ARCHIVE

Vol. 10, No. 2

JULY-DECEMBER, 2020

Editorials

Research Articles

Research Notes and Statistics

Review Articles

Agrarian Novels Series

Book Reviews

Methodology of Data Collection Unsuited to Changing Rural Reality:

A Study of Agricultural Wage Data in India

*Research Fellow, University of Tokyo, yoshiusami@gmail.com.

†Joint Director, Foundation for Agrarian Studies and PhD Student, BITS-Pilani, Hyderabad Campus, arindam@fas.org.in.

‡Professor, Economic Analysis Unit, Indian Statistical Institute, madhuraswaminathan@gmail.com.

Abstract: Technological change and the modernisation of agriculture in India have led to many changes in farming practices. The mechanisation of field operations such as ploughing and harvesting, for example, has not only changed total labour use in crop production but has led to changes in labour-hiring practices and in wage forms. There is a rise in labour arrangements that pay wages on a piece-rated basis rather than on a time-rated one. In this article, we examine the two major official sources of data on agricultural wages in India, Wage Rates in Rural India (WRRI) and Agricultural Wages in India (AWI), in the context of these changes in farming practices. In addition to reviewing published material, we conducted personal interviews with relevant officials at various agencies to understand the actual process of data collection. Village-level data from the archive of the Foundation for Agrarian Studies (FAS) are also examined to get a picture of the complexity of rural wage arrangements.

Keywords: Agricultural Wages in India, Wage Rates in Rural India, village study, farming practice, mechanisation, rural labour, wage rate, agriculture, rural, India

Introduction

This article reviews the two major official sources of data on agricultural wages in India, Wage Rates in Rural India (WRRI) and Agricultural Wages in India (AWI), in light of the rapid changes in farming practices taking place in the countryside.1 We review different aspects of these data sources, including concepts and definitions used, questionnaire design, choice of sample, instructions to investigators, and methods of aggregation. Our general conclusion is that, for a variety of reasons, the methodology adopted by AWI and WRRI must be revised to capture the complexity of rural wages.

Technological change and the modernisation of agriculture in India have led to many changes in farming practices. The mechanisation of field operations such as ploughing and harvesting, for example, has not only changed total labour use in crop production but has affected the demand for male and female labour (Dhar 2012; Duvvuru and Motkuri 2013; FAS 2020a; Niyati 2020). In large parts of India, land preparation is entirely done by machines, with a consequent decline in use of bullock labour. As labour-hiring practices change, so do wage forms and wage rates. Changes in agricultural technology and farming practices have led to changes in labour-hiring contracts, in the forms of wages (time and piece rates) and payments (that is, payments in cash, in kind, and both) for specific operations (Ramachandran 1990; Gidwani 2001; Dhar 2017).

While there is extensive and useful literature on official statistics on wages and wage rates,2 this literature does not fully address the question of whether official data are able to capture changes in labour-hiring practices and associated changes in wages and wage rates. This issue is the main subject of this article.

Method

To understand the methodology of data collection, in addition to studying the manuals and questionnaires used by different agencies, we conducted personal interviews with relevant officials at various agency headquarters, State and district offices, and source villages to find out the actual process of data collection.3 We also reviewed various reports, specifically, the Report of the Working Group chaired by T. S. Papola titled Revision of Categorization of Non-Agricultural Occupations for Collection of Wage Rates. To check the reliability of reported wages at the State level, we examined unit-level WRRI data collected by the Field Operation Division of the National Sample Survey Organisation (NSSO).

Lastly, to comprehend the ground-level reality, we examined data on wages from the archive of village studies collected by the Foundation for Agrarian Studies (FAS) under its Project on Agrarian Relations in India (PARI) and conducted follow-up visits to selected villages. The village-level data provide information on wage payments for season-wise crop operations for men and women separately, as well as details on forms of labour hire, forms of payment, and hours of work.

Wage Rates in Rural India (WRRI)

Historical Background

In 1974, the NSSO established the Technical Working Group on Rural Retail Prices to revise and update the series of consumer price index numbers for agricultural and rural labourers. It recommended collecting data on wage rates for a large set of occupations (from suitably selected sample villages in various States) so that a fairly representative picture of the wage situation could be available for the entire country on a monthly basis. Following the recommendations of this Working Group, from July 1986 onwards, data on wage rates for 11 agricultural and 7 non-agricultural occupations have been collected regularly, along with data on rural retail prices, from 600 sample villages spread over 20 States. In November 2013, the classification of occupations was expanded to 12 agricultural and 13 non-agricultural occupations, following the recommendations of the Papola Working Group, but the methodology of data collection on wages was not revised.

On the recommendation of the Governing Council of NSSO, from 1995–96, the Labour Bureau began compiling and publishing the data on a monthly basis in the Indian Labour Journal in April 1998.

Data Collection and Compilation

Information on wage rates is collected by the NSSO’s Field Operations Division from 600 sample villages spread over 66 National Sample Survey regions of 20 States by canvassing Block-5 of Schedule 3.01(R).4 Village-level functionaries such as the panchayat secretary, “progress assistant,” patwari, and other village or block officials serve as the primary informants. Data on normal working hours and prevailing wage rates in cash and in kind for the reported working hours are collected sex-wise for each of the 25 (earlier 18) selected occupations. Where wage rates are reported for a duration less than or exceeding normal working hours, they are first adjusted for an eight-hour working day. Payments in kind are converted into cash at prevailing local retail prices. Thereafter, data is thoroughly scrutinized, and discrepancies, if any, are referred back to the NSSO for clarification.

In the next stage, a simple arithmetic average of these normalised daily wage rates is calculated by occupation and sex for each State. Up to June 2000, average wage rates at the all-India level were derived by taking the simple average of State figures; since July 2000, the averages have been obtained by dividing the sum total of wages of all 20 States by the number of centres or villages from which data were collected. State-wise averages are restricted only to those occupations where the number of centres is five or more to avoid abnormal fluctuations and inconsistency in wages paid to different categories of workers on account of varying numbers of centres. However, to calculate all-India averages, all neglected centres are taken into account to arrive at the total number of centres at the all-India level.

The terms of reference of the Papola Working Group were to study how to better capture non-agricultural wages (GoI 2013, p. 16). As part of this remit, the Working Group also discussed the choice of villages. As D. N. Reddy noted in the proceedings of the Working Group:

Many of the newly emerging activities are often concentrated in some of the nodal villages which are also the result of improved transport and communication facilities. This raises a question of the choice of the sample villages. For instance, Chadepalli, as observed earlier, is a remote village with relatively less diversification and therefore many non-farm activities (not only the newly emerging one but also the traditional ones like carpenter or blacksmith) do not exist in the village. So, the investigator has to go to another village within the cluster in search of occupations which are not there in the sample village. Though it may be possible to select a cluster of sample village where all the diverse occupation/activities for which wage data are to be collected, it may be advisable to have sample villages which are nodal-villages that represent relatively large number of farm as well as non-farm activities. This is more important in the present context of rapid rural diversification. (ibid., p. 20)

In light of this discussion, the Papola Working Group suggested:

In due course of time, the data collection mechanism may be revamped in terms of the number of sample villages from which the wage rates are collected. In order to have better coverage and sufficient flexibility in sample allocation to get robust average wage estimates for each of the occupation-categories, quality issues must not be compromised. (ibid., p. 18)

To sum up, while we cannot confirm if the actual sampling of villages was changed according to the recommendations of the Papola Working Group, WRRI may have started taking a “nodal village within the cluster” for reporting of wages.

