ARCHIVE

Vol. 11, No. 2

JULY-DECEMBER, 2021

Editorials

Research Articles

Research Notes and Statistics

Review Articles

Tribute

Public Policy and Human-Animal Conflicts:

Elephant Deaths in Kerala

*Professor, School of Development Studies, Tata Institute of Social Sciences, Mumbai rr@tiss.edu.

https://doi.org/10.25003/RAS.11.02.0008

Introduction

The unfortunate death, believed to have been caused by an explosion, of a female elephant in Kerala State, India, in May 2020 generated a national furore and a huge online response (Ellis-Petersen 2020), with people from across the social spectrum, including a number of celebrities, voicing their concern and sorrow at the tragedy. A petition calling for an official inquiry into the incident was signed by more than two million people worldwide (Al Jazeera 2020). However, media misreporting and social media-driven hearsay, plus the damaging and incorrect statements released by two senior Union ministers of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP)-led government, led to the issue acquiring a communal colour. Although the incident took place in Palakkad district, the false claim that it took place in Malappuram district soon gained currency. Right-wing Hindutva commentators linked the elephant’s death to the fact that it took place in a Muslim-majority district (Sikandar 2020). This prompted the Kerala Chief Minister Pinarayi Vijayan to step in, promising a proper investigation into the incident, but also deploring the “wrong priorities” of those who sought to “import bigotry into the narrative” (Sumit 2020).

The incident was officially described by Kerala’s Department of Forests and Wildlife as follows. On May 23, 2020, a female elephant with injuries in the mouth was spotted by forest officers at Ambalappara in the Mannarkkad forest division in Palakkad district. The elephant went back into the forest that day. On May 25, 2020, she was spotted again standing in the Velliyar river at a place called Theyyamkundu, outside the forest area. As is the usual practice, forest officers tried to drive the elephant back into the forest, but the animal refused to move. Veterinary doctors arrived and took stock of the case. Given her precarious health, they did not tranquilise her but rather decided that two kumki elephants (trained captive Asian elephants used to rescue trapped or injured wild elephants) be brought in to pull the animal out of the river. However, even before the kumki elephants arrived, the animal died. Post-mortem reports revealed that the elephant was two months pregnant.

False News

As mentioned earlier, false claims and narratives on social media gained considerable currency. Prakash Javadekar, then Union Minister for Environment, Forests and Climate Change, tweeted that the incident had happened in “Mallappuram [sic] district” of Kerala, and that it was “not an Indian culture to feed firecrackers and kill” (Sikandar 2020). The BJP leader and Member of Parliament, Maneka Gandhi embellished the falsehood further. “Malappuram is famous for such incidents,” she said, calling it “India’s most violent district.” She added that the police “should arrest everybody in Malappuram whom they suspect, because these are repeat offenders,” (Sikandar 2020).2

Secondly, there was no evidence – with the forest authorities or elsewhere -- for the assertion that the elephant was intentionally killed by feeding it a pineapple filled with firecrackers. The nature of the elephant’s injury indicated that it may have been caused by an explosive, but there was no information on when, where, or how the incident occurred. The case appears to have been an accident. A good guess is that the elephant may have consumed either a fruit or jaggery stuffed with crackers, which was meant as a bait for wild boars that raid the fields regularly. Sukumar (1994a) has provided details on such incidents in Tamil Nadu and Karnataka.

In fact, what was missing was a dispassionate discussion on the real issue that this incident brought to the fore, namely, problems of the human-animal interface, particularly in forest-fringe regions. Given all the finger-pointing and communal provocation, an opportunity to initiate a larger public discussion on this important public issue was lost.

The Facts

In her statements, Maneka Gandhi claimed that “over 600 elephants are killed in Kerala every year” or “every third day, an elephant is killed” (the arithmetic is as in the original) (Sikandar 2020). This is a fabrication. Let us first look at the official data of the Department of Forests and Wildlife. The Forest Department categorises the causes of wild elephant deaths into “natural” causes (old age, disease, infighting, predation, accidents) and “unnatural” causes (hunting, electrocution, vehicle-hits, explosives). The number of all “unnatural” deaths of wild elephants in Kerala was less than 10 a year (see Table 1). The only exception was 2015-16, when a single large poaching incident was uncovered near Malayattoor in Ernakulam district (Jacob 2016). Taking all the five years together, 93 per cent of the wild elephant deaths were “natural” deaths.

