ARCHIVE

Vol. 3, No. 1

JANUARY-JUNE, 2013

Research Articles

Research Notes and Statistics

Review Articles

Tribute

Book Reviews

India’s Agricultural Debt Waiver Scheme, 2008

R. Ramakumar*

*Associate Professor, Tata Institute of Social Sciences, Mumbai, rr@tiss.edu.

An important policy intervention recently made by the Government of India in the sphere of rural credit is the Agricultural Debt Waiver and Debt Relief (ADWDR) Scheme of 2008. It is the first large-scale debt relief programme implemented by the government after 1990, when it had introduced the Agricultural and Rural Debt Relief (ARDR) Scheme.

The ADWDR Scheme was announced by Union Finance Minister P. Chidambaram in his Budget Speech for 2008–09 (GoI 2008). It was a response to reports, from the mid-1990s onwards, of acute agrarian distress in different parts of the country. Growth rates of agricultural production from the 1990s till the mid-2000s were lower than in the 1980s (see Ramakumar 2010). The low growth rates of these years were accompanied by an overall withdrawal of even the meagre institutional support structures in agriculture that the state had erected over the years. This withdrawal took place in many ways. First, the protection offered to many commodities from predatory imports was weakened in the period after 1995, when India joined the World Trade Organisation; this resulted in a fall in the output prices of these commodities. Secondly, as a part of the fiscal reforms, major input subsidies were brought down relative to the size of the agricultural economy; as a result, the costs of inputs such as seeds, fertilizers, electricity, and diesel rose rapidly. The rise in input costs was not compensated by increases in crop yields and output prices, and the minimum support prices administered by the government were not available to all farmers, particularly small and marginal farmers. Thirdly, public capital formation in agriculture continued to fall, and growth of public expenditure on research and extension slowed down. Most cultivator households ceased to have access to the agricultural extension machinery of the government, and thus to information on how to deal with pests and declining productivity of land. Farmers became dependent instead on agents of fertilizer and pesticide companies for advice on seeds and crop care. Finally, there was a weakening of the public credit provision system in the rural areas, and an increase in farmers’ dependence on loans from the informal sector to meet the costs of cultivation.

The spate of farmers’ suicides reported from many States after 1996 reflected the crisis in Indian agriculture: between 1997 and 2010, about 250,000 farmers committed suicide in rural India (see Nagaraj 2008; Sainath 2012). Apart from cultivators, agricultural labourers were also affected by the crisis by way of a drastic reduction in the number of days of employment available to them.

In 2007, the Government of India appointed an expert group, headed by R. Radhakrishna, to “suggest measures to provide relief to farmers across the country” (GoI 2007, p. 99). The expert group noted in its report that

There are many dimensions of the present agrarian crisis in India. The search for a solution therefore needs to be comprehensive by taking into consideration all the factors that contribute to the crisis. Furthermore, both short- and long-term measures are required to address the numerous problems associated with the agrarian crisis. Admittedly, farmers’ indebtedness, particularly due to growing borrowing from high cost informal sources, is one of the major manifestations of the crisis that needs to be addressed forthwith. In the short run, some concrete measures have to be taken up to reduce the debt burden of vulnerable sections of the peasantry. For this, the institutional arrangements for credit, extension, and marketing need to be revived. In the long run, a serious attempt has to be made to rejuvenate the agricultural sector with large investments in rural infrastructure, and in agricultural research and technology. The long-term credit needs of the farmers have to be augmented substantially to increase overall investment in agriculture (ibid., pp. 3–4, emphasis added).

In his Budget Speech of 2008–09, the Finance Minister opted for a full-fledged debt waiver scheme. The report of the expert group, he said,

had made a number of recommendations but stopped short of recommending waiver of agricultural loans. However, Government is conscious of the dimensions of the problem and is sensitive to the difficulties of the farming community, especially the small and marginal farmers. Having carefully weighed the pros and cons of debt waiver and having taken into account the resource position, I place before this House a scheme of debt waiver and debt relief for farmers. (GoI 2008)

The main features of the ADWDR scheme were the following:

- “Marginal farmers” (that is, farmers holding up to 1 hectare of land) and “small farmers” (holding between 1 and 2 hectares) would receive a full waiver of all loans overdue as on December 31, 2007 and outstanding as on February 29, 2009.