Reliability of the WRRI Data

To check the reliability of WRRI data, Das and Usami (2017) adjusted the reported wage rates to the standard working day (eight hours); calculated State-wise averages for month, year, and major occupations from unit-level NSSO data;5 and compared these with reported WRRI data.6 They observed that the calculated averages, in most cases, were not identical to the reported wage data. A State-wise examination of wage rates for ploughing, for instance, showed a substantial number of identical cases between the calculated means and reported wage rates in Gujarat, Haryana, Himachal Pradesh, Jammu and Kashmir, Manipur, Meghalaya, Rajasthan, and Tripura. In Andhra Pradesh, Assam, Bihar, Tamil Nadu, Uttar Pradesh, and West Bengal, there were only a few or no identical cases at all (ibid.). They argued that this may not indicate unreliability of WRRI data, as the difference could be an outcome of the Labour Bureau’s internal process of data verification.7

Secondly, the authors found cases in which WRRI data were reported even when the number of sample villages was less than five, going against the stated compilation methodology. Further, in some cases of observations for less than five villages, the same wage rates were repeated over two or three months. This could be attributed to the fact that “data are thoroughly scrutinized by the Labour Bureau, and discrepancies, if any, are referred to the NSSO for clarification” and adjusted accordingly (GoI 2014b, p. 27).

Following the recommendations of the Papola Working Group, a reclassification of occupations was done in November 2013, to capture changes in the occupational structure that had occurred in the rural labour market. There is, however, no official linking factor for the old and new wage series, making it difficult for researchers to compare both series.8

A related but unexplained issue is how the reclassification of occupations was implemented. The NSSO’s Prices and Wages in Rural India (PWRI) reported wage rates of occupations following the old classification in November and December 2013 and the new classification from January 2014 onwards. The WRRI, however, reported wage rates according to the new classification from November 2013 onwards. Table 1 shows the data discrepancy created as a result of this difference. It is unclear whether the NSSO collected two data sets – one with the old classification under PWRI and the other with new classification under WRRI for two months, November and December 2013 – or only reported data in the format of the old series.

Table 1 Wage rates in the NSSO’s Price and Wages in Rural India (PWRI) and in Wage Rates in Rural India (WRRI) reports, by sex and crop operation, October–December 2013 in rupees

| Sex | Operation | PWRI | WRRI | ||||

| October | November | December | October | November | December | ||

| Male | Sowing | 190.83 | 195.25 | 202.31 | 198.59 | ||

| Transplanting | 183.83 | 193.89 | 200.46 | 186.36 | |||

| Weeding | 177.72 | 182.14 | 189.89 | 178.31 | |||

| STW | 184.17* | 190.42* | 197.85* | 187.77* | 218.45 | 213.63 | |

| Female | Sowing | 152.23 | 159.52 | 161.64 | 154.3 | ||

| Transplanting | 183.83 | 193.89 | 200.46 | 164.51 | |||

| Weeding | 152.46 | 153.61 | 158.85 | 155.33 | |||

| STW | 153.55* | 158.74* | 161.86* | 158.05* | 175.45 | 177.36 | |

Notes: All wage rates are standardised to eight-hour working days; * = simple average of sowing, transplanting, and weeding operations (STW).

Source: GoI 2014b.

In Table 1, we show the actual reported wages for sowing, transplanting, and weeding in the PWRI report along with the average wage for the combined operations of sowing, transplanting, and weeding (STW) as compared to the average STW wages as reported in WRRI for the same month. For both men and women, the averages we calculated for November and December 2013 were much lower than the averages reported in WRRI.

The change in occupations is associated with a sudden jump in agricultural and non-agricultural wage rates in November 2013 that persisted for a year (Das and Usami 2017). We have argued that as this jump occurred across occupations, it may not be on account of reclassification alone (ibid.), but this requires further investigation.

Agricultural Wages in India (AWI)

Historical Background

AWI provides monthly district-level data on wages of various agricultural and non-agricultural operations and has been collected by the Directorate of Economics and Statistics (DES) since 1950–51. It is published in the journals Agricultural Situation in India (biannually) and Agricultural Wages in India annually.

Data on wage rates are collected on a monthly basis from one or two key informants (respondents) in selected villages or centres in districts across 21 States by State agencies and sent to the DES, Ministry of Agriculture for compilation. There have been no changes in the definition of wages or the reclassification of the operations. Furthermore, AWI is the only source of time-series data on monthly wages at the district and State levels (Rao 1972; Kurosaki and Usami 2016).9

AWI data has serious limitations, which have been noted in the literature (Rao 1972; Jose 1974; Ghanekar 1997; Himanshu 2005; Chavan and Bedamatta 2006; and Kurosaki and Usami 2016). These pertain to the concept and definition of wage, reporting agencies, choice of respondents, sample size, representation and selection of districts and centres, frequent changes in the sample villages, missing data, and time lag in publishing.

The most recent evaluation of AWI data was by Kurosaki and Usami (2016), who used fixed-effects regressions and three naive approaches to test for statistical significance and bias on account of missing data for the period from 2005–06 to 2009–10. We have revised and updated the AWI data series compiled in Kurosaki and Usami (2016) and use this revised series to examine changes in methodology between 1998–99 and 2017–18.10

We have created a unique four-stage data validation process through interviews and data checks: interviews at the DES, New Delhi; at the State-level office that compiled the data set; at the district-/taluk-level; and with respondents at the village level. For validation at the State, district/taluk, and village levels, we have chosen four States – Karnataka, West Bengal, Bihar, and Punjab.

Data Collection and Compilation

The DES of the Government of India (GoI) is the nodal agency for collecting data for the AWI series, but the data is collected by respective State government offices. Table 2 lists the various State-level collection agencies: DES in Bihar, Commissioner of Labour in Karnataka, Land Record Office in Madhya Pradesh, Directorate of Agriculture in West Bengal, and Economic & Statistical Organisation in Punjab. The actual data collection is left to untrained investigators or officials at the block level using a standard questionnaire. The primary investigators also vary by State and include patwaris, data-entry operators, contractual investigators, and circle inspectors.

Table 2 Data collection agency for AWI, by State, 2005–06 to 2017–18

| Agency | State |

| Directorate of Economics & Statistics | Kerala, Andhra Pradesh, Telangana, Rajasthan, Odisha, Assam, Bihar, and Jharkhand |

| Commissioner of Labour | Karnataka and Maharashtra |

| Land Record Office | Madhya Pradesh, Himachal Pradesh, and Chhattisgarh |

| Directorate of Agriculture | West Bengal and Gujarat |

| Department of Economic & Statistical Analysis | Haryana |

| Economic & Statistical Organisation | Punjab |

Source: Collected by authors from DES, GoI, New Delhi.

As per the standard proforma, collection and compilation of wage data in the AWI reports fall under three broad categories: agricultural/field labour, herdsman, and skilled non-agricultural labour. Regarding the former category, field labour covers ploughing, sowing, weeding, reaping, and harvesting operations. The AWI also collects wage rates for transplanting but only includes those for sowing in the final report. Andhra Pradesh, Jharkhand, Karnataka, and Maharashtra do not provide data by agricultural operation and report the data for the group (i.e., field labour) as a whole. Other agricultural labour includes digging wells, cleaning silt from water channels, watering, carrying loads, embarkation, tilling, and plucking.

Data on wage rates are collected on a monthly basis by the respective State agencies.11 The annual average wage rate is reported for each agricultural year, i.e., July to June. As noted earlier, reports are delayed by two to three years.

The fact of no homogeneity of sampling in the process of data collection across the country raises questions about the quality of data. In the AWI, sample selection is non-random in nature, and thus the actual selection has a significant impact on the representativeness of centres in the district as well as the quality of data. This may be one reason for the variations in missing data across crop operations, seasons, and districts and States observed by Kurosaki and Usami (2016). As per the methodology given in the AWI 2017–18 report,

One or more casual labourers and farmers are primary informants for collection of data on wage rates. Wherever the informants’ numbers are high, average of data is taken in to account. (GoI 2018, p. 301)

In practice, actual respondents vary by agency. For example, the Commissioner of Labour collects information from workers, whereas the Land Record Office collects it from farmers, usually the sarpanch or other rich farmers. Thus, information pertaining to wage rates could be either from the employer or employee, depending on the particular State agency that collects data. This leads to a kind of asymmetry, as an employer is likely to report a higher wage as compared to a worker.