Table 1 Number of deaths of wild elephants in Kerala, in numbers and percentage, 2014-15 to 2018-19

| Year | Natural and other unknown deaths | Unnatural deaths | Total |

| 2014-15 | 100 | 3 | 103 |

| 2015-16 | 106 | 18 | 124 |

| 2016-17 | 117 | 9 | 126 |

| 2017-18 | 109 | 4 | 113 |

| 2018-19 | 110 | 10 | 120 |

| Total for 5 years | 542 | 44 | 586 |

| Share in total | 92.5 | 7.5 | 100.0 |

Note: Figures are provisional.

Source: Department of Forests and Wildlife, Government of Kerala.

Let us now disaggregate the figures for “unnatural” (see definition above) deaths (Table 2). Here again, 2015-16 was an exception, as mentioned above. Among all the unnatural deaths in 2016-17 and 2017-18, the deaths due to poaching and poisoning were insignificant, if not zero. Most of the unnatural deaths were due to electrocution or train accidents.3 Even when we consider all three years together, only about five per cent of elephant deaths in Kerala were due to poaching. If we exclude 2015-16 as an unusual year, the share falls to less than one per cent.

Table 2 Number of deaths of wild elephants in Kerala by cause, 2015-16 to 2017-18 in numbers and per cent

| Causes of death | 2015-16 | 2016-17 | 2017-18 | Total deaths in 3 years | Share in total (%) |

| Natural and unknown deaths | 106 | 117 | 109 | 332 | 91.5 |

| Electrocution | 1 | 5 | 4 | 10 | 2.8 |

| Train hit | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0.6 |

| Poaching | 16 | 2 | 0 | 18 | 5.0 |

| Poisoning | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0.3 |

| Total | 124 | 126 | 113 | 363 | 100.0 |

Note: Figures are provisional.

Source: Department of Forests and Wildlife, Government of Kerala.

Let us now consider a further disaggregation and a more recent period: the 12 months between January 1, 2019 and December 31, 2019 (see Table 3). In this period, there were 119 deaths of elephants in Kerala. Of them, the single poaching incident in 2019 was reported in Kollam district, an incident similar to that reported in Palakkad in May 2020. There were no cases of poisoning. Out of the eight electrocution deaths, six were accidental. There were seven deaths that were due to contagious diseases spread by domestic livestock, such as anthrax, foot and mouth disease, and rinderpest. Here again, natural causes, accidents, and accidental electrocution predominated in the causes of deaths.

Table 3 Number of deaths of wild elephants in Kerala, by detailed causes, 2019, in numbers

| Cause of death | Number of deaths |

| Poaching | 1 |

| Poisoning | 0 |

| Accidental electrocution | 6 |

| Deliberate electrocution | 2 |

| Train accidents | 4 |

| Road accidents | 1 |

| Contagious diseases | 7 |

| Declared rogue and killed | 0 |

| Other unnatural reasons | 6 |

| Natural reasons | 84 |

| Unknown reasons | 8 |

| Total | 119 |

Note: Figures are provisional.

Source: Department of Forests and Wildlife, Government of Kerala.

The Government of Kerala established a new classification of the causes of deaths of elephants in 2020 and 2021 (Table 4). Here again, the deaths that were due to natural causes were predominant; one case of hunting was reported each of two years, 2020 and 2021. In 2020, four out of the 114 elephant deaths were reported as caused by “explosives”; this included the elephant death in Palakkad discussed in this article.

Table 4 Number of deaths of wild elephants in Kerala, by new classification of causes, 2020 and 2021 in numbers

| Cause of death | Number of deaths, 2020 | Number of deaths, 2021 |

| Diseases | 20 | 15 |

| Electrocution | 3 | 6 |

| Hunting | 1 | 1 |

| Infighting | 13 | 12 |

| Natural causes | 19 | 38 |

| Natural accidents | 38 | 28 |

| Old age | 1 | 1 |

| Predation | 13 | 7 |

| Poisoning | 1 | 0 |

| Explosives | 4 | 0 |

| Total | 113 | 108 |

Source: Department of Forests and Wildlife, Government of Kerala.

