has come to be recognised, however, that the abandonment of villages and hamlets has been a constant feature of rural settlement in England – and very much more widely – over many centuries and up to the present, and that it is not specifically a phenomenon of the Middle Ages. It has also been recognised that the desertion of settlement sites has many possible causes, including – commonly enough – simply retreat from agroecologically marginal land. The Black Death was certainly another cause, though in England, research has shown that many to-be deserted villages survived till later in the fourteenth century. From that time, many more settlements were deserted as a result of the enclosure of what had been “open fields” and the displacement of those who had cultivated them. Of a village in Yorkshire, in northern England, for example, a text from 1514 says that the local lord “dydd caste doune the town of Willistrop, destroyed the corn feldes and made pasture on theym, and hath closed in the common and made a park of hytt” (Jones 2010, p. 23). As happened in “Willistrop” (now called Wilsthorpe), many settlements either shrank or were abandoned altogether as the open fields and the common lands were enclosed for pasture and for the grazing of sheep, which became an increasingly profitable enterprise because of the value of wool. Those who had farmed the land were dispossessed and displaced. As Jim Crace puts it in his novel Harvest, “The sheaf is giving way to sheep” (p. 41).

Harvest is a contemporary novel – it won the 2013 James Tait Black Memorial Prize and the 2015 International Dublin Literary Award, and was shortlisted for the 2013 Booker Prize. It tells the tale of the enclosure of a village and the dispossession of those who had lived there, a tale said by a reviewer of the book for The Guardian to be “one of the great under-told narratives of English history” (Jordan 2013). It is a story of the rise of capitalism, the disintegration of village communities, and of the “othering” of outsiders in a way that resonates powerfully in present times – and it has the quality of a myth or fable. Jim Crace never tells us where “the Village” – which is said to have had no name – is located, or when the events took place. One reviewer placed the events of the novel in the late sixteenth century, another in the seventeenth or eighteenth centuries. I think it is a story of late medieval England (perhaps the late fifteenth century), when enclosure for wool production began to gather pace and there were new lords in England who “were businessmen, determined, with the instincts of traders and the methods of bailiffs, to exploit their estates” (Myers 1952, p. 213) – which is exactly what is depicted in Harvest. The lack of historical specificity, however, and the apparent timelessness of the novel makes for its mythic quality. And while it is rich in descriptive writing that brings the countryside alive for the reader – Crace’s prose is often poetic – Harvest is far from being a pastoral novel projecting the idea of a rural idyll.

The novel opens just as the harvest has been completed. It is the morning after the end of harvest, and a day of rest and later of celebration. But there is smoke in the air, signaling that “New neighbours have arrived; they know the customs and law” – the customary law holding that, if people could build a place with four walls and a roof on common land overnight, lay a hearth and light a fire, then they had a right to settle. So “this first smoke has given them a right to stay” (p. 1). But there is a second twist of smoke, too, that causes people to rush toward the manor house of Master Kent, the lord of the village – although, significantly for the events that are to unfold, he is only lord by right of marriage. Kent’s “pretty dovecote” and his stables are on fire. The narrator, whom we come to know is a widower named Walter Thirsk, who came to the village first as Master Kent’s manservant twelve years before but married a local woman and was allowed by the lord to take up cultivation, is sure he knows who started the fire. He had seen three young men of the village returning from the woods, the evening before, with a sack of fairy cap mushrooms – which he knows well from his own experience are hallucinogenic – and a dried-out giant moonball (another kind of fungus). The latter, Thirsk is sure, the men had set on fire only to make smoke to drive the master’s doves from the dovecote, but it had ended up causing the blaze. Dovecotes – structures, often beautifully designed, for housing large numbers of doves – are still found in the grounds of many of the old manor houses and estates of England. The “snowy devils,” as the birds are described in the novel, “robbing fallen grain that, by ancient gleaning rights, should have been ours,” were always a cause of tension between the lords who owned them, and the commoners who cultivated the land and resented the birds “feasting on our bread and ale” (p. 9). The doves provided a source of meat in winter for the likes of Master Kent, but at the expense of grain that should have gone, the cultivators of the land believed, to them.

