ARCHIVE

Vol. 13, No. 2

JULY-DECEMBER, 2023

Editorial

Research Articles

Tribute

Book Reviews

Review Article

Downturn in Wages in Rural India

*Joint Director, Foundation for Agrarian Studies, and Research Scholar, BITS-Pilani (Hyderabad Campus), arindam@fas.org.in.

†Associate Professor (retired), Osaka Prefecture University, yoshiusami@gmail.com

https://doi.org/10.25003/RAS.13.02.0002

Abstract: This paper uses two sources of data, Wage Rates in Rural India (WRRI) of the Labour Bureau and the Periodic Labour Force Survey of the National Statistical Organisation to examine trends in rural wages from 2014-15 to 2022-23. The WRRI data show a stagnation of real wage rates with an annual growth rate of less than one per cent for almost all agricultural and non-agricultural occupations. In contrast, PLFS data show an early post-pandemic recovery and rapid rise in earnings for rural casual workers in recent years. The discrepancy in growth of wages as between WRRI and PLFS, especially in the last three years, is not easily explained and suggests we remain cautious in using PLFS data without further validation.

Keywords: rural labour, wage rate, earnings, PLFS, WRRI, occupations, agriculture, construction, stagnation, pandemic

Introduction

This paper examines trends in wages for male and female casual workers in rural areas from 2014-15 to 2022-23, with a focus on changes in the post-pandemic period. The paper uses data from two sources to examine the pattern of change in rural wages of casual workers. The first source is Wage Rates in Rural India (WRRI), a monthly data series compiled and published by the Labour Bureau of the Government of India. The second source is the Periodic Labour Force Survey (PLFS) for the period 2017-18 to 2022-23.

WRRI is the most reliable official data source on wage rates for various agricultural and non-agricultural occupations and is available on a monthly basis for 20 States of India (Usami 2011, Das and Usami 2017, and Usami et al. 2020). Wage rates, along with rural retail prices, are collected by the NSSO’s Field Operations Division from a fixed set of 600 sample villages spread over 66 National Sample Survey (NSS) regions in 20 States. In the past, we have tested the reliability of WRRI data and found that WRRI data is comprehensive and reliable (Das and Usami 2017 and Usami et al. 2020).

Using WRRI data, our earlier work covered the period from 1998-99 to 2016-17. This article revises and updates the agricultural and rural labour wage series compiled by Das and Usami (2017).

Here is a summary of our previous work. After a period of long stagnation, rural wage rates for men and women across occupations rose at a significant rate from 2006-7 up to 2014-15. The growth rate for wage rates of all major agricultural occupations and unskilled non-agricultural occupations was more than 6 per cent per annum, while wage rates for non-agricultural skilled workers (carpenters, masons and blacksmiths) grew by around 5 per cent per annum at the all-India level. There are two distinct features of this period. First, the growth rate of wages for unskilled agricultural and non-agricultural workers was higher than for skilled non-agricultural workers. Secondly, wage rates of women workers grew faster than wage rates of male workers for various agricultural occupations, leading to a narrowing of the gender wage gap nationally.

The rising trends in real wage rates for casual workers in rural areas after 2007 has been widely discussed in the literature (Himanshu and Kundu 2016, Himanshu 2017, Kundu 2019). Explanations put forward for this pattern of wage growth include a rise in agricultural productivity, stable agricultural prices (in particular, the payment of Minimum Support Prices or MSP), the implementation of MGNREGS, revision of minimum wages, growth in the construction sector, and a stable rise in NSDP (Berg et al. 2012, Gulati, Jain, and Satija 2013, Jose 2013, Himanshu and Kundu 2016, and Himanshu 2017). Further, MGNREGS may have had a greater influence on female agricultural wage rates than on male wage rates in rural India (Chandrasekhar and Ghosh 2011, and Azam 2012), resulting in the observed pattern of wage growth.

In this paper, we ask what happened to wage growth in the last nine years, 2014-15 to 2022-23. Das and Usami (2017) and Himanshu (2017) showed that real wage growth began to decelerate in 2013-14. Kundu (2019) and RAS (2019) showed a clear deceleration in the growth of real wages between 2014 and 2019. Using data on selected rural farm and non-farm occupations from Wage Rates in Rural India, Dreze (2023a and 2023b) concluded that the growth of real wage rates in rural areas was less than one per cent between 2014-15 and 2022-23, and further decelerated in the post-pandemic period. Bhalla (2023), however, claims that wages grew more rapidly. Using data from PLFS data, Arora (2023) and Menon (2023) argue that wage rates rose in the post-pandemic period among casual labourers. These divergent findings led us to further study the pattern of growth of real wages in recent years.

Evidence From Wage Rates in Rural India (WRRI)

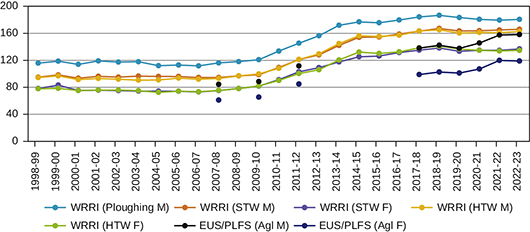

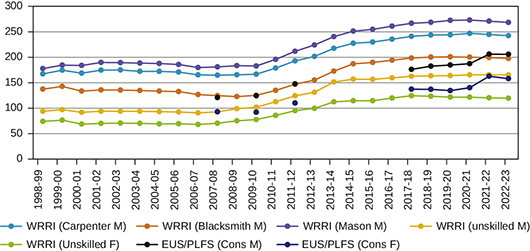

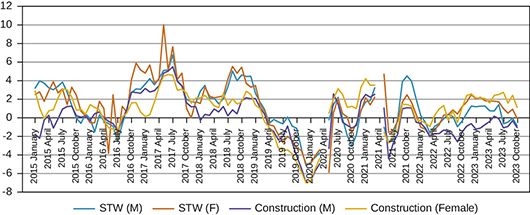

The methodology used in WRRI has been discussed in detail in Das and Usami (2017). Using the same methodology, we have updated the wage series and examined trends in real wage rates at the all-India level for three agricultural occupations, ploughing (by men), sowing/transplanting/weeding or STW, male and female, harvesting/threshing/winnowing or HTW, male and female (Figure 1). In Figure 2, we examine trends in wage rates for five non-agricultural occupations at the all-India level, namely carpenters (male), blacksmiths (male), masons (male) and unskilled non-agricultural workers (male and female). Although we have plotted wage data for the last 25 years, our focus is on trends and patterns of growth in wage rates in rural areas from 2014-15 to 2022-23. To arrive at the annual wage series for each occupation, nominal wages were computed for the agricultural year (July to June). The Consumer Price Index for Agricultural Labourers (CPI-AL) and the Consumer Price Index for Rural Labourers (CPI-RL) were used as deflators for agricultural occupations and non-agricultural occupations, respectively. Real wage rates are expressed at 2009-10 prices. The year-on-year (Y-o-Y) change in wage rates over the previous year for selected occupations at the all-India level, from January 2015 to October 2023, are shown in Figure 3.

Figure 1 Real wage rates for various agricultural occupations, 1998–99 to 2022-23 in Rupees

Note: STW=sowing/transplanting/weeding, HTW= harvesting/threshing/winnowing, Agl= agricultural worker, M=male, F=female.

Source: Labour Bureau and NSO, various years, and Das and Usami (2017).

Figure 2 Real wage rates for various non-agricultural occupations, 1998–99 to 2022-23 in Rupees

Note: Unskilled labour refers to non-agricultural workers, including porters and loaders, M=male, and F=female.

Source: Labour Bureau and NSO, various years, and Das and Usami (2017).

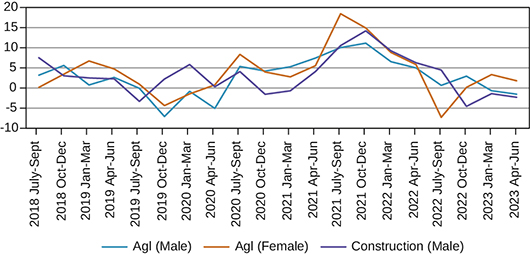

Figure 3 Year-on-year changes in rural wage rates, India, January 2015–October 2023 in per cent

Note: STW=sowing/transplanting/weeding, M=male, and F=female

Source: Labour Bureau, various years.