Cruelty Towards Captive Elephants

In fact, from the point of view of animal welfare, a more serious problem in Kerala than poaching or poisoning is the extraordinary cruelty that captive elephants face (Bindumadhav, Sengupta and Mahbubani 2021). Most captive elephants are rented out for use at temple festivals across the State (Kuttoor 2012 and Iyer 2016). These festivals are held in the months between January and April-May. The elephants are made to walk on hot tar roads for long distances and for many days. They are paraded with caparisons at temple festivals, and denied adequate water, food, and sleep. These pressures cause many elephants to turn violent and run amok during temple processions, killing their mahouts and bystanders (Dalton 2018). While there have been media reports on cruelty towards elephants, there has been little public outrage over the continuing maltreatment and commercial exploitation of elephants.

Human-Animal Conflict

Human-animal conflicts have been the bane of life for people living and farming in areas close to forests (Rangarajan et al. 2010). A study by the Wildlife Institute of India (WII) estimated that between 2007 and 2011, there were 888 human deaths, 7,391 human injury cases and 14,144 livestock kill cases in India caused by human-animal conflict (Kuttoor 2017). About 80,900 cases of crop destruction caused by wild animals was also reported during this period.

More recent data indicate a rise in these conflicts and human deaths. In 2016-17, 2017-18 and 2018-19, there were 516, 501 and 494 human deaths, respectively, caused by elephants in India. Similarly, the number of human deaths caused by tigers were 62, 44 and 29, respectively, in 2016, 2017 and 2018. Elephants, thus, were responsible for the vast majority of human deaths caused by human-animal conflicts.

Kerala, with its eastern mountainous forest line running the length of the State, has a long history of migration and settled cultivation in the hills, an early spread of plantation agriculture, and a high population density. The State’s forest cover was 11,520 sq km, which covered about 29 per cent of its total geographical area, in 2019 (Government of Kerala 2020).

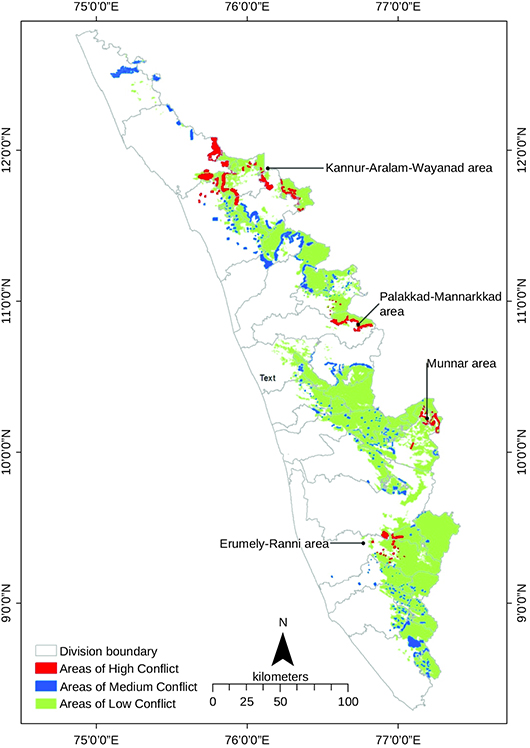

Kerala is thus a State prone to frequent attacks by wild animals in forest-fringe areas. Although almost all the forest divisions of the State are prone to human-animal conflict, the high-conflict areas are concentrated in northern Kerala (see Figure 1). A total of 10,095 human-wildlife incidents were reported in Kerala in 2020-21, a number more than three times greater than in 2009-10, when 2,922 such incidents were reported (Government of Kerala 2021). There were 319 human deaths caused by wildlife between 2009-10 and 2020-21 (ibid). Human deaths because of tigers or leopards were not reported after 2015, but several human deaths are reported every year in Kerala that are due to attacks by elephants. In 2021-22, there were 52 human deaths caused by wild animal attacks; of these, 25 deaths were caused by elephants (ibid). Tiger and leopard attcks were the cause of many deaths of domesticated animals such as goats, cows, buffaloes and poultry. These are apart from the hundreds of humans crippled and disabled by wild animal attacks (Jayson and Christopher 2008; Sengupta, Benoy and Radhakrishna 2020).