From its first pages, Harvest depicts the relationship between lord and peasant (Master Kent, as we learn, is far from being a very rich man, but he is the lord of the manor nonetheless) as a very delicate balance. Far as the village is from town, justice is administered locally, by Master Kent. He has power and authority. He has, perhaps, a shrewd idea of who was responsible for the fire that has caused so much damage, but he must weigh up the possibility of punishment against his need for manpower – and Walter the narrator has told the reader, “Our numbers have been too reduced of late to allow a single useful soul to stay away [from taking part in the harvest]” (p. 6). Later, he reflects upon the numbers of empty houses in the village and ruins like that of what was once the family home of Cecily, his wife. As in “the Village,” the challenge of securing sufficient manpower had to be confronted by the lords of the land across much of Europe and of Asia until changes such as those depicted in the novel brought in new systems of production.

There had been some anxiety among the harvesters on the day before harvest. Enjoyment of the work together and the lewd jokes that passed between them were gradually suppressed by speculation about a strange man – “a gentleman we did not recognise” – obviously a townsman, with a stiff gait and a fancy beard, who, with a drawing board, was “exactly marking down our land.” They nicknamed him “Mr Quill” and at first made jokes about him. But why was Mr Quill there? Eventually, the narrator tells us:

We shook our heads and searched our hearts, until we had persuaded ourselves that Master Kent was too good and just a man to sell our fields. He’d always taken care of us. We’d always taken care of him. (p. 9)

Kent owns the land – “His titles, muniments and deeds are witness to the truth of that” (p. 17) – but he depends on the labour of the villagers, and so “it is allowed for us to be possessive of this ground and the common rights that are attached to it” (p. 18). We, the readers, are warned from the first, however, that the bargain of patronage is under threat. A little later, in the course of the harvest feast that he has provided, Master Kent announces that the land will be enclosed for sheep. Walter’s fears that Kent, in spite of his character and his promises, “means to throw a halter round our lives” are proven justified. The Master, though, tries to present the plan as being for the benefit of everyone – there will be less toil and more wealth:

We have good years, we have bad, he reminds us . . . wool is more predictable . . . Master Kent has had a dream which makes us rich and leisurely . . . “A stirring prospect, isn’t it?” he says.

He has timed his revelation at a good moment, when his people have enjoyed his veal and his ale, and he their fellowship: “We’re in his debt this evening and know him well enough to want to trust his word, at least for now” (p. 41).

Master Kent is the lord of a village community with open fields – cultivated according to a common pattern (so the field where the barley had just been harvested should be ploughed for winter wheat) – but on which every person with hereditary rights granted by the lord of the manor customarily cultivated a strip of land, with common rights of pasturage.3 Their rights included gleaning on the open field after the harvest had been brought in, to collect what was left behind. The yearly custom of the Village was to identify a “Gleaning Queen” from among the girls and young women, and gleaning was only to start after the Gleaning Queen had picked the first grains. The tradition was (historical sources tell us: Hussey 1997) that the Queen should have authority to ensure that there was fairness in access to a significant common resource. In the Village, the Gleaning Queen should have been nominated at the harvest feast but, because of the crisis that is developing in the community, has not been and so is chosen the morning after. This means ill-luck, Walter fears, and his presentiments of misfortune are deepened when Master Kent seems to suggest that the field where the barley grew will not be ploughed, as usual, for winter wheat: “It’s possible that Master Kent does not expect our ploughs to be in use again” (p. 64). Then Kent deputes Mr Quill to select the Gleaning Queen, and he, after pondering the more mature and buxom young women at some length, at last selects a little five-year-old girl. She is quite overcome, “not entirely sure of what she’s supposed to do,” and cannot really fulfill the customary duties of the Gleaning Queen. With hindsight, it may be taken as another sign of the breaking down of the community.