Three important patterns emerge. First, the growth of wage rates began in 2006-07, right after the implementation of MGNREGS, and accelerated after 2009-10. A gradual decline began in January 2013 and continued until October 2013 (Das and Usami 2017). A sudden jump took place in November 2013 at a time when the Labour Bureau reclassified occupations (Das and Usami 2017), and the wage level continued to increase for one year. The reason for the unexpected jump in real wages is still unclear. This was most likely due to the reclassification of agricultural tasks. The trend in wage rates was rising up to 2014-15 on account of the unexpected jump in real wage rates in November 2013. Otherwise, the rapid rise in real wages terminated in 2012-13. Because of the reclassification of occupations, the new series (after November 2013) and the old series are not strictly comparable. In the following sections, therefore, growth rates are estimated from 2014-15 to 2022-23.

Secondly, from 2014-15, real wage rates for agricultural and non-agricultural occupations were stagnant or declined up to 2022-23. Annual fluctuations in the trends also occurred. In 2015-16, there was an absolute decline in agricultural wages (Figure 3). The absolute decline may have been on account of back-to-back droughts in 2014 and 2015 (Himanshu 2019). The Gross Value Added (GVA) from agriculture, forestry and fishing declined in 2014-15 and 2015-16 (Figure 6). There was a revival in 2016–17 and 2017-18. The pace of recovery in real wage rates does not seem to have been affected by demonetisation or the introduction of GST. Overall, wage rates for major rural occupations grew at less than 2 per cent per annum from 2014–15 to 2018-19.

Thirdly, wage growth for major rural occupations turned negative in 2019-20 and remained so in 2020-21 and 2021-22. The Covid-19 pandemic affected wages significantly. During the pandemic, the decline in growth of wages was much faster for female agricultural labourers than for males. A slow recovery was observed in 2022-23. Between 2019-20 and 2022-23, the growth of real wages for all rural occupations were negative, ranging from (-)0.2 to (-)1.1 per cent per annum.

Overall, the growth of wage rates in rural areas virtually collapsed for all agricultural and non-agricultural occupations in the last nine years (from 2014-15 to 2022-23). In absolute terms, real wage rates for various agricultural occupations increased by less than ten to twelve rupees from 2014-15 to 2022-23. For example, the wage rate for ploughing increased by six rupees, from 176.90 in 2014-15 to Rs. 180.60 in 2022-23. For the same operation, real wage increased by sixty rupees from 2007-08 to 2014-15 (Rs. 116.10 to Rs. 176.60). A sharp deceleration in wage growth was also recorded in operations such as sowing/transplanting/weeding and harvesting/threshing/winnowing, where female participation is high. Women’s wage rates for sowing/transplanting/weeding rose from Rs. 125.10 to Rs. 136.90, and for harvesting/threshing/winnowing they rose from Rs. 132.10 to Rs. 134.60 between 2014-15 and 2022-23, that is, an increase of Rs. 12 and Rs. 2 respectively.

Similarly, wage rates for male skilled and unskilled non-agricultural occupations were almost stagnant in the last nine years, rising from Rs. 251.30 to Rs. 264.70 for masons, from Rs. 227.40 to Rs. 242.34 for carpenters, and from Rs. 181.20 to 186.50 for construction.

The WRRI data series provides information on wages for 23 occupations for male workers and 16 occupations for female workers. The all-India average annual growth rates of wages for all agricultural and non-agricultural occupations for the period 2014-15 to 2022-23 are calculated and reported in Tables 1 and 2. State-wise growth rates for selected occupations for the recent period are shown in Appendix Tables 1, 2, and 3. All growth rates are estimated from a semi-log function.

Table 1 Average annual rate of growth of wages for various agricultural occupations in rural India, 2014-15 to 2022-23 in per cent

| Occupation | Male | Female |

| Ploughing | 0.26 | - |

| Sowing/transplanting/weeding (STW) | 0.93*** | 0.99** |

| Harvesting/threshing/winnowing (HTW) | 0.5* | 0.3 |

| General agricultural labourers | 0.67** | 0.98** |

| Picking workers | 1.89** | 1.98*** |

| Horticulture | 1.21*** | 1.77** |

| Plant protection | (-)0.02 | - |

| Animal husbandry workers | 1.08* | 0.53 |

| Packaging labourers (agriculture) | 0.53 | 1.20*** |

Notes: ∗, ∗∗, and ∗∗∗ stand for significance level at 10, 5, and 1 per cent respectively.

Source: Labour Bureau, various years.

Table 2 Average annual rate of growth of wages for various non-agricultural occupations in rural India, 2014-15 to 2022-23 in per cent

| Occupation | Male | Female |

| Carpenter | 0.92*** | - |

| Blacksmith | 0.74** | - |

| Mason | 0.93*** | - |

| Unskilled non-agricultural labourers | 0.75*** | 0.54 |

| Construction workers | 0.48** | 1.07*** |

| Plumber | -0.1 | - |

| Electrician | 0.04 | - |

| LMV & tractor drivers | 1*** | - |

| Sweeping/cleaning workers | 1.17*** | 0.59* |

| Weavers | 0.8 | (-)0.68 |

| Beedi makers | 0.31 | 0.92* |

| Bamboo and cane-basket weavers | 0.49* | 1.35* |

| Handicraft workers | (-)1.38 | 1.21 |

Note: ∗, ∗∗, and ∗∗∗ stand for significance level at 10, 5, and 1 per cent, respectively.

Source: Labour Bureau, various years.

For the majority of occupations (19 out of 23 for men and 11 out of 16 for women), the growth in real wages was less than one per cent per annum between 2014-15 and 2022-23.

Among agricultural occupations, for men, wage growth declined sharply for all occupations (Table 1). To illustrate, average annual wage growth was 0.26 per cent for ploughing, 0.93 per cent for sowing/transplanting/weeding and 0.5 per cent for harvesting/threshing/winnowing occupations.

Wages for female workers also show a sharp deceleration. Between 2014-15 and 2022-23, wage rates grew by only 0.3 per cent and 0.99 per cent per annum for females for sowing/transplanting/weeding (STW) and harvesting/threshing/winnowing (HTW), respectively. The annual growth rate of wages for general agricultural occupations was 0.67 per cent for men and 0.98 per cent for women during the last nine years.

There are important variations across States (Appendix Table 1 and 3). States in low wage rate regions, such as Uttar Pradesh, Odisha, West Bengal, Karnataka, and Tripura, performed better than the national average. Real wages grew 1.5 to 2.5 per cent per annum depending on the operation. Andhra Pradesh performed exceptionally well. The growth of real wages in various agricultural occupations was 3-4 per cent per annum in the last 9 years. In relatively high wage States such as Tamil Nadu, Kerala, Punjab, Haryana, and Rajasthan, agricultural wages declined in real terms in the last nine years. A sharp decline in agricultural wages was also recorded in Gujarat.

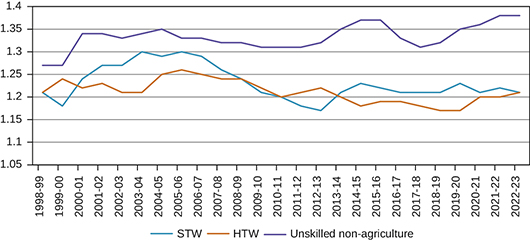

Another important finding is that male-female wage disparities have persisted in the recent period. Figure 4 shows the male-female ratio for STW and HTW over the last 25 years. The gender wage gap has increased over the last 9 years. For sowing/transplanting/weeding, the male-female wage disparity rose from 1.17 in 2012-13 to 1.22 in 2022-23. The male-female wage gap remained unchanged for harvest and post-harvest operations in the last nine years.

Figure 4 Ratio of male-to-female wage rates for sowing/transplanting/weeding (STW), harvesting/threshing/winnowing (HTW), and unskilled non-agricultural occupations, 1998-99 to 2022-23

Note: STW=sowing/transplanting/weeding, HTW=harvesting/threshing/winnowing.

Source: Labour Bureau, various years.