Figure 1 Major sites of human-animal conflict, Kerala, by intensity, 2020-21

Source: Government of Kerala (2021).

Apart from human deaths and injuries, large crop losses are reported in Kerala every year due to attacks of wild boar, porcupine, elephants, gaur, monkeys, wild pigs and deer (Veeramani, Easa and Jayson 2004). The maximum damage to crops reported are by of elephants, bonnet macaques and wild boars. About 45 species of edible and commercial plants are regularly destroyed by wild animals in the State. These plants include paddy, coconut, arecanut, rubber, banana, plantain, tapioca, sweet potato, coffee, oil palm, pepper, cardamom, ginger, jackfruit, mulberry, mango, and pineapple (Nair and Jayson 2021). Elephants are also responsible for considerable damage to physical property, such as cow sheds, irrigation structures, and huts.

Data with the Government of Kerala on compensation claims attest to the issues raised above. In the aggregate, the government received 10,095 applications for ex-gratia payments for multiple incidents related to compensation from wildlife attacks, and paid out Rs 8.5 crore as compensation (Government of Kerala 2021). In the same year, 2416 applications were received for ex-gratia payments related to the loss of human life and injuries to people, against which a payment of Rs 3.7 crore was made; in 2015-16, there were only 513 such applications. Similarly, 538 applications were received for ex-gratia payment related to loss of livestock against which a payment of Rs 72.3 lakhs was made; in 2015-16, there were only 355 such applications.

The large and increasing extent of losses incurred has indeed shaped the assertive and confrontational stances adopted by farmers against wild animals. It is in this setting that we need to view the larger issue of human-animal conflicts.

Traditional Control Measures

Kerala has a long history of settler-agriculture, staring from the 1930s. The population pressure on land, the crash of agricultural prices during the Great Depression, and conducive state policy encouraged thousands of farming households to migrate from the plains of central Kerala into the hills of the Western Ghats (Tharakan 1984). While land was freely available for clearing, cultivating, and settling in the Ghats, it brought the settlers and native Adivasis into close encounters with wild animals. According to an account of the period:

Their life was all the more hazardous as they were frequently attacked by wild animals. Their attempts to scare away the wild animals were not always successful. They had to risk their lives in their effort to protect their land and cultivation from the merciless attack of wild boars, elephants and tigers. There were instances of complete destruction of their cultivation by wild animals . . . Some of them, in their attempt to fight the wild beasts, escaped quite narrowly from the brink of death. Those dreadful life experiences, coupled with the untold miseries caused by epidemics like malaria, malnutrition and poverty, made their life an unending struggle between life and death (Sebastian 1986).

After the the 1930s, farmers settled near the forest areas set traps and took a range of defensive measures to protect their lives, farms, crops, and property (Jayson 2016). In addition to lethal control measures, farmers used several means to drive away wild animals. They hired workers to guard farms, installed scarecrows, dug trenches, constructed stone walls, bamboo fences, thorny bush fences or barbed wire fences, beat drums, or made sounds with metal objects, lit fires, burst firecrackers, or threw country bombs at night. They used stray dogs as guards, put up reed poles, placed bath soap in coconut shells at night, sprayed kerosene oil in the raiding paths of animals, or set baiting balls of jaggery, arecanut or wheat flour packed with poison or explosives. There were also official rewards announced for killing tigers and leopards.

These methods, over time and for many reasons, became ineffective against the attacks of wild animals. Though partially successful in reducing wild animal attacks, these measures were temporary in nature. For example, wild animals such elephants became used to most methods, and were not scared away by fire or loud sounds or other types of disturbance. Other methods were either very expensive, or led to collateral damage. Table 5 provides a summary of the methods used.