- All “other farmers” would be provided a one-time settlement, by which each borrower was eligible for a rebate of 25 per cent against payment of the balance 75 per cent.

- After the full waiver or the one-time settlement, farmers would be entitled to fresh agricultural loans from the banks.

Soon after the announcement of the loan waiver scheme, peasant organisations pointed out two major problems in its provisions. First, the scheme was likely to exclude a huge section of farmers in the dry regions of India, as the average size of land holding in these areas is above 5 acres per household. Secondly, the scheme ignored the needs of farmers who borrowed from the informal sector, and of agricultural labourers whose loans are not considered as crop loans.

The government refused to address the second problem but tried to partially address the first. It termed all districts of the country that came under the purview of the Drought Prone Area Programme (DPAP), Desert Development Programme (DDP), and the Prime Minister’s Special Relief Package of 2006 – that is, 237 out of India’s 537 districts – “dry and unirrigated districts.” In these 237 districts, it offered a one-time settlement of loans of either 25 per cent or Rs 20,000, whichever was higher.

When banks waived or settled loans, their loss was to be reimbursed by the government. As on March 2012, a total amount of Rs 52.52 billion (or Rs 52,520 crore) had been released to the eligible financial institutions by the government (Table 1). A large part of this (56 per cent) went to regional rural banks (RRBs) and cooperatives, and the remainder (44 per cent) to scheduled commercial banks (SCBs), urban cooperative banks (UCBs), and local area banks (LABs).

Table 1 Amounts reimbursed by the Central government to lending institutions as part of the debt waiver scheme, by instalment, as on March 2012 in Rs crore

| Instalments | Lending institution | ||

| RRBs and cooperatives | SCBs, UCBs, and LABs | Total | |

| 1st instalment, September 2008 | 17,500 | 7,500 | 25,000 |

| 2nd instalment, July 2009 | 10,500 | 4,500 | 15,000 |

| 3rd instalment, January 2011 | 1,240 | 10,100 | 11,340 |

| 4th instalment, November 2011 | 40 | 1,040 | 1,080 |

| 5th instalment, March 2012 | 0 | 100 | 100 |

| Total | 29,280 | 23,240 | 52,520 |

Notes: RRB = regional rural bank, SCB = scheduled commercial bank, UCB = urban cooperative bank, and LAB = local area bank.

Source: RBI (2012).

An adequate evaluation of the government’s debt waiver scheme is limited by the scarcity of disaggregated data. Kanz (2011) attempted to study the scheme with the help of data collected from a survey of 2,897 beneficiaries in Gujarat. He found that “debt relief does not improve the investment or productivity of beneficiary households, but leads to a strong and persistent shift of borrowing away from formal sector lenders” (p. 1). He argued that debt relief has major “reputational consequences” and encourages default with respect to future loans. Other commentators have similar views. Rath (2008) noted that while debt waiver would “bring some relief to many farmers,” the “long-term consequence” of the scheme would be “a gradual demise [driven by moral hazard] of the people’s own institutions like the cooperative credit societies and self-help groups” (p. 16). EPWRF (2008) commented that the debt waiver scheme “will go down in history as damaging the interests of the very small and marginal farmers that it has mainly sought to serve” (p. 28), and that

a socio-political environment that nurtures expectations of a loan waiver is not conducive for building a healthy financial system, particularly in rural areas where borrowers have weak bargaining power and bank officials are known to be reluctant to lend at the smallest sign of a poor recovery. (Ibid.)