Definition of Wages

As per the instructions given to States by the DES, a “wage” is expected to be the “most commonly current” wage in a given month for the selected centre. In addition, wages paid in kind (e.g., foodgrains, cooked food, tea, coffee) are collected separately, and later evaluated at local market prices. The concept of “most commonly current wage” was adopted in the first Quinquennial Wage Census of 1908 to replace the earlier collection of data on a range of wages (Reddy 1978). From 1950, the GoI adopted this concept without any changes or further clarification in the definition or method of collection.

Secondly, as per the 2017–18 AWI report, wage rates for agricultural occupations have been collected for various operations such as ploughing, sowing, transplanting, weeding, and harvesting or/and reaping or/and winnowing but are compiled under the categories of “ploughman,” “sower,” “weeder,” and “reaper/harvester” (GoI 2018). In other words, a sower is considered as performing the combined operations of sowing and transplanting12 and a reaper/harvester as performing harvesting, threshing, and winnowing operations. This categorisation of occupations/operations has been borrowed from the Quinquennial Census, 1921, notwithstanding structural changes in the labour market (Reddy 1978).

Selection of Districts and Centres

The AWI suggests that State governments collect wage rates for all districts or all agroecological regions. In practice, the State governments select districts, based on various factors including the availability of staff at the local level. The actual number of selected districts vary over time. The coverage of districts has improved in recent years: the AWI reported wage rates for various operations in 234 districts across 17 States in 2005–06, which increased to 322 districts in 2006–07, 338 in 2010–11, 370 in 2013–14, and 399 in 2016–17.

Further, as all selected districts did not report data regularly, the number of districts in the final report varies each year. In southern States, namely Kerala, Andhra Pradesh, and Tamil Nadu, coverage included all agroecological zones. In northern and eastern States, namely Madhya Pradesh, Bihar, Rajasthan, and Odisha, coverage was high and also included all agroecological zones. On the other hand, Maharashtra, from 2010–11 to 2016–17, reported wages for only one district (Ghanekar 1997). Uttar Pradesh reported wages for only 10–13 districts from 2005–06 to 2015–16; however, this recently increased to 58 districts in 2016–17. In Bihar, the number of districts decreased from 15 in 2005–06 to 9 in 2009–10 and then increased to 29 in 2011–12.

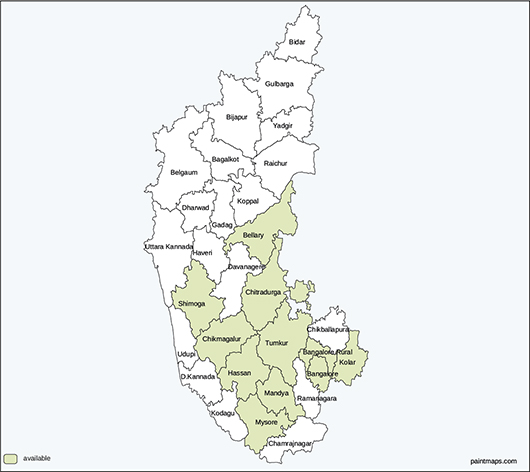

There is also variation in the distribution of centres across districts within at State. It appears that the low coverage in certain districts is on account of their being carved out of previously undivided districts. Newly formed or bifurcated districts were not included for data collection on wages by many States. In the case of Karnataka, from 1951–52 to 2016–17, the Labour Department has been collecting wage data for 10 districts, all of which belonged to the erstwhile State of Mysore (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Districts covered in AWI report, Karnataka, 2016–2017

Source: GoI (2019).

In addition, there is no instruction available for the selection of centres. As per the methodology given in the 2016–17 AWI report,

data on agricultural wage rates and skilled labour wage rates is collected once or twice in a month at the block level from one or two reporting villages and only average data of those collected twice or of two villages are reported to the district. (GoI 2020, p. 301)

The task of selecting centres is left either to the district or the State headquarters of the concerned agency.

It is important to note that the State authority collects wage data for the AWI along with other data. For example, the Labour Department of Karnataka collects different kinds of labour and wage data, and the Economic & Statistical Organisation of Punjab collects price and other data on State-level agricultural activities. Thus, choice of a centre in a given district depends on State-level data requirements rather than on the objectives of AWI. Furthermore, sample centres or villages in a district are not selected at random; it is doubtful that centres selected for obtaining wage rates are scientifically selected or replaced or based on cropping pattern, features of labour hiring, distance from town, or any other socio-economic factor. Rao (1972) noted that there was an upward bias of the AWI wages compared to other official data sources due to sample villages being chosen closer to urban areas. However, his argument does not hold for many States, and recent AWI data do not show any systematic upward bias in wage rates. Though the variability of wage rates within a district is narrowing over time, wage rates from different official databases are not strictly comparable at the district or State level.

Replacing centres and districts with new and non-reporting districts poses a serious methodological problem in the AWI data. It causes irregular fluctuations in the wage data when State-level time-series data on wages are constructed. The State-level data on centres show that, except for Kerala, Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, Punjab, and Haryana, changes in centres often takes place without any explanation. Since 2010–11, the replacement of centres with new ones has not been a regular phenomenon, with the exception of Rajasthan – this happened in 2014–15 when new centres replaced old ones in existing districts and new districts were added in Rajasthan.

Missing Data

One of the major problems with the AWI is that of missing data on various operations for some months and/or districts. Kurosaki and Usami (2016) observed two types of missing data: 1) data for all or several districts missing on a continuous basis and 2) data missing for specific farm operations.

On the first point, Kurosaki and Usami (2016) showed that the problem of missing data was comparatively small in Andhra Pradesh, Kerala, Madhya Pradesh, Haryana, and Odisha, whereas the extent of missing data or non-availability of data was significantly high in Assam, Bihar, West Bengal, Rajasthan, and Karnataka.13 Bihar, West Bengal, and Rajasthan continued to frequently report missing data without any improvement in the last 15 years.

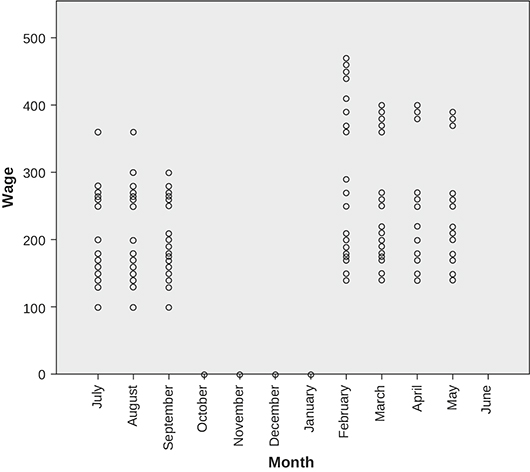

Missing data is serious for monthly wages disaggregated by agricultural operation. The main reason for this is, of course, that wage employment in agricultural operations depends on the crop, season, and farming practices. It is thus rare to find wage rates for all farm operations in every month. In Haryana, wage rates for all farm operations are not reported for October to January and again in June for all districts (Figure 2). Given the cropping pattern of the State, it is unrealistic that agricultural operations are performed in these months in all districts. Kurosaki and Usami (2016) noted that ploughing is either not reported in the peak season or reported for some months of a year and not reported in the next year.