There was a sharp deceleration in the growth of wages for various non-agricultural occupations too (Table 2). The annual growth rate of wages for unskilled non-agricultural occupations was 0.75 per cent for men and 0.54 per cent for women during the last nine years, as compared to 7 per cent per annum between 2014-15 and 2022-23. Turning to specific non-agricultural occupations, wage growth was close to zero or very low for most occupations: 0.5 per cent per annum for packaging workers, 0.04 per cent a year for electricians. In the case of plumbers, wage growth was -0.1 per cent a year from 2014-15 to 2022-23.

For unskilled non-agricultural occupations, the gender gap in wages increased substantially from 1.32 in 2012-13 to 1.38 in 2022-23 (Figure 4).

Appendix Tables 2 and 3 present the state-wise growth in real wages from 2014-15 to 2022-23. In relatively low wage States including Bihar, Madhya Pradesh, and Odisha we find a mixed picture: while wages were stagnant for many agricultural occupations, wages for various non-agricultural occupations grew at more than 2 per cent per annum. Real wages in the construction sector increased at more than 2.5 percent per annum in Andhra Pradesh, Bihar, Madhya Pradesh, Uttar Pradesh, and West Bengal, and at more than 4 per cent in Odisha and Himachal Pradesh.

To sum up, based on WRRI data, the period from 2014-15 to 2022-23 can be characterised as a period of general stagnation in rural wages. The initial slowdown in wage growth from 2014-15 to 2018–19 can be attributed to stagnation in agricultural productivity (Himanshu 2019), successive droughts in 2014–15 and 2015–16 (Himanshu 2017 and Kundu 2019), and other macroeconomic failures. Slow growth in construction and stagnation in MGNRGES wages are additional factors that may have affected rural wages between 2014-15 and 2018-19. The more recent period (from the last quarter of 2019-20) is, of course, influenced by the pandemic. Between 2019-20 and 2021-22, real wages declined for all major agricultural and non-agricultural occupations. In 2022-23, real wages in agriculture recovered marginally, with a growth rate of wages of around one per cent. However, this was not so in the case of non-agricultural wages.

What Do the Periodic Labour Force Survey Data Show?

This section examines whether the trends in wage earnings reported in the Periodic Labour Force Survey (PLFS) of the National Sample Survey Organisation are similar to or divergent from those based on WRRI.

In 2017–18, the NSO started a new annual series of labour force surveys, known as the Periodic Labour Force Survey (PLFS), which replaced the earlier series of Employment and Unemployment Survey (EUS). One of the limitations of the labour force survey of NSO is that there are no data between 2011-12 and 2016-17. We therefore cannot cover the entire period from 2014-15 to 2022-23.

One of the drawbacks of the WRRI series is that the sample covers only one or two key respondents from a fixed set of selected centres. It is most likely that information on prevailing wage rates in selected centres is provided by village panchayat members, the VAO, or other farmers (Usami et al. 2020). The simple average of sample village figures for each state and all samples are used for the All-India estimates. Though the method is very simple and has its own limitations, WRRI series has the merit that the data are available more frequently and that they cover a longer time period than data from PLFS. On the other hand, EUS/PLFS surveys of NSO are more systematic and nationally representative sample surveys. Data on earnings are collected from workers along with information on employment based on the usual place of residence of the household. The wage earnings data cover village residents, commuters, and short-term migrants (in rural and urban areas) who are away from their usual place of residence for up to six months.

Six rounds of PLFS data (2017–18 to 2022-23) are now available and have been used for this study. Using PLFS data, we computed wage earnings from casual work in agriculture and construction tasks in rural areas for persons aged 15 years and above. The per-day wages are estimated using information on daily activity status. To calculate real wages, we use the Consumer Price Index for Agricultural Labourers (CPI-AL) at 2009-10 prices.

In Figures 1 and 2, we plot real wages for specific occupations from the two data sources for men and women. Table 3 shows the average real wage from EUS/PLFS for agriculture and construction for men and women separately, for the years 2017-18 to 2022-23. Using these data, we estimated year-on-year growth rates for the same occupations, which are reported in Table 4.

Table 3 Real wages of rural workers, by occupation and sex, 2017-18 to 2022-23 in rupees per day

| Year | Male | Female | ||

| Agricultural | Construction | Agricultural | Construction | |

| 2017-18 | 137.98 | 176.16 | 98.92 | 137.3 |

| 2018-19 | 142.33 | 182.44 | 102.61 | 136.95 |

| 2019-20 | 137.6 | 184.8 | 101.1 | 134.54 |

| 2020-21 | 145.53 | 187.4 | 107.15 | 140.22 |

| 2021-22 | 157.42 | 206.07 | 119.88 | 162.77 |

| 2022-23 | 158.08 | 205.79 | 118.92 | 157.95 |

Source: NSO, various years.

Table 4 Year on year growth of real wages of rural workers in agriculture and construction, by sex, 2017-18 to 2022-23 in per cent per annum

| Year | Male | Female | ||

| Agricultural | Construction | Agricultural | Construction | |

| 2017-18 to 2018-19 | 3.15 | 3.56 | 3.73 | -0.25 |

| 2018-19 to 2019-20 | -3.3 | 1.3 | -1.5 | -1.8 |

| 2019-20 to 2020-21 | 5.8 | 1.4 | 6.0 | 4.2 |

| 2020-21 to 2021-22 | 8.2 | 10.0 | 11.9 | 16.1 |

| 2021-22 to 2022-23 | 0.4 | -0.1 | -0.8 | -3.0 |

Source: NSO, various years.

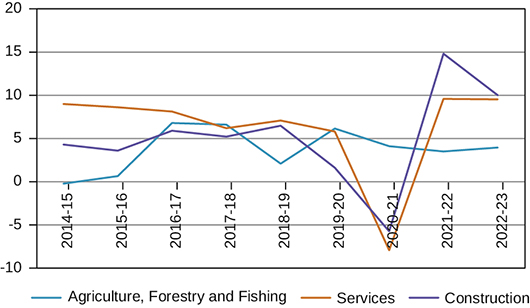

Average annual real wages from both sources of data, PLFS and WRRI, show the same trend up to 2019-20 (Figures 1 and 2).1 Although with varying magnitude, both sources show that wage rates and earnings declined in 2019-20 (which could be the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic). According to PLFS data, the wage earnings of agricultural labourers in 2019-20 declined about 3.3 per cent from the level of 2018-19, and that of construction labourers showed a nominal growth of 1 per cent for male workers. For female workers, the wage earnings in 2019-20 declined by 1.5 per cent in agriculture and by 1.8 per cent in construction. However, looking at the year-on-year growth of WRRI (Figure 3) and the quarter-on-quarter growth of PLFS (Figure 5), we see that the decline in real wages began in the first quarter of 2019 (July to October). The pandemic or lockdown, which began in March 2020 and continued until July 2020, worsened the situation. The pre-pandemic decline in real wages could have been due to seasonality or a decline in agricultural production in 2018-19. Growth of Gross Value Added of agriculture decelerated in 2018-19, and this could have affected wages (Figure 6).

Figure 5 Quarter-on-quarter changes in rural wage earnings, India, 2017-18 and 2022-23, in per cent

Source: NSO, various years

Figure 6 Growth in GVA by Sector, from 2014-15 to 2022-23

Note: Since 2013-14 is the baseline, growth estimates start in 2014-15.

Source: RBI (2023).

There is a substantial divergence between the two data series from 2020 onwards. According to WRRI data, the stagnation of real wages continued up to 2021-22 with a marginal recovery in 2022-23. On the other hand, PLFS data show a much earlier recovery; wage earnings started to recover in 2020-21 and rose substantially in 2021-22, followed by a slowdown in wage growth in 2022-23. As per PLFS, wage earnings of male agricultural labourers rose by 6 per cent in 2020-21 and 8 per cent in 2021-22.2 Wage earnings of male construction workers delayed the recovery but rose 10 per cent in 2021-22. In the case of female workers, the recovery in wages was much faster than for male workers in 2021-22. Wage earnings of female workers increased by 11.8 per cent in agriculture in 2020-21 and by 16 per cent in construction in 2021-22.

Examining changes in wages using PLFS data at the State level between 2020-21 and 2021-22, we find a rapid rise in real wages for both male and female workers in agriculture in most of the States. For men, in all large States, real wages increased significantly between 2020-21 and 2021-22. Real wages of male agricultural labourers grew more than 10 per cent in Assam, Bihar, Himachal Pradesh, Manipur, Meghalaya, Rajasthan, Uttar Pradesh, West Bengal and Tripura. Wage rates in agriculture for female labourers rose more than 20 per cent in Assam, Bihar, Maharashtra, Meghalaya, Rajasthan, Tamil Nadu, Tripura and Uttar Pradesh, while real wages declined in the relatively high-wage States of Haryana, Kerala and Punjab.