Although it is clear that a loan waiver scheme is not sufficient to solve the problems of low rural incomes, inequality, and economic distress, it has the potential, I believe, to provide a measure of genuine relief. Nevertheless, even for supporters of the government’s loan waiver scheme, the design of the scheme is an important issue. Does it ensure that the benefits go to the worst-affected regions and classes of rural India? A response to that question is attempted in the sections that follow.

Exclusion of Informal Credit

The potential consequences of excluding loans taken from the informal sector from the loan waiver scheme are briefly illustrated below. In rural India, households with ownership of large holdings of land have better access to formal credit than households with small holdings. Even large farmers, however, borrow substantially from the informal sector.

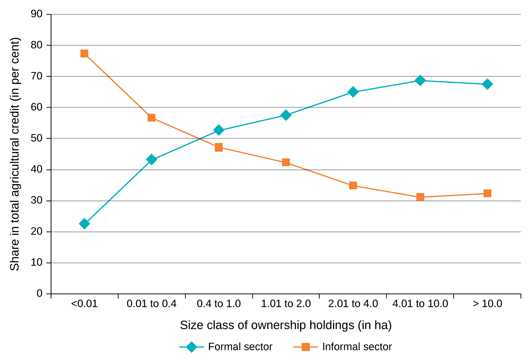

In 2003, according to the official data, the share of the formal sector in total debt outstanding among households with ownership holdings of land of less than 0.01 hectare was only 23 per cent. The corresponding figure for housholds with ownership holdings of 1 to 2 hectares was 58 per cent. In other words, even in the size-category of land holdings at the upper end of the group that is eligible for a loan waiver, that is, households with holdings of 1 to 2 hectares, the share of the formal sector in all outstanding debt was only 58 per cent.

Figure 1 Shares of outstanding debt of farmer households, of loans taken from formal and informal agencies, by size-class of ownership holding, India, 2003

Source: NSSO (2005).

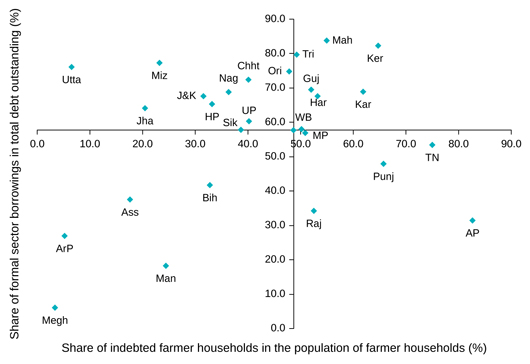

State-wise figures on the share of the formal sector in debt outstanding in 2003 provide more details in this regard. Table 2 is a two-way table that shows, by quartile and for different States, the amounts borrowed by farmers from the formal sector as a proportion of the total debt outstanding of all farmer households in the State (in the left-hand column), and the number of indebted farmer households as a proportion of all farmer households in the State (in the right-hand columns). In Figure 2, the first ratio described above is shown on the x-axis and the second ratio is shown on the y-axis, with the origin representing the all-India average in respect of each parameter.

As can be seen from Table 2, Maharashtra and Kerala were the only Indian States in 2003 that were in the top quartile in respect of both ratios. In States such as Tamil Nadu, Punjab, and Andhra Pradesh, the ratio of indebted farmers to all farmers was high, but the share of the formal sector in total amount outstanding was relatively low. The share of the formal sector in total debt outstanding was 53 per cent in Tamil Nadu, 48 per cent in Punjab, and just 31 per cent in Andhra Pradesh. At the same time, these States recorded some of the highest levels of indebtedness among farmer households: 75 per cent in Tamil Nadu, 65 per cent in Punjab, and 82 per cent in Andhra Pradesh. Andhra Pradesh also recorded one of the highest rates of farmers’ suicides in India between 1997 and 2010 (Nagaraj 2008). In other words, in States like Andhra Pradesh, Punjab, and Tamil Nadu, a large number of indebted farmer households are likely to have been left out of the debt waiver scheme when it was implemented.