Figure 2 Scatter plot of male wage rates for ploughing, sowing, weeding, and reaping/harvesting, Haryana, 2009–10 in rupees per day

Source: GoI (2014a).

We identify a third reason for missing data, namely, that data are misplaced or unpublished in the annual AWI report. Based on a visit to the Commissioner of Labour, Karnataka, we found discrepancies between data on wages that were collected and sent to DES and those actually published in the AWI report for Karnataka. For example, wage rates were collected every month in 2014–15 (for all districts except Bangalore rural), but the AWI report did not contain any data for three months (December, January, and February). The omission of data for these months in the published report could have been due to misplacement of data. In West Bengal, data were not published in the AWI reports for 2008–09 and 2009–10 but were available at the centre and district levels.14

To conclude, the AWI has been providing wage data since the 1950s, which are crucial for analysis of long-term change in the rural labour market. Though there have been efforts to improve the methodology, the fundamental problem is the lack of clarity in the definition of wages and the diversity of data collection agencies. The selection of districts and centres is non-random and changes over time, adding to the unreliability of data. In addition, the significant problem of missing data must be addressed by researchers interested in district-level analysis.

Variations in Rural Wages: Evidence from Village Studies and Implications for Official Data on Wage Rates

The diversity of forms of employment or labour hire in agriculture has been studied by many scholars, and as noted in Ramachandran (1990), “there is a wide variety of forms of labour, of institutional labour hire and of forms of remuneration in agriculture in south Asia” (p. 186). By forms of labour hire or employment, he refers to hiring of workers on an individual or institutional basis (such as in a group) for specific crop operations or groups of operations. He states,

These different forms of employment are characterised by different wage forms (various types of time-rates and piece-rates), by different forms of payment (cash wages, wages in kind, and wages in cash and kind), by various types of wage bargains, and by differences in the periodicity of employment contracts. (p. 189)

From 2005–06, the FAS has conducted 27 village surveys in different agroecological regions across 12 States. We draw on this archive of village-level data to bring to light the complexity of wages and wage payments in the contemporary period. We focus on ten villages from Karnataka, Bihar, West Bengal, and Punjab. Some features of the selected villages are shown in Appendix Table 1.

Drawing on these village surveys, we describe the diversity of labour hiring practices with a focus on changes in farming practices following mechanisation and complexity of sub-tasks within a given crop operation.

Form of Labour Hire

The data from the FAS archive shows a diversity of forms of labour hire in villages across the country, varying by village, crop, crop operation, gender, and technology or farming practices, among other factors.

For example, in villages in unirrigated regions, we found that for most field operations such as sowing; applying fertilizer; and harvesting of pulses, oilseeds, and fodder crops, labour was hired on a daily-rated basis. In Zhapur village (Kalaburagi district, Karnataka), workers were hired for harvesting sorghum and paddy on a daily-rated basis either in cash (Rs 100 for male and Rs 50 for female at 2008–09 prices) or in kind (4.5 kg of sorghum a day for males and females). In irrigated, rice-growing villages, it was common to hire labour on a piece-rated payment basis. In Hakamwala village (Mansa district, Punjab) and Panahar village (Bankura district, West Bengal), workers were hired in a group and paid on a piece-rated basis for paddy transplanting and harvesting, sugarcane harvesting, loading and unloading, and wheat harvesting and threshing operations. Here too, payments could be either in cash or as a share of produce (as in Amarsinghi village, Malda district, West Bengal). Female-only groups were observed in case of cotton picking and vegetable harvesting.

Forms of Remuneration/Wage Forms

There are two major wage forms: time-rated and piece-rated payments. Interestingly, the duration of employment and periodicity of payment can vary within each wage form. For example, both daily or casual labourers and long-term or attached labourers may be paid a time-rated wage despite working at different tasks and for different lengths of time. The daily-rated worker may be paid weekly, and the long-term worker may be paid monthly.

Among the nine villages, the share of labour hired on piece-rated payments ranged from zero to 76 (see Table 3). In two villages of Karnataka, there were no piece-rated payments. In Hakamwala village (Mansa district, Punjab), 76 per cent of hired labour was remunerated on a piece-rated basis.

Table 3 Proportion of total hired labour by form of wage, study villages, 2009–11 in per cent

| Village | State | Year | Share of hired labour in total labour use | Share of hired labour paid on time-rated wage | Share of hired labour paid on piece-rated wage |

| Tehang | Punjab | 2011 | 67 | 11 | 89 |

| Hakamwala | Punjab | 2011 | 59 | 24 | 76 |

| Katkuian | Bihar | 2012 | 74 | 41 | 59 |

| Nayanagar | Bihar | 2012 | 90 | 46 | 54 |

| Kalmandasguri | West Bengal | 2010 | 43 | 51 | 49 |

| Panahar | West Bengal | 2010 | 53 | 58 | 42 |

| Amarsinghi | West Bengal | 2010 | 55 | 60 | 40 |

| Alabujanahalli | Karnataka | 2009 | 54 | 69 | 31 |

| Zhapur | Karnataka | 2009 | 47 | 100 | 0 |

| Siresandra | Karnataka | 2009 | 51 | 100 | 0 |

Source: Dhar (2017).

Piece-rated payments were common for crop operations in the cultivation of paddy, wheat, sugarcane, and cotton, such as for transplanting paddy; weeding of paddy and sugarcane; and harvesting and post harvesting of paddy, wheat, sugarcane, and cotton. Such wage forms were extensively prevalent in the study villages of West Bengal. In Alabujanahalli village of Mandya district of Karnataka, transplanting of paddy, sowing of finger millet, and harvesting of sugarcane were completed by hired workers paid piece-rated wages. In Hakamwala village of Mansa district of Punjab, transplanting of paddy, spraying pesticides, and cotton picking was entirely done by groups, paid by piece rates. An important point to note and relevant for our discussion later is the coexistence of daily- and piece-rated wages for specific crop operations within a single village.

Piece-rated wages are calculated either on the basis of unit area/acreage or on the volume of production. For example, in Panahar village of Bankura district, West Bengal, piece-rated payments were common for transplanting and harvesting of paddy and packing potato. These wages were determined on a per acre basis, and the tasks were undertaken by a group of workers led by a labour contractor who mediated between landowners and workers. The groups generally comprised 10 to 20 workers, depending on the extent of land under contract. Furthermore, piece rates often varied by the size of the group, as a larger group could complete the task faster. For example, in 2009–10, the wage rate for paddy transplanting varied between Rs 700 and Rs 1000 per acre – the latter was for a group of four workers, who could complete 0.6 to 0.8 acres per day. For paddy harvesting, piece-rated wages were slightly higher at Rs 1,000–1,500 per acre. However, in Amarsinghi village of Malda district, West Bengal, harvesting and post-harvesting operations of paddy were undertaken on piece-rated payments by family groups (typically a couple), and wages were paid as a share of the harvest (that is, one fifth of harvested produce).

Variations Within Villages

Wage rates vary significantly within villages, even for the same operation, as shown in Table 5. For males, in all villages, the mean and median wage rate was generally less than the mode, suggesting that the distribution of wage rates was skewed to the left. For females, however, the mean and median were generally higher than the mode, suggesting that the distribution of wage rates is skewed to the right.

Table 5 Daily wage rates (cash + in kind), by operation (for the major crop) and sex, selected villages, 2008–12 in rupees

| Village | State | Operation | Female | Male | ||||

| Mean | Median | Mode | Mean | Median | Mode | |||

| Katkuian | Bihar | Sowing | 41 | 34 | 30 | 106 | 102 | 115 |

| Nayanagar | Bihar | Sowing | 55 | 57 | 60 | 84 | 96 | 100 |

| Alabujanahalli | Karnataka | Sowing | 62 | 64 | 56 | 137 | 139 | 139 |

| Amarsinghi | West Bengal | Transplanting | 89 | 93 | 94 | 89 | 93 | 114 |

| Weeding | 69 | 67 | 59 | 83 | 80 | 100 | ||

| Kalmandasguri | West Bengal | Transplanting | 79 | 78 | 70 | 99 | 100 | 100 |

Notes: All wages are at current prices (survey year) and not comparable across villages, and all wage rates are standardised to eight-hour working days. The data here are exclusively for operations that were paid on a daily rate.