The PLFS data indicate that a sharp rise in real wages was followed by a significant slump between 2021-22 and 2022-23. At the all-India level, real wages in agriculture for men grew at 0.42 per cent in that year while it fell for women at 0.8 per cent. Bihar, Himachal Pradesh, Rajasthan, Uttar Pradesh, West Bengal, Kerala and Tamil Nadu showed an unprecedented rise in real wages in agriculture between 2020-21 and 2021-22 and a sharp decline in 2022-23.

To further cross-check the WRRI trends, we examined data from Agricultural Wages in India (AWI), a publication of the Ministry of Agriculture. Here too, we observe a stagnation in real wages in agriculture between 2017-18 and 2020-21 and low growth of less than 1.5 per cent between 2020-21 and 2021-22.

In summary, unlike WRRI, data from the PLFS suggest a K-shaped recovery in the post-pandemic period (Tables 5 and 6). In agriculture, the growth of real wages for men declined at 0.13 per cent per annum between 2017-18 and 2019-20 but increased by 4.1 per cent per annum in the post-pandemic period (2020-21 and 2022-23). For female workers, there was a substantial change in wage growth in the post-pandemic period, from 1.09 per cent per annum between 2017-18 and 2019-20 to 5.2 per cent per annum between 2020-21 and 2022-23. The growth in wages in the post-pandemic period was largely due to the sharp increase in wages in 2021-22.

Table 5 Annual growth rates of real wages in agriculture, data from PLFS and WRRI, 2017-18 to 2022-23 in per cent per annum

| Year | PLFS | WRRI | |||

| Male | Female | Ploughing (M) | STW (M) | STW (F) | |

| 2017-18 to 2019-20 | (-)0.13 | 1.1 | (-)0.24 | 0.07 | (-)0.63 |

| 2020-21 to 2022-23 | 4.1 | 5.2 | (-)0.02 | 0.65 | 0.69 |

| 2017-18 to 2022-23 | 2.96 | 4.12 | (-)0.67 | 0.13 | 0.008 |

Note: PLFS=Periodic Labour Force Survey; WRRI=Wage Rates in Rural India; All growth rates are estimated from a semi-log function.

Source: NSO and Labour Bureau, various years.

Table 6 Annual growth rates of real wages in construction as per PLFS and WRRI, 2017-18 to 2022-23 in per cent per annum

| Year | PLFS | WRRI | ||

| Male | Female | Male | Female | |

| 2017-18 to 2019-20 | 2.4 | (-)1.01 | 0.27 | 0.23 |

| 2020-21 to 2021-23 | 4.7 | 5.95 | (-)1.05 | 0.94 |

| 2017-18 to 2022-23 | 3.3 | 3.6 | (-)0.15 | 0.82 |

Note: PLFS=Periodic Labour Force Survey; WRRI=Wage Rates in Rural India; All growth rates are estimated from a semi-log function.

Source: NSO and Labour Bureau, various years.

Post-Pandemic Wage and Employment Trends

Our analysis shows clearly that there is a discrepancy between the two data sources in the timing of recovery from the impact of Covid-19. The agricultural and construction wage rates provided by WRRI show a fall in 2020-21 and 2021-22 and a slow recovery in 2022-23. The average wage earnings from PLFS show an early recovery in 2020-21, one that continued through 2021-22. Understanding this discrepancy in the post-pandemic recovery is important to assess the reliability of PLFS data. Since PLFS provides data on employment as well, we examine changes in employment patterns in agriculture and construction in order to throw some light on changes in real wages in the post-pandemic period.

Appendix Table 7 shows the change in the proportion of Usual Principal Status (UPS) and Usual Subsidiary Status (USS) workers to the total population aged 15 years and above by type of employment and broad category of industry for the last six years in rural areas. Appendix Table 7 does not provide the extent of change in the size of the workforce in each category but provides a change in the pattern of distribution of workers. The work participation rate (WPR) for males in rural areas rose gradually from 72 per cent in 2017-18 to 78 per cent in 2022-23. Major categories of employment for males were “self-employed in agriculture,” which accounted for around 30 to 32 per cent of the total population, and construction workers.

From 2017-18 to 2022-23, the female WPR increased markedly from a very low level: female WPR in rural areas increased from 23 per cent in 2017-18 to 40.7 per cent in 2022-23. The rise in female WPR, particularly from 2019-20, in rural areas stems from an increase in women engaged in self-employment in agriculture.

There are three points on employment during the lockdown and post-lockdown period that emerge from the Periodic Labour Force Survey (PLFS) that need to be examined in detail.

First, the nationwide lockdown, which was introduced in March 2020 and continued till June 2020, severely affected the employment and earnings of rural casual workers (Kesar et al. 2020; Estupinan and Sharma 2020, and Patra et al. 2021). The share of male construction labourers fell from 9.4 per cent in 2018-19 to 9.3 per cent in 2019-20, while there was a slight increase in male agricultural labourers, from 8.4 per cent in 2018-19 to 8.9 per cent in 2019-20.

The lockdown affected the economy as shown by data on Gross Value Added in Figure 6. The GVA in service and construction industries fell 8 per cent and 6 per cent respectively in 2020-21, which affected employment as well as wage earnings in these sectors. Almost all major States except Andhra Pradesh and Gujarat showed a significant decline in Gross State Value Added (GSVA) of the construction industry (Appendix Table 6). Because of a difference between the agricultural year (July to June next year) and the financial year (April to March), the impact of the lockdown was reflected in the wage and employment data of 2019-20, but affected the GVA of 2020-21.

Both WRRI wage rates and PLFS wage earnings show the impact of the Covid-19 lockdown on the rural labour market in 2019-20. WRRI data shows that real wages declined by 2 per cent, while real wages in agriculture declined by 3 per cent in PLFS data. In the case of male construction work, WRRI data shows a decline in real wages, while PLFS showed less than one per cent growth in 2019-20.

Secondly, while wage rates and earnings followed a similar pattern at the time of lockdown, a completely different pattern appeared after the first lockdown in 2020. While wage earnings and employment of agricultural and construction labourers estimated from the PLFS showed a quick recovery post-lockdown, wage rates remained depressed, according to WRRI data. Is this due to the changes in the pattern of employment in the post-pandemic period?

PLFS data on employment shows a shift from agriculture to construction for male workers in the last three years. Casual labour in the construction industry expanded rapidly for rural male workers over the last three years (2020-21 to 2022-23). Construction workers as a share of total population increased by 0.6 percentage points between 2020-21 to 2021-22 (9.7 per cent in 2020-21 and 10.3 per cent in 2021-22), but rose sharply, by 2 percentage points, in 2022-23. The GVA of the construction industry recovered quickly from the sudden drop and grew at 15 per cent in 2021-22 and 10 per cent in 2022-23.

Among rural males, agricultural workers as a share of total population fell sharply -- from 8.2 per cent in 2020-21 to 6.2 per cent in 2022-23 (Appendix Table 7). In absolute terms, the total number of agricultural labourers declined from 23.9 million in 2017-18 to 19.7 million in 2022-23 (Appendix Table 11). It is difficult to imagine that the share of male agricultural labourers in the population of Uttar Pradesh was just 2.3 per cent, while the share of construction labourers was 13 per cent in 2022-23 (Appendix Tables 8 and 10).

It appears that a majority of new workers entered the construction industry and that workers also shifted from agriculture into the construction industry. The shift from the agricultural sector to the construction sector is arguably due to higher wage earnings in the latter. Data show, however, that the ratio of agricultural wages to construction wages remained constant, at around 76 to 78 per cent, throughout the period. This suggests that the rapid expansion of construction labour may have led to an increase in agricultural wage earnings too.