Table 2 Formal sector loans and indebtedness among farmer housholds, State-wise, by quartile, India, 2003

| Value of loans taken by farmer households in a State from the formal sector as a proportion of total debt outstanding in that State among farmer households (%) | Farmer households that are in debt in a State as a proportion of all farmer households in that State (%) | |||

| Top 25% | Third 25% | Second 25% | Bottom 25% | |

| Top 25% | Maharashtra, Kerala | Tripura, Orissa | Mizoram, Uttarakhand | Chhattisgarh |

| Third 25% | Karnataka, Haryana | Gujarat | Nagaland, Jammu & Kashmir, Himachal Pradesh | Jharkhand |

| Second 25% | Tamil Nadu, Punjab | Uttar Pradesh, West Bengal, Madhya Pradesh | Sikkim, Bihar | – |

| Bottom 25% | Andhra Pradesh | Rajasthan | Manipur | Assam, Arunachal Pradesh, Meghalaya |

Source: NSSO (2005).

Figure 2 Number of indebted farmer households in a State as a proportion of all farmer households in that State (x-axis), and amount borrowed by farmers in a State from the formal sector as a proportion of the total debt outstanding in that State of all farmer households (y-axis), State-wise, India, 2003.

Note: The origin represents the all-India average.

Source: NSSO (2005).

Exclusion of Land Holdings Larger than 2 Hectares

About 22 per cent of all farmers who received a full waiver under the loan waiver scheme in India were from Andhra Pradesh, about 16 per cent from Uttar Pradesh, and 10 per cent from Maharashtra (see Table 3). In other words, about half of all farmers who received a full waiver under the scheme were from only three States of the Union.

Table 3 Beneficiaries who received full waiver under the loan waiver scheme as a proportion of all full-waiver beneficiaries in India, State-wise, in per cent

| State | (%) |

| Andhra Pradesh | 22.1 |

| Assam | 1.1 |

| Arunachal Pradesh | 0.0 |

| Bihar | 5.5 |

| Chhattisgarh | 1.6 |

| Gujarat | 1.9 |

| Haryana | 1.8 |

| Himachal Pradesh | 0.4 |

| Jammu & Kashmir | 0.2 |

| Jharkhand | 2.1 |

| Karnataka | 3.9 |

| Kerala | 4.6 |

| Madhya Pradesh | 5.7 |

| Maharashtra | 10.0 |

| Meghalaya | 0.1 |

| Mizoram | 0.1 |

| Manipur | 0.2 |

| Nagaland | 0.0 |

| Orissa | 7.9 |

| Punjab | 0.8 |

| Rajasthan | 3.7 |

| Sikkim | 0.0 |

| Tamil Nadu | 4.7 |

| Tripura | 0.2 |

| Uttar Pradesh | 15.9 |

| Uttarakhand | 0.5 |

| West Bengal | 4.8 |

| Total | 100.0 |

Source: Provisional figures received upon request from the Ministry of Finance, Government of India, New Delhi, September 15, 2012.

The number of beneficiaries in a State who received a full waiver as a proportion of all beneficiaries of the loan waiver scheme in that State serves as an indicator of the implementation of the scheme by the States. As is clear from Table 4, there were wide variations across States in the proportion of beneficiaries who received a full waiver.

Table 4 Beneficiaries in a State who received full waiver as a proportion of all beneficiaries of the loan waiver scheme in the State in per cent

| State | (%) |

| Andhra Pradesh | 85.7 |

| Assam | 94.6 |

| Arunachal Pradesh | 89.7 |

| Bihar | 94.6 |

| Chhattisgarh | 71.1 |

| Gujarat | 58.4 |

| Haryana | 59.6 |

| Himachal Pradesh | 96.0 |

| Jammu & Kashmir | 93.9 |

| Jharkhand | 95.9 |

| Karnataka | 67.8 |

| Kerala | 97.2 |

| Madhya Pradesh | 72.2 |

| Maharashtra | 71.2 |

| Meghalaya | 95.1 |

| Mizoram | 91.9 |

| Manipur | 97.6 |

| Nagaland | 84.6 |

| Orissa | 94.6 |

| Punjab | 54.0 |

| Rajasthan | 60.3 |

| Sikkim | 91.6 |

| Tamil Nadu | 81.3 |

| Tripura | 98.2 |

| Uttar Pradesh | 88.5 |

| Uttarakhand | 89.2 |

| West Bengal | 98.9 |

| Total | 81.6 |

Source: Provisional figures received upon request from the Ministry of Finance, Government of India, New Delhi, September 15, 2012.