In the next two sections, we highlight two specific issues that have not been addressed in the discussion of official data on rural wages: first, the implications of mechanisation and changing farming practices on certain crop operations and, secondly, wages for multiple sub-tasks within specified crop operations.

Changing Farming Practices

We focus on the implications of mechanisation on crop operations, taking the example of ploughing. Ploughing has traditionally been undertaken by human labour combined with animal labour (usually bullocks) but has increasingly shifted to machine-based ploughing with tractors.

Ploughing with Animal Labour

In Karnataka, ploughing with bullocks is still prevalent, and we observed the following labour-hiring arrangements:

When a landless labourer not owning bullocks is hired for ploughing by a bullock-owning employer, wages are paid in the form of time-rated payments to this labourer (a casual worker). In the two villages of Zhapur (Kalaburagi district) and Alabujanahalli (Mandya district), in 2008–09, wage rates for ploughing were Rs 100 for male workers, almost the same as wages for other daily-rated casual workers in agriculture.

Some large landowners may, of course, have a long-term worker who undertakes the task of ploughing. In this case, the wage is on a time-rated basis for an annual period.

It is common, however, for workers hired for ploughing to bring their own animals and be paid on a time-rated basis. For example, wage rates for ploughing with bullocks were Rs 400 per day in Zhapur and Alabujanahalli (2008–09). This wage is paid to a casual hired worker but is the combined payment for human and animal labour. The cost of animal labour includes the cost of fodder, maintenance, and depreciation. Thus, separating costs of animal labour from the total wage rate is complicated and could lead to errors in reporting the wage paid to human labour alone.

Payments to a worker for ploughing with own bullocks could also be in the form of piece-rate wages. We observed that payments for ploughing were Rs 600 per acre (for two ploughings) in all three villages of West Bengal (2009–10). This task includes ploughing and levelling of the fields. In this case, we could assume the worker to be an own-account worker receiving payments for his labour time and the cost of maintaining bullocks. The specific payment varied with the quality of land, number of ploughings, and distance of plot from the village.

Tractor-Based Ploughing

The use of tractors for ploughing is now widespread across the country and across all classes of cultivators on account of cost, convenience (saving time), and advantages such as deep ploughing. We discuss two cases of tractor ploughing:

Medium and large farmers owning tractors hire them out for ploughing. They usually hire out their tractors (using family members or attached labourers as drivers) on a piece-rated contract. When the tractor owners or their family members operate the machine, it is similar to the case of an own-account worker, and the payment for labour is usually higher than that paid to a worker hired as a tractor driver.15 In Panahar, in 2009–10, four households (out of 129 cultivating households) owned tractors. These households received Rs 480 to Rs 600 per hour as rent for the tractor, which included wages for labour and costs of tractor maintenance (diesel costs, maintenance, and depreciation).16

There are tractor owners with small or no landholdings whose main activity is renting out tractors for ploughing and other transport uses. In Nayanagar village of Bihar, a worker with marginal landholdings was able to save (from earnings received as a wage worker in Punjab) and buy a tractor and become a tractor driver, renting out his machine for ploughing and transport (of goods and people). For ploughing, he received Rs 450 to 700 per acre and was able to plough 6.5 acres in a day.

Crop Operations with Multiple Sub-Tasks

There are many field operations that have sub-tasks undertaken by different workers for different payments, making it difficult to interpret a single wage for a given operation. We illustrate this with the cases of transplanting and harvesting.

Transplanting

Transplanting involves multiple tasks: making bundles, transporting seedlings or saplings, and planting. Three types of labour-hiring arrangements for transplanting were observed in the villages studied:

Migrant workers were hired on a piece-rated payment basis. In the two villages of Punjab (Tehang of Jalandhar district and Hakamwala of Mansa district), typically, workers from Bihar, Uttar Pradesh, Jharkhand, and West Bengal were employed to undertake transplanting of rice.

In a small-farmer/peasant-dominated economy such as that of Amarsinghi village (Malda district, West Bengal), labourers were usually hired on a daily-rated basis to perform transplanting operations, usually alongside family labour.

In Panahar village (Bankura district, West Bengal), we found that transplanting was performed by a combination of labour-hiring practices, that is, hiring of casual, daily-rated workers as well as piece-rated workers, depending on the size of landholding. By our calculation, 44 per cent of hired labour was paid on a piece-rate basis.

In addition, and critical to this discussion, we observed a gender-differential in the sub-tasks of transplanting. In Panahar village (West Bengal), for example, male workers were hired for making bundles and paid a piece-rate of Rs 600 per acre, whereas female workers were hired for planting seedlings and paid Rs 500 per acre (in 2009–10). Thus, the wage payment varied by sub-task (and gender).

Harvest and Post-Harvest Operations

The big shift in harvest and post-harvest operations in large parts of the country is, of course, from manual to machine-based harvesting. This shift is associated with changes in labour hiring practices as well as in wage forms and is described in two cases below:

Manual harvesting of paddy is observed in West Bengal. We found both daily-hire arrangements (especially where members of peasant families also worked at the task) as well as hiring of workers on a piece-rated payment in Panahar and Kalmandasguri villages of West Bengal. Sub-tasks included cutting, threshing, winnowing, and packing, and each may have a separate labour-hire arrangement and need not be completed in a single day. In the case of piece-rated payments to a group of workers, the leader or contractor of the group may distribute the payment to all workers either equally or based on the tasks assigned. This was very common in Panahar and Kalmandasguri. When groups of workers were hired to complete a task, be it harvesting or transplanting, the workday usually exceeded eight hours. It becomes important to know the number of hours worked in order to normalise the wage payment to a standard eight-hour day.

Mechanical harvesting of wheat and paddy with combine harvesters started in the late 1970s in the north-western States and later spread to southern and eastern India. Today, combine harvesters (costing Rs 1,200,000–2,500,000) are operated across States (for example, the same machine and group of workers may harvest paddy in Punjab and Andhra Pradesh). The all-male harvest team usually comprises a driver, an assistant, and a few workers to assist in packing and transportation. In Tehang village (Jalandhar district, Punjab), 98 per cent of the paddy and wheat harvesting is by combine harvesters. A capitalist farmer owning a combine harvester rented his machine for paddy harvesting covering an average of 20 acres per day at the rate of Rs 850 per acre. In the case of wheat, the machine covered 30 acres a day, at a rate of Rs 900 per acre. The cost of diesel was three to four litres per day (incurred by the owner). The owner of the combine harvester hired a labour contractor/supervisor, paying him Rs 45,000 and Rs 50,000 for the paddy and wheat seasons, respectively; this covered payment for four workers – the contractor, driver, and two helpers.

Inadequacy of Official Wages Data in Relation to Rural Labour-Hiring Arrangements

The evidence presented in the previous section raises new questions about the methodology used by WRRI and AWI to address the complexities noted above.

First, we need to discuss the effects of changes in farming practices, as in the case of ploughing, on wage rates. Wage rates are likely to be the highest for own-account workers performing tractor ploughing, followed by own-account workers performing bullock ploughing, casual labourers ploughing with tractors, and casual labourers ploughing with bullocks. Thus, in any given location, the distribution of wage rates even for a specific operation (say ploughing) could be bimodal or multimodal on account of underlying differences in mechanisation. This raises questions about the use of summary statistical measures such as mean and median.17

It also makes it difficult to compare official series on wages rates across centres. Ploughing in Karnataka cannot be compared with that in Punjab, as the former may be for ploughing with bullocks and the latter for ploughing with tractors.