Table 5 An evaluation of traditional methods of crop protection from wild animals in Kerala

| Methods | Advantages | Disadvantages |

| Watchman (guarding at night from machans, huts on ground or rocks) | Immediate effect; can be used in combination with ordinary fencing | High wage costs; animals, mainly elephant and gaur, become used to the method; dangerous for watchers |

| Sound-making devices | Immediate effect; can be used in combination with ordinary fencing; inexpensive | Animals become used to the method |

| Lighting fires in the field using firewood, burning tyres or torches, and illumination with electric bulbs | Immediate effect; can be used in combination with ordinary fencing; inexpensive | Animals become used to the method |

| Olfactory (burnt chillies, toilet soap, smoke, repellents) | Immediate effect; can be used in combination with ordinary fencing; inexpensive | Animals become used to the method in a short time |

| Barriers (thorn fence, ropes, spikes, barbed wire, wooden poles) | Easy to construct; very effective against small mammals | Expensive; may cause injury to animals; not very effective against larger animals. |

| Missiles (spears, arrows) | Deterrent; not usually fatal to animals | Expensive; may injure animals; wounded animals become aggressive |

| Pet dogs | Alert the man on watch | Elephant may get aggressive; may chase dog and may turn out to be detrimental to man on watch |

| Unpalatable vegetation barriers (cacti, Hibiscus sp., eucalyptus etc) | Easy to grow; less expensive | Not effective against all animals |

| Stone wall | Little maintenance required | Limited effect; material not easily available; very expensive |

| Trenches | Very effective | High cost of construction and maintenance; elephant can refill ditch; not advisable in high rainfall areas with loose sandy soil |

Source: Veeramani, Easa and Jayson (2004).

Modern Approaches

The modern understanding of human-animal conflict is more scientific, comprehensive, and multi-dimensional than the “traditional” methods that we have described. The new approaches identify multiple causes for rising human-animal conflicts.

A starting point in the new approach to human-animal conflicts is the acceptance that it may never be possible to completely control or eliminate it (Nyhus 2016). Such conflicts have taken place for centuries and will continue. Another important element in the new approach is that it may be inappropriate to use the term “conflict” to describe the phenomenon, as it needlessly pits the habitat claims and requirements of humans and wild animals against each other. Hence, it is argued that future approaches should attempt at harmonising ecological systems in and near forests to reduce the human, animal, and economic losses that result from such encounters.

First, it is recognised that habitat fragmentation and natural resource depletion are major reasons for rising human-animal conflict (Sukumar 1994a). Over the years, forests have been depleted because of increases in population, urbanisation, industrialisation and infrastructure projects. As a result, animals like tigers and elephants, which have a home range of about 100 sq km and move long distances, frequently find their corridors obstructed and habitats fragmented. This leads to frequent forays by displaced animals into human habitations or cropped areas. Further, some studies show that the availability of water, fodder and forage inside the forests have dwindled, particularly in the summer months. This forces animals to roam longer distances and bigger areas in search of food and water.

Secondly, due to the success of various laws and conservation projects, the number of wild animals has increased (Gureja, Kumar and Saigal 2019). More important than population is the measure of density of animals (number per sq km), which has also risen in the case of tigers, elephants, and wild boars. In Kerala, which receives longer monsoons and has wetter forests than neighbouring States, wild animals also move in large numbers between January and May (Jayson 2016). Yet, this rising population must survive in the same extent of natural home ranges. In regions where the carrying capacity of the home range is exhausted, instances of wild animal invasions into habitations rise in frequency and intensity.

Thirdly, new work on wildlife behaviour show that most large mammals involved in human-animal conflicts are polygynous and show strong sexual dimorphism (Sukumar 1992). In elephants, the male animals have a larger body size and have secondary sexual signs like horns and tusks. There is also a strong selection for these characteristics among male elephants, as they enhance the ability of males to prevail over other males for females. This behavioural trait also brings the male elephant in close contact and conflict with people. Studies have shown that adult male elephants (or gangs of male elephants) enter cultivated areas six times more frequently and consume twice the quantity of crops than female elephants (Sukumar and Gadgil 1988). An adult male elephant causes considerably more economic loss than an adult female elephant. Similar results are reported for man-eating tigers in the Sundarbans.