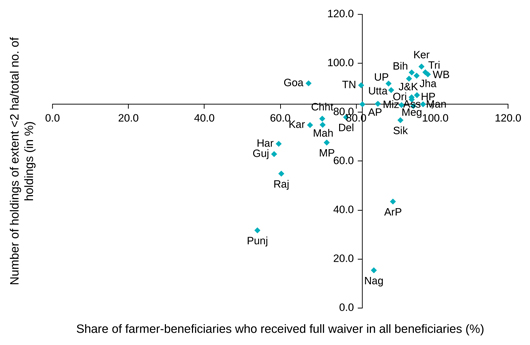

Table 5 is a two-way table that shows, by quartile and for different States, the number of beneficiaries in a State who received a full waiver under the loan waiver scheme as a proportion of all beneficiaries in the State, in 20121 and the number of household operational land holdings in a State of extent 2 hectares and below as a proportion of the total number of operational holdings in the State, in 2005–06. Here, I have considered the distribution of operational holdings as a proxy for the distribution of ownership holdings, as the Agricultural Census does not provide information on ownership holdings. In Figure 3, the first ratio mentioned above is plotted on the x-axis and the second ratio is plotted on the y-axis. The relevant figures on loan waiver were obtained from the Ministry of Finance, Government of India, and on land holdings from the Agricultural Census.

The salient features that emerge from the data are as follows.

- West Bengal, Kerala, and Tripura were among the best performers in respect of the number of loan waiver scheme beneficiaries who received a full waiver as a proportion of all beneficiaries: the shares were 98.9 per cent in West Bengal, 97.2 per cent in Kerala, and 98.2 per cent in Tripura. These States also recorded the highest shares in respect of the number of household operational holdings smaller than 2 hectares as a proportion of all operational holdings: 95.5 per cent in West Bengal, 98.7 per cent in Kerala, and 96.4 per cent in Tripura. In these three States, where the concentration of use of land holdings was low as a result of land reform, the benefits of the loan waiver were also better spread among small land holders than in other States.

- Although 91 per cent of household operational holdings in Tamil Nadu were smaller than 2 hectares, only 81 per cent of beneficiaries received a full waiver.

- More than 95 per cent of the beneficiaries received a full waiver in Kerala, West Bengal, and Tripura. The proportion of full-waiver beneficiaries was 71 per cent in Maharashtra and 72 per cent in Madhya Pradesh.

- Rajasthan, Haryana, Gujarat, and Punjab were among the States with the lowest proportion of full-waiver beneficiaries out of all beneficiaries.

Table 5 Beneficiaries of loan waiver scheme and size of household operational holdings, State-wise, by quartile, India

| Beneficiaries of loan waiver scheme who received a full waiver as a proportion of all beneficiaries of the scheme, 2012 (%) | Household operational holdings of less than 2 hectares in extent as a proportion of all household operational holdings, 2005–06 | |||

| First 25% | Second 25% | Third 25% | Last 25% | |

| First 25% | West Bengal, Tripura, Kerala, Jharkhand | Manipur, Himachal Pradesh | Meghalaya | – |

| Second 25% | Bihar, Jammu & Kashmir | Assam, Orissa | Mizoram, Sikkim | Arunachal Pradesh |

| Third 25% | Uttar Pradesh | Uttarakhand, Andhra Pradesh, Tamil Nadu | Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra | Nagaland |

| Last 25% | – | – | Chhattisgarh, Karnataka | Rajasthan, Haryana, Gujarat, Punjab |

Sources: Provisional figures as on September 15, 2012, received upon request from the Ministry of Finance, Government of India, New Delhi; Agricultural Census 2005–06, data downloaded from http://agcensus.dacnet.nic.in/statesummarytype.aspx, viewed on June 3, 2013.