Further, as more regions of the country shift from ploughing with bullocks to the use of tractors, we cannot interpret long-term changes in wage rates for ploughing, even for a centre, district, or State.18

Secondly, it is not clear how sub-tasks within major field operations such as harvesting are accounted for when reporting the wage for a crop operation. The distribution of wage rates for a specific operation (e.g., transplanting) within a village was found to be skewed (see Table 5). This could be on account of differences in payment for sub-tasks of an operation that are not separately recorded in the data.

Thirdly, given the extensive prevalence of piece-rated payments, the conversion factor for arriving at a daily wage rate from a piece-rated wage is critical. The conversion factor would depend not only on hours of work but also on group size, payment to the group leader or contractor, and the specific operation. It appears there is no standard methodology to arrive at a conversion factor in the official data sources.

Issues with WRRI

The question of whether the methods of data collection on wages has kept up with the changing nature of farm operations and labour hiring at the ground level has been raised earlier. As a member of the Papola Working Group, A. V. Jose had raised this issue:

Ploughing, harvesting, threshing, and winnowing are some operations associated with traditional farming methods, now being replaced with the use of tractors and combine harvesters. Such changes (agricultural operation with modern machinery), under way in many parts of India, raise important questions about the changing mode of wage payment and gender composition of work force associated with modern mechanized farm operation. It looks as though in many rural centres there is a clear shift away from daily wages to the payment on piece rates for farm operations such as ploughing and harvesting, being carried out with farm machinery. (GoI 2013, p. 23)

Presently, wage data for WRRI are collected using the same Schedule 3.01 (R) from Block-5 as before. Even after the reclassification of occupations in November 2013, the questionnaire schedule continues to retain the same format and collects data on daily wage labourers, i.e., their normal hours of work and daily wage rates.

In WRRI, wage rates for ploughing operations are significantly higher than those for the combined operations of sowing, transplanting, and weeding and the combined operations of harvesting, winnowing, and threshing, and even higher than wage rates for masons in some States. However, we are not certain that WRRI collects wage rates for ploughing done either with own bullocks or tractors. The WRRI series separately provides wage rates for tractor drivers in non-agricultural activities.

We illustrate potential problems in recording of data in WRRI with the example of wage rates for ploughing in Punjab. Tractor ploughing is common in Punjab, as opposed to hiring a ploughman (with a pair of bullocks) on a daily wage basis. If we examine the number of villages reporting wage rates for ploughing and the number of months these villages reported wage rates in the WRRI for Punjab, not surprisingly, very few of the 15 sample villages reported wage rates for ploughing (Appendix Table 2). According to the unit-level data, the number of villages reporting wage rates for ploughing for the years 2001–02 to 2006–07 was generally less than four, and as a result, there were only one or two months with observations for five or more centres. The typical case was seen in 2003–04, when only two to four villages reported wage rates every month, and hence, no monthly average wage rates were calculated or reported in WRRI for 2003–04.

In 2009–10, however, the wage rate for ploughing was reported every month according to the WRRI, and in 2010–11, there were eight months in which wage rates were reported. This implies that five or more villages reported wage rates for ploughing every month in 2009–10. How did such a sudden change occur? It is uncertain if ploughing with a pair of bullocks was restarted in some of sample villages (unlikely), if the investigator looked for another village within the cluster, or if there was some imputation (or adjustment). Footnote 1 of Block-5 gives the piece-rate to daily-wage conversion for non-agricultural occupations such as carpentry and blacksmithery. This conversion rate could have been applied to ploughing as well. The wage rate for ploughing, therefore, could have been reported even in a village where “ploughing with a pair of bullocks” did not occur, assuming some parameters for human and animal labour.

In the case of tractor-based ploughing, particularly with an own-account worker rather than a tractor driver, the explanation reported in the official data sources is not sufficient to understand how exactly the “wage” was calculated and reported. It is highly unlikely that investigators collected information on all costs of tractor ploughing (such as diesel and maintenance) to identify the wage component. It is likely that investigators obtained the wage rate for tractor drivers or those employed in non-agricultural activities in the village/nearby villages and used it as the standard wage rate for ploughing (adding a premium/bonus for own-account workers or making a deduction for casual agricultural labour as the case may be). The State-wise correlation between wage rates for light motor vehicle/tractor drivers and ploughing labour, from the WRRI series, showed a positive relationship, with the exception of Assam, Karnataka, and Odisha.

On the question of the conversion of piece-rated wages to daily wage rates, as in the case of transplanting or harvesting operations, it is likely that the primary informants, based on their experience, guesstimated daily wage rates. If so, it is unlikely that WRRI correctly captures the equivalent daily wage rates for operations that were not actually performed by daily-rated wage labourers.

Issues in AWI

In terms of specific issues, first, as noted by many scholars, there is no elaboration of the term “most commonly current wage” (Rao 1972; Himanshu 2005; Chavan and Bedamatta 2006; Kurosaki and Usami 2016). According to the DES and taluk-level officials we interviewed, the “most commonly current wages” refer to the prevailing daily wage rates in cash and in kind that are reported for an eight-hour working day and collected separately for men, women, and children.

To understand how the AWI collects and reports the “most commonly current” or prevailing wage in a village, we visited the source village (Bhai Desa village, Boha centre) of AWI in Mansa district of Punjab in November 2019. Bhai Desa is 1 km off the State highway and 8 kms from Mansa. The primary crops in the village were rice, cotton, wheat, and potato. In addition, fodder crops, pulses, and oilseeds were cultivated as minor crops for household use. The purpose of the visit was to understand the method of data collection from the key respondent and the AWI investigator.

The first observation is that the sarpanch, who was the key informant in Bhai Desa village, told us that he had never met the AWI investigator. The AWI investigator was a data-entry operator (contractual staff) in the DES. He had said he collected information on wages every month from the sarpanch of Bhai Desa, but that he had not received any training with respect to collection of information on agricultural wages.

The sarpanch reported daily wage rates of Rs 250 in 2016–17 for male workers and Rs 300 in 2017–18 and 2018–19, which matches the data published in AWI. Apart from cash wages, workers also received in-kind payments (chapatis, cooked vegetables, tea, and, occasionally, alcohol). The investigator said that he did not collect information on the in-kind component of wage payments. Work hours were usually reported as eight hours. When we asked about wage forms, the respondent (sarpanch) told us that most of the operations were either done by groups of workers (usually migrant workers) paid on a piece-rated basis or by machines.

In Table 6, we have compared wage rates as reported by the sarpanch during our visit to Mansa village (November 2019) with those reported for the same operations in AWI (2017–18 and 2018–19) for the Bhai Desa centre.19 This comparison brings out various discrepancies. We were told that all ploughing was performed by self-owned tractors, but AWI has reported wage rates for ploughing. While all transplanting, we were told, was done by workers hired in a group, paid on a per acre piece-rate, AWI has converted the piece rate to a daily rate for an eight-hour day. In the case of harvesting, we found that it was done by machines and workers paid on a piece-rated basis – the AWI has converted piece rates to a daily wage rate.

Table 6 Wage rates collected through field visit and reported wage rates in Agricultural Wages in India (AWI) for Mansa village (Bhai Desa centre), by crop operation, 2017–18 in rupees

| Crop operation | Mansa (field visit) | Bhai Desa (AWI) |

| Ploughing | Nil* | 300–350/day |

| Transplanting (paddy) | 2000–2400/acre** | 350/day |

| Sowing (wheat) | Nil* | 300/day |

| Machine harvesting (paddy, wheat) | 1500/acre | 400–490/day |

| Manual harvesting (wheat) | 500/day | 490/day |

Notes: * = with own/borrowed machine; ** = group labour (piece rate varies with the variety of crop and the gap or spacing it requires).