According to PLFS data, the wage earnings of male agricultural labourers grew 5.7 per cent in 2020-21 and 8.1 per cent in 2021-22, while the wage earnings of construction labourers recorded a very slow growth in 2020-21 and then went up 10 per cent in 2021-22 (Table 4). WRRI data show that there was no recovery in real wages in rural areas in the post-pandemic period: real wage rates for various agricultural occupations either declined or grew at less than 1 per cent. For example, ploughing wages declined by 1.5 per cent in 2020-21 and 0.63 per cent in 2021-22. For male workers in sowing/transplanting/weeding operations, real wages increased by 1.12 per cent in 2020-21 but declined by 0.12 per cent in 2021-22. For construction work, real wage rates increased marginally in 2020-21 and declined by 1 per cent in 2021-22.

It is surprising that while employment and GVA in construction grew rapidly in 2022-23, wage earnings of agriculture workers and construction workers did not grow at all. Real wages in agriculture in both WRRI and PLFS data show a growth of less than one per cent in 2022-23, while real wages declined for the construction sector in both data series.

The third point which requires closer examination relates to women’s employment. According to Arora (2023), the recent rise in WPR and decline in the unemployment rate should be examined from the point of view of “which type of work is created and whether income is rising.” Women’s work participation in “self-employed in agriculture” increased rapidly. Appendix Table 7 shows that the share of the self-employed in agriculture in the total population rose from 11.2 per cent in 2017-18 to 17.2 per cent in 2019-20 and further to 24.3 per cent in 2022-23. The share of casual agricultural labourers also increased from 5.9 per cent in 2017-18 to 6.5 per cent in 2022-23 (Appendix Table 9). All other categories of employment grew at a very slow pace. We argue that the rise in WPR may reflect women not in the work force shifting to self-employment in agriculture.3

Conclusion

Using Wage Rates in Rural India (WRRI) series of the Labour Bureau, this paper revises and updates our previous work (Das and Usami 2017) and extends the coverage of the data to 2022-23. The main finding from our analysis of real wages from WRRI is of a stagnation in real wages in the last nine years. The growth of rural wages for the majority of rural occupations was less than one per cent a year during this near-decade. This is in sharp contrast to the previous period (2006-07 to 2014-15), during which real wages grew by more than 6 per cent per annum.

WRRI data shows that the stagnation in real wages began in 2014-15 and continued until 2018-19. The Covid-19 pandemic and lockdown worsened the situation, and real wages declined drastically in 2019-20 and 2020-21. In the post-pandemic period, real wages did not show much sign of recovery.

Using data from the Periodic Labour Force Survey of NSO from 2017-18 to 2022-23, we find a pattern of growth of real wages that is divergent from the pattern that emerges from WRRI, especially in the post-pandemic period. According to PLFS, the recovery of real wages began in 2020-21. The rise in real wages, both in agriculture and construction, was notable from 2020-21 to 2021-22. Real wages grew annually at more than 8 per cent for male agricultural workers and 11 per cent for female agricultural workers. In construction too, real wages recovered by 10 per cent for the male workers in the same period. The momentum of the growth did not continue in 2022-23.

The reasons for (a) these sudden changes in the PLFS data and (b) the divergence of PLFS growth patterns from the major source of data on rural wages, WRRI, in the post-pandemic period, need further examination. A preliminary analysis of employment data of PLFS and GSVA suggests that for men, the sharp rise in real wages in rural areas in 2021-22 may be an outcome of changes in employment structure, particularly in the construction industry. In 2022-23, though employment in the construction sector increased significantly, real wages did not rise at all. For women, understanding the rise in work participation rates alongside wage growth also needs further investigation. We need to be cautious in using the PLFS wage series until we understand these discrepancies.

Acknowledgements: We thank Madhura Swaminathan and an anonymous referee for their suggestions on this paper.

Notes

1 We have also estimated the real earnings of agriculture and construction from the Employment and Unemployment survey of 2007-08, 2009-10 and 2011-12 and compared them with WRRI data (Figures 1 and 2).

2 It is interesting that wages for casual workers in urban areas also showed a notable rise in 2021-22.

3 As discussed by Swaminathan (2020), many women report themselves as out of the work force when suitable employment is not available.

References

| Arora, Akshit (2023), “Making Sense of Recent Developments in the Indian Labour Market,” The India Forum, Oct. 17, available at https://www.theindiaforum.in/forum/making-sense-recent-developments-indian-labour-market, viewed on November 20, 2023. | |

| Azam, M. (2012), “The Impact of Indian Job Guarantee Scheme on Labour Market Outcomes: Evidence From a Natural Experiment,” IZA Discussion Paper 6548, Institute for the Study of Labour, Bonn. | |

| Berg, Erlend, Bhattacharyya, Sambit, Durgam, Rajasekhar, and Ramachandra, Manjula (2012), “Can Rural Public Works Affect Agricultural Wages? Evidence from India,” CSAE Working Paper WPS/2012–05, Centre for the Study of African Economies, Department of Economics, University of Oxford, Oxford. | |

| Bhalla, Surjit (2023), “Contrary to Claims, Rural Wages Have Risen Rapidly,” Indian Express, April 25, available at https://indianexpress.com/article/opinion/columns/surjit-bhalla-writes-contrary-to-claims-rural-wages-have-risen-rapidly-8573897/, viewed on October 15, 2023. | |

| Chandrasekhar, C. P., and Ghosh, Jayati (2011), “Public Work and Wages in Rural India,” https://www.macroscan.org/fet/jan11/fet110111Public_Works.htm, viewed on October 30, 2023. | |

| Das, Arindam, and Usami, Yoshifumi (2017), “Wage Rates in Rural India, 1998–99 to 2016–17,” Review of Agrarian Studies, vol. 7, no. 2, pp. 4-18, available at http://www.ras.org.in/wage_rates_in_rural_india_1998. | |

| Drèze, Jean (2023a), “Wages Are The Worry, Not Just Unemployment,” Indian Express, Apr. 13, available at https://indianexpress.com/article/opinion/columns/jean-dreze-writes-wages-are-the-worry-not-just-unemployment-8553226/, viewed on April 14, 2023. | |

| Drèze, Jean (2023b), “Distress is There to See,” Indian Express, May 25, available at https://indianexpress.com/article/opinion/columns/since-2014-the-poorest-communities-are-earning-less-8625367/, viewed on May 25, 2023. | |

| Estupinan, Xavier, and Sharma, Mohit (2020), “Job and Wage Losses in Informal Sector Due to the COVID-19 Lockdown Measures in India,” Labour and Development, vol. 27, no.1, pp. 1-16, available at http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3680379, viewed on December 27, 2023. | |

| Gulati, Ashok, Jain, Surbhi, and Satija, Nidhi (2013), “Rising Farm Wages in India: The ‘Pull’ and ‘Push’ Factors,” Discussion Paper No. 5, Commission for Agricultural Costs and Prices, Department of Agriculture and Cooperation, Ministry of Agriculture, Government of India, New Delhi. | |

| Himanshu, and Kundu, Sujata (2016), “Rural Wages in India: Recent Trends and Determinants,” Indian Journal of Labour Economics, vol. 59, no. 2, pp. 217–44. | |

| Himanshu (2017), “Growth, Structural Change and Wages in India: Recent Trends,” Indian Journal of Labour Economics, vol. 60, no. 3, pp. 309–31. | |

| Himanshu (2019), “India’s Farm Crisis: Decades Old and with Deep Roots”, Ideas for India, Apr. 12, https://www.ideasforindia.in/topics/agriculture/indias-farm-crisis-decades-old-and-with-deep-roots.html, viewed on December 21, 2023. | |

| Jose, A. V. (2013), ‘‘Changes in Wages and Earnings of Rural Labourers,” Economic and Political Weekly, vol. XLVIII, no. 26/27, pp. 107–14. | |

| Kesar, Surbhi, Abraham, Rosa, Lahoti, Rahul, Nath, Paaritosh, and Basole, Amit (2020), “Pandemic, Informality, and Vulnerability: Impact of COVID-19 on Livelihoods in India,” Working Paper #27, Centre for Sustainable Employment, Azim Premji University, Bengaluru. | |

| Kundu, Sujata (2019), “Rural Wage Dynamics in India: What Role does Inflation Play?” RBI Occasional Papers, vol. 40, no.1, pp. 51-84 Mumbai, available at https://www.rbi.org.in/Scripts/PublicationsView.aspx?id=18970, viewed on Dec. 21, 2023. | |

| Labour Bureau, Wage Rates in Rural India, Ministry of Labour and Employment, Government of India, Shimla, various years. | |