Fourthly, research into optimal feeding habits of wild animals show that they feed in a manner that maximises the intake of energy, that is proteins and minerals, while minimising the time of consumption and effort in preying (Sukumar 1994a). This is one reason why tigers prefer domesticated cows to wild animals. Similarly, a raid on cultivated grasses like paddy fetches an elephant more protein, calcium, and sodium than wild grasses in the forest. To add to it, a drop in the protein content of wild food plants growing inside the forests has been noted by studies. Wild animals therefore tend to raid crop fields growing paddy, millet and maize with higher protein content (Sekhar 2013). In other words, frequent crop raids by elephants show a better foraging strategy shaped by evolution.

It is only by appreciating the importance of the spectrum of concerns, such as the ones discussed above, that we can think of comprehensive strategies to tackle human-animal conflicts. As a result, a combination of multiple strategies has come to be used by governments and farmers in the more recent years. They bring together the new understanding of wildlife behaviour and the use of new technologies.

Self-Defence Measures

To begin with, traditional methods like poison baits, explosive baits, the beating of drums, lighting night fires and employing night guards are still used in many regions, with varying degrees of success. However, as Table 5 shows, these are extremely cost, labour and time-intensive for farmers. They also expose farmers to direct confrontation with wild animals. Hence, new types of physical barriers are used, such as electric fences, solar power fences, elephant-proof walls, trenches, and early warning systems such as radio-collaring problematic elephants or using hidden cameras (Jayson 2016). Concrete structures and rail fences are also used in fencing. Of course, some of these permanent barriers are expensive, and need to be designed carefully to avoid damage to the ecosystems and fragmentation of habitats.

In many regions, new types of acoustic deterrents are used for self-defence, such as cattle recordings, alarms, bells, and electric sirens. Drones are also used to scare animals away. Finally, biological barriers are also used, such as beehives and chilli smoke. A better understanding of animal tastes has led farmers to use vegetative barriers also. The cultivation of a range of unpalatable crops can act as a buffer between the forests and the crop land. Thorny bushes and repellents like capsicum are also used as biological barriers.

Forest Management

Self-defence measures have to be integrated with better management of forests (Sukumar 2019). In recent years, forest departments have focused on increasing the availability of water and food inside the forests. For example, ponds are dug in the forests to help store water, particularly in summer. Elephant corridors are identified, and people are voluntarily relocated from nearby areas. In overly sensitive wildlife areas, vehicular traffic is banned or regulated. In extreme cases, translocation of problematic animals is adopted. Here, as research suggests, the focus is on translocating the leading male elephants in the raiding gangs.

Community Participation

Community participation by the local population has to be expanded and deepened. Rapid response teams have been formed by bringing together local youth, farmers and forest officials. For example, 204 jana jagratha samithi (People’s Vigilance Committee) units function in Kerala with people’s representatives, farmers’ representatives, and Forest Range Officers at the panchayat level (Government of Kerala 2021). Similarly, new forms of benefit-sharing in initiatives like eco-tourism, including the creation of a community fund, help boost confidence in local communities. Better compensation is assured for farmers who suffer crop losses (Government of Kerala 2017). While compensation addresses the effect and not the cause of wild animal attacks, they are nevertheless important in involving communities in the management efforts. Innovative insurance measures, designed to minimise moral hazard, are also being explored.

Land-Use Policy

The long-term success of efforts to reduce human-animal conflicts is crucially dependent on changing land-use patterns near forest areas (Nelson, Bidwell and Sillero-Zubiri 2003). Globally, the literature identifies four forms of such change:

In sum, a combination of all the measures we have discussed constitutes the modern approach to human-animal conflicts. At the government level, the human-animal interface is a multi-departmental concern. Flexibility must be ensured at the local level. Each location requires a customised solution and the choice of an appropriate technology; no blanket solution will be applicable for any large region. For example, it will not be desirable to choose elephant-proof walls everywhere as they are too expensive and will create barriers to the movements of cattle to graze and of people to enter the forests. Also, the behaviour of both humans and animals changes with the adoption of preventive measures. Hence, in the long run, there must occur a constant reinvention of methods, based on an improved understanding of wildlife ecology and animal behaviour, and more democratic participation of local communities.