Sources: Field visits and GoI (2018).

For ploughing, it is clear that wage rates vary depending on the ownership of implements and are generally higher than wage rates for other agricultural operations. The AWI collects data for casual labourers performing ploughing, the wage rates of which were found to be similar to or marginally higher than those for other field labour operations, with exceptions in Kerala, West Bengal, and Himachal Pradesh. This suggests that the wage reported in AWI is solely for human labour, excluding the cost of animal or machine labour. In cases of ploughing with bullocks, we expect wages to be higher than those reported for other field operations (e.g., weeding), as the payment includes the cost of animal labour. There is no clarity on how the AWI investigator estimates and excludes the cost of animal labour from total daily payments reported so as to arrive at the payment for human labour alone.20 Additionally, in case wage rates for either type of ploughing paid on piece-rated contracts, separating the payment for human labour from the cost of the machine or bullock is an even more complex task. As the form of labour-hiring arrangement (individual or group) and form of wage (time-rated or piece-rated payment) is not mentioned in the AWI methodology, it is not clear how wages for different types of ploughing have been calculated.

Given such changes on the ground, the “most common wage” for any operation could be payment to workers hired on a daily- or piece-rated payment basis (such as per unit of land or output). The latter requires a conversion factor or a definition of standard work norms per day to convert the piece-rated payment to a daily wage rate, taking working hours into account. The AWI does not collect data on working hours (as per the published questionnaire), with the exception of Kerala and, occasionally, Tamil Nadu. If the conversion is not done accurately, or not standardised across centres, there will be errors or biased estimations of the wage rates across centres and States.

Lastly, in a technical sense, “most commonly” prevalent wage may be interpreted as the modal wage rate. We have already noted that the distribution of wage rates may not be unimodal.

Concluding Remarks

Village-level data point to important changes in farming practices, resulting in new types of labour-hiring arrangements and associated wage forms. Mechanisation is extensive today, especially for ploughing and harvesting of food crops. The practice of hiring workers individually or in groups on piece-rated payments is also widespread. A further layer of complexity in wage payments arises from payments in kind and differential payments for sub-tasks. We argue that the methodology of data collection in the two major sources of official data on wages, Wage Rates in Rural India (WRRI) and Agricultural Wages in India (AWI), has not paid adequate attention to these changes, resulting in incorrect estimation of wage rates. In particular, there has been little or no change in sampling, concepts and definitions, questionnaire schedules, training, and other aspects of methodology, despite changes in farming practices. It is time to review and modify the process of data collection in official wage series so as to capture changes on the ground.

Acknowledgements: The research for this article was supported by the Azim Premji University Research Funding Programme, 2018. We are grateful to Amit Basole and other faculty members of the Centre for Sustainable Employment, Azim Premji University, for their comments and suggestions. We are indebted to various officers who met us, specifically B.L. Meena, Additional Economic Advisor, and Brijesh Prasad, Economic Officer, at the Directorate of Economic and Statistics, New Delhi, as well as officials of the Labour Bureau, Shimla, who facilitated interviews at various levels. We thank Rakesh K. Mahato and Ruthu C.A. for assistance with data processing.

Notes

1 This article draws heavily on FAS (2020b).

2 See, for instance, Rao 1972, Himanshu 2005, Chavan and Bedamatta 2006, Kurosaki and Usami 2016, and Das and Usami 2017.

3 For example, in Karnataka, we visited the Directorate of Economics and Statistics (DES), Department of Labour, and the University of Agricultural Sciences, Bengaluru. We acquired the AWI data collection methodology from the Department of Labour, Karnataka and interviewed the assistant labour commissioner and AWI investigator. We also visited the Labour Bureau in Shimla and Chandigarh and the DES, Punjab for official data on wages and interviewed the officials at different levels.

4 Data on wage rates are collected from 603 sample villages across 24 States in India, but during compilation, three villages from Delhi were excluded and four newly formed States (Chhattisgarh, Jharkhand, Uttarakhand, and Telangana) were merged with their respective erstwhile States (Madhya Pradesh, Bihar, Uttar Pradesh, and Andhra Pradesh).

6 It is noteworthy that working hours in north India were generally eight hours, whereas the working day was shorter in east and south India.

8 Das and Usami (2017) took the simple average of wages of the three separate operations of harvesting, threshing, and winnowing in the old series and linked it with the average of the combined wage for these operations in the new series. No similar correction was made for ploughing and tilling in the new series to compare it to ploughing in the old series.

9 Indeed, many scholars have used long time-series data at State or district levels to study changes in wage rates (see Jose 1974, 1988; Acharya 1989; Acharia and Papeniak 1995; and Chavan and Bedamatta 2006). Others (Jose 2017; Berg et al. 2012; and Acharya 2017) have used more recent data to observe changes in money and real wage rates.

11 The primary reporting agency is required to send the returns pertaining to a particular month on the second of the succeeding month to the concerned district. After scrutiny and consolidation, authorities at the district headquarters forward the data to State headquarters, which then sends the data to DES by the end of the second week of the succeeding month (GoI 2018, p. 331).

12 Wage rates for sowing and transplanting operations are collected separately but are reported jointly (GoI 2014a, 2020).

13 Between 2005–06 and 2010–11, there were numerous districts for which no wage data was reported. Between 2011–12 and 2017–18, there was a significant improvement in resolving missing data in the AWI reports.

15 Typically, a tractor driver was paid a wage of Rs 3000 per month and food. During the peak period when hours of work a day ranged from 10 to 16 hours, additional incentive payments were given.

17 Kurosaki and Usami (2016) also questioned the use summary statistics.

18 If wage rates for ploughing show a secular increase, we would need to separate the increase due to a shift from animal labour to tractor ploughing from that due to a pure increase in workers’ wages.

19 Provisional AWI report 2018–19 (GoI 2020), collected from Economic and Statistical Organisation, Government of Punjab and DES, GoI.

20 The Cost of Cultivation of Principal Crops reports provide a detailed methodology for calculating costs of animal labour and state that the calculation cannot be done in the field (GoI 2008).

References

| Acharya, Sarathi (1989), “Agricultural Wages in India: A Disaggregated Analysis,” Indian Journal of Agricultural Economics, vol. 44, no. 2, pp. 121–139. | |

| Acharya, Sarathi (2017), “Wages of Manual Workers in India: A Comparison Across States and Industries,” The Indian Journal of Labour Economics, September, vol. 60, no. 3, pp. 347–70. | |

| Acharya Sarathi, and Papanek, Gustav F. (1995), “Explaining Agricultural Wage Trends in India,” Development Policy Review, vol. 13, no. 1, pp. 23–39. | |

| Berg, Erlend, Bhattacharyya, Sambit, Durgam, Rajasekhar, and Ramachandra, Manjula (2012), “Can Rural Public Works Affect Agricultural Wages? Evidence from India,” CSAE Working Paper WPS/2012-05, Centre for the Study of African Economies, Department of Economics, University of Oxford. | |

| Chavan, Pallavi, and Bedamatta, Rajshree (2006), “Trends in Agricultural Wages in India 1964–65 to 1999–2000,” Economic and Political Weekly, vol. XLI, no. 38, pp. 4041–51. | |

| Das, Arindam, and Usami, Yoshifumi (2017), “Wage Rates in Rural India, 1998–99 to 2016–17,” Review of Agrarian Studies, vol. 7, no. 2, pp. 4–38. | |

| Dhar, Niladri Sekhar (2012), Employment and Earnings of Labour Households in Rural India: A Study of Andhra Pradesh, unpublished PhD thesis, University of Calcutta, Kolkata. | |