The crisis that quickly destroys the community starts with the arrival of the newcomers who had built their hut, made their hearth, and lit their first fire. Once the blaze that threatened to destroy Manor House has been extinguished, the people of the village set out to meet the newcomers, “equipped with sticks and staves.” This makes sense, Walt muses, “when there is little wealth and all our labours are spent in putting a single meal in front of us each day, to be protective of our modest world and fearful for our skinny lives” (p. 17). The harvests, latterly, have been niggardly. Why should the Village share with strangers? Walter reflects, though, that the Village is “hard-pressed for younger men and women,” and he thinks:

we have tenancy to spare, and could easily provide some newcomers a place to live, if the village was only minded to be less suspicious of anyone who was not born with local soil under their fingernails. (p. 20)

But suspicious they are, and the newcomers are blamed, conveniently but evidently quite unjustly, for having started the fire at the manor, and the two men – themselves “fugitives from sheep” (p. 147) – who had threatened the village people with their longbows drawn, have their heads shaven. Then they are put, at Master Kent’s command, for one week, into the pillory that stands at the entrance to the land supposed to be the churchyard, though there is still no church. It is the first time that the pillory – “it’s been our village cross” – has been used in many years. Both Walter and Kent – the last outsiders, in fact, to have been accepted into the village – evidently feel uneasy about the punishment that has been meted out.

The striking looking woman who accompanied the men, the daughter of the older man it seemed and probably the sister of the younger one, is wrapped in a very expensive looking shawl. She excites the men of the Village as being, apparently, available, whereas “the local women were like land, fenced in, assigned and spoken for, the freehold of their fathers, then their husbands, then their sons” (p. 28). She too has her head shaven, for her insolence to Kent, and then she disappears, only to reappear again just as the harvest feast is reaching a joyous climax, with music and dancing. “’It’s Mistress Beldam’, Master Kent mutters to me [Walter the narrator] . . . Beldam, the sorceress. Belle Dame, the beautiful.” Even at the beginning of the evening, Walter had felt that “our village is unnerved . . . there’s none of us who feels entirely comfortable, who is not soiled with a smudge of shame” (p. 33). The woman’s appearance further shames the Village – “We know we ought to make amends for shearing her” (p. 46) – and this brings the festivities to an abrupt end. Thereafter “Mistress Beldam” does indeed seem to be a sorceress, bringing havoc to the Village, and its abandonment, and the novel reaches its own climax in death and retribution, apparently orchestrated by the woman.

Through the events that begin with the two fires on the morning after the harvest, Walter Thirsk the narrator becomes ever more the outsider. His outsider status has always been signaled by the way his brown hair stands out among the blond heads of the other men. Thirsk had come to the village with Master Kent, as his man, following Kent’s marriage that had brought him to the manor. After Kent allowed Walter to leave his service to marry Cecily, Walter remains loyal to him, sometimes speaking up for the Master among his own neighbours, and still performing various small tasks for Kent, whenever he was called. So Walter has always been both partly an insider and yet still an outsider in the village community. He has “moments . . . when I miss greater places – the market towns, the liberties of youth, the choices I had left behind” (p. 20), and he knows that “I’m not a product of these commons but just a visitor who’s stayed” and that his teasing neighbours’ “suspicion of anyone who was not born within these boundaries is unwavering” (p. 62). As it happens, Walt is not actually present at the most important events of the unfolding crisis. He has burnt his hand quite badly in trying to save Master Kent’s hay in the fire at the manor, and so stays at home while all his neighbours go to confront the newcomers. From this moment, Walt’s position as an outsider to the community seems to become more and more marked. He and Mr Quill are taken to be part of a conspiracy with the newcomers to the Village and against his neighbours:

They’re closing ranks already [Walter says] and I am not included, despite my dozen years of standing at their shoulders. Old friends avoid my eyes . . . It is their reminder that I am the master’s man before I am a villager . . . And I know their expressions well enough . . . to understand that these are dangerous times for me . . . [I]f there’s a name that should be whispered . . . that might conveniently connect a suspect with a crime or might divert suspicion from a native-born, better it is mine. (p. 144)

Sure enough, he comes to be treated as one of the new lord’s men and is beaten up by his neighbours. He is told by his closest friend among his neighbours: “Go back, where you belong” (p. 156). Through Walter, we experience the “othering” of outsiders in a community, a social process that has occurred through history. The way that Walter Thirsk is treated powerfully recalls the way migrants, or minorities, are treated in our own societies.4

The great Marxist critic, Raymond Williams, has written about the significance in English culture of the idea of “Old England” as an England of “organic community” (1961, Part 3, Chapter 4). This is the sort of

country community, most typically a village [that] is an epitome of direct relationships, of face-to-face contacts within which we can find and value the real substance of personal relationships. (Williams 1975, p. 203, cited in Tew 2018).