| Patra, Subhajit, Mahato, Rakesh Kumar, and Das, Arindam (2021), “Impact of Covid-19 on Employment and Wages in Rural India, March-September 2020,” Review of Agrarian Studies, vol. 11, no. 2, pp. 143-52, available at https://ras.org.in/index.php?Article=impact_of_covid_19_on_employment_and_wages_in_rural_india_march_september_2020. | |

| Menon, Rahul (2023), “Have earnings grown post-pandemic?” The Hindu, October 22, available at https://www.thehindu.com/business/Economy/have-earnings-grown-post-pandemic/article67450614.ece, viewed on Dec 18, 2023. | |

| National Statistical Office (NSO), Periodic Labour Force Survey, New Delhi, various years. | |

| Reserve Bank of India (RBI) (2023), Handbook of Statistics on Indian Economy, Reserve Bank of India, Mumbai | |

| Review of Agrarian Studies (RAS) (2019), “Stagnation in Rural Wage Rates,” Editorial in Review of Agrarian Studies, vol. 9, no. 1, available at https://ras.org.in/index.php?Article=stagnation_in_rural_wage_rates. | |

| Swaminathan, Madhura (2020), “Measuring Women’s Work with Time Use Data: An Illustration from Two Villages from Karnataka,” in Swaminathan, M., Nagbhushan, S., and Ramachandran, V. K. (eds.), Women and Work in Rural India, Tulika Books, New Delhi, pp. 19-39. | |

| Usami, Yoshifumi (2011), “A Note on Recent Trends in Wage Rates in Rural India,” Review of Agrarian Studies, vol. 1, no. 1, available at https://ras.org.in/index.php?Article=methodology_of_data_collection_unsuited_to_changing_rural_reality | |

| Usami, Yoshifumi, Das, Arindam, and Swaminathan, Madhura (2020), “Methodology of Data Collection Unsuited to Changing Rural Reality: A Study of Agricultural Wage Data in India,” Review of Agrarian Studies, vol. 10, no. 2, pp. 48-74, available at http://ras.org.in/ |

Appendix Tables

Appendix Table 1 Average annual rate of growth of wage rates for major agricultural occupations in rural India, by State, 2014-15 to 2022-23 in per cent

| State | Ploughing (M) | STW (M) | STW (F) | HTW (M) | HTW (F) |

| Andhra Pradesh | 2.41*** | 3.83*** | 4.37*** | 3.22*** | 3.45** |

| Karnataka | 0.76 | 2.16** | 2.14** | 1.26 | 2.02** |

| Kerala | -2.08*** | -0.25 | -0.76* | -0.48 | -0.63 |

| Tamil Nadu | -1.27 | 0.23 | -0.26 | -0.49 | -0.97 |

| Haryana | -2.08*** | -1.37 | -1.44** | -1.27** | -2.45*** |

| Himachal Pradesh | -1.04 | -0.21*** | 0.61 | ||

| Jammu & Kashmir | 1.03 | 0.06 | 0.3 | ||

| Punjab | -1.72*** | 0.06 | - | -0.01 | - |

| Rajasthan | -1.2 | -1.71*** | 0.03 | -1.33 | 0.05 |

| Gujarat | -0.36 | 0.15 | 0.4 | 0.57 | 0.5 |

| Maharashtra | 0.13 | 1.25** | 2.36*** | 1.33 | 2.21** |

| Madhya Pradesh | 1.16 | 1.19 | 0.47 | 0.55 | -0.07 |

| Uttar Pradesh | 1.7* | 2.96*** | 2.92** | 2.05** | 2.51** |

| Bihar | 1.62* | 1.75* | 1.26 | 1.26* | 0.32 |

| Odisha | 1.13 | 2.16*** | 2.41* | 1.39* | 1.43 |

| West Bengal | 0.31 | 2.12*** | 1.25** | 1.44* | 1.01 |

| Assam | 1.89*** | 1.01 | 1.07 | 0.76 | 0.55 |

| Manipur | -1.52*** | -1.65 | -0.9* | -2.83*** | -1.59*** |

| Meghalaya | -1.02 | 0.83 | -0.99 | -0.32 | -1.53 |

| Tripura | 1.9 | 1.9 | - | 2.07 | - |

| India | 0.26 | 0.93** | 0.99* | 0.5 | 0.3 |

Notes: ∗, ∗∗, and ∗∗∗ stand for significance level at 10, 5, and 1 per cent respectively. States are arranged by regions – south, north, west, east, and north-east. STW=sowing/transplanting/weeding, HTW=harvesting/threshing/winnowing.

Source: Labour Bureau, various years.

Appendix Table 2 Average annual rate of growth of wage rates for major non-agricultural occupations in rural India, by State, 2014-15 to 2022-23 in per cent

| State | Carpenter (male) | Blacksmith (male) | Mason (male) | Construction (male) | Construction (female) |

| Andhra Pradesh | 3.17*** | 2.17*** | 2.99*** | 3.18*** | 3.04*** |

| Karnataka | 0.73** | -0.69 | 2.89*** | 0.4 | 0.89 |

| Kerala | 1.28*** | -0.55 | 0.85* | -1.31** | |

| Tamil Nadu | -0.5 | -0.7 | -0.56 | -1.3 | -1.3*** |

| Haryana | -1.5** | -1.98** | -2.16*** | -3.17*** | |

| Himachal Pradesh | 2.84*** | 3.82*** | 2.73*** | 4.66*** | |

| Jammu & Kashmir | 1.12*** | 0.54 | 1.19** | -0.73** | |

| Punjab | -1.93*** | -2.91*** | -2.12*** | -1.96*** | -1.1** |

| Rajasthan | -1.73*** | -1.1 | -1.78** | -2.3*** | -2.53*** |

| Gujarat | -1.24** | -1.23* | -1.64*** | 0.29 | 1.79*** |

| Maharashtra | -1.25*** | -0.74* | -0.25 | -0.77* | -0.7 |

| Madhya Pradesh | 2.44*** | 2.79*** | 2.16** | 2.5** | 1.66* |

| Uttar Pradesh | 2*** | 1.87** | 1.54** | 2.65*** | 2.98*** |

| Bihar | 3.13*** | 2.72*** | 2.74** | 2.82*** | 2.97*** |

| Odisha | 2.97*** | 3.3*** | 2.66*** | 4.09*** | 3.97*** |

| West Bengal | 2.15*** | 1.47*** | 1.76** | 2.38** | 1.24* |

| Assam | 1.01*** | 1.27*** | 0.67** | 1.55** | 1.38** |

| Manipur | 0.23 | 1.4* | 0.26 | 0.12 | |

| Meghalaya | 0.5 | 1.86** | 1.35 | 2.45* | |

| Tripura | -1.04 | -0.26 | -2.53 | 0.23 | |

| India | 0.92*** | 0.74** | 0.93*** | 0.48** | 1.07*** |

Note: Same as in Appendix Table 1.

Source: Labour Bureau, various years.

Appendix Table 3 Average annual rate of growth of wage rates for major unskilled occupations in rural India, by State, 2014-15 to 2022-23 in per cent

| State | General agricultural labour (male) | General agricultural labour (female) | Unskilled labour (male) | Unskilled labour (female) |

| Andhra Pradesh | 2.02** | 3.29** | 1.93*** | 2.15*** |

| Karnataka | 2.2** | 2.08** | 1.06*** | 1.58** |

| Kerala | (-)1*** | (-)0.97* | -0.61 | |

| Tamil Nadu | (-)2.39*** | 0.13 | (-)1.3** | (-)0.91* |

| Haryana | (-)1.81** | (-)1.9** | ||

| Himachal Pradesh | 1.73** | 1.76* | 4.31*** | |

| Jammu & Kashmir | 0.06 | -0.42 | ||

| Punjab | (-)0.74* | (-)1.74*** | ||

| Rajasthan | -0.55 | 0.3 | (-)2.08*** | (-)2.87** |

| Gujarat | (-)0.29 | (-)0.02 | 0.6 | -0.85 |

| Maharashtra | 0.99 | 1.27* | -0.69 | 0.2 |

| Madhya Pradesh | 1.28 | 0.61 | 2.3*** | 3.72** |

| Uttar Pradesh | 2.42** | 2.38** | 2.65*** | 1.74** |

| Bihar | 1.71** | 3.25* | 2.82*** | 1.46* |

| Odisha | 1.52* | 0.99 | 4.52*** | 2.97** |

| West Bengal | 1.14** | 2.11** | 2.4*** | -0.29 |

| Assam | 1.94* | (-)0.22 | 2.3*** | 1.8* |

| Manipur | ||||

| Meghalaya | 1.7 | (-)0.2 | 0.92 | |

| Tripura | 2.03 | 0.05 | ||

| India | 0.67* | 0.98* | 0.75*** | 0.54 |

Note: Same as in Appendix Table 1.