| Dhar, Niladri Sekhar with Patra, Subhajit (2017), “Labour in Small Farms: Evidence from Village Studies,” in Swaminathan, Madhura, and Baksi, Sandipan (eds.), How Do Small Farmers Fare? Evidence from Village Studies in India, Tulika Books, New Delhi, pp. 62–94. | |

| Duvvuru, Narasimha Reddy, and Motkuri, Venkatanarayana (2013), “Declining Labour Use in Agriculture: A Case of Rice Cultivation in Andhra Pradesh,” MPRA Paper 49204, University Library of Munich, Germany. | |

| Foundation for Agrarian Studies (FAS) (2015), “Calculation of Household Incomes – A Note on Methodology,” available at http://fas.org.in/wp-content/themes/zakat/pdf/Survey-method-tool/Calculation%20of%20Household%20Incomes%20-%20A%20Note%20on%20Methodology.pdf, viewed on August 24, 2020. | |

| Foundation for Agrarian Studies (FAS) (2020a), Current Labour Use in Crop Production and Potential Surplus Labour, Report submitted to the National Institute of Rural Development and Panchayati Raj (NIRD), Hyderabad. | |

| Foundation for Agrarian Studies (FAS) (2020b), Wage Rates in Rural India: Trends and Determinants, Report submitted to Azim Premji University Research Funding Programme, Bengaluru. | |

| Ghanekar, Jayanti (1997), “Sorry State of Agricultural Wage Data Sources and Methods of Collection,” Economic and Political Weekly, May 10, vol. 32, no. 19, pp. 1029–36. | |

| Gidwani, Vinay (2001), “The Culture Logic of Work: Explaining Labour Deployment and Piece-Rated Contract in Matar Taluka, Gujarat-Part 1 and 2,” Journal of Development Studies, vol. 38, no. 2, pp. 57–108. | |

| Government of India (GoI) (2008), “Manual of Cost of Cultivation Survey,” Central Statistical Organisation. | |

| Government of India (GoI) (2013), Report of Working Group for Revision of Categorization of Non-Agricultural Occupations for Collection of Wage Rates (Papola Working Group), Central Statistics Office, Economic Statistics Division, Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation. | |

| Government of India (GoI) (2014a), Price and Wages in Rural India (October 2013 to December 2013), National Sample Survey Office, Ministry of Statistics & Programme Implementation. | |

| Government of India (GoI) (2014b), Wage Rates in Rural India, Labour Bureau, Ministry of Labour and Employment. | |

| Government of India (GoI) (2018), Agricultural Wages in India, Directorate of Economics and Statistics (DES), Department of Agriculture and Cooperation, Ministry of Agriculture. | |

| Government of India (GoI) (2019), Agricultural Wages in India (2016-17), Directorate of Economics and Statistics (DES), Department of Agriculture and Cooperation, Ministry of Agriculture. | |

| Government of India (GoI) (2020), Agricultural Wages in India (2017-18), Directorate of Economics and Statistics (DES), Department of Agriculture and Cooperation, Ministry of Agriculture. | |

| Himanshu (2005), “Wages in Rural India: Sources, Trends and Comparability,” The Indian Journal of Labour Economics, vol. 48, no. 2, pp. 375–406. | |

| Jose, A.V. (1974), “Trends in Real Wage Rates of Agricultural Labourers,” Economic and Political Weekly, vol. IX, no. 13, pp. A25, A27–A30. | Jose, A. V. (2017), “Agricultural Wages in Indian States,” The Indian Journal of Labour Economics, vol. 60, no. 3, pp. 333–345. |

| Jose, A. V. (1988), “Agricultural Wages in India,” Economic and Political Weekly, Jun 25, pp. A46–58. | |

| Kurosaki, Takashi, and Usami, Yoshifumi (2016), “A Note on the Reliability of Agricultural Wage Data in India: Reconciliation of Monthly AWI Data for District-Level Analysis,” Review of Agrarian Studies, vol. 6, no. 1, pp. 6–38. | |

| Niyati, S. (2020), “Women in the Rice Economy of India: Evidence from Village Studies,” in Swaminathan, Madhura, Nagbhushan, Shruti, and Ramachandran, V. K. (eds.), Women and Work in Rural India, Tulika Books, New Delhi, pp. 109–133. | |

| Ramachandran, V. K. (1990), Wage Labour and Unfreedom in Agriculture: An Indian Case Study, Clarendon Press, Oxford. | |

| Rao, V. M. (1972), “Agricultural Wages in India: A Reliability Analysis,” The Indian Journal of Labour Economics, vol. 48, no. 3, July–September, pp. 89–116. | |

| Reddy, M. Atchi (1978), “Official Data on Agricultural Wages in the Madras Presidency from 1873,” The Indian Economic and Social History Review, vol. XV, no. 4, pp. 451–66. |

Appendices

Appendix Table 1 Agroecological features of 16 villages studied under the Project on Agrarian Relations in India (PARI), 2009–12

| Village | District | State | Survey year | Agroecological zone* | Agroecological features |

| Alabujanahalli | Mandya | Karnataka | 2009 | Southern Dry Zone | Canal irrigation; sugarcane, paddy, ragi, and sericulture |

| Siresandra | Kolar | Karnataka | 2009 | Eastern Dry Zone | Groundwater irrigation; ragi, vegetables, and sericulture |

| Zhapur | Kalaburagi | Karnataka | 2009 | North East Dry Zone | Unirrigated; millets, oilseeds, non-agricultural employment in stone quarries |

| Kalmandasguri | Cooch Behar | West Bengal | 2010 | Terai Zone | Unirrigated; paddy, jute, and potato |

| Amarsinghi | Malda | West Bengal | 2010 | New Alluvial Zone | Groundwater irrigation; aman/boro paddy and jute |

| Panahar | Bankura | West Bengal | 2010 | Old Alluvial Zone | Groundwater irrigation; aman/boro paddy, potato, and sesame |

| Tehang | Jalandhar | Punjab | 2011 | Northern Plain (Doaba region) | Groundwater irrigation; paddy, wheat, oilseeds, and fodder |

| Hakamwala | Mansa | Punjab | 2011 | Trans-Gangetic Plain (Malwa region) | Canal and groundwater irrigation; paddy, cotton, wheat, rapeseed, and fodder |

| Katkuian | West Champaran | Bihar | 2012 | North-West Alluvial Gangetic Region | Canal and groundwater irrigation; sugarcane, paddy, and wheat |

| Nayanagar | Samastipur | Bihar | 2012 | North-West Alluvial Gangetic Region | Groundwater irrigation; paddy, wheat, and maize |

Note: * = Agroecological zones are given as per the National Agricultural Research Project (NARP) classification.

Source: PARI village data.

Appendix Table 2 Villages reporting wage rates for ploughing in Wages Rates in Rural India (WRRI) by month, Punjab, 2001–02 to 2010–11 in number

| Year | July | Aug | Sept | Oct | Nov | Dec | Jan | Feb | March | April | May | June | No. of months with five centres | No. of months reported |

| 2001–02 | 2 | 5 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 2 | |||

| 2002–03 | 4 | 5 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 |

| 2003–04 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| 2004–05 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 6 | 6 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 2 |

| 2005–06 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 5 | 1 | 2 |

| 2006–07 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 1 | 1 |

| 2007–08 | 4 | 2 | 2 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 3 |

| 2008–09 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 |

| 2009–10 | 6 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 6 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 8 | 12 |

| 2010–11 | 9 | 5 | 6 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 7 | 7 | 8 |

Note: Data is available from July 2001 to June 2011, except October 2007 to December 2007 and July 2008 to June 2009.

Source: Author’s own calculation from PWRI unit-level data (GoI 2014a).