Once appropriate methods are chosen, the Government of India must bear or share these costs at the national level. A national scheme to tackle human-animal conflicts, with freedom given to States to decide on the specific strategies, must be initiated and provided adequate funding. It is estimated that one km of an elephant-proof wall may cost close to Rs 1.5 crore.4 Similarly, the cost for a solar electric fence is about Rs 130,000 per km, and an elephant-proof trench would be about Rs 800,000 per km. For Kerala alone, the Department of Forest and Wildlife estimates that Rs 1150 crore would be required over five years for a series of activities – including physical and biological barriers, infrastructure, human resources, compensation, habitat improvement and training – aimed at reducing human-animal conflicts.

In short, the issue of human-animal conflicts requires careful multi-disciplinary study, deeper policy engagement, and more deployment of resources.

Notes

1 I have benefited from discussions with current and former forest officials with the Government of Kerala, particularly Anil Bharadwaj and Pramod G. Krishnan, and the comments of an anonymous referee.

2 As mentioned, the fact that Malappuram is a Muslim-majority district was used to link the “cruelty” against the elephant with religious belief.

3 Raman Sukumar (2020) points out that elephants are regularly killed in many Indian States because of “contact with overhead power transmission lines, injuries suffered when farmers retaliated, when elephants negotiated human-dominated areas, chewed on explosives kept inside food packets or fell into wells in agricultural fields.”

References

| See “Pregnant elephant’s death in India triggers ‘hate campaign,’”, Al Jazeera, 4 June 2020, available at https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2020/6/4/pregnant-elephants-death-in-india-triggers-hate-campaign, viewed on Jan 4, 2022. | |

| Bindumadhav, Sumanth, Sengupta, Alokparna and Mahbubani, Shilpa (2021), “The Effectiveness of Elephant Welfare Regulations in India,” in Eric Laws, Noel Scott, Xavier Font and John Koldowski (eds.), The Elephant Tourism Business, CABI International, London. | |

| Dalton, Jane, “Chained, beaten, whipped and exploited like slaves: The hidden horrors meted out to India's temple elephants,” Independent, April 21, 2018. | |

| See Ellis-Petersen, H., “Killing of elephant with explosive-laden fruit causes outrage in India,” The Guardian, 5 June 2020, available at https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/jun/05/killing-of-elephant-with-explosive-laden-fruit-causes-outrage-in-india, viewed on Jan 4, 2022. | |

| Government of Kerala (2017), Report of the Working Group on Forestry and Wildlife, Thirteenth Five-Year Plan 2017-2022, State Planning Board, Thiruvananthapuram. | |

| Government of Kerala (2020), Kerala Forest Statistics 2019, Thiruvananthapuram. | |

| Government of Kerala (2021), Report of the Working Group on Forestry and Wildlife, Fourteenth Five-Year Plan 2022-2027, State Planning Board, Thiruvananthapuram. | |

| Govind, S. K. and Jayson, E. A. (2018), “Crop Damage by Wild Animals in Thrissur District, Kerala, India,” in Sivaperuman C. and Venkataraman K. (eds.,) Indian Hotspots, Springer, Singapore. | |

| Gureja, Nidhi, Kumar, Ashok and Saigal, Suraj (2019), “Human-Wildlife Conflict in India,” Report prepared for National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan (NBSAP), New Delhi. | |

| Iyer, Sangita, “Gods in Shackles,” documentary film available at https://www.godsinshackles.com, viewed on January 4, 2022. | |

| Jayson, E. A. (2016), “Assessment of human-wildlife conflict and mitigation measures in Northern Kerala,” Final report of the Research Project KFRI/653/12, Kerala Forest Research Institute, Peechi. | |

| Jayson, E. A. and Christopher, G. (2008), “Human Elephant Conflict in the Southern Western Ghats: A Case Study from the Peppara Wildlife Sanctuary, Kerala, India,” Indian Forester, vol. 134 (10), pp. 1309-1325. | |

| Jacob, Jeemon “A Jumbo Nightmare,” India Today, October 13, 2016, available at https://bit.ly/3mywjXM, viewed on January 4, 2022. | |

| Krishnakumar, R. “Pointers to a negative growth rate,” Frontline, October 2, 2015, available at https://bit.ly/3swpdXO, viewed on January 4, 2022. | |