Source: Labour Bureau, various years.

Appendix Table 4 Annual growth rates of real wages in agriculture, male, by sub-period, 2017-18 to 2022-23 in per cent

| State | 2017-18 to 2019-20 | 2020-21 to 2021-22 | 2021-22 to 2022-23 | 2020-21 to 2022-23 | 2017-18 to 2022-23 |

| Andhra Pradesh | 0.53 | 3.93 | 4.76 | 4.25 | 3.73 |

| Karnataka | -0.38 | 5.9 | 6.63 | 6.08 | 3.9 |

| Kerala | 9.48 | 7.32 | -9.45 | -1.43 | 3.55 |

| Tamil Nadu | -0.55 | 6.09 | 3.57 | 4.71 | 2.04 |

| Haryana | 3.54 | 2.39 | -6.36 | -2.11 | 1.09 |

| Punjab | -2.12 | 3.95 | 1.54 | 2.7 | 1.13 |

| Himachal Pradesh | -3.9 | 30.1 | -12.06 | 6.73 | 1.76 |

| J&K | 8.55 | -10.48 | -4.83 | -8.01 | -1.32 |

| Rajasthan | 0.06 | 19.21 | -13.64 | 1.45 | 0.35 |

| Gujarat | -1.33 | 7.22 | 4.91 | 5.88 | 0.47 |

| Maharashtra | -2.83 | 8.37 | 6.6 | 7.21 | 2.86 |

| Madhya Pradesh | 0.58 | 4.56 | 4.44 | 4.4 | 1.64 |

| Uttar Pradesh | 4.45 | 17.55 | -7.62 | 4.12 | 6.15 |

| Assam | 3.9 | 18.7 | 3.92 | 10.5 | 3.16 |

| Bihar | -2.76 | 15.45 | -6.07 | 4.05 | 1.39 |

| Orissa | 7.4 | 4.06 | 2.66 | 3.3 | 4.45 |

| West Bengal | 4.29 | 18.24 | -4.97 | 5.83 | 4.01 |

| Manipur | -0.59 | 11.03 | 1.66 | 6.05 | 8.66 |

| Meghalaya | -14.68 | 14.57 | 10.6 | 11.84 | -2.05 |

| Tripura | -4.64 | 29.22 | -5.6 | 9.93 | 3.06 |

| India | -0.15 | 8.18 | 0.44 | 4.15 | 2.97 |

Note: States are grouped geographically (southern, north-western, western, northern, north-eastern).

Source: NSO, various years.

Appendix Table 5 Annual growth rates of real wages in agriculture, female, by sub-period, 2017-18 to 2022-23 in per cent

| State | 2017-18 to 2019-20 | 2020-21 to 2021-22 | 2021-22 to 2022-23 | 2020-21 to 2022-23 | 2017-18 to 2022-23 |

| Andhra Pradesh | 0.71 | 9.06 | 1.36 | 5.01 | 4.7 |

| Karnataka | 3.51 | 7.55 | 12.21 | 9.4 | 6.15 |

| Kerala | 5.99 | -0.34 | -2.14 | -1.25 | 0.53 |

| Tamil Nadu | -4.35 | 23.61 | -3.55 | 8.79 | 3.21 |

| Haryana | 6.38 | -2.49 | 2.37 | -0.09 | 4.31 |

| Punjab | 3.58 | -2.01 | 0.86 | -0.59 | 1.22 |

| Himachal Pradesh | 18.06 | 14.92 | -5.9 | 3.91 | 8.68 |

| Rajasthan | -15.6 | 33.25 | -1.54 | 13.58 | 7.25 |

| Gujarat | -1.97 | -4.81 | 2.47 | -1.24 | -0.71 |

| Maharashtra | -0.83 | 20.18 | -4.01 | 7.15 | 6.23 |

| Madhya Pradesh | 2.81 | 5.93 | 3.91 | 4.8 | 1.42 |

| Uttar Pradesh | 0.96 | 23.32 | -14.92 | 2.4 | 2.22 |

| Assam | 6.91 | 25.79 | -7.19 | 7.74 | 5.37 |

| Bihar | 14.18 | 21.08 | -5.28 | 6.85 | 8.44 |

| Orissa | 10.21 | 10.78 | -5.47 | 2.3 | 3.87 |

| West Bengal | 11.86 | 8.14 | -4.96 | 1.37 | 2.73 |

| Manipur | 12.01 | 7.27 | -0.21 | 3.4 | 12.11 |

| Meghalaya | -19.9 | 36.55 | 0.07 | 15.61 | -1.41 |

| Tripura | -1.71 | 35.68 | -4.96 | 12.71 | 3.82 |

| India | 1.1 | 11.95 | -0.83 | 5.23 | 4.13 |

Note: States are grouped geographically (southern, north-western, western, northern, north-eastern).

Source: NSO, various years.

Appendix Table 6 Year-on-year Gross State Value Added (GSVA) in construction sector

| State | 2018-19 | 2019-20 | 2020-21 | 2021-22 | 2022-23 |

| Andhra Pradesh | 4.4 | -9.4 | 6 | 13.2 | 4.7 |

| Karnataka | 8.3 | -0.5 | -8.4 | 7.9 | 6.6 |

| Kerala | 4.1 | 3.7 | -5.6 | 6.4 | NA |

| Tamil Nadu | 5.7 | 3.6 | 1.2 | 8 | 7.5 |

| Punjab | 7.4 | 3.5 | 0.8 | 8.3 | 7.7 |

| Haryana | 9 | 1.4 | -9.2 | 12.7 | 7.8 |

| Himachal Pradesh | 3 | -0.1 | -5.2 | -0.5 | 9.5 |

| Rajasthan | 5.1 | 5.1 | -5.6 | 12.8 | 9.1 |

| Gujarat | 12.3 | 1.1 | 23.3 | 8 | NA |

| Maharashtra | 3.8 | 0.4 | -2.5 | 1.3 | NA |

| Madhya Pradesh | 15.3 | -5.6 | -6.8 | 18.4 | 5.9 |

| Uttar Pradesh | 10.9 | 4.1 | -7.2 | 14.8 | 15.3 |

| Assam | -1.8 | 13.2 | 0.9 | 8.6 | NA |

| Bihar | 9.2 | 1 | -7 | 12.2 | NA |

| Odisha | 4 | 0.2 | -9 | 19 | 9.5 |

| West Bengal | 6.1 | 3.2 | -7.9 | 30.2 | 10.4 |

Notes: Base year 2017-18. NA=not available, Since 2017-18 is the baseline, Y-o-Y changes start in 2018-19.

Source: RBI (2023).