Figure 3 Number of loan waiver scheme beneficiaries in a State who received a full waiver as a proportion of all beneficiaries in that State (x-axis), and number of operational holdings smaller than 2 hectares in a State as a proportion of the total number of operational holdings (y-axis), State-wise, India, 2005–06

Note: The origin represents all-India averages.

Sources: Provisional figures as on September 15, 2012, received upon request from the Ministry of Finance, Government of India, New Delhi; Agricultural Census 2005–06, data downloaded from http://agcensus.dacnet.nic.in/statesummarytype.aspx, viewed on June 3, 2013.

Conclusions

Three conclusions emerge from this brief study of the distribution of benefits from the government’s debt waiver scheme. First, farmer households that borrowed predominantly from the informal sector were excluded from the scheme. This exclusion, which was built into the scheme, was exacerbated in its implementation, as States with a high proportion of indebted farmers, such as Andhra Pradesh, Tamil Nadu, and Punjab, were also ones with a high share of informal sector loans in total credit outstanding. Secondly, in States where the share of farmer households operating more than 2 hectares was high, the share of farmer households that received a full loan waiver under the scheme was relatively low. Thirdly, the three States where there has been land reform – West Bengal, Tripura and Kerala – provided full loan waiver to almost all the beneficiaries of the scheme, and these beneficiaries were, as a result of land reform, almost entirely small and marginal farmers. Their performance stands in contrast to the records of States such as Maharashtra and Madhya Pradesh, where a relatively low proportion of the beneficiaries received a full waiver.

Acknowledgements: The author acknowledges the research support received from Biraj Swain and the Food Justice Campaign of Oxfam, and thanks V. K. Ramachandran for detailed comments on the article.

Notes

1 That is, those who received a full waiver plus those who received a one-time settlement. These data are from provisional figures received upon request from the Ministry of Finance, Government of India, New Delhi, September 15, 2012.

References

| Economic and Political Weekly Research Foundation (EPWRF) (2008), “The Loan Waiver Scheme,” Economic and Political Weekly, vol. 43, no. 11, March 15–21, pp. 28–34. | |

| Government of India (GoI) (2007), Report of the Expert Group on Agricultural Indebtedness, Banking Division, Department of Economic Affairs, Ministry of Finance, Government of India, New Delhi, July. | |

| Government of India (GoI) (2008), Union Budget Speech 2008–09, Ministry of Finance, Government of India, New Delhi, March. | |

| Kanz, Martin (2011), “What does Debt Relief do for Development? Evidence from a Large-Scale Policy Experiment,” The World Bank, Washington. | |

| Nagaraj, K. (2008), “Farmers’ Suicides in India: Magnitudes, Trends and Spatial Patterns,” Research Report, Madras Institute of Development Studies, Chennai. | |

| National Sample Survey Organisation (NSSO) (2005), Situation Assessment Survey of Farmers: Indebtedness of Farmer Households, NSS 59th Round, National Sample Survey Organisation, Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation, Government of India, New Delhi. | |

| Ramakumar, R. (2010), “Continuity and Change: Notes on Agriculture in ‘New India,’” in Da Costa, Anthony (ed.), A New India? Critical Perspectives in the Long Twentieth Century, Anthem Press, London. | |

| Rath, Nilakanta (2008), “Implications of the Loan Waiver for Rural Credit Institutions,” Economic and Political Weekly, vol. 43, no. 24, June 14–20, pp. 13–16. | |

| Reserve Bank of India (RBI) (2012), Annual Report 2011–12, Reserve Bank of India, Mumbai. | |

| Sainath, P. (2012), “Farm Suicides Rise in Maharashtra,” The Hindu, July 3. |