But, as Williams writes,

it is foolish and dangerous to exclude from the so-called organic society the penury, the petty tyranny, the diseases and mortality, the ignorance and frustrated intelligence which were also among its ingredients. (1961, p. 253)

Crace shares this darker perception, and as his readers, we experience the tensions that are inherent within village communities, between neighbours as well as between lord and peasant. He portrays very well the “petty tyranny” of village society. When the armed retainers of the new lord of the manor seize some village women, their neighbours protest and they claim “We’re the majority . . . we must be listened to.” But, Walter observes,

I hear the word petition. I could tell them . . . that numbers amount to nothing in such matters. Dissent is never counted, it is weighed. The master always weighs the most.” (p. 145)

Attitudes towards religion are also well portrayed in Harvest. The plot of land set aside for a church serves as a graveyard, but the construction of the building has never been started. Walter remarks:

We do not dare to say we count ourselves beyond the Kingdom of God. But certainly we do not press too closely to His bosom; rather we are at His fingertips. (p. 35)

Just as the crisis that started with the arrival of the squatters goes a stage further with the death of the older man who had been put into the pillory, the Village is alerted “with six blasts on a saddle horn” to the arrival of yet more outsiders. Unbeknown to the villagers – though Walt has learnt of it from Mr Quill, to whom he was giving assistance – Master Kent holds the manor through his wife Lucy, who died in childbirth. Since she did not give birth to a son, the manor will be inherited by a cousin – a man called Edmund Jordan. He is to be the new lord of the village, and he arrives at Manor House, accompanied by his steward, a groom, and three sidemen (armed retainers, who are, as soon becomes apparent, thugs). Walter remarks, “I think Master Jordan must have counted on something bigger and grander. Certainly, he was dressed for that” (p. 84), and Walter observes that there is very little in the way of luxury or opulence in Manor House. Master Kent has even broken what had been the only mirror in the Village, his wife’s, after her death.

Walter has eavesdropped on the first conversation between Edmund Jordan and Master Kent. Jordan is brisk and efficient and has little patience with Kent’s misgivings about the treatment of the squatters. Master Kent is too soft-hearted and his current problems follow from being too kind. The newcomers are nothing but vagabonds and should be treated as such: “There were graver, grander things to talk about . . . his plans for Progress and Prosperity” (p. 99). These are the plans of which Master Kent had spoken at the harvest feast, but whereas Kent promised a dream in which all in the Village would benefit, Jordan has only a scheme “for a tidier pattern of living hereabouts which would assure a profit for those – he means himself – who have the ‘foresight’.” Jordan goes on:

We should not deceive ourselves that in a modern world a common system such as ours which only benefits the commoners (and only in prolific years) could earn the admiration of more rational observers for whom “agriculture without coin” is absurd. (p. 100)

How often through the history of capitalism must such remarks have been made. It is just as a historian of deserted villages, Christopher Dyer, writes:

The desertion of villages was one of the side effects of the rise of individualism at the expense of communities, and the weakening of peasant cultivation in preparation for the large commercial farms of the agricultural revolution. (2010, p. 31)

Master Kent can remain in the Village, but Jordan will “remain in his great merchant house in his great market town and simply check the figures once in a while” (p. 100). The work of enclosure will go ahead very quickly:

Before first snow [Mr Baynham, Jordan’s steward] will have structured everywhere within these bounds with fences, dykes and walls . . . Likewise the commons will be cleared and privately enclosed . . . We’ll never need another plough. (p. 101)

At this point Master Kent interrupts, hesitantly, “We have a little short of sixty souls to feed hereabouts” – a concern that Jordan shrugs off, saying that economies will have to be made. There will not be enough jobs for all in the Village. But the church will be built, at last, and a priest will be employed, and the bell in the church steeple will “hurry everyone to work. Those few that can remain, that is” (pp. 101–2). Later Edmund Jordan “mentions Profit, Progress, Enterprise, as if they are his personal Muses. Ours has been a village of Enough, but he proposes it will be a settlement of More” (p. 184) – though not for all, of course.