Appendix Table 7 Proportion of workers to the population (WPR), by employment status and the broad category of industry, in rural areas in per cent

| Employment status | Industry | Male | Female | ||||||||||

| 2017-18 | 2018-19 | 2019-20 | 2020-21 | 2021-22 | 2022-23 | 2017-18 | 2018-19 | 2019-20 | 2020-21 | 2021-22 | 2022-23 | ||

| Self-employment | Agriculture | 30.5 | 29.6 | 31.5 | 31.6 | 30.8 | 31.7 | 11.2 | 12.3 | 17.2 | 19.7 | 20.6 | 24.3 |

| Manufacturing | 2.1 | 2 | 2.2 | 2.5 | 2.2 | 2.5 | 1.4 | 1.8 | 1.8 | 2 | 2.3 | 2.8 | |

| Construction | 1 | 1.1 | 1.2 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Services | 8 | 8.7 | 8.5 | 9.2 | 9.6 | 9.9 | 1 | 1.1 | 1.2 | 1.4 | 1.4 | 1.9 | |

| Regular wage workers | Agriculture | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.7 | 0.6 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.2 |

| Manufacturing | 2.5 | 2.7 | 2.7 | 2.8 | 3.2 | 3.5 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.4 | |

| Construction | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Services | 6.7 | 6.8 | 6.6 | 6.5 | 7.1 | 6.9 | 2 | 2.3 | 2.3 | 2.5 | 2.3 | 2.6 | |

| Public work | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.6 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 1.1 | 1.1 | 1 | |

| Casual Labourer | Agriculture | 8.6 | 8.4 | 8.9 | 8.2 | 7.3 | 6.2 | 5.9 | 5.6 | 6.7 | 6.9 | 6.4 | 6.5 |

| Manufacturing | 1.5 | 1.2 | 1.1 | 1.2 | 1.1 | 1.1 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.2 | |

| Construction | 8.7 | 9.4 | 9.3 | 9.7 | 10.3 | 12.5 | 0.6 | 0.7 | 0.9 | 1.1 | 0.8 | 0.8 | |

| Services | 1.1 | 1.2 | 1 | 0.9 | 1.1 | 1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | |

| WPR | 72 | 72.2 | 74.4 | 75.1 | 75.3 | 78 | 23.7 | 25.5 | 32.2 | 35.8 | 35.8 | 40.7 | |

Note: Workers include both usual principal and subsidiary activity status workers.

Source: NSO.

Appendix Table 8 Proportion of casual workers in agriculture to the population, males, in rural areas, age 15 years and above in per cent

| State | 2017-18 | 2018-19 | 2019-20 | 2020-21 | 2021-22 | 2022-23 |

| Andhra Pradesh | 19.2 | 15 | 20.2 | 20.6 | 14.8 | 12.5 |

| Karnataka | 13.3 | 12.5 | 11.6 | 14.5 | 12.2 | 9.6 |

| Kerala | 7.4 | 7.7 | 6.5 | 7.2 | 4.7 | 6.7 |

| Tamil Nadu | 12.3 | 9.8 | 12.1 | 12.6 | 11.5 | 9.1 |

| Punjab | 6 | 8.8 | 8 | 5.8 | 4.5 | 5.4 |

| Haryana | 3.9 | 5.9 | 3.2 | 2.9 | 2.9 | 2.2 |

| Himachal Pradesh | 0.9 | 1.1 | 1.1 | 1.4 | 1.2 | 0.9 |

| Rajasthan | 2.2 | 1.8 | 3 | 2.6 | 2.1 | 2 |

| Gujarat | 9.7 | 11.2 | 13.8 | 11.6 | 8.1 | 10 |

| Maharashtra | 15.1 | 14.2 | 16.8 | 15 | 16.4 | 14.5 |

| Madhya Pradesh | 11.7 | 12.8 | 11.1 | 11.5 | 9 | 7.9 |

| Uttar Pradesh | 4.5 | 3.9 | 4 | 4.3 | 3.2 | 2.3 |

| Assam | 4.6 | 2.3 | 4 | 2.6 | 3 | 2.9 |

| Bihar | 7 | 9.8 | 8.2 | 6.9 | 6.9 | 6.1 |

| Odisha | 5.5 | 3.8 | 3.9 | 2.2 | 2.6 | 2.3 |

| West Bengal | 16.1 | 16 | 15.5 | 13.4 | 13.1 | 9.7 |

| All India | 8.6 | 8.4 | 8.9 | 8.2 | 7.3 | 6.2 |

Note: Workers include both usual principal and subsidiary activity status workers.

Source: NSO.

Appendix Table 9 Proportion of casual workers in agriculture to the population, females, in rural areas, age 15 years and above in per cent

| State | 2017-18 | 2018-19 | 2019-20 | 2020-21 | 2021-22 | 2022-23 |

| Andhra Pradesh | 21.3 | 19.9 | 19.4 | 24.5 | 18.6 | 18.9 |

| Karnataka | 11.3 | 11.2 | 14.1 | 15 | 13.1 | 13.4 |

| Kerala | 1.9 | 2.2 | 2.3 | 0 | 1.6 | 1.5 |

| Tamil Nadu | 10.3 | 9.4 | 12.3 | 12.7 | 11.4 | 10.9 |

| Punjab | 1.7 | 1.9 | 1.9 | 3.8 | 2.6 | 2.8 |

| Haryana | 3.7 | 2.7 | 3.2 | 3.3 | 3.9 | 4.6 |

| Himachal Pradesh | 0 | 0.2 | 0.6 | 0.2 | 0.7 | 0.2 |

| Rajasthan | 1 | 0.7 | 1.7 | 2.1 | 1.2 | 2.4 |

| Gujarat | 4.8 | 5.5 | 9.1 | 9.1 | 6.6 | 9.2 |

| Maharashtra | 14.8 | 14.6 | 18.7 | 0 | 17.9 | 16.4 |

| Madhya Pradesh | 9.5 | 8.4 | 9.1 | 10.4 | 8.7 | 9.8 |

| Uttar Pradesh | 1.3 | 1.5 | 1.2 | 1.3 | 1.6 | 1.9 |

| Assam | 1.8 | 1.2 | 1.7 | 1.1 | 2.2 | 0.9 |

| Bihar | 1.3 | 1.7 | 3.6 | 2.6 | 3.2 | 4.8 |

| Odisha | 4.3 | 3.6 | 4.3 | 3.5 | 4.5 | 4.2 |

| West Bengal | 5.5 | 4.2 | 4.5 | 6.1 | 5.9 | 5.7 |

| All India | 5.9 | 5.6 | 6.7 | 6.9 | 6.4 | 6.5 |

Note: Workers include both usual principal and subsidiary activity status workers.

Source: NSO.

Appendix Table 10 Proportion of casual workers in construction to the population, males, in rural areas, age 15 years and above in per cent

| State | 2017-18 | 2018-19 | 2019-20 | 2020-21 | 2021-22 | 2022-23 |

| Andhra Pradesh | 8.1 | 8.2 | 6.9 | 7 | 7.9 | 9 |

| Karnataka | 5.1 | 7.1 | 5.8 | 6.7 | 7.2 | 7.4 |

| Kerala | 11.6 | 12.1 | 12.8 | 13.3 | 13.9 | 13.3 |

| Tamil Nadu | 9.9 | 10.3 | 11.7 | 12.6 | 12.3 | 12.6 |

| Punjab | 9.7 | 10.6 | 11.6 | 16 | 14.3 | 12 |

| Haryana | 9.4 | 10.4 | 10.2 | 10.7 | 10.3 | 10 |

| Himachal Pradesh | 10.4 | 10.8 | 12.6 | 11.3 | 11.2 | 9.5 |

| Rajasthan | 8.8 | 8.9 | 8.2 | 7 | 9.1 | 8.9 |

| Gujarat | 4.2 | 3.5 | 3.8 | 4.6 | 4.5 | 7 |

| Maharashtra | 3.4 | 4.5 | 3.9 | 4.1 | 4.5 | 4.5 |

| Madhya Pradesh | 9.7 | 11.2 | 9.4 | 8.1 | 10.5 | 10.1 |

| Uttar Pradesh | 10.9 | 10.9 | 11.5 | 10.2 | 11.6 | 13 |

| Assam | 6.4 | 8.1 | 7.7 | 10.7 | 10.3 | 30.1 |

| Bihar | 8.7 | 10.4 | 12.9 | 12.3 | 12.8 | 14.4 |

| Odisha | 12 | 14.9 | 14.3 | 17.2 | 15.1 | 16.8 |

| West Bengal | 9.8 | 9.9 | 9.9 | 10.8 | 10.8 | 13.1 |

| All India | 8.7 | 9.4 | 9.3 | 9.7 | 10.3 | 12.5 |

Note: Workers include both usual principal and subsidiary activity status workers.

Source: NSO.

Appendix Table 11 Estimated number (000) of casual agricultural labourers in rural areas, from 2017-18 to 2022-23

| Year | Male | Female |

| 2017-18 | 23,944 | 15,976 |

| 2018-19 | 22,981 | 15,396 |

| 2019-20 | 25,524 | 19,142 |

| 2020-21 | 23,712 | 19,846 |

| 2021-22 | 22,281 | 19,328 |

| 2022-23 | 19,725 | 20,661 |

Note: Workers include both usual principal and subsidiary activity status workers.

Source: NSO.

Date of submission of manuscript: October 20, 2023

Date of acceptance for publication: December 26, 2023