| Kuttoor, Radhakrishnan, “Cruelty against elephants,” The Hindu, February 15, 2012, available at https://bit.ly/3HcykRp, viewed on January 4, 2022. | |

| Kuttoor, Radhakrishnan, “Addressing the Human-Wildlife Conflict,” The Hindu, April 22, 2017, available at https://bit.ly/3sAAAOC, viewed on January 4, 2022. | |

| Nair, Riju P. and Jayson, E. A. (2021), “Estimation of economic loss and identifying the factors affecting the crop raiding behaviour of Asian elephant (Elephas maximus) in Nilambur part of the southern Western Ghats, Kerala, India,” Current Science, vol. 121 (4), August, pp. 521-528. | |

| Nelson, A., Bidwell, P. and Sillero-Zubiri, C. (2003), “A Review of Human-Elephant Conflict Management Strategies,” People and Wildlife Initiative, Wildlife Conservation Research Unit, Oxford University, Oxford. | |

| Nyhus, Philip J. (2016), “Human–Wildlife Conflict and Coexistence,” Annual Review of Environment and Resources, vol. 41 (1), pp. 143-171. | |

| Rangarajan, Mahesh et al. (2010), Gajah: Securing the Future for Elephants in India, The Report of the Elephant Task Force, Ministry of Environment and Forests, Ministry of Environment and Forests, New Delhi. | |

| Sebastian, P. T. (1986), “Problems of Peasant Settlers of Malabar,” Proceedings of the Indian History Congress, vol. 47 (1), pp. 671-679. | |

| Sekhar, T. (2013), “Dimensions of Human Wildlife Conflict in Tamil Nadu,” Indian Forester, vol 139 (10), pp. 922-931. | |

| Sengupta, A., Binoy, V.V. and Radhakrishna, S. (2020), “Human-Elephant Conflict in Kerala, India: A Rapid Appraisal Using Compensation Records,” Human Ecology, vol. 48, pp. 101–109. | |

| Sikander, Z., “Elephant or cow, Hindutva doesn’t give two hoots about animal welfare. Deaths are political,” The Print, 8 June 2020, available at https://theprint.in/opinion/elephant-cow-hindutva-give-two-hoots-about-animal-welfare-deaths-political/437520, viewed on January 4 2022. | |

| Sukumar, Raman (1992), The Asian Elephant: Ecology and Management, Cambridge University Press, New York. | |

| Sukumar, Raman (1994a), “Wildlife-Human Conflict in India: An Ecological and Social Perspective,” in Ramachandra Guha (ed.), Social Ecology, Oxford University Press, New Delhi, pp. 303-317. | |

| Sukumar, Raman (1994b), Elephant Days and Nights: Ten Years with the Indian Elephant, Oxford University Press, New Delhi. | |

| Sukumar, Raman (2019), “Conflicts between Wildlife and People: An Ecological, Social and Policy Perspective,” The Journal of Governance, vol. 18, pp. 154-160. | |

| Sukumar, Raman (2020), “Avoiding tragic elephant deaths through policy intervention,” Down to Earth, 11 August. | |

| Sukumar, Raman and Gadgil, Madhav (1988), “Male-female Differences in Foraging on Crops by Asian Elephants,” Animal Behaviour, vol. 36 (4), pp. 1233–1235. | |

| Sumit, U. “Tragic Death Of Pregnant Elephant In Kerala Fuels Bigotry, Disinformation,” Boom, 4 June 2020, available at https://www.boomlive.in/fake-news/tragic-death-of-pregnant-elephant-in-kerala-fuels-bigotry-disinformation-8373, viewed on January 4, 2022. | |

| Tharakan, Michael (1984), “Intra-regional Differences in Agrarian Systems and Internal Migration: A Case Study of Migration of Farmers from Travancore to Malabar, 1930-1950,” Working Paper No. 194, Centre for Development Studies, Thiruvananthapuram. | |

| Veeramani, A., Easa P. S. and Jayson, E. A. (2004), “Socio-economic Status of Cultivators and their Interface with Wild Animals: A Case Study of Marayur Forest Range, Kerala,” Indian Forester, vol. 130 (5), pp. 513-520. |

Date of submission of manuscript: April 4, 2021

Date of acceptance for publication: November 5, 2021