Thereafter the abandonment of the village proceeds apace, hurried on by accusations of witchcraft against two of the women and the little girl who was the Gleaning Queen. Master Kent visits Walt, apparently in a state of shock after what he has had to witness. “I have the sense,” he says to Walt, “my cousin is taking pleasure from sowing these anxieties.” And sure enough, Walter observes an unusual quiet in the Village: “. . . our village fabric is unravelling. The harvested barley is uncared for. A sack has toppled, and spilt. No one is even seeing off the rats” (p. 167). Jordan’s groom is attacked. People begin to leave the Village. There is “grief and anger in the air [but] also jollity . . . They’re free at last, and filling up with hope with every step.” They will come to join “the restless, paler people of the towns” (p. 176). What happened in the Village was exceptionally violent, perhaps, but not unlike what has been reported by historians:

Depressed and quarrelsome communities were abandoned by their demoralised inhabitants, and newcomers were discouraged from taking their places. Lords and their agents took advantage of the decay to graze large flocks and herds, and eventually established an enclosed pasture. (Dyer 2010, p. 44)5

Harvest is a rich and powerful work that takes the reader to the heart of what is surely one of the great transformations of modern history, the agrarian transition and the disintegration of peasant society, as it was experienced, in this case, in England.

Notes

1 In this essay, I refer to the Kindle version of the first edition of the novel, published in London by Picador in 2013.

2 This is certainly the case at Wharram Percy, in Yorkshire – the most intensively studied of the deserted villages.

3 One historian described the open field system like this: “In most of the economically important parts of the country [England] the open field system was the usual method of cultivation . . . The normal type of settlement in these areas was a village community, consisting of a cluster of houses standing in the middle of its territory, the most important part of which was the arable land, divided into two or three or four great fields. In these fields the villagers held their land in scattered strips . . . The intermingling [of which] meant that cooperation in cultivation was essential . . . Cooperation was necessary for other means of livelihood, too. The quantity of hay which a villager might draw from the common meadows, the number of pigs and poultry which he might support in the woods and wastes round the village, were regulated by custom . . . ” (Myers 1952, p. 40). See also Neeson (1996).

4 For me, his story recalls the marginal status of the man in whose house I lived in a village in northern Tamil Nadu. In his case he had come, unusually, to live in his wife’s village. He had lived in the village for more than twelve years, and had brought up four sons there, but he remained very much an outsider in village affairs.

5 See also Dyer (1994).

References

| Dyer, Christopher (1994), “The English Medieval Village Community and its Decline,” Journal of British Studies, vol. 33, no. | |

| Dyer, Christopher (2010), “Villages in Crisis: Social Dislocation and Desertion, 1370–1520,” in Dyer and Jones (eds.), pp. 28–45. | |

| Dyer, Christopher, and Jones, Richard (2010) (eds.), Deserted Villages Revisited, vol. 3, University of Hertfordshire Press, Hatfield. | |

| Hussey, Stephen (1997), “‘The Last Survivor of an Ancient Race’: The Changing Face of Essex Gleaning,” The Agricultural History Review, vol. 45, no. | |

| Jones, Richard (2010), “Contrasting Patterns of Village and Hamlet Desertion in England,” in Dyer and Jones (eds.), pp. 8–27. | |

| Jordan, Justine (2013), “Harvest by Jim Crace – Review,” The Guardian, February 16, available at | |

| Myers, A. R. (1952), The Pelican History of England, Volume 4: England in the Late Middle Ages (1307–1536), Penguin Books, London. | |

| Neeson, Jeanette M. (1996), Commoners: Common Rights, Enclosure and Social Change in England, 1700–1820, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. | |

| Tew, Philip (2018), “Pastoral Negativities and the Dynamics of the Storyteller in Jim Crace’s Harvest,” in K. Shaw and K. Aughterson (eds.), Jim Crace: Into the Wilderness, Springer International Publishing, Cham, pp. 17–31. | |

| Williams, Raymond ([1958] 1961), Culture and Society 1780–1950, Penguin Books, Harmondsworth. | |

| Williams, Raymond (1975), The Country and the City, Paladin